Folk-Songs Comprised in the Finnish Kalevala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visits to Tuonela Ne of the Many Mythologies Which Have Had an In

ne of the many mythologies which have had an in fluence on Tolkien's work was the Kalevala, the 22000- line poem recounting the adventures of a group of Fin nish heroes. It has many characteristics peculiar to itself and is quite different from, for example, Greek or Germanic mythology. It would take too long to dis cuss this difference, but the prominent role of women (particularly mothers) throughout the book may be no ted, as well as the fact that the heroes and the style are 'low-brow', as Tolkien described them, as opposed to the 'high-brow' heroes common in other mytholog- les visits to Tuonela (Hades) are fairly frequent; and magic and shape-change- ing play a large part in the epic. Another notable feature which the Kaleva la shares with QS is that it is a collection of separate, but interrelated, tales of heroes, with the central theme of war against Pohjola, the dreary North, running through the whole epic, and individual themes in the separate tales. However, it must be appreciated that QS, despite the many influences clearly traceable behind it, is, as Carpenter reminds us, essentially origin al; influences are subtle, and often similar incidents may occur in both books, but be employed in different circumstances, or be used in QS simply as a ba sis for a tale which Tolkien would elaborate on and change. Ibis is notice able even in the tale of Turin (based on the tale of Kullervo), in which the Finnish influence is strongest. I will give a brief synopsis of the Kullervo tale, to show that although Tolkien used the story, he varied it, added to it, changed its style (which cannot really be appreciated without reading the or iginal ), and moulded it to his own use. -

Mythological Archetypes in the Legendarium of J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K

Mythological archetypes in the Legendarium of J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series Anu Vehkomäki Master’s thesis English Faculty of Humanities University of Oulu Autumn 2020 Table of contents Abstract 1. Introduction ………………………….………………………………… 4 2. Materials used ………………………………………...……………….. 6 3. Theory and Methodology …………………………………….……….. 8 3.1. Critique of Jung’s Theory…………………………………………….. 9 3.2. Terminology…………….…………………………………………….. 13 3.2.1. Myth, Mythology and Fairy Tale ………………………………… 13 3.2.2. Religion and Mythology in Tolkien’s Works …………………….. 14 4. Mythical Archetypes in Tolkien’s Works ……………………………... 17 4.1. Wise Men ……………………………………………………………... 17 4.2. Tricksters …..…………………………………………………………. 20 4.3. Heroes ………………………………………………………………… 24 4.4. Evil ……………………………………………………………………. 30 4.5. Mother ………………………………………………………………… 38 4.6. Shadow ………………………………………………………………… 43 5. Mythological Archetypes in Harry Potter Series ………………………. 49 5.1. Wise Men ……………………………………………………………… 49 5.2. Tricksters.……………………………………………………………… 51 5.3. Heroes …………………………………………………………………. 54 5.4. Evil ……………………………………………………………………. 56 5.5. Mother ………………………………………………………………… 57 6. Conclusion ……………………………………………………………... 64 Works cited 2 Abstract This thesis introduces mythical archetypes in J.R.R. Tolkien and J.K. Rowling’s works. Tolkien’s legendarium is filled with various elements from other mythologies and if read side by side many points in which these myths cross with paths with his creations can be found. In this thesis Tolkien’s works represent the literary myth. Rowling’s Harry Potter series is a fantasy series targeted to children without the same level of mythology attached. High fantasy represented by Tolkien is known for being myth like in its nature. Tolkien has stated in Letter 131 that he wanted to create a mythology for England and knowingly borrowed elements from world’s mythologies and adapted them to his own writing. -

