Masaryk University Faculty of Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sydney Program Guide

4/23/2021 prtten04.networkten.com.au:7778/pls/DWHPROD/Program_Reports.Dsp_SHAKE_Guide?psStartDate=09-May-21&psEndDate=15-… SYDNEY PROGRAM GUIDE Sunday 09th May 2021 06:00 am Totally Wild CC C Get inspired by all-access stories from the wild side of life! 06:30 am Top Wing (Rpt) G Rod's Beary Brave Save / Race Through Danger Canyon Rod proves that he is a rooster (and not a chicken) as he finds a cub named Baby Bear lost in the Haunted Cave. A jet-flying bat roars into Danger Canyon to show off his prowess. 07:00 am Blaze And The Monster Machines (Rpt) G Treasure Track Blaze, AJ, and Gabby join Pegwheel the Pirate-Truck for an island treasure hunt! Following their treasure map, the friends search jungle beaches and mountains to find where X marks the spot. 07:30 am Paw Patrol (Rpt) G Pups Save The Runaway Turtles / Pups Save The Shivering Sheep Daring Danny X accidently drives off with turtle eggs that Cap'n Turbot had hoped to photograph while hatching. Farmer Al's sheep-shearing machine malfunctions and all his sheep run away. 07:56 am Shake Takes 08:00 am Paw Patrol (Rpt) G Sea Patrol: Pups Save A Frozen Flounder / Pups Save A Narwhal Cap'n Turbot's boat gets frozen in the Arctic Ice. The pups use the Sea Patroller to help guide a lost narwhal back home. 08:30 am The Loud House (Rpt) G Lincoln Loud: Girl Guru / Come Sale Away For a class assignment Lincoln and Clyde must start a business. -

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak

Emotional and Linguistic Analysis of Dialogue from Animated Comedies: Homer, Hank, Peter and Kenny Speak. by Rose Ann Ko2inski Thesis presented as a partial requirement in the Master of Arts (M.A.) in Human Development School of Graduate Studies Laurentian University Sudbury, Ontario © Rose Ann Kozinski, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-57666-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Comedy Movie Trivia Questions #6

COMEDY MOVIE TRIVIA QUESTIONS #6 ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Woody Allen won the Oscar for Best Director for his work on which 1977 comedy film? a. Manhattan b. Sleeper c. Tootsie d. Annie Hall 2> Making its debut in 1999, "Bigger, Longer and Uncut" was an animated movie version of which hit TV show? a. American Dad b. Family Guy c. South Park d. The Simpsons 3> If Billy Crystal is Harry, who is Sally? a. Julia Roberts b. Demi Moore c. Rita Coolidge d. Meg Ryan 4> Playing the role of "Grover T. Muldoon", Richard Pryor teamed up with which actor in the 1976 movie "Silver Streak"? a. Kevin Costner b. Steve Martin c. James Stewart d. Gene Wilder 5> What is the surname of Kevin, who is left "Home Alone" in the classic 1990 film? a. Edwards b. Johnson c. Newcomb d. McAlister 6> Which of the following Monty Python films was the first to be released? a. Life of Brian b. Meaning of Life c. And Now For Something Complete Different d. Holy Grail 7> Who wrote the novel on which the 1967 comedy film "The Graduate" is based? a. Calder Willingham b. Robert Surtees c. Charles Webb d. Buck Henry 8> Who played the lead role of "Evan Baxter" in the 2007 film "Evan Almighty"? a. Steve Carrell b. Vince Vaughn c. Adam Sandler d. Ben Stiller 9> Warren Beatty, Goldie Hawn, Julie Christie and Lee Grant star in which 1975 comedy that is set during a 24-hour period in 1968? a. Smile b. Lost in America c. -

