There Is No Escape: Theatricality in Hades

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loeb Lucian Vol5.Pdf

THE LOEB CLASSICAL LIBRARY FOUNDED BY JAMES LOEB, LL.D. EDITED BY fT. E. PAGE, C.H., LITT.D. litt.d. tE. CAPPS, PH.D., LL.D. tW. H. D. ROUSE, f.e.hist.soc. L. A. POST, L.H.D. E. H. WARMINGTON, m.a., LUCIAN V •^ LUCIAN WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY A. M. HARMON OK YALE UNIVERSITY IN EIGHT VOLUMES V LONDON WILLIAM HEINEMANN LTD CAMBRIDGE, MASSACHUSETTS HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS MOMLXII f /. ! n ^1 First printed 1936 Reprinted 1955, 1962 Printed in Great Britain CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF LTTCIAN'S WORKS vii PREFATOEY NOTE xi THE PASSING OF PEBEORiNUS (Peregrinus) .... 1 THE RUNAWAYS {FugiUvt) 53 TOXARis, OR FRIENDSHIP (ToxaHs vd amiciHa) . 101 THE DANCE {Saltalio) 209 • LEXiPHANES (Lexiphanes) 291 THE EUNUCH (Eunuchiis) 329 ASTROLOGY {Astrologio) 347 THE MISTAKEN CRITIC {Pseudologista) 371 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE GODS {Deorutti concilhim) . 417 THE TYRANNICIDE (Tyrannicidj,) 443 DISOWNED (Abdicatvs) 475 INDEX 527 —A LIST OF LUCIAN'S WORKS SHOWING THEIR DIVISION INTO VOLUMES IN THIS EDITION Volume I Phalaris I and II—Hippias or the Bath—Dionysus Heracles—Amber or The Swans—The Fly—Nigrinus Demonax—The Hall—My Native Land—Octogenarians— True Story I and II—Slander—The Consonants at Law—The Carousal or The Lapiths. Volume II The Downward Journey or The Tyrant—Zeus Catechized —Zeus Rants—The Dream or The Cock—Prometheus—* Icaromenippus or The Sky-man—Timon or The Misanthrope —Charon or The Inspector—Philosophies for Sale. Volume HI The Dead Come to Life or The Fisherman—The Double Indictment or Trials by Jury—On Sacrifices—The Ignorant Book Collector—The Dream or Lucian's Career—The Parasite —The Lover of Lies—The Judgement of the Goddesses—On Salaried Posts in Great Houses. -

Iron Within, Iron Without

BACKLIST Book 1 – HORUS RISING Book 2 – FALSE GODS Book 3 – GALAXY IN FLAMES Book 4 – THE FLIGHT OF THE EISENSTEIN Book 5 – FULGRIM Book 6 – DESCENT OF ANGELS Book 7 – LEGION Book 8 – BATTLE FOR THE ABYSS Book 9 – MECHANICUM Book 10 – TALES OF HERESY Book 11 – FALLEN ANGELS Book 12 – A THOUSAND SONS Book 13 – NEMESIS Book 14 – THE FIRST HERETIC Book 15 – PROSPERO BURNS Book 16 – AGE OF DARKNESS Book 17 – THE OUTCAST DEAD Book 18 – DELIVERANCE LOST Book 19 – KNOW NO FEAR Book 20 – THE PRIMARCHS Book 21 – FEAR TO TREAD Book 22 – SHADOWS OF TREACHERY Book 23 – ANGEL EXTERMINATUS Book 24 – BETRAYER Book 25 – MARK OF CALTH Book 26 – VULKAN LIVES Book 27 – THE UNREMEMBERED EMPIRE Book 28 – SCARS Book 29 – VENGEFUL SPIRIT Book 30 – THE DAMNATION OF PYTHOS Book 31 – LEGACIES OF BETRAYAL Book 32 – DEATHFIRE Book 33 – WAR WITHOUT END Book 34 – PHAROS Book 35 – EYE OF TERRA Book 36 – THE PATH OF HEAVEN Book 37 – THE SILENT WAR Book 38 – ANGELS OF CALIBAN Book 39 – PRAETORIAN OF DORN Book 40 – CORAX Book 41 – THE MASTER OF MANKIND Book 42 – GARRO Book 43 – SHATTERED LEGIONS Book 44 – THE CRIMSON KING Book 45 – TALLARN Book 46 – RUINSTORM Book 47 – OLD EARTH Book 48 – THE BURDEN OF LOYALTY Book 49 – WOLFSBANE Book 50 – BORN OF FLAME Book 51 – SLAVES TO DARKNESS Book 52 – HERALDS OF THE SIEGE More tales from the Horus Heresy... PROMETHEAN SUN AURELIAN BROTHERHOOD OF THE STORM THE CRIMSON FIST CORAX: SOULFORGE PRINCE OF CROWS DEATH AND DEFIANCE TALLARN: EXECUTIONER SCORCHED EARTH THE PURGE THE HONOURED THE UNBURDENED BLADES OF THE TRAITOR TALLARN: IRONCLAD RAVENLORD THE SEVENTH SERPENT WOLF KING CYBERNETICA SONS OF THE FORGE Many of these titles are also available as abridged and unabridged audiobooks. -

