Anthropogenic Climate Change and Glacier Lake Outburst Flood Risk: Local

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relación De Agencias Que Atenderán De Lunes a Viernes De 8:30 A. M. a 5:30 P

Relación de Agencias que atenderán de lunes a viernes de 8:30 a. m. a 5:30 p. m. y sábados de 9 a. m. a 1 p. m. (con excepción de la Ag. Desaguadero, que no atiende sábados) DPTO. PROVINCIA DISTRITO NOMBRE DIRECCIÓN Avenida Luzuriaga N° 669 - 673 Mz. A Conjunto Comercial Ancash Huaraz Huaraz Huaraz Lote 09 Ancash Santa Chimbote Chimbote Avenida José Gálvez N° 245-250 Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Calle Nicolás de Piérola N°110 -112 Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Rivero Calle Rivero N° 107 Arequipa Arequipa Cayma Periférica Arequipa Avenida Cayma N° 618 Arequipa Arequipa José Luis Bustamante y Rivero Bustamante y Rivero Avenida Daniel Alcides Carrión N° 217A-217B Arequipa Arequipa Miraflores Miraflores Avenida Mariscal Castilla N° 618 Arequipa Camaná Camaná Camaná Jirón 28 de Julio N° 167 (Boulevard) Ayacucho Huamanga Ayacucho Ayacucho Jirón 28 de Julio N° 167 Cajamarca Cajamarca Cajamarca Cajamarca Jirón Pisagua N° 552 Cusco Cusco Cusco Cusco Esquina Avenida El Sol con Almagro s/n Cusco Cusco Wanchaq Wanchaq Avenida Tomasa Ttito Condemaita 1207 Huancavelica Huancavelica Huancavelica Huancavelica Jirón Francisco de Angulo 286 Huánuco Huánuco Huánuco Huánuco Jirón 28 de Julio N° 1061 Huánuco Leoncio Prado Rupa Rupa Tingo María Avenida Antonio Raymondi N° 179 Ica Chincha Chincha Alta Chincha Jirón Mariscal Sucre N° 141 Ica Ica Ica Ica Avenida Graú N° 161 Ica Pisco Pisco Pisco Calle San Francisco N° 155-161-167 Junín Huancayo Chilca Chilca Avenida 9 De Diciembre N° 590 Junín Huancayo El Tambo Huancayo Jirón Santiago Norero N° 462 Junín Huancayo Huancayo Periférica Huancayo Calle Real N° 517 La Libertad Trujillo Trujillo Trujillo Avenida Diego de Almagro N° 297 La Libertad Trujillo Trujillo Periférica Trujillo Avenida Manuel Vera Enríquez N° 476-480 Avenida Victor Larco Herrera N° 1243 Urbanización La La Libertad Trujillo Victor Larco Herrera Victor Larco Merced Lambayeque Chiclayo Chiclayo Chiclayo Esquina Elías Aguirre con L. -

Redalyc.Railroads in Peru: How Important Were They?

Desarrollo y Sociedad ISSN: 0120-3584 [email protected] Universidad de Los Andes Colombia Zegarra, Luis Felipe Railroads in Peru: How Important Were They? Desarrollo y Sociedad, núm. 68, diciembre, 2011, pp. 213-259 Universidad de Los Andes Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=169122461007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista 68 213 Desarrollo y Sociedad II semestre 2011 Railroads in Peru: How Important Were They? Ferrocarriles en el Perú: ¿Qué tan importantes fueron? Luis Felipe Zegarra* Abstract This paper analyzes the evolution and main features of the railway system of Peru in the 19th and early 20th centuries. From mid-19th century railroads were considered a promise for achieving progress. Several railroads were then built in Peru, especially in 1850-75 and in 1910-30. With the construction of railroads, Peruvians saved time in travelling and carrying freight. The faster service of railroads did not necessarily come at the cost of higher passenger fares and freight rates. Fares and rates were lower for railroads than for mules, especially for long distances. However, for some routes (especially for short distances with many curves), the traditional system of llamas remained as the lowest pecuniary cost (but also slowest) mode of transportation. Key words: Transportation, railroads, Peru, Latin America. JEL classification: N70, N76, R40. * Luis Felipe Zegarra is PhD in Economics of University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). -

