Congleton Archaeological Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roadside Hedge and Tree Maintenance Programme

Roadside hedge and tree maintenance programme The programme for Cheshire East Higways’ hedge cutting in 2013/14 is shown below. It is due to commence in mid-October and scheduled for approximately 4 weeks. Two teams operating at the same time will cover the 30km and 162 sites Team 1 Team 2 Congleton LAP Knutsford LAP Crewe LAP Wilmslow LAP Nantwich LAP Poynton LAP Macclesfield LAP within the Cheshire East area in the following order:- LAP = Local Area Partnership. A map can be viewed: http://www.cheshireeast.gov.uk/PDF/laps-wards-a3[2].pdf The 2013 Hedge Inventory is as follows: 1 2013 HEDGE INVENTORY CHESHIRE EAST HIGHWAYS LAP 2 Peel Lne/Peel drive rhs of jct. Astbury Congleton 3 Alexandra Rd./Booth Lane Middlewich each side link FW Congleton 4 Astbury St./Banky Fields P.R.W Congleton Congleton 5 Audley Rd./Barley Croft Alsager between 81/83 Congleton 6 Bradwall Rd./Twemlow Avenue Sandbach link FW Congleton 7 Centurian Way Verges Middlewich Congleton 8 Chatsworth Dr. (Springfield Dr.) Congleton Congleton 9 Clayton By-Pass from River Dane to Barn Rd RA Congleton Congleton Clayton By-Pass From Barn Rd RA to traffic lights Rood Hill 10 Congleton Congleton 11 Clayton By-Pass from Barn Rd RA to traffic lights Rood Hill on Congleton Tescos side 12 Cockshuts from Silver St/Canal St towards St Peters Congleton Congleton Cookesmere Lane Sandbach 375199,361652 Swallow Dv to 13 Congleton Dove Cl 14 Coronation Crescent/Mill Hill Lane Sandbach link path Congleton 15 Dale Place on lhs travelling down 386982,362894 Congleton Congleton Dane Close/Cranberry Moss between 20 & 34 link path 16 Congleton Congleton 17 Edinburgh Rd. -

Middlewich Before the Romans

MIDDLEWICH BEFORE THE ROMANS During the last few Centuries BC, the Middlewich area was within the northern territories of the Cornovii. The Cornovii were a Celtic tribe and their territories were extensive: they included Cheshire and Shropshire, the easternmost fringes of Flintshire and Denbighshire and parts of Staffordshire and Worcestershire. They were surrounded by the territories of other similar tribal peoples: to the North was the great tribal federation of the Brigantes, the Deceangli in North Wales, the Ordovices in Gwynedd, the Corieltauvi in Warwickshire and Leicestershire and the Dobunni to the South. We think of them as a single tribe but it is probable that they were under the control of a paramount Chieftain, who may have resided in or near the great hill‐fort of the Wrekin, near Shrewsbury. The minor Clans would have been dominated by a number of minor Chieftains in a loosely‐knit federation. There is evidence for Late Iron Age, pre‐Roman, occupation at Middlewich. This consists of traces of round‐ houses in the King Street area, occasional finds of such things as sword scabbard‐fittings, earthenware salt‐ containers and coins. Taken together with the paleo‐environmental data, which hint strongly at forest‐clearance and agriculture, it is possible to use this evidence to create a picture of Middlewich in the last hundred years or so before the Romans arrived. We may surmise that two things gave the locality importance; the salt brine‐springs and the crossing‐points on the Dane and Croco rivers. The brine was exploited in the general area of King Street, and some of this important commodity was traded far a‐field. -