Gruda Mpp Me Assis.Pdf

MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM SOUTH PARK ASSIS 2011 MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM SOUTH PARK Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia (Área de Conhecimento: Psicologia e Sociedade) Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Sterza Justo Trabalho financiado pela CAPES ASSIS 2011 Dados Internacionais de Catalogação na Publicação (CIP) Biblioteca da F.C.L. – Assis – UNESP Gruda, Mateus Pranzetti Paul G885d O discurso politicamente incorreto e do escracho em South Park / Mateus Pranzetti Paul Gruda. Assis, 2011 127 f. : il. Dissertação de Mestrado – Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – Universidade Estadual Paulista Orientador: Prof. Dr. José Sterza Justo. 1. Humor, sátira, etc. 2. Desenho animado. 3. Psicologia social. I. Título. CDD 158.2 741.58 MATEUS PRANZETTI PAUL GRUDA O DISCURSO POLITICAMENTE INCORRETO E DO ESCRACHO EM “SOUTH PARK” Dissertação apresentada à Faculdade de Ciências e Letras de Assis – UNESP – Universidade Estadual Paulista para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Psicologia (Área de Conhecimento: Psicologia e Sociedade) Data da aprovação: 16/06/2011 COMISSÃO EXAMINADORA Presidente: PROF. DR. JOSÉ STERZA JUSTO – UNESP/Assis Membros: PROF. DR. RAFAEL SIQUEIRA DE GUIMARÃES – UNICENTRO/ Irati PROF. DR. NELSON PEDRO DA SILVA – UNESP/Assis GRUDA, M. P. P. O discurso do humor politicamente incorreto e do escracho em South Park. -

Outstanding Animated Program (For Programming Less Than One Hour)

Keith Crofford, Executive Producer Outstanding Animated Program (For Corey Campodonico, Producer Programming Less Than One Hour) Alex Bulkley, Producer Douglas Goldstein, Head Writer Creature Comforts America • Don’t Choke To Death, Tom Root, Head Writer Please • CBS • Aardman Animations production in association with The Gotham Group Jordan Allen-Dutton, Writer Mike Fasolo, Writer Kit Boss, Executive Producer Charles Horn, Writer Miles Bullough, Executive Producer Breckin Meyer, Writer Ellen Goldsmith-Vein, Executive Producer Hugh Sterbakov, Writer Peter Lord, Executive Producer Erik Weiner, Writer Nick Park, Executive Producer Mark Caballero, Animation Director David Sproxton, Executive Producer Peter McHugh, Co-Executive Producer The Simpsons • Eternal Moonshine of the Simpson Mind • Jacqueline White, Supervising Producer FOX • Gracie Films in association with 20th Century Fox Kenny Micka, Producer James L. Brooks, Executive Producer Gareth Owen, Producer Matt Groening, Executive Producer Merlin Crossingham, Director Al Jean, Executive Producer Dave Osmand, Director Ian Maxtone-Graham, Executive Producer Richard Goleszowski, Supervising Director Matt Selman, Executive Producer Tim Long, Executive Producer King Of The Hill • Death Picks Cotton • FOX • 20th Century Fox Television in association with 3 Arts John Frink, Co-Executive Producer Entertainment, Deedle-Dee Productions & Judgemental Kevin Curran, Co-Executive Producer Films Michael Price, Co-Executive Producer Bill Odenkirk, Co-Executive Producer Mike Judge, Executive Producer Marc Wilmore, Co-Executive Producer Greg Daniels, Executive Producer Joel H. Cohen, Co-Executive Producer John Altschuler, Executive Producer/Writer Ron Hauge, Co-Executive Producer Dave Krinsky, Executive Producer Rob Lazebnik, Co-Executive Producer Jim Dauterive, Executive Producer Laurie Biernacki, Animation Producer Garland Testa, Executive Producer Rick Polizzi, Animation Producer Tony Gama-Lobo, Supervising Producer J. -