Hydrochemical Evaluation of Changing Glacier Meltwater Contribution To

(b) Rio Santa U53A-0703 4000 Callejon de Huaylas Contour interval = 1000 m 3000 0S° Hydrochemical evaluation of changing glacier meltwater 2000 Lake Watershed Huallanca PERU 850'° 4000 Glacierized Cordillera Blanca ° Colcas Trujillo 6259 contribution to stream discharge, Callejon de Huaylas, Perú 78 00' 8S° Negra Low Cordillera Blanca Paron Chimbote SANTA LOW Llullan (a) 6395 Kinzl ° Lima 123 (c) Llanganuco 77 20' Lake Titicaca Bryan G. Mark , Jeffrey M. McKenzie and Kathy A. Welch Ranrahirca 6768 910'° Cordillera Negra 16° S 5000 La Paz 1 >4000 m in elevation 4000 Buin Department of Geography, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA,[email protected] ; 6125 80° W 72° W 3000 2 Marcara 5237 Department of Earth Sciences, Syracuse University, Syracuse New York, 13244, USA,[email protected] ; Anta 5000 Glaciar Paltay Yanamarey 3 JANGAS 6162 4800 Byrd Polar Research Center, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH 43210, USA, [email protected] YAN Quilcay 5322 5197 Huaraz 6395 4400 Q2 4800 SANTA2 (d) 4400 Olleros watershed divide4400 ° Q1 Q3 4000 ABSTRACT 77 00' Querococha Yanayacu 950'° 3980 2 Q3 The Callejon de Huaylas, Perú, is a well-populated 5000 km watershed of the upper Rio Santa river draining the glacierized Cordillera 4000 Pachacoto Lake Glacierized area Blanca. This tropical intermontane region features rich agricultural diversity and valuable natural resources, but currently receding glaciers Contour interval = 200 m 2 0 2 4km are causing concerns for future water supply. A major question concerns the relative contribution of glacier meltwater to the regional stream SETTING The Andean Cordillera Blanca of Perú is the most glacierized mountain range in the tropics. -

CLIMATE RISK COUNTRY PROFILE: GHANA Ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This Profile Is Part of a Series of Climate Risk Country Profiles Developed by the World Bank Group (WBG)

CLIMATE RISK COUNTRY PROFILE GHANA COPYRIGHT © 2021 by the World Bank Group 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of the World Bank Group (WBG) and with external contributions. The opinions, findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or the official policy or position of the WBG, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments it represents. The WBG does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work and do not make any warranty, express or implied, nor assume any liability or responsibility for any consequence of their use. This publication follows the WBG’s practice in references to member designations, borders, and maps. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work, or the use of the term “country” do not imply any judgment on the part of the WBG, its Boards, or the governments it represents, concerning the legal status of any territory or geographic area or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. The mention of any specific companies or products of manufacturers does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the WBG in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because the WBG encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. -

Multi-Source Glacial Lake Outburst Flood Hazard Assessment and Mapping for Huaraz, Cordillera Blanca, Peru

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 21 November 2018 doi: 10.3389/feart.2018.00210 Multi-Source Glacial Lake Outburst Flood Hazard Assessment and Mapping for Huaraz, Cordillera Blanca, Peru Holger Frey 1*, Christian Huggel 1, Rachel E. Chisolm 2†, Patrick Baer 1†, Brian McArdell 3, Alejo Cochachin 4 and César Portocarrero 5† 1 Department of Geography, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2 Center for Research in Water Resources, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, United States, 3 Mountain Hydrology and Mass Movements Research Unit, Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research (WSL), Birmensdorf, Switzerland, 4 Autoridad Nacional del Agua – Unidad de Glaciología y Recursos Hídricos (ANA-UGRH), Huaraz, Peru, 5 Área Glaciares, Instituto Nacional de Investigación Edited by: en Glaciares y Ecosistemas de Montaña (INAIGEM), Huaraz, Peru Davide Tiranti, Agenzia Regionale per la Protezione The Quillcay catchment in the Cordillera Blanca, Peru, contains several glacial lakes, Ambientale (ARPA), Italy including Lakes Palcacocha (with a volume of 17 × 106 m3), Tullparaju (12 × 106 m3), Reviewed by: 6 3 Dhananjay Anant Sant, and Cuchillacocha (2 × 10 m ). In 1941 an outburst of Lake Palcacocha, in one of Maharaja Sayajirao University of the deadliest historical glacial lake outburst floods (GLOF) worldwide, destroyed large Baroda, India Fabio Matano, parts of the city of Huaraz, located in the lowermost part of the catchment. Since Consiglio Nazionale Delle Ricerche this outburst, glaciers, and glacial lakes in Quillcay catchment have undergone drastic (CNR), Italy changes, including a volume increase of Lake Palcacocha between around 1990 and *Correspondence: 2010 by a factor of 34. In parallel, the population of Huaraz grew exponentially to more Holger Frey [email protected] than 120,000 inhabitants nowadays, making a comprehensive assessment and mapping of GLOF hazards for the Quillcay catchment and the city of Huaraz indispensable. -