Songs of the Last Philosopher: Early Nietzsche and the Spirit of Hölderlin

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2013 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2013 Songs of the Last Philosopher: Early Nietzsche and the Spirit of Hölderlin Sylvia Mae Gorelick Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2013 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Recommended Citation Gorelick, Sylvia Mae, "Songs of the Last Philosopher: Early Nietzsche and the Spirit of Hölderlin" (2013). Senior Projects Spring 2013. 318. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2013/318 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Songs of the Last Philosopher: Early Nietzsche and the Spirit of Hölderlin Senior Project submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Sylvia Mae Gorelick Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 1, 2013 For Thomas Bartscherer, who agreed at a late moment to join in the struggle of this infinite project and who assisted me greatly, at times bringing me back to earth when I flew into the meteoric heights of Nietzsche and Hölderlin’s songs and at times allowing me to soar there. -

Black Orpheus, Myth and Ritual: a Morphological Reading*

DOI 10.1007/s12138-008-0009-y Black Orpheus, Myth and Ritual: A Morphological Reading* HARDY FREDRICKSMEYER # Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2008 Black Orpheus (Orfeu Negro; M. Camus, 1959) drew on classical myth and ritual to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival and the Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Yet no one has analyzed the film with reference to its classical background. This paper argues that the film closely follows two narrative patterns (Separation-Liminality- Incorporation and the Heroic Journey) employed by the myth of Orpheus and Eury- dice, and related stories. This morphological approach reveals the cinematic Euridice as a “female adolescent initiand” whose loss of virginity and death are foreshadowed from her first scene. The film’s setting of Carnaval promotes Euridice’s adolescent ini- tiation as it duplicates ancient Greek Dionysian festivals. Orfeu emerges as not only a shamanistic hero, but also an associate of Apollo and, antithetically, an avatar of Diony- sus and substitute sacrifice for the god. Finally, the film not only replicates but also reinvents the ancient, rural and European myth of Orpheus and Eurydice by resituat- ing it in a modern city of the Africanized “New World.” A Stephanie, la compagna della mia vita lack Orpheus (Orfeu Negro; M. Camus, 1959) explodes on the screen as a Bsensual tour de force of color, music and dance, all framed by the rhapsodic beauty of Rio de Janeiro during Carnaval. Critical and popular admiration for these audio-visual qualities help to explain why Black Orpheus won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival, and the Oscar for Best Foreign Film, and why it remains one of the most successful films of all time with a Latin-Amer- * For their thoughtful comments on earlier versions of this essay, I would like to thank the editor of this journal, Wolfgang Haase, the anonymous referees, Erwin Cook, John Gibert, Ernst Fredricksmeyer, and Donald Wilkerson. -