S. Harrison 1 Trash Or Treasure in the Works of Trey Parker and Matt Stone

S. Harrison 1 Trash or Treasure in the Works of Trey Parker and Matt Stone: What’s the Difference, and Who Decides? On March 24, 2011, New York Times reporter Ben Brantley described The Book of Mormon as “the best musical of this century… Heaven on Broadway.” He praised the writers, producers, and actors for “achieving something like a miracle.” As if this weren’t enough, Brantley went on to describe the musical as “cathartic” and the characters as both “likeable and funny.” In an online video titled “Subversive, Satirical, and Sold Out” posted on June 10, 2012, 60 Minutes host Steve Kroft commends the musical, stating that tickets for The Book of Mormon were the most heartily sought and hardest to obtain on Broadway this past summer. Moreover, Kroft boasts of the creators’ “big heart” as the foundation of the musical’s success. To employ a simple Google search for The Book of Mormon – while oftentimes bringing up information on the actual book and its corresponding faith – is to call forth resounding reviews of praise from both professional and amateur critics. The performance is being described as witty and satirical, appealing to the vast majority of musical-goers. However, The Book of Mormon with its undeniable success calls forth questions and criticism prompted by the previous works of creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone. Parker and Stone are infamous for their roles as developers, producers of, and performers in South Park, a television show that, in the words of Kroft, “changed the face of cable television” with its lewd, scatological humor and sensitive (and correspondingly insensitive handling of) thematic elements. -

WORST COOKS in AMERICA: CELEBRITY EDITION Contestant Bios (2018)

Contact: Lauren Sklar Phone: 646-336-3745; Email: [email protected] WORST COOKS IN AMERICA: CELEBRITY EDITION Contestant Bios (2018) CATHERINE BACH Catherine Bach is a true American original. Kicking butt in short-shorts as Daisy Duke in the Dukes of Hazzard was the breakout role that made her a pop icon and sex symbol—and got those shorts into the Smithsonian. However, throughout her career, Catherine has proven her acting chops working alongside some of the best in the business: legends such as Robert Mitchum (African Skies), her mentor Burt Lancaster (The Midnight Man), Clint Eastwood (Thunderbolt and Lightfoot) and Burt Reynolds (Hustle, Cannonball Run II). Catherine has a unique focus and creative energy that enables her to see opportunities for success when it comes to character work and taking the banal to the extraordinary. It is thanks to Catherine’s own sense of style and imagination that Daisy Dukes are now part of the popular vernacular—her character was initially supposed to wear a poodle skirt, but Catherine asked the producers for a shot at creating the character’s wardrobe, with the idea of a more edgy look for an independent character. Catherine’s famous pin-up poster that she styled has outpaced other contemporary beauties and sold over 5 million copies. Catherine is not afraid of adventure and activism; while portraying the lead in African Skies, the first American show filmed in South Africa after Apartheid, she spearheaded the cause of preserving the endangered Black Rhinoceros and testified before U.S. Congress to protect them. She was instrumental in lobbying for the Black Rhino and Tiger Preservation act, which was passed in 1996. -

1 United States District Court for The

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ________________________________________ ) VIACOM INTERNATIONAL INC., ) COMEDY PARTNERS, ) COUNTRY MUSIC TELEVISION, INC., ) PARAMOUNT PICTURES ) Case No. 1:07-CV-02103-LLS CORPORATION, ) (Related Case No. 1:07-CV-03582-LLS) and BLACK ENTERTAINMENT ) TELEVISION LLC, ) DECLARATION OF WARREN ) SOLOW IN SUPPORT OF Plaintiffs, ) PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR v. ) PARTIAL SUMMARY JUDGMENT ) YOUTUBE, INC., YOUTUBE, LLC, and ) GOOGLE INC., ) Defendants. ) ________________________________________ ) I, WARREN SOLOW, declare as follows: 1. I am the Vice President of Information and Knowledge Management at Viacom Inc. I have worked at Viacom Inc. since May 2000, when I was joined the company as Director of Litigation Support. I make this declaration in support of Viacom’s Motion for Partial Summary Judgment on Liability and Inapplicability of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act Safe Harbor Defense. I make this declaration on personal knowledge, except where otherwise noted herein. Ownership of Works in Suit 2. The named plaintiffs (“Viacom”) create and acquire exclusive rights in copyrighted audiovisual works, including motion pictures and television programming. 1 3. Viacom distributes programs and motion pictures through various outlets, including cable and satellite services, movie theaters, home entertainment products (such as DVDs and Blu-Ray discs) and digital platforms. 4. Viacom owns many of the world’s best known entertainment brands, including Paramount Pictures, MTV, BET, VH1, CMT, Nickelodeon, Comedy Central, and SpikeTV. 5. Viacom’s thousands of copyrighted works include the following famous movies: Braveheart, Gladiator, The Godfather, Forrest Gump, Raiders of the Lost Ark, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Top Gun, Grease, Iron Man, and Star Trek. -

