Latter-Day Screens Gender, Sexuality & Mediated Mormonism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought

DIALOGUE PO Box 1094 Farmington, UT 84025 electronic service requested DIALOGUE 52.3 fall 2019 52.3 DIALOGUE a journal of mormon thought EDITORS DIALOGUE EDITOR Boyd Jay Petersen, Provo, UT a journal of mormon thought ASSOCIATE EDITOR David W. Scott, Lehi, UT WEB EDITOR Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT FICTION Jennifer Quist, Edmonton, Canada POETRY Elizabeth C. Garcia, Atlanta, GA IN THE NEXT ISSUE REVIEWS (non-fiction) John Hatch, Salt Lake City, UT REVIEWS (literature) Andrew Hall, Fukuoka, Japan Papers from the 2019 Mormon Scholars in the INTERNATIONAL Gina Colvin, Christchurch, New Zealand POLITICAL Russell Arben Fox, Wichita, KS Humanities conference: “Ecologies” HISTORY Sheree Maxwell Bench, Pleasant Grove, UT SCIENCE Steven Peck, Provo, UT A sermon by Roger Terry FILM & THEATRE Eric Samuelson, Provo, UT PHILOSOPHY/THEOLOGY Brian Birch, Draper, UT Karen Moloney’s “Singing in Harmony, Stitching in Time” ART Andi Pitcher Davis, Orem, UT BUSINESS & PRODUCTION STAFF Join our DIALOGUE! BUSINESS MANAGER Emily W. Jensen, Farmington, UT PUBLISHER Jenny Webb, Woodinville, WA Find us on Facebook at Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought COPY EDITORS Richelle Wilson, Madison, WI Follow us on Twitter @DialogueJournal Jared Gillins, Washington DC PRINT SUBSCRIPTION OPTIONS EDITORIAL BOARD ONE-TIME DONATION: 1 year (4 issues) $60 | 3 years (12 issues) $180 Lavina Fielding Anderson, Salt Lake City, UT Becky Reid Linford, Leesburg, VA Mary L. Bradford, Landsdowne, VA William Morris, Minneapolis, MN Claudia Bushman, New York, NY Michael Nielsen, Statesboro, GA RECURRING DONATION: Verlyne Christensen, Calgary, AB Nathan B. Oman, Williamsburg, VA $10/month Subscriber: Receive four print issues annually and our Daniel Dwyer, Albany, NY Taylor Petrey, Kalamazoo, MI Subscriber-only digital newsletter Ignacio M. -

The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922

University of Nevada, Reno THE SECRET MORMON MEETINGS OF 1922 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History By Shannon Caldwell Montez C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D. / Thesis Advisor December 2019 Copyright by Shannon Caldwell Montez 2019 All Rights Reserved UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA RENO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by SHANNON CALDWELL MONTEZ entitled The Secret Mormon Meetings of 1922 be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS C. Elizabeth Raymond, Ph.D., Advisor Cameron B. Strang, Ph.D., Committee Member Greta E. de Jong, Ph.D., Committee Member Erin E. Stiles, Ph.D., Graduate School Representative David W. Zeh, Ph.D., Dean, Graduate School December 2019 i Abstract B. H. Roberts presented information to the leadership of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in January of 1922 that fundamentally challenged the entire premise of their religious beliefs. New research shows that in addition to church leadership, this information was also presented during the neXt few months to a select group of highly educated Mormon men and women outside of church hierarchy. This group represented many aspects of Mormon belief, different areas of eXpertise, and varying approaches to dealing with challenging information. Their stories create a beautiful tapestry of Mormon life in the transition years from polygamy, frontier life, and resistance to statehood, assimilation, and respectability. A study of the people involved illuminates an important, overlooked, underappreciated, and eXciting period of Mormon history. -

Teaching Like a Spiritual Rock Star

Teaching Like a Spiritual Rock Star Jeff Birk LLDS: So Jeff, how are you? Birk: I'm doing great, Kirk. Thanks for having me on. This is just an honor (00:00:30) and I am really excited to share some cool stuff with everybody. LLDS: Nice. Well maybe one thing and I want you to tell us a little about yourself, but just so nobody sits here and is distracted by what you're saying by thinking I've seen that guy somewhere. Where maybe somebody in the Mormon universe recognize you? Birk: So I've done a few Mormon Movies. You know, if anyone wants to think way back to when this whole thing started. When it really started to get (00:01:00) a lot of momentum was when the first "Singles Ward" movie came out. So I had a small role in the "Singles Ward" and the "Singles Ward 2" or the single second ward. I did some voiceover stuff for the "Saints and Soldiers" movies that, uh, that depict members of the church during a certain happenings during World War Two primarily. But I think that the big one that people might recognize me from is the "Home Teachers" where I co-started with Michael Berkland who's done a lot of stuff. So I was kind of the, you know, (00:01:30) the really, we got to get our home teaching done. And my co-star was the we gotta get home and watch the football game. But yeah, other than that, that's pretty much been where people might spot me and Costco and start following me around. -