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who This article is about the television series. For other uses, see Doctor Who (disambiguation). Doctor Who Genre Science fiction drama Created by • Sydney Newman • C. E. Webber • Donald Wilson Written by Various Directed by Various Starring Various Doctors (as of 2014, Peter Capaldi) Various companions (as of 2014, Jenna Coleman) Theme music composer • Ron Grainer • Delia Derbyshire Opening theme Doctor Who theme music Composer(s) Various composers (as of 2005, Murray Gold) Country of origin United Kingdom No. of seasons 26 (1963–89) plus one TV film (1996) No. of series 7 (2005–present) No. of episodes 800 (97 missing) (List of episodes) Production Executive producer(s) Various (as of 2014, Steven Moffat and Brian Minchin) Camera setup Single/multiple-camera hybrid Running time Regular episodes: • 25 minutes (1963–84, 1986–89) • 45 minutes (1985, 2005–present) Specials: Various: 50–75 minutes Broadcast Original channel BBC One (1963–1989, 1996, 2005–present) BBC One HD (2010–present) BBC HD (2007–10) Picture format • 405-line Black-and-white (1963–67) • 625-line Black-and-white (1968–69) • 625-line PAL (1970–89) • 525-line NTSC (1996) • 576i 16:9 DTV (2005–08) • 1080i HDTV (2009–present) Doctor Who 2 Audio format Monaural (1963–87) Stereo (1988–89; 1996; 2005–08) 5.1 Surround Sound (2009–present) Original run Classic series: 23 November 1963 – 6 December 1989 Television film: 12 May 1996 Revived series: 26 March 2005 – present Chronology Related shows • K-9 and Company (1981) • Torchwood (2006–11) • The Sarah Jane Adventures (2007–11) • K-9 (2009–10) • Doctor Who Confidential (2005–11) • Totally Doctor Who (2006–07) External links [1] Doctor Who at the BBC Doctor Who is a British science-fiction television programme produced by the BBC. -

The Project Gutenberg's Etext Myth, Ritual, and Religion, Vol. 1 #28 in Our Series by Andrew Lang

The Project Gutenberg's Etext Myth, Ritual, and Religion, Vol. 1 #28 in our series by Andrew Lang Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. *It must legally be the first thing seen when opening the book.* In fact, our legal advisors said we can't even change margins. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. Title: Myth, Ritual, and Religion, Vol. 1 Author: Andrew Lang September, 2001 [Etext #2832] The Project Gutenberg Etext of Myth, Ritual, and Religion, Vol. 1 *******This file should be named 1mrar10.txt or 1mrar10.zip****** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, 1mrar11.txt VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, 1mrar10a.txt This etext was prepared by Donald Lainson, [email protected]. Project Gutenberg Etexts are usually created from multiple editions, all of which are in the Public Domain in the United States, unless a copyright notice is included. Therefore, we usually do NOT keep any of these books in compliance with any particular paper edition. We are now trying to release all our books one month in advance of the official release dates, leaving time for better editing. -

Doctor Who Assistants

COMPANIONS FIFTY YEARS OF DOCTOR WHO ASSISTANTS An unofficial non-fiction reference book based on the BBC television programme Doctor Who Andy Frankham-Allen CANDY JAR BOOKS . CARDIFF A Chaloner & Russell Company 2013 The right of Andy Frankham-Allen to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Copyright © Andy Frankham-Allen 2013 Additional material: Richard Kelly Editor: Shaun Russell Assistant Editors: Hayley Cox & Justin Chaloner Doctor Who is © British Broadcasting Corporation, 1963, 2013. Published by Candy Jar Books 113-116 Bute Street, Cardiff Bay, CF10 5EQ www.candyjarbooks.co.uk A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted at any time or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the copyright holder. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise be circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. Dedicated to the memory of... Jacqueline Hill Adrienne Hill Michael Craze Caroline John Elisabeth Sladen Mary Tamm and Nicholas Courtney Companions forever gone, but always remembered. ‘I only take the best.’ The Doctor (The Long Game) Foreword hen I was very young I fell in love with Doctor Who – it Wwas a series that ‘spoke’ to me unlike anything else I had ever seen. -