Helgenforteljingane Si Rolle I Tidleg Jødedom, Kristendom Og Islam

Det velges mellom: RELV202/302 The Religions and Mythologies of the Baltic Finns og RELV202/302: Hagiografiar - Helgenforteljingane si rolle i tidleg jødedom, kristendom og islam RELV202/302 The Religions and Mythologies of the Baltic Finns Course literature Books (can be borrowed at the University Library or bought by the student) The Kalevala (Oxford World’s Classics). Translated by Keith Bosley. Oxford 2009: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-53886-7. Or a translation of the Kalevala into your own language; some examples: Kalevala [Danish]. [Transl. by] Ferdinand Ohrt. Copenhagen 1985 and later: Reitzel. Le Kalevala [French]. [Transl. by] Gabriel Rebourcet. Paris 2010: Gallimard, coll. Quarto. Kalevala [German]. [Transl. by] Lore Fromm & Hans Fromm. Wiesbaden 2005: Marix Verlag. Kalevala [Norwegian]. [Transl. by] Albert Lange Fliflet. Oslo 1999: Aschehoug. El Kalevala [Spanish]. [Transl. by] juan Bautista Bergua. Madrid 1999: Ediciones Ibéricas. Kalevala [Swedish]. [Transl. by] Lars Huldén & Mats Huldén. Stockholm 2018: Atlantis. (For a full list of translations, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Kalevala_translations) NB! Only songs 1–15, 39–49. Pentikäinen, Juha. 1999. Kalevala Mythology. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33661-9 (pbk). 296 pp. Siikala, Anna-Leena. 2002. Mythic Images and Shamanism: A Perspective on Kalevala Poetry. Helsinki: Suomalainen tiedeakademia / Finnish Academy of Science and Letters. ISBN 951-41-0902-3 (pbk). 423 pp. Book chapters – can be ordered from litteraturkiosken.uib Finnish Folk Poetry-Epic: An Anthology in Finnish and English (Publications of the Finnish Literature Society 329). Helsinki 1977: Finnish Literature Society. ISBN 951-717-087-4. Only the following pages: 83–92 (Creation), 98 (Smith), 102–109 (Singing match), 183–190 (The spell), 191–195 (Tuonela), 195–199 (Sun and moon), 212–220 (Lemminkäinen), 281–282 (Lähtö), 315–320 (St. -

Finnish Studies

Journal of Finnish Studies Volume 23 Number 1 November 2019 ISSN 1206-6516 ISBN 978-1-7328298-1-7 JOURNAL OF FINNISH STUDIES EDITORIAL AND BUSINESS OFFICE Journal of Finnish Studies, Department of English, 1901 University Avenue, Evans 458, Box 2146, Sam Houston State University, Huntsville, TEXAS 77341-2146, USA Tel. 1.936.294.1420; Fax 1.936.294.1408 E-mail: [email protected] EDITORIAL STAFF Helena Halmari, Editor-in-Chief, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hanna Snellman, Co-Editor, University of Helsinki [email protected] Scott Kaukonen, Assoc. Editor, Sam Houston State University [email protected] Hilary-Joy Virtanen, Asst. Editor, Finlandia University [email protected] Sheila Embleton, Book Review Editor, York University [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Börje Vähämäki, Founding Editor, JoFS, Professor Emeritus, University of Toronto Raimo Anttila, Professor Emeritus, University of California, Los Angeles Michael Branch, Professor Emeritus, University of London Thomas DuBois, Professor, University of Wisconsin, Madison Sheila Embleton, Distinguished Research Professor, York University Aili Flint, Emerita Senior Lecturer, Associate Research Scholar, Columbia University Tim Frandy, Assistant Professor, Western Kentucky University Daniel Grimley, Professor, Oxford University Titus Hjelm, Associate Professor, University of Helsinki Daniel Karvonen, Senior Lecturer, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis Johanna Laakso, Professor, University of Vienna Jason Lavery, Professor, Oklahoma State University James P. Leary, Professor Emeritus, University of Wisconsin, Madison Andrew Nestingen, Associate Professor, University of Washington, Seattle Jyrki Nummi, Professor, University of Helsinki Jussi Nuorteva, Director General, The National Archives of Finland Juha Pentikäinen, Professor, University of Lapland Oiva Saarinen, Professor Emeritus, Laurentian University, Sudbury Beth L. -