2014–2015 Season Sponsors

2014–2015 SEASON SPONSORS The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2014–2015 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at 562-916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following current CCPA Associates donors who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue where patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. MARQUEE Sandra and Bruce Dickinson Diana and Rick Needham Eleanor and David St. Clair Mr. and Mrs. Curtis R. Eakin A.J. Neiman Judy and Robert Fisher Wendy and Mike Nelson Sharon Kei Frank Jill and Michael Nishida ENCORE Eugenie Gargiulo Margene and Chuck Norton The Gettys Family Gayle Garrity In Memory of Michael Garrity Ann and Clarence Ohara Art Segal In Memory Of Marilynn Segal Franz Gerich Bonnie Jo Panagos Triangle Distributing Company Margarita and Robert Gomez Minna and Frank Patterson Yamaha Corporation of America Raejean C. Goodrich Carl B. Pearlston Beryl and Graham Gosling Marilyn and Jim Peters HEADLINER Timothy Gower Gwen and Gerry Pruitt Nancy and Nick Baker Alvena and Richard Graham Mr. -

Preach My Gospel (D&C 50:14)

A Guide to Missionary Service reach My Gospel P (D&C 50:14) “Repent, all ye ends of the earth, and come unto me and be baptized in my name, that ye may be sanctified by the reception of the Holy Ghost” (3 Nephi 27:20). Name: Mission and Dates of Service: List of Areas: Companions: Names and Addresses of People Baptized and Confirmed: Preach My Gospel (D&C 50:14) Published by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Salt Lake City, Utah Cover: John the Baptist Baptizing Jesus © 1988 by Greg K. Olsen Courtesy Mill Pond Press and Dr. Gerry Hooper. Do not copy. © 2004 by Intellectual Reserve, Inc. All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America English approval: 01/05 Preach My Gospel (D&C 50:14) First Presidency Message . v Introduction: How Can I Best Use Preach My Gospel? . vii 1 What Is My Purpose as a Missionary? . 1 2 How Do I Study Effectively and Prepare to Teach? . 17 3 What Do I Study and Teach? . 29 • Lesson 1: The Message of the Restoration of the Gospel of Jesus Christ . 31 • Lesson 2: The Plan of Salvation . 47 • Lesson 3: The Gospel of Jesus Christ . 60 • Lesson 4: The Commandments . 71 • Lesson 5: Laws and Ordinances . 82 4 How Do I Recognize and Understand the Spirit? . 89 5 What Is the Role of the Book of Mormon? . 103 6 How Do I Develop Christlike Attributes? . 115 7 How Can I Better Learn My Mission Language? . 127 8 How Do I Use Time Wisely? . -

Donny Osmond Returns to the Las Vegas Stage with First-Ever Solo Residency at Harrah's Las Vegas

Donny Osmond Returns To The Las Vegas Stage With First-Ever Solo Residency At Harrah's Las Vegas November 20, 2020 Tickets go on sale starting Tuesday, Nov. 24, 2020 Shows begin Tuesday, Aug. 31, 2021 LAS VEGAS, Nov. 20, 2020 /PRNewswire/ -- Legendary entertainer and music icon, Donny Osmond, today announced his return to Las Vegas and the Caesars Entertainment family with his first-ever solo multi-year residency inside Harrah's Showroom at Harrah's Las Vegas, opening Tuesday, Aug. 31, 2021. "Donny Osmond has achieved a lifetime of remarkable milestones as an entertainer, including countless memories with us during his 11-year run at Flamingo," said Caesars Entertainment Regional President Gary Selesner. "We're thrilled to welcome him to the stage at Harrah's Las Vegas next summer for an all-new show, and we look forward to sharing many more unforgettable moments with our guests and one of music's most beloved stars." In an unprecedented and history-making deal for Harrah's, Osmond's return to stage will be an exciting, energy-filled musical journey of his unparalleled life as one of the most recognized entertainers in the world. Guests can expect a party as he performs his timeless hits, shares stories of his greatest showstopping memories and introduces brand new music in a completely reimagined song and dance celebration. The announcement comes almost exactly one year after the curtains closed for the final time on his previous record-breaking 11-year residency at Flamingo Las Vegas. Fans can once again experience an unforgettable night with Donny Osmond – exclusively at Harrah's Las Vegas. -