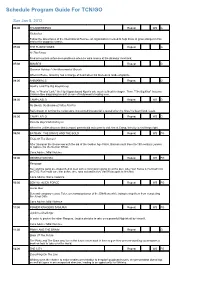

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Jan 8, 2012 06:00 THUNDERBIRDS Repeat WS G Richochet Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:00 THE FLINTSTONES Repeat G At The Races Fred encounters unforeseen problems when he wins money at the dinosaur racetrack. 07:30 SMURFS Repeat G Gnoman Holiday / The Monumental Grouch When in Rome, Grouchy has a change of heart when his likeness is made of granite. 08:00 ANIMANIACS Repeat G Noah's Lark/The Big Kiss/Hiccup First, in "Noahs' Lark," the Hip Hippos board Noah's ark, much to Noah's chagrin. Then, "The Big Kiss" features Chicken Boo disguising himself as one of Hollywood's leading men. 08:30 CAMP LAZLO Repeat WS G No Beads, No Business!/ Miss Fru Fru Raj's dream of turning the camp store into something special is tested when he hires his best friend, Lazlo. 09:00 CAMP LAZLO Repeat WS G Parents Day/ Club Kidney-ki When the Jellies discover that Lumpus' parents did not come to visit him at Camp, they try to set things right. 09:30 BATMAN: THE BRAVE AND THE BOLD Repeat WS PG Trials Of The Demon! After taking on the Scarecrow with the aid of the Golden Age Flash, Batman must travel to 19th century London to capture the Gentleman Ghost. Cons.Advice: Mild Violence 10:00 GENERATOR REX Repeat WS PG Rampage Rex and the gang are dispatched to deal with a commotion going on at the port. -

December 3, 2004 the Opening Scene of Team America

Originally Published on Kikizo.com - December 3, 2004 The opening scene of Team America: World Police , the latest ribald comic masterpiece from South Park creators Matt Stone and Trey Parker, is amongst the funniest vignettes ever filmed. As the team in question, a band of jingoistic gun-toting marionettes, duke it out on the streets of Paris with hilariously stereotyped, weapon of mass destruction wielding terrorists, they manage to accidentally level the Eiffel Tower, the Arch de Triumph, and the Louver, leaving the centre of the city a steaming pile of rubble. In ten frenetic minutes Parker and Stone manage to satirise not just soldier of fortune diplomacy, but the films bizarrely chosen medium, puppetry; so acerbically and astutely that the hardened critics at the showing I attended were almost literally in tears. While the film's remaining eigty-eight minutes don't posses quite the same distilled comic genius, they are undeniably entertaining. Ironically, just as the South Park boys have chosen to adopt what could be perceived as their most adolescent medium yet - puppetry - they've managed to attain a satirical poignancy more adult than anything they've previously produced. Which is not to say that Team America doesn't contain more than its share of perversely offensive humour. At times the movie ventures into territory at least as offensive as anything previous hit 'South Park: Bigger Longer & Uncut' dared to depict. Yet while South Park struggled to fill a feature length run time - recycling many of the TV series' staples, ultimately achieving little more than a mildly humorous extended episode; by contrast Team America manages to work as a coherent, entertaining film. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 13, 2008 6:00 PM PDT