And Estonian Kalev

Scandinavian Kalf and Estonian Kalev HILDEGARD MUST OLD ICELANDIC SAGAStell us about several prominent :men who bore the name Kalfr, Kalfr, etc.1 The Old Swedish form was written as Kalf or Kalv2 and was a fairly common name in Viking-age Scandinavia. An older form of the same name is probably kaulfR which is found on a runic stone (the Skarby stone). On the basis of this form it is believed that the name developed from an earlier *Kaoulfr which goes back to Proto-Norse *KapwulfaR. It is then a compound as are most of old Scandinavian anthroponyms. The second ele- ment of it is the native word for "wolf," ON"ulfr, OSw. ulv (cf. OE, OS wulf, OHG wolf, Goth. wulfs, from PGmc. *wulfaz). The first component, however, is most likely a name element borrowed from Celtic, cf. Old Irish cath "battle, fight." It is contained in the Old Irish name Cathal which occurred in Iceland also, viz. as Kaoall. The native Germ.anic equivalents of OIr. cath, which go back to PGmc. hapu-, also occurred in personal names (e.g., as a mono- thematic Old Norse divine name Hr;or), and the runic HapuwulfR, ON Hr;lfr and Halfr, OE Heaouwulf, OHG Haduwolf, Hadulf are exact Germanic correspondences of the hybrid Kalfr, Kalfr < *Kaoulfr. However, counterparts of the compound containing the Old Irish stem existed also in other Germanic languages: Oeadwulf in Old English, and Kathwulf in Old High German. 3 1 For the variants see E. H. Lind, Nor8k-i8liind8ka dopnamn och fingerade namn fran medeltiden (Uppsala and Leipzig, 1905-15), e. -

The Transformation of an Oral Poem in Elias Lönnrot's Kalevala

Oral Tradition, 8/2 (1993): 247-288 From Maria to Marjatta: The Transformation of an Oral Poem in Elias Lönnrot’s Kalevala1 Thomas DuBois The question of Elias Lönnrot’s role in shaping the texts that became his Kalevala has stirred such frequent and vehement debate in international folkloristic circles that even persons with only a passing interest in the subject of Finnish folklore have been drawn to the question. Perhaps the notion of academic fraud in particular intrigues those of us engaged in the profession of scholarship.2 And although anyone who studies Lönnrot’s life and endeavors will discover a man of utmost integrity, it remains difficult to reconcile the extensiveness of Lönnrot’s textual emendations with his stated desire to recover and present the ancient epic traditions of the Finnish people. In part, the enormity of Lönnrot’s project contributes to the failure of scholars writing for an international audience to pursue any analysis beyond broad generalizations about the author’s methods of compilation, 1 Research for this study was funded in part by a grant from the Graduate School Research Fund of the University of Washington, Seattle. 2 Comparetti (1898) made it clear in this early study of Finnish folk poetry that the Kalevala bore only partial resemblance to its source poems, a fact that had become widely acknowledged within Finnish folkoristic circles by that time. The nationalist interests of Lönnrot were examined by a number of international scholars during the following century, although Lönnrot’s fairly conservative views on Finnish nationalism became equated at times with the more strident tone of the turn of the century, when the Kalevala was made an inspiration and catalyst for political change (Mead 1962; Wilson 1976; Cocchiara 1981:268-70; Turunen 1982). -

Finnish Literature Society

Folklore Fellows’ NETWORK No. 1 | 2018 www.folklorefellows.fi • www.folklorefellows.fi • www.folklorefellows.fi Folklore Fellows’ NETWORK No. 1 | 2018 FF Network is a newsletter, published twice a year, related to Contents FF Communications. It provides information on new FFC volumes and on articles related to cultural studies by internationally recognised authors. The Two Faces of Nationalism 3 Pekka Hakamies Publisher Fin nish Academy of Science An Update to the Folklore Fellows’ Network and Letters, Helsinki Bulletin 4 Petja Kauppi Editor Pekka Hakamies [email protected] National Identity and Folklore: the Case of Ireland 5 Mícheál Briody Editorial secretary Petja Kauppi [email protected] Folk and Nation in Estonian Folkloristics 15 Liina Saarlo Linguistic editor Clive Tolley Finnish Literature Society (SKS) Archives 26 Editorial office Risto Blomster, Outi Hupaniittu, Marja-Leena Jalava, Katri Kalevala Institute, University of Turku Kivilaakso, Juha Nirkko, Maiju Putkonen & Jukka Saarinen Address Kalevala Institute, University of Turku Latest FFC Publications 31 20014 Turku, Finland FFC 313: Latvian Folkloristics in the Interwar Period. Ed. Dace Bula. FFC 314: Matthias Egeler, Atlantic Outlooks on Being at Home. Folklore Fellows on the internet www.folklorefellows.fi ISSN-L 0789-0249 ISSN 0789-0249 (Print) ISSN 1798-3029 (Online) Subscriptions Cover: Student of Estonian philology, Anita Riis (1927−1995) is standing at the supposed-to-be www.folklorefellows.fi Kalevipoeg’s boulder in Porkuni, northern Estonia in 1951. (Photo by Ülo Tedre. EKM KKI, Foto 1045) Editorial The Two Faces of Nationalism Pekka Hakamies his year many European nations celebrate their centenaries; this is not mere chance. The First World War destroyed, on top of everything else, many old regimes where peoples that had T lived as minorities had for some time been striving for the right to national self-determina- tion. -