The Mormon Culture of Community and Recruitment

The Mormon Culture of Community and Recruitment Source:http://www.allaboutmormons.com/IMG/MormonImages/mormon-scriptures/book-of-mormon-many-languages.jpg Thesis by Tofani Grava Wheaton College, Department of Anthropology Spring, 2011 1 Table of Contents Page Chapter I: Introduction 4 Chapter II: Methodology 8 1. Research Phases 8 2. My Informants and Fieldsites 11 3. Ethical Considerations 12 4. Challenges Encountered 13 Chapter III: Literature Review 15 I. Historical Framework 15 II. Theoretical Framework 17 A. Metatheoretical Framework 17 1. Theories of religion and community 17 2. Religious rituals and rites of passage 19 3. Millenarian movements 21 4. Fundamentalism 22 5. Charisma 24 B. The logic of Faith in Christianity in 21st Century America 25 1. The function of American Churches in contemporary 25 American society 28 2. Modern Techniques of membership recruitment 29 3. Religious conversion III. Analyses of Mormonism 31 A. Processes of socialization and the Mormon subculture 31 1. A Family-oriented theology 31 2. Official Mormon religious rhetoric 32 3. The prophetic figure 34 B. Mormon Conversion 35 1. Missionary work and volunteer labor force 35 2. Mormonism as millenarian 37 IV. Online Communities: Theoretical Overview 38 A. Virtual Culture 38 1. The Interaction logic of virtual communities 38 2. The Virtual Self 40 3. The Interpenetration of public and private spheres 42 4. Virtual Communities as instruments for change 43 43 2 Page B. Religion and Technology in Modern America 46 1. A New Religious Landscape 46 2. Religious representation online 49 3. Praising Technology 51 IV. Twenty-First Century Mormonism and the Internet 54 A. -

Gospel Principles

The Law of Chastity Chapter 39 A Note to Parents This chapter includes some parts that are beyond the maturity of young children . It is best to wait until children are old enough to understand sexual relations and procreation before teaching them these parts of the chapter . Our Church leaders have told us that parents are responsible to teach their children about procreation (the process of conceiving and bearing children) . Parents must also teach them the law of chastity, which is explained in this chapter . Parents can begin teaching children to have proper attitudes toward their bodies when children are very young . Talking to children frankly but reverently and using the correct names for the parts and functions of their bodies will help them grow up without unneces- sary embarrassment about their bodies . Children are naturally curious . They want to know how their bod- ies work . They want to know where babies come from . If parents answer all such questions immediately and clearly so children can understand, children will continue to take their questions to their parents . However, if parents answer questions so that children feel embarrassed, rejected, or dissatisfied, they will probably go to someone else with their questions and perhaps get incorrect ideas and improper attitudes . It is not wise or necessary, however, to tell children everything at once . Parents need only give them the information they have asked for and can understand . While answering these questions, parents can teach children the importance of respecting their bodies and the bodies of others . Parents should teach children to dress mod- estly . -

Vol. 05 No. 2 Religious Educator

Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel Volume 5 Number 2 Article 12 7-1-2004 Vol. 05 No. 2 Religious Educator Religious Educator Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Educator, Religious. "Vol. 05 No. 2 Religious Educator." Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel 5, no. 2 (2004). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/re/vol5/iss2/12 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Religious Educator: Perspectives on the Restored Gospel by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. THE RELIGIOUS EDUCATOR • PERSPECTIVES ON THE RESTORED GOSPEL The Joseph Smith Translation INSIDE THIS ISSUE: “The Best Two Years of Our Lives” Teaching the Fall and the Atonement The One Pure Defense President Boyd K. Packer VOL 5 NO 2 • 2004 “A Miracle from Day One”: Publication of the Joseph Smith Translation Manuscripts Rebecca L. McConkie A Light in the Wilderness: Robert J. Matthews and His Work on the Joseph Smith Translation Ray L. Huntington and Brian M. Hauglid A Community of Christ Perspective on the JST Research of Robert J. Matthews: An Interview with Ronald E. Romig Brian M. Hauglid and Ray L. Huntington Precious Truths Restored: RELIGIOUS STUDIES CENTER • BRIGHAM YOUNG UNIVERSITY Joseph Smith Translation Changes Not Included in Our Bible W. Jeffrey Marsh and Thomas E. Sherry “The Best Two Years of Our Lives”: A CES Mission Remembered Ed and Bunkie Griffith Endowed with Power Steven C. -