Forms and Functions of Negation in Huaraz Quechua (Ancash, Peru): Analyzing the Interplay of Common Knowledge and Sociocultural Settings

Forms and Functions of Negation in Huaraz Quechua (Ancash, Peru): Analyzing the Interplay of Common Knowledge and Sociocultural Settings Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie am Fachbereich Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Cristina Villari aus Verona (Italien) Berlin 2017 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Michael Dürr 2. Gutachterin: Prof. Dr. Ingrid Kummels Tag der Disputation: 18.07.2017 To Ani and Leonel III Acknowledgements I wish to thank my teachers, colleagues and friends who have provided guidance, comments and encouragement through this process. I gratefully acknowledge the support received for this project from the Stiftung Lateinamerikanische Literatur. Many thanks go to my first supervisor Prof. Michael Dürr for his constructive comments and suggestions at every stage of this work. Many of his questions led to findings presented here. I am indebted to him for his precious counsel and detailed review of my drafts. Many thanks also go to my second supervisor Prof. Ingrid Kummels. She introduced me to the world of cultural anthropology during the doctoral colloquium at the Latin American Institute at the Free University of Berlin. The feedback she and my colleagues provided was instrumental in composing the sociolinguistic part of this work. I owe enormous gratitude to Leonel Menacho López and Anita Julca de Menacho. In fact, this project would not have been possible without their invaluable advice. During these years of research they have been more than consultants; Quechua teachers, comrades, guides and friends. With Leonel I have discussed most of the examples presented in this dissertation. It is only thanks to his contributions that I was able to explain nuances of meanings and the cultural background of the different expressions presented. -

Avance De La Implementación

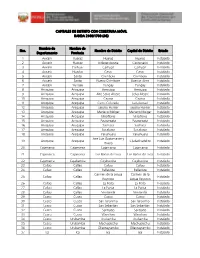

CAPITALES DE DISTRITO CON COBERTURA MÓVIL BANDA 2100/1700 (4G) Nombre de Nombre de Nro. Nombre de Distrito Capital de Distrito Estado Departamento Provincia 1 Ancash Huaraz Huaraz Huaraz Instalado 2 Ancash Huaraz Independencia Centenario Instalado 3 Ancash Carhuaz Carhuaz Carhuaz Instalado 4 Ancash Huaylas Caraz Caraz Instalado 5 Ancash Santa Chimbote Chimbote Instalado 6 Ancash Santa Nuevo Chimbote Buenos Aires Instalado 7 Ancash Yungay Yungay Yungay Instalado 8 Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Arequipa Instalado 9 Arequipa Arequipa Alto Selva Alegre Selva Alegre Instalado 10 Arequipa Arequipa Cayma Cayma Instalado 11 Arequipa Arequipa Cerro Colorado La Libertad Instalado 12 Arequipa Arequipa Jacobo Hunter Jacobo Hunter Instalado 13 Arequipa Arequipa Mariano Melgar Mariano Melgar Instalado 14 Arequipa Arequipa Miraflores Miraflores Instalado 15 Arequipa Arequipa Paucarpata Paucarpata Instalado 16 Arequipa Arequipa Sachaca Sachaca Instalado 17 Arequipa Arequipa Socabaya Socabaya Instalado 18 Arequipa Arequipa Yanahuara Yanahuara Instalado Jose Luis Bustamante y 19 Arequipa Arequipa Ciudad Satelite Instalado Rivero 20 Cajamarca Cajamarca Cajamarca Cajamarca Instalado 21 Cajamarca Cajamarca Los Baños del Inca Los Baños del Inca Instalado 22 Cajamarca Cajabamba Cajabamba Cajabamba Instalado 23 Callao Callao Callao Callao Instalado 24 Callao Callao Bellavista Bellavista Instalado Carmen de la Legua Carmen de la 25 Callao Callao Instalado Reynoso Legua Reynoso 26 Callao Callao La Perla La Perla Instalado 27 Callao Callao La Punta La Punta Instalado 28 Callao Callao Ventanilla Ventanilla Instalado 29 Cusco Cusco Cusco Cusco Instalado 30 Cusco Cusco San Jeronimo San Jeronimo Instalado 31 Cusco Cusco San Sebastian San Sebastian Instalado 32 Cusco Cusco Santiago Santiago Instalado 33 Cusco Cusco Wanchaq Wanchaq Instalado 34 Cusco Urubamba Urubamba Urubamba Instalado 35 Cusco Urubamba Machupicchu Machupicchu Instalado 36 Cusco Urubamba Ollantaytambo Ollantaytambo Instalado 37 Ica Ica Ica Ica Instalado Nombre de Nombre de Nro. -