Der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr

26 . 3 . 84 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 82 / 67 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . Februar 1984 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75 /268 / EWG ( Vereinigtes Königreich ) ( 84 / 169 / EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN GEMEINSCHAFTEN — Folgende Indexzahlen über schwach ertragsfähige Böden gemäß Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe a ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden bei der Bestimmung gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro jeder der betreffenden Zonen zugrunde gelegt : über päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft , 70 % liegender Anteil des Grünlandes an der landwirt schaftlichen Nutzfläche , Besatzdichte unter 1 Groß vieheinheit ( GVE ) je Hektar Futterfläche und nicht über gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG des Rates vom 65 % des nationalen Durchschnitts liegende Pachten . 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berggebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebieten ( J ), zuletzt geändert durch die Richtlinie 82 / 786 / EWG ( 2 ), insbe Die deutlich hinter dem Durchschnitt zurückbleibenden sondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2 , Wirtschaftsergebnisse der Betriebe im Sinne von Arti kel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe b ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG wurden durch die Tatsache belegt , daß das auf Vorschlag der Kommission , Arbeitseinkommen 80 % des nationalen Durchschnitts nicht übersteigt . nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments ( 3 ), Zur Feststellung der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buchstabe c ) der Richtlinie 75 / 268 / EWG genannten geringen Bevöl in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : kerungsdichte wurde die Tatsache zugrunde gelegt, daß die Bevölkerungsdichte unter Ausschluß der Bevölke In der Richtlinie 75 / 276 / EWG ( 4 ) werden die Gebiete rung von Städten und Industriegebieten nicht über 55 Einwohner je qkm liegt ; die entsprechenden Durch des Vereinigten Königreichs bezeichnet , die in dem schnittszahlen für das Vereinigte Königreich und die Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten Gebiete Gemeinschaft liegen bei 229 beziehungsweise 163 . -

Appendix 4 Detailed Proposals for Each Ward – Organised by Local Area Partnership (LAP)

Appendix 4 Detailed proposals for each Ward – organised by Local Area Partnership (LAP) Proposed Wards within the Knutsford Local Area Partnership Knutsford Local Area Partnership (LAP) is situated towards the north-west of Cheshire East, and borders Wilmslow to the north-east, Macclesfield to the south-east and Congleton to the south. The M6 and M56 motorways pass through this LAP. Hourly train services link Knutsford, Plumley and Mobberley to Chester and Manchester, while in the east of this LAP hourly trains link Chelford with Crewe and Manchester. The town of Knutsford was the model for Elizabeth Gaskell's novel Cranford and scenes from the George C. Scott film Patton were filmed in the centre of Knutsford, in front of the old Town Hall. Barclays Bank employs thousands of people in IT and staff support functions at Radbroke Hall, just outside the town of Knutsford. Knutsford is home to numerous sporting teams such as Knutsford Hockey Club, Knutsford Cricket Club, Knutsford Rugby Club and Knutsford Football Club. Attractions include Tatton Park, home of the RHS Flower show, the stately homes Arley Hall, Tabley House and Peover Hall, and the Cuckooland Museum of cuckoo clocks. In detail, the proposals are: Knutsford is a historic, self-contained urban community with established extents and comprises the former County Ward of Knutsford, containing 7 polling districts. The Parish of Knutsford also mirrors the boundary of this proposal. Knutsford Town is surrounded by Green Belt which covers 58% of this proposed division. The proposed ward has excellent communications by road, motorway and rail and is bounded to the north by Tatton Park and to the east by Birkin Brook. -

NEWBOLD ASTBURY CUM MORETON PARISH COUNCIL Clerk C

NEWBOLD ASTBURY CUM MORETON PARISH COUNCIL Clerk C. Pointon, The Hollies, Newcastle Road, Astbury, Congleton, phone 01260 274891 [email protected] MINUTES OF A MEETING OF THE PARISH COUNCIL HELD AT ASTBURY VILLAGE HALL ON WEDNESDAY 9 APRIL 2014 AGENDA APOLOGIES PARISHIONER QUESTIONS 1 MINUTES OF MEETING HELD 12 MARCH 2013 2 PROGRESS REPORT ON PREVIOUS MINUTE MATTERS 3 PARISH ACTION PLAN REPORTS 4 CORRESPONDENCE 5 FINANCIAL MATTERS 6 PLANNING MATTERS 7 MEMBERS ITEMS – as advised C POINTON CLERK MAY 2014 PRESENT Chairman plus Cllrs SA Banks. J & P Critchlow, Kennerley, L &R Lomas, Sharman, Stanway & Sutton. CE Cllr Rhoda Bailey in attendance. APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE Cllrs A Banks, Cliff. QUESTIONS There were no parishioner questions. ITEM 1 – MINUTES Minutesof meeting held 12 March 2014 were agreed and signed a true record. ITEM 2 – PROGRESS REPORTS UPDATED REPORTS ARE NOW INCLUDED IN THESE MINUTES. 2.2 PLANNING INVESTIGATIONS Lavender House, Gorse Lane – this property is advertised at Browns Estate Agents, Congleton at £150,000. Matter to be discussed further at May meeting. 2.3 PLANNING APPLICATION DECISIONS Decisions entered as in item 2.3 of these minutes. ITEM 3 – PARISH ACTION PLAN REPORTS 3.1 Environment & Housing (JKC) Chairman to report. 3.2 Traffic/Road Use (NS) All covered under agenda item 2 re Cheshire East Highways. 3.3 Website (NS) Cllr Sharman to report re updating of website. 3.4 Social & Leisure (LL&RL) (i) Tree planting – Trees have been obtained by the Chairman. Clerk to arrange inspection of Village Green tree. (ii) Flower Bed by A34 – Chairman to provide plan. -