Against Expression: an Anthology of Conceptual Writing

Against Expression Against Expression An Anthology of Conceptual Writing E D I T E D B Y C R A I G D W O R K I N A N D KENNETH GOLDSMITH Northwestern University Press Evanston Illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © by Northwestern University Press. Published . All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America + e editors and the publisher have made every reasonable eff ort to contact the copyright holders to obtain permission to use the material reprinted in this book. Acknowledgments are printed starting on page . Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Against expression : an anthology of conceptual writing / edited by Craig Dworkin and Kenneth Goldsmith. p. cm. — (Avant- garde and modernism collection) Includes bibliographical references. ---- (pbk. : alk. paper) . Literature, Experimental. Literature, Modern—th century. Literature, Modern—st century. Experimental poetry. Conceptual art. I. Dworkin, Craig Douglas. II. Goldsmith, Kenneth. .A .—dc o + e paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, .-. To Marjorie Perlo! Contents Why Conceptual Writing? Why Now? xvii Kenneth Goldsmith + e Fate of Echo, xxiii Craig Dworkin Monica Aasprong, from Soldatmarkedet Walter Abish, from Skin Deep Vito Acconci, from Contacts/ Contexts (Frame of Reference): Ten Pages of Reading Roget’s ! esaurus from Removal, Move (Line of Evidence): + e Grid Locations of Streets, Alphabetized, Hagstrom’s Maps of the Five Boroughs: . Manhattan Kathy Acker, from Great Expectations Sally Alatalo, from Unforeseen Alliances Paal Bjelke Andersen, from + e Grefsen Address Anonymous, Eroticism David Antin, A List of the Delusions of the Insane: What + ey Are Afraid Of from Novel Poem from + e Separation Meditations Louis Aragon, Suicide Nathan Austin, from Survey Says! J. -

Low-Resolution Bandwidth-Friendly

The Sixth Doctor Expanded Universe Sourcebook is a not-for-sale, not-for-profit, unofficial and unapproved fan-made production First edition published August 2018 Full credits at the back Doctor Who: Adventures in Time and Space RPG and Cubicle 7 logo copyright Cubicle 7 Entertainment Ltd. 2013 BBC, DOCTOR WHO, TARDIS and DALEKS are trademarks of the British Broadcasting Corporation All material belongs to its authors (BBC, Virgin, Big Finish, etc.) No attack on such copyrights are intended, nor should be perceived. Please seek out the original source material, you’ll be glad you did. And look for more Doctor Who Expanded Universe Sourcebooks at www.siskoid.com/ExpandedWho including versions of this sourcebook in both low (bandwidth-friendly) and high (print-quality) formats Introduction 4 Prince Most-Deepest-All-Yellow A66 Chapter 1: Sixth Doctor’s Expanded Timeline 5 Professor Pierre Aronnax A67 Professor Rummas A68 Chapter 2: Companions and Allies Rob Roy MacGregor A69 Angela Jennings A1 Rossiter A70 Charlotte Pollard A2 Salim Jahangir A71 Colonel Emily Chaudhry A3 Samuel Belfrage A72 Constance Clarke A4 Sebastian Malvern A73 Dr Peri Brown A5 Sir Walter Raleigh A74 Evelyn Smythe A6 Tegoya Azzuron A75 Flip Jackson A7 The Temporal Powers A76 Frobisher A8 Toby the Sapient Pig A77 Grant Markham A9 Trey Korte A79 Jamie McCrimmon A10 Winston Churchill A80 Jason and Crystal (and Zog) A11 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart A81 Lieutenant Will Hoffman A13 Mathew Sharpe A14 Chapter 3: Monsters and Villains Melaphyre, The Technomancer A15 Adolf Hitler V1 -

Fish Fingers and Custard Issue 2 Where Do You Go When All the Love Has Gone?

Fish Fingers and Custard Issue 2 Where Do You Go When All The Love Has Gone? Those are lyrics that I have just made up. I’m sure you’ll agree that I’m up there with all the modern musical geniuses, such as Prince, Stevie Wonder, Eric Clapton and Justin Bieber. But where am I going with this? I have an idea and it WILL make sense. Or so I hope… The beauty with Doctor Who is that even when the 13 weeks worth of episodes have gone, we don’t need to cry and mourn for its disappearance (or in my case – ran off without a word and never contacted me again). There are all sorts of commodities out there that we can lay our hands on and enjoy. (I’m starting to regret making this analogy now, as the drug-crazed aliens from Torchwood: Children of Earth would have been a better comparison!) The sheer size of Doctor Who fandom is incredibly huge and you’ll always be able to pick up something that’ll make you feel the way you do when you’re stuck in the middle of an episode. (This fanzine is akin to Love and Monsters than Empty Child/The Doctor Dances, to be honest!) Whether it be a magazine, book, DVD, audiobook, toy (they ARE toys btw), convention, podcast or even a fanzine, it’s all out there for us to explore and enjoy when a series ends, so we’ve no need to get upset and pine until Christmas! And wasn’t Series 5 (or whatever you want to call it) just superb? I can be quite smug here and say that I was never worried about Matt Smith nailing the role of The Doctor. -