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE September 13, 2008 6:00 PM PDT The Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (ATAS) tonight (Saturday, September 13, 2008) awarded the 2007-2008 Creative Arts Primetime Emmys for programs and individual achievements at the 60th Annual Emmy Awards presentation at the NOKIA Theatre L.A. LIVE in Los Angeles. Included among the presentations were Emmy Awards for the following previously announced categories: Outstanding Individual Achievement in Animation, Outstanding Voice-Over Performance, Outstanding Costumes for a Variety/ Music Program or a Special, Outstanding Achievement in Engineering Development. Additionally, the Governors Award was presented to National Geographic Channel’s “Preserve Our Planet” Campaign. ATAS Chairman & CEO John Shaffner participated in the awards ceremony assisted by a lineup of major television stars as presenters. The awards, as tabulated by the independent accounting firm of Ernst & Young LLP, were distributed as follows: Programs Individuals Total HBO 4 12 16 ABC - 9 9 PBS 3 6 9 CBS 1 7 8 NBC - 6 6 AMC - 5 5 SHOWTIME 1 4 5 FOX 1 2 3 BRAVO 1 1 2 CARTOON NETWORK 1 1 2 SCI FI CHANNEL - 2 2 COMEDY CENTRAL 1 - 1 CW - 1 1 DISCOVERY CHANNEL - 1 1 DISNEY CHANNEL 1 - 1 FX NETWORKS - 1 1 NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CHANNEL 1 - 1 ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS AND SCIENCES 60TH ANNUAL PRIMETIME EMMY AWARDS NBC.COM 1 - 1 NICKELODEON 1 - 1 SCI FI CHANNEL.COM 1 - 1 TBS - 1 1 THE HISTORY CHANNEL/ VOD 1 - 1 TNT - 1 1 At a previous awards ceremony on Saturday, August 23, the following awards for Outstanding Achievement in Engineering Development were announced: Engineering Plaque to: The Charles F. -

Lt Col Andrew Tanner

Lt col andrew tanner Continue This article is about the 1984 film. For the 2012 remake, watch the film Red Dawn (2012). For other purposes, see Red Dawn (disambiguation). 1984 action movie directed by John Milius Red DawnOriginal theatrical poster John AlvinDirector John MiliusProduzyBuzz FeitshansBarry BeckermanSidney BeckermanScreenplay Kevin ReynoldsJohn MiliusStroy Kevin ReynoldsStarring Patrick Swayze C. Thomas Howell Lea Thompson Ben Johnson Harry Dean Stanton Ron O'Neill William Smith Powers Booth Music Poseila PoledourisCinematographyRic WaiteEdited byThom NobleProductioncompany United ArtistsValkyrie FilmsDistributed byMGM/UA Entertainment CompanyRelease Date August 10, 1984 (1984-08-10) 114 minutes(114 minutes) - American action film directed by John Milius in 1984, Red Dawn, based on the screenplay by Kevin Reynolds and Milius. Starring Patrick Swayze, Charlie Sheen, C. Thomas Howell, Lea Thompson, Jennifer Gray, Ben Johnson, Harry Dean Stanton, Ron O'Neill, William Smith, and Powers Booth. It was the first film released in the United States with a PG-13 rating (according to the modified rating system introduced on July 1, 1984). The film depicts the United States, captured by the Soviet Union and its Cuban and Nicaraguan allies. However, the beginning of the Third World War is in the background and has not been fully worked out. The story follows a group of American schoolchildren who resist occupation with guerrilla warfare, calling themselves Wolverines, after their high school mascot. The United States became strategically isolated after NATO was completely dissolved. At the same time, the Soviet Union and its Allies under the Warsaw Pact are actively expanding their sphere of influence. In addition, the Ukrainian wheat crop fails, while in Mexico there is a socialist coup d'etat.