Climate Change Guidelines for Forest Managers for Forest Managers

0.62cm spine for 124 pg on 90g ecological paper ISSN 0258-6150 FAO 172 FORESTRY 172 PAPER FAO FORESTRY PAPER 172 Climate change guidelines Climate change guidelines for forest managers for forest managers The effects of climate change and climate variability on forest ecosystems are evident around the world and Climate change guidelines for forest managers further impacts are unavoidable, at least in the short to medium term. Addressing the challenges posed by climate change will require adjustments to forest policies, management plans and practices. These guidelines have been prepared to assist forest managers to better assess and respond to climate change challenges and opportunities at the forest management unit level. The actions they propose are relevant to all kinds of forest managers – such as individual forest owners, private forest enterprises, public-sector agencies, indigenous groups and community forest organizations. They are applicable in all forest types and regions and for all management objectives. Forest managers will find guidance on the issues they should consider in assessing climate change vulnerability, risk and mitigation options, and a set of actions they can undertake to help adapt to and mitigate climate change. Forest managers will also find advice on the additional monitoring and evaluation they may need to undertake in their forests in the face of climate change. This document complements a set of guidelines prepared by FAO in 2010 to support policy-makers in integrating climate change concerns into new or -

Hedging Climate Risk Mats Andersson, Patrick Bolton, and Frédéric Samama

AHEAD OF PRINT Financial Analysts Journal Volume 72 · Number 3 ©2016 CFA Institute PERSPECTIVES Hedging Climate Risk Mats Andersson, Patrick Bolton, and Frédéric Samama We present a simple dynamic investment strategy that allows long-term passive investors to hedge climate risk without sacrificing financial returns. We illustrate how the tracking error can be virtually eliminated even for a low-carbon index with 50% less carbon footprint than its benchmark. By investing in such a decarbonized index, investors in effect are holding a “free option on carbon.” As long as climate change mitigation actions are pending, the low-carbon index obtains the same return as the benchmark index; but once carbon dioxide emissions are priced, or expected to be priced, the low-carbon index should start to outperform the benchmark. hether or not one agrees with the scientific the climate change debate is not yet fully settled and consensus on climate change, both climate that climate change mitigation may not require urgent Wrisk and climate change mitigation policy attention. The third consideration is that although the risk are worth hedging. The evidence on rising global scientific evidence on the link between carbon dioxide average temperatures has been the subject of recent (CO2) emissions and the greenhouse effect is over- debates, especially in light of the apparent slowdown whelming, there is considerable uncertainty regarding in global warming over 1998–2014.1 The perceived the rate of increase in average temperatures over the slowdown has confirmed the beliefs of climate change next 20 or 30 years and the effects on climate change. doubters and fueled a debate on climate science There is also considerable uncertainty regarding the widely covered by the media. -

Climate Change Scenario Report

2020 CLIMATE CHANGE SCENARIO REPORT WWW.SUSTAINABILITY.FORD.COM FORD’S CLIMATE CHANGE PRODUCTS, OPERATIONS: CLIMATE SCENARIO SERVICES AND FORD FACILITIES PUBLIC 2 Climate Change Scenario Report 2020 STRATEGY PLANNING TRUST EXPERIENCES AND SUPPLIERS POLICY CONCLUSION ABOUT THIS REPORT In conjunction with our annual sustainability report, this Climate Change CONTENTS Scenario Report is intended to provide stakeholders with our perspective 3 Ford’s Climate Strategy on the risks and opportunities around climate change and our transition to a low-carbon economy. It addresses details of Ford’s vision of the low-carbon 5 Climate Change Scenario Planning future, as well as strategies that will be important in managing climate risk. 11 Business Strategy for a Changing World This is Ford’s second climate change scenario report. In this report we use 12 Trust the scenarios previously developed, while further discussing how we use scenario analysis and its relation to our carbon reduction goals. Based on 13 Products, Services and Experiences stakeholder feedback, we have included physical risk analysis, additional 16 Operations: Ford Facilities detail on our electrification plan, and policy engagement. and Suppliers 19 Public Policy This report is intended to supplement our first report, as well as our Sustainability Report, and does not attempt to cover the same ground. 20 Conclusion A summary of the scenarios is in this report for the reader’s convenience. An explanation of how they were developed, and additional strategies Ford is using to address climate change can be found in our first report. SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS Through our climate change scenario planning we are contributing to SDG 6 Clean water and sanitation, SDG 7 Affordable and clean energy, SDG 9 Industry, innovation and infrastructure and SDG 13 Climate action. -