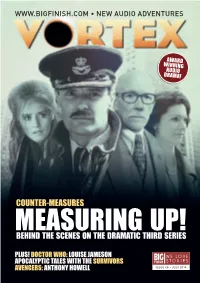

Measuringbehind the Scenes on the Dramatic Third Up! Series

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES AWARD WINNING AUDIO DRAMA! COUNTER-MEASURES MEASURINGBEHIND THE SCENES ON THE DRAMATIC THIRD UP! SERIES PLUS! DOCTOR WHO: LOUISE JAMESON APOCALYPTIC TALES WITH THE SURVIVORS AVENGERS: ANTHONY HOWELL ISSUE 65 • JULY 2014 VORTEX PAGE 1 VORTEX PAGE 2 WELCOME TO BIG FINISH! WE LOVE STORIES AND WE MAKE GREAT FULL-CAST AUDIO DRAMA AND AUDIOBOOKS YOU CAN BUY ON CD AND/OR DOWNLOAD Our audio productions are based on much- You can access a video guide to the site by loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark Shadows, clicking here. Blake’s 7, Stargate and Highlander as well as classic characters such as Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless and The SUBSCRIBERS GET MORE AT Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. BIGFINISH.COM! If you subscribe, depending on the range you We publish a growing number of books (non- subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs fiction, novels and short stories) from new and of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a established authors. bonus release and discounts. WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH /THEBIGFINISH VORTEX PAGE 3 VORTEX PAGE 4 SNEAK PREVIEWS EDITORIAL AND WHISPERS DOCTOR WHO – THE ROMANCE ELLO! I’m Kenny, and I’ve kindly been invited by Big Finish to OF CRIME AND THE ENGLISH succeed the late, great Paul Spragg as editor of Vortex. WAY OF DEATH H Don’t fear if you think that Big Finish have allowed Vortex to fall into the hands of someone who has no idea of what the company is all about. -

The Two Babylons – Alexander Hislop

The Two Babylon’s Alexander Hislop Table of Contents Introduction Chapter I Distinctive Character of the Two Systems Chapter II Objects of Worship Section I. Trinity in Unity Section II. The Mother and Child, and the Original of the Child Sub-Section I. The Child in Assyria Sub-Section II. The Child in Egypt Sub-Section III. The Child in Greece Sub-Section IV. The Death of the Child Sub-Section V. The Deification of the Child Section III. The Mother of the Child Chapter III Festivals Section I. Christmas and Lady-day Section II. Easter Section III. The Nativity of St. John Section IV. The Feast of the Assumption Chapter IV Doctrine and Discipline Section I. Baptismal Regeneration Section II. Justification by Works Section III. The Sacrifice of the Mass Section IV. Extreme Unction Section V. Purgatory and Prayers for the Dead Chapter V Rites and Ceremonies Section I. Idol Procession (15k) Section II. Relic Worship (16k) Section III. The Clothing and Crowning of Images Section IV. The Rosary and the Worship of the Sacred Heart Section V. Lamps and Wax-Candles Section VI. The Sign of the Cross Chapter VI Religious Orders Section I. The Sovereign Pontiff Section II. Priests, Monks, and Nuns Chapter VII The Two Developments Historically and Prophetically Considered Section I. The Great Red Dragon Section II. The Beast from the Sea Section III. The Beast from the Earth The Two Babylons – Alexander Hislop Section IV. The Image of the Beast Section V. The Name of the Beast, the Number of His Name— Invisible Head of the Papacy Conclusion 2 The Two Babylons – Alexander Hislop Introduction "And upon her forehead was a name written, MYSTERY, BABYLON THE GREAT, THE MOTHER OF HARLOTS AND ABOMINATIONS OF THE EARTH."--Revelation 17:5 There is this great difference between the works of men and the works of God, that the same minute and searching investigation, which displays the defects and imperfections of the one, brings out also the beauties of the other.