Open Spaces Summary Report: Congleton 1 Socio-Economic Profile

Contents 1 Socio-Economic Profile 2 2 PPG17 Typology Summary 3 Type 1: Parks & Gardens 3 Type 2: Natural & Semi-Natural Urban Greenspaces 4 Type 3: Green Corridors 5 Type 4: Outdoor Sports Facilities 6 Type 5: Amenity Greenspace 8 Type 6: Provision for Children & Teenagers 9 Type 7: Allotments, Community Gardens & Urban Farms 11 Type 8: Cemeteries & Churchyards 11 Type 9: Accessible Countryside in Urban Fringe Areas 12 Type 10: Civic Spaces 13 3 Conclusion 14 Appendices A Quality Report 16 B Outdoor Sports Facilities Report (Type 4) 17 C Provision for Children & Teenagers Report (Type 6) 20 D Potential Future Site Upgrade Information 22 Open Spaces Summary Report: Congleton 1 Socio-Economic Profile 1 Socio-Economic Profile 1.1 Congleton is a historic market town with a population of 26,580. It lies on the River Dane in the east of the Borough. In its early days it was an important centre of textile production, today, however, it is important for light engineering. The town also acts as a dormitory settlement for Manchester, Macclesfield and Stoke-on-Trent. 1.2 Congleton has a reasonably vibrant town centre. It is served by several bus routes, has its own train station with direct services between Stoke-on-Trent and Manchester and the M6 is a short distance away. 1.3 Congleton is surrounded by Green Belt to the south and east and the Jodrell Bank Telescope Consultation Zone applies to the countryside to the north east of the town. There are flood risk areas along the River Dane, Dane-in-Shaw Brook and Loach Brook. -

The Congleton Accounts: Further Evidence of Elizabethan and Jacobean Drama in Cheshire

ALAN C . COMAN The Congleton accounts: further evidence of Elizabethan and Jacobean drama in Cheshire Last summer, while conducting my research into the influence on Elizabethan and Jacobean drama of schoolmasters and household tutors in the northwest of England - viz, Cheshire, Lancashire, Shropshire (Salop) and Westmorland (Cumbria) - I came across some evidence of dramatic activities in Congleton that I believe are as yet undocumented but are significant in several respects . Since it was a chance discovery right at the end of my stay, what is presented here is only a cursory examination of the records, not a thorough and complete study . In the Cheshire County Record Office, I had occasion to consult Robert Head's Congleton Past and Present, published in 1887 and republished presumably as a centenary tribute in 1987, and History of Congleton, edited by W .B. Stephens and published in 1970 to celebrate the 700th anniversary of the town's royal charter.' Although my immediate concern was with the history of Congleton Grammar School and any possible dramatic activity connected with it, I was struck by references to the town's notorious week-long cockfights and bearbaits, and the even more intriguing assertions that the cockpit was usually in the school and that the schoolmaster was the controller and director of the pastime, reclaiming all runaway cocks as his own rightful perquisites . Head's book gave an entry from the borough's accounts : `1601. Payd John Wagge for dressyige the schoolhouse at the great cock fyghte . ..0.0.4d'. Because the aforementioned sports and pastimes were said to have drawn all the local gentry and nobility to the schoolhouse, the schoolmaster might also have undertaken some dramatic activities ; the town could have attracted touring companies at such times . -

Cheshire East – Area Profile (Spring 2015)