Luna Lindsey Sample Chapters

Recovering Agency: Lifting the Veil of Mormon Mind Control by LUNA LINDSEY Recovering Agency: Lifting the Veil of Mormon Mind Control Copyright ©2013-2014 by Luna Flesher Lindsey Internal Graphics ©2014 by Luna Flesher Lindsey Cover Art ©2014 by Ana Cruz All rights reserved. This publication is protected under the US Copyright Act of 1976 and all other applicable international, federal, state and local laws. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles, professional works, or reviews. www.lunalindsey.com ISBN-10: 1489595937 ISBN-13: 978-1489595935 First digital & print publication: July 2014 iv RECOVERING AGENCY Table of Contents FOREWORD' VIII' PART%1:%IN%THE%BEGINNING% ' IT'STARTED'IN'A'GARDEN…' 2' Free$Will$vs.$Determinism$ 3' Exit$Story$ 5' The$Illusion$of$Choice$ 9' WHAT'IS'MIND'CONTROL?' 13' What$is$a$Cult?$ 16' Myths$of$Cults$&$MinD$Control$ 17' ALL'IS'NOT'WELL'IN'ZION' 21' Is$Mormonism$A$DanGer$To$Society?$ 22' Why$ShoulD$We$Mourn$Or$Think$Our$Lot$Is$HarD?$ 26' Self<esteem' ' Square'Peg,'Round'Hole'Syndrome' ' Guilt'&'Shame' ' Depression,'Eating'Disorders,'&'Suicide' ' Codependency'&'Passive<Aggressive'Culture' ' Material'Loss' ' DON’T'JUST'GET'OVER'IT—RECOVER!' 36' Though$harD$to$you$this$journey$may$appear…$ 40' Born$UnDer$the$Covenant$ 41' We$Then$Are$Free$From$Toil$anD$Sorrow,$Too…$ 43' SLIPPERY'SOURCES' 45' Truth$Is$Eternal$$(And$Verifiable)$ 45' Truth$Is$Eternal$$(Depends$on$Who$You$Ask)$ 46' -

Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3

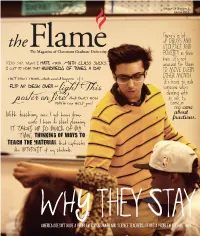

the Flame The Magazine of Claremont Graduate University Spring 2013 COME Volume 14 Number 3 The Flame is published by Claremont Graduate University 150 East Tenth Street Claremont, California 91711 ©2013 by Claremont Graduate BACK TO University Director of University Communications Esther Wiley Managing Editor Brendan Babish CAMPUS Art Director Shari Fournier-O’Leary News Editor Rod Leveque Online Editor WITHOUT Sheila Lefor Editorial Contributors Mandy Bennett Dean Gerstein Kelsey Kimmel Kevin Riel LEAVING Emily Schuck Rachel Tie Director of Alumni Services Monika Moore Distribution Manager HOME Mandy Bennett Every semester CGU holds scores of lectures, performances, and other events Photographers Marc Campos on our campus. Jonathan Gibby Carlos Puma On Claremont Graduate University’s YouTube channel you can view the full video of many William Vasta Tom Zasadzinski of our most notable speakers, events, and faculty members: www.youtube.com/cgunews. Illustration Below is just a small sample of our recent postings: Thomas James Claremont Graduate University, founded in 1925, focuses exclusively on graduate-level study. It is a member of the Claremont Colleges, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, distinguished professor of psychology in CGU’s School of a consortium of seven independent Behavioral and Organizational Sciences, talks about why one of the great challenges institutions. to positive psychology is to help keep material consumption within sustainable limits. President Deborah A. Freund Executive Vice President and Provost Jacob Adams Jack Scott, former chancellor of the California Community Colleges, and Senior Vice President for Finance Carl Cohn, member of the California Board of Education, discuss educational and Administration politics in California, with CGU Provost Jacob Adams moderating. -

No. 17-15589 in the UNITED STATES COURT of APPEALS

Case: 17-15589, 04/20/2017, ID: 10404479, DktEntry: 113, Page 1 of 35 No. 17-15589 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT STATE OF HAWAII, ET AL., Plaintiffs/Appellees v. DONALD J. TRUMP, ET AL., Defendants/Appellants. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR HAWAII THE HONORABLE DERRICK KAHALA WATSON, DISTRICT JUDGE CASE NO. 1:17-CV-00050-DKW-KSC AMICI CURIAE BRIEF OF SCHOLARS OF AMERICAN RELIGIOUS HISTORY & LAW IN SUPPORT OF NEITHER PARTY ANNA-ROSE MATHIESON BEN FEUER CALIFORNIA APPELLATE LAW GROUP LLP 96 Jessie Street San Francisco, California 94105 (415) 649-6700 ATTORNEYS FOR AMICI CURIAE SCHOLARS OF AMERICAN RELIGIOUS HISTORY & LAW Case: 17-15589, 04/20/2017, ID: 10404479, DktEntry: 113, Page 2 of 35 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ....................................................................... ii INTERESTS OF AMICI CURIAE ............................................................. 1 STATEMENT OF COMPLIANCE WITH RULE 29 ................................. 4 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................... 5 ARGUMENT ............................................................................................... 7 I. The History of Religious Discrimination Against Mormon Immigrants Demonstrates the Need for Vigilant Judicial Review of Government Actions Based on Fear of Religious Minorities ............................................... 7 A. Mormons Were the Objects of Widespread Religious Hostility in the 19th Century .......................