Puntos De Recaudo Pagoefectivo En Agentes Kasnet - Provincia

Puntos de Recaudo PagoEfectivo en Agentes Kasnet - Provincia Departamento Provincia Distrito Localidad Nombre del Comercio Dirección Referencia AMAZONAS BAGUA COPALLIN COPALLIN BOTICA JC FARMA FRANCISCO BOLOGNESI 533 MEDIA CUADRA DEL MERCADO AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA BAGUA BAZAR LOCUTORIO ANGELICA JR. COMERCIO 524 FRENTE A PARQUE PRINCIPAL AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA BAGUA BOTICA SANIDAD J&S JR. RODRIGUEZ DE MENDOZA 442 ENTRE LA PLAZA PRINCIPAL Y EL BANCO DE LA NACION AMAZONAS BAGUA LA PECA LA PECA TELECOMUNICACIONES LURVI JR. LIMA PT. INT. 3 MERCADO LA PARADA AMAZONAS BONGARA FLORIDA FLORIDA MULTISERVICIOS J & G AV. MARGINAL S/N CD 2 FRENTE A CAJA PIURA Y A DOS CUADRAS DE COMISARIA AMAZONAS CHACHAPOYAS CHACHAPOYAS CHACHAPOYAS COSELVI JR. SALAMANCA 900 A CUADRA Y MEDIA DE LA PLAZA DE ARMAS AMAZONAS UTCUBAMBA BAGUA GRANDE BAGUA GRANDE LOCUTORIO MOVITEL PARADA MUNICIPAL PUESTO 14 FRENTE A FERRETERIA CHAVEZ AV MARIANO MELGAR AMAZONAS UTCUBAMBA BAGUA GRANDE BAGUA GRANDE MOTO REPUESTOS MENDOZA AV. CHACHAPOYAS N. 1688 FRENTE A LA UGEL BAGUA GRANDE AMAZONAS UTCUBAMBA BAGUA GRANDE BAGUA GRANDE TELECOMUNICACIONES & SERVICIOS SFA AV. CHACHAPOYAS 2294 COST. COOP. CRISTO DE BAGAZAN ANCASH CARHUAZ CARHUAZ CARHUAZ MULTISERTEL G Y M AV. PROGRESO 684 ESQUINA PLAZA DE ARMAS ANCASH CASMA CASMA CASMA JAVELI OFFICE SCHOOL AV. NEPEÑA MZ. B LT. 1 FRENTE AL BANCO DE LA NACION ANCASH HUARAZ HUARAZ HUARAZ COMPEX PERU AV. FITZCARRAL 304 ESQUINA CON JR. CARAZ ANCASH HUARAZ HUARAZ HUARAZ COMPUNET JR. JUAN DE LA CRUZ ROMERO 451 FRENTE AL MERCADO CENTRAL ANCASH HUARAZ HUARAZ HUARAZ ENKANTOS BOUTIQUE JR JULIAN DE MORALES 709 FRENTE A LA FACULTAD DE MINAS ANCASH HUARAZ HUARAZ HUARAZ IMPORTACIONES TINA JR JOSE DE SAN MARTIN 571 A MEDIA CUADRA DEL PARQUEO ANCASH HUARAZ HUARAZ HUARAZ INVERSIONES DENNYS JR. -

Human Mobility and the Paris Agreement: Contribution of Climate Policy to the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migr

Human mobility and the Paris Agreement: Contribution of climate policy to the global compact for safe, orderly and regular migration Input to the UN Secretary-General’s report on the global compact for safe, orderly and regular migration, in response to Note Verbale of 21 July 2017, requesting inputs to the Secretary-General’s report on the global compact for safe, orderly and regular migration Koko Warner, Manager of the Impacts, Vulnerabilities and Risks subprogramme, UN Climate Secretariat (UNFCCC) Bonn, 19 September 2017 Contents 1. Introduction: Climate policy aims to safeguard resilience ................................................................... 1 2. Human mobility under the UNFCCC process including the Paris Agreement....................................... 2 3. Conclusions: Paris Agreement provides scope of climate impacts affecting future human mobility .. 3 1. Introduction: Climate policy aims to safeguard resilience Helping countries bolster resilience in the face of climatic risks – the ability to rise again when climatic disruptions pose stumbling blocks to sustainable development and food production – is a foundational part of climate policy. The topic of migration, displacement, and planned relocation, introduced in international climate policy in 2010, is framed as a climate risk management issue in the context of a “resilience continuum”. The work on climate impacts, vulnerabilities, and risks puts human mobility in the context of preempting, planning for, managing and having contingency arrangements to aid society