Cr2016-Program.Pdf

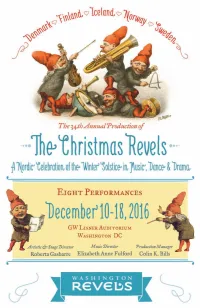

l Artistic Director’s Note l Welcome to one of our warmest and most popular Christmas Revels, celebrating traditional material from the five Nordic countries: Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden. We cannot wait to introduce you to our little secretive tomtenisse; to the rollicking and intri- cate traditional dances, the exquisitely mesmerizing hardingfele, nyckelharpa, and kantele; to Ilmatar, heaven’s daughter; to wild Louhi, staunch old Väinämöinen, and dashing Ilmarinen. This “journey to the Northlands” beautifully expresses the beating heart of a folk community gathering to share its music, story, dance, and tradition in the deep midwinter darkness. It is interesting that a Christmas Revels can feel both familiar and entirely fresh. Washing- ton Revels has created the Nordic-themed show twice before. The 1996 version was the first show I had the pleasure to direct. It was truly a “folk” show, featuring a community of people from the Northlands meeting together in an annual celebration. In 2005, using much of the same script and material, we married the epic elements of the story with the beauty and mystery of the natural world. The stealing of the sun and moon by witch queen Louhi became a rich metaphor for the waning of the year and our hope for the return of warmth and light. To create this newest telling of our Nordic story, especially in this season when we deeply need the circle of community to bolster us in the darkness, we come back to the town square at a crossroads where families meet at the holiday to sing the old songs, tell the old stories, and step the circling dances to the intricate stringed fiddles. -

The Role of the Kalevala in Finnish Culture and Politics URPO VENTO Finnish Literature Society, Finland

Nordic Journal of African Studies 1(2): 82–93 (1992) The Role of the Kalevala in Finnish Culture and Politics URPO VENTO Finnish Literature Society, Finland The question has frequently been asked: would Finland exist as a nation state without Lönnrot's Kalevala? There is no need to answer this, but perhaps we may assume that sooner or later someone would have written the books which would have formed the necessary building material for the national identity of the Finns. During the mid 1980s, when the 150th anniversary of the Kalevala was being celebrated in Finland, several international seminars were held and thousands of pages of research and articles were published. At that time some studies appeared in which the birth of the nation state was examined from a pan-European perspective. SMALL NATION STATES "The nation state - an independent political unit whose people share a common language and believe they have a common cultural heritage - is essentially a nineteenth-century invention, based on eighteenth-century philosophy, and which became a reality for the most part in either the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. The circumstances in which this process took place were for the most part marked by the decline of great empires whose centralised sources of power and antiquated methods of administrations prevented an effective response to economic and social change, and better education, with all the aspirations for freedom of thought and political action that accompany such changes." Thus said Professor Michael Branch (University of London) at a conference on the literatures of the Uralic peoples held in Finland in the summer of 1991. -