Appendix 1 Cheshire East – Area Profile (spring 2015) Introduction Cheshire East is the third biggest unitary authority in the North West and the thirteenth largest in the country. It therefore has a wide breadth of social grades, age profiles and ranges of affluence. There is a clear link between these measures and the likelihood of a person gambling. It also needs to be acknowledged that there are clear differences between the type of person who gambles responsibly and the type who is identified as a problem gambler. This profile with therefore concentrate on the on the measures that can contribute to gambling and problem gambling. People Cheshire East an estimated population of 372,7001, the population density is 3.2 residents per hectare2, making Cheshire East less densely populated than the North West (5.0 per hectare) and England (4.1 per hectare). Between the 2001 and 2011 Census, the median age of residents has increased from 40.6 years to 43.6 years3. Between the same years, the number of over 65s has increased by 11,700 residents or 26%, which is a greater increase than the North West (15%) and England & Wales (20%). 1 2013 Mid-year population estimates, Office for National Statistics, NOMIS, Crown Copyright 2 2011 Mid-year population estimates and UK Standard Area Measurements (SAM) 2011, Office for National Statistics, Crown Copyright 3 2001 and 2011 Census, Office for National Statistics, Crown Copyright From 2011 to 2021 the population is expected to increase by 15,700 people (4.2%) to 385,800, a greater increase than the North West (3.7%) but less than England (7.5%)4. -

Advisory Visit River Dane, Hug Bridge Macclesfield Fly Fishers 2Nd

Advisory Visit River Dane, Hug Bridge Macclesfield Fly Fishers 2nd October, 2008 1.0 Introduction This report is the output of a site visit undertaken by Tim Jacklin of the Wild Trout Trust on the River Dane, at Hug Bridge on the Cheshire/Derbyshire boundary on 2nd October 2008. Comments in this report are based on observations on the day of the site visit and discussions with Eric Jones, Frances Frakes, Les Walker and David Harrop of Macclesfield Flyfishers Club (MFC) and Kevin Nash and Stephen Cartledge of the Environment Agency (EA), North West Region. Normal convention is applied throughout the report with respect to bank identification, i.e. the banks are designated left hand bank (LHB) or right hand bank (RHB) whilst looking downstream. 2.0 Fishery Overview Macclesfield Flyfishers Club has been in existence for 55 years and currently has about 90 members. The club own the fishing rights to the Hug Bridge stretch of the River Dane and it is their longest-held fishery. At the downstream limit of the fishery (SJ 9309 6360) is a United Utilities abstraction pumping station and a gauging weir (Photo 1). The upstream limit some 1.5 km upstream is at the confluence with the Shell Brook (SJ 9413 6388). The club stock 400 brown trout of around 7 inches in length each year, in two batches during April and May. These are sourced from Dunsop Bridge trout farm, and it not certain if these are diploid (fertile) or triploid (non- breeding fish). The river is also stocked upstream of the MFC stretch. -

Wtl International Ltd, Tunstall Road, Bosley

Application No: 13/4749W Location: W T L INTERNATIONAL LTD, TUNSTALL ROAD, BOSLEY, CHESHIRE, SK11 0PE Proposal: Installation of a 4.8MW combined heat and power plant together with the extension of an existing industrial building and the erection of external plant and machinery including the erection of a 30m exhaust stack Applicant: BEL (NI) Ltd. Expiry Date: 10-Feb-2014 SUMMARY RECOMMENDATION Approve subject to conditions MAIN ISSUES • Sustainable waste management • Renewable energy • Alternative sites • Countryside beyond Green Belt • Noise and disruption • Air quality • Highways • Landscape and visual • Ecology • Water resources and flood risk REASON FOR REPORT The application has been referred to Strategic Planning Board as the proposal involves a major waste application. DESCRIPTION OF SITE AND CONTEXT The application site lies within an existing wood recycling facility in Bosley which is operated by Wood Treatment Limited. The site is located off Tunstall Road which connects to the A523. The site is approximately 800m south west of Bosley and approximately 6km east of Congleton and 8km south of Macclesfield. The wood recycling facility lies on a linear strip of land which is located in a valley directly adjacent to the River Dane. It is characterised by a mixture of traditional red-bricked and modern steel framed industrial buildings with items of externally located processing plant and machinery and part of the facility is split by Tunstall Road. The site benefits from a substantial belt of natural screening provided by woodland aligning the River Dane to the west. The surrounding land is used for agriculture and there are two farms located to the east of the site, and a smaller industrial complex to the north. -