Hist Lab Esitelmä Ljubljana 10

Sari Saresto, Helsinki City Museum A presentation in Ljubljana, AN hist lab, 10th March 2006 Pohjola Insurance Building (1899-1901) International concepts are conveyed as a synthesis of national motifs and genuine materials In search of national identity: Finland was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1809. Russia wished to sever Finland’s close ties with former mother country Sweden and thus designated Helsinki as the capital of the Grand Duchy. Under Swedish rule, Turku had been the seat of government and higher education. Helsinki was geographically closer to Russia than the west coast city of Turku, (which almost seemed to gravitate towards Sweden), and thus also more easily supervised from St Petersburg. The Grand Duchy was allowed to retain its laws dating back to the time of Swedish rule. The language of government was Swedish, which was only spoken by 5% of the nation’s population. In Helsinki, however, nearly the entire population was Swedish-speaking. Nor was Swedish the language only of the upper echelons of society; it was spoken even by menial labourers. It wasn’t until the 1860s and the 1870s that the proportion of Finnish-speakers began to rapidly climb in Helsinki. The exhortation of “Swedes we are no longer, Russians we can never become, so let us be Finns” was first heard back in the 1820s. Finnish was the language of the people and its status was only highlighted by the Kalevala, the national epic compiled by Elias Lönnrot and published for the first time in 1835. This epic poem told, in Finnish, the tale of the world from its creation, speaking of an ancient, mystical past replete with legendary heroes, tribal wars, witches and magical devices. -

Politics, Migration and Minorities in Independent and Soviet Estonia, 1918-1998

Universität Osnabrück Fachbereich Kultur- und Geowissenschaften Fach Geschichte Politics, Migration and Minorities in Independent and Soviet Estonia, 1918-1998 Dissertation im Fach Geschichte zur Erlangung des Grades Dr. phil. vorgelegt von Andreas Demuth Graduiertenkolleg Migration im modernen Europa Institut für Migrationsforschung und Interkulturelle Studien (IMIS) Neuer Graben 19-21 49069 Osnabrück Betreuer: Prof. Dr. Klaus J. Bade, Osnabrück Prof. Dr. Gerhard Simon, Köln Juli 2000 ANDREAS DEMUTH ii POLITICS, MIGRATION AND MINORITIES IN ESTONIA, 1918-1998 iii Table of Contents Preface...............................................................................................................................................................vi Abbreviations...................................................................................................................................................vii ABBREVIATIONS ............................................................................................ VII 1 INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................3 1.1 CONCEPTUAL AND METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES ...............................................4 1.1.1 Conceptualising Migration ..................................................................5 1.1.1.1 Socio-Historical Migration Research....................................................................................5 1.1.1.2 A Model of Migration..........................................................................................................6 -

Signs of Giants in the Islands

Signs of Giants in the Islands Mare Kõiva and Andres Kuperjanov Estonian Literary Museum, Department of Folkloristica, Estonia Supported by ESF grant 8147 Signs of Giants in the Islands Mare Kõiva and Andres Kuperjanov Estonian Literary Museum, Department of Folkloristica, Estonia Background. The island of Gozo features a wonderful monument – a temple from 3500 BC with walls 3 meters high. According to folklore, the Gghantia temple was built by giants. The present paper gives an overview of giant lore from Estonia (42,000 square km), by the Baltic Sea, bordered by Finland and Sweden in the north, Latvia in the south and Russia in the east. Estonia has about 1000 islands in the Baltic sea, most of the smaller islands uninhabited or habited by a few families only. During the time under the Soviet Union, many of the beautiful islands were closed border region, occupied by army bases or used for bombing practice with local people turned out. The largest western islands are Saaremaa (Ösel), with Hiiumaa (literally Giantland) north of it and Muhumaa forming a triangle, as well as the former coastal Estonian Swedes islands Kihnu, Ruhnu and Vormsi. Saaremaa has glorious ancient and recent history. All the bigger islands have remarkably unique features in their folk culture and lifestyles, with division of labour and social relations until recent times quite different from the mainland. Kihnu and Ruhnu are reservoirs of unique culture, Kihnu is on the UNESCO world heritage list for its folklore We are going to give an overview of one aspect of Saaremaa’s identity – its giant lore, found in folk narratives and contemporary tourism as well as the self- image of island dwellers.