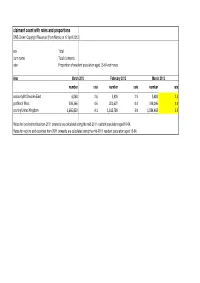

Claimant Unemployment Data

claimant count with rates and proportions ONS Crown Copyright Reserved [from Nomis on 17 April 2013] sex Total item name Total claimants rate Proportion of resident population aged 16-64 estimates Area March 2012 February 2013 March 2013 number rate number rate number rate uacounty09:Cheshire East 6,060 2.6 5,905 2.5 5,883 2.5 gor:North West 209,366 4.6 201,607 4.4 198,096 4.4 country:United Kingdom 1,666,859 4.1 1,613,789 3.9 1,584,468 3.9 Rates for local authorities from 2011 onwards are calculated using the mid-2011 resident population aged 16-64. Rates for regions and countries from 2011 onwards are calculated using the mid-2011 resident population aged 16-64. JSA count in Population (from LSOA01CD LSOA11CD LSOA11NM CHGIND March 2013 2011 Census) Claimant rate Settlement E01018574 E01018574 Cheshire East 012C U 23 1250 1.8 Alderley Edge E01018572 E01018572 Cheshire East 012A U 7 958 0.7 Alderley Edge E01018573 E01018573 Cheshire East 012B U 6 918 0.7 Alderley Edge E01018388 E01018388 Cheshire East 040B U 70 1008 6.9 Alsager E01018391 E01018391 Cheshire East 042B U 22 1205 1.8 Alsager E01018389 E01018389 Cheshire East 040C U 16 934 1.7 Alsager E01018392 E01018392 Cheshire East 042C U 19 1242 1.5 Alsager E01018390 E01018390 Cheshire East 040D U 12 955 1.3 Alsager E01018386 E01018386 Cheshire East 042A U 8 797 1.0 Alsager E01018387 E01018387 Cheshire East 040A U 8 938 0.9 Alsager E01018450 E01018450 Cheshire East 051B U 15 1338 1.1 Audlem E01018449 E01018449 Cheshire East 051A U 10 1005 1.0 Audlem E01018579 E01018579 Cheshire East 013E -

Appendix 1: Full List of Recycle Bank Sites and Materials Collected

Appendix 1: Full List of Recycle Bank Sites and Materials Collected MATERIALS RECYCLED Council Site Address Paper Glass Plastic Cans Textiles Shoes Books Oil WEEE Owned Civic Car Park Sandbach Road, Alsager Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes No No Fanny's Croft Car Park Audley Road, Alsager Yes No No No No Yes Yes No No No Manor House Hotel Audley Road, Alsager Yes No No No No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Alsager Household Waste Hassall Road Household Waste Recycling Centre, Yes No No No No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Recycling Centre Hassall Road, Alsager, ST7 2SJ Bridge Inn Shropshire Street, Audlem, CW3 0DX Yes No No No No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Cheshire Street Car Park Cheshire Street, Audlem, CW3 0AH Yes No No No No No Yes No Yes No Lord Combermere The Square, Audlem, CW3 0AQ No Yes No No Yes No No No Yes No (Pub/Restaurant) Shroppie Fly (Pub) The Wharf, Shropshire Street, Audlem, CW3 0DX No Yes No No Yes No No No Yes No Bollington Household Waste Albert Road, Bollington, SK10 5HW Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Recycling Centre Pool Bank Car Park Palmerston Street, Bollington, SK10 5PX Yes No No No No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Boars Leigh Hotel Leek Road, Bosley, SK11 0PN No Yes No No No No No No Yes No Bosley St Mary's County Leek Road, Bosley, SK11 0NX Yes No No No No No No No Yes No Primary School West Street Car Park West Street, Congleton, CW12 1JR Yes No No No No Yes Yes No Yes No West Heath Shopping Centre Holmes Chapel Road, Congleton, CW12 4NB No Yes No No Yes Yes Yes No No No Tesco, Barn Road Barn Road, Congleton, CW12 1LR No Yes No No No Yes Yes No No No Appendix 1: Full List of Recycle Bank Sites and Materials Collected MATERIALS RECYCLED Council Site Address Paper Glass Plastic Cans Textiles Shoes Books Oil WEEE Owned Late Shop, St.