VECTOR Nov-Dec 19"7B Frederik Pohl Interview the B.S.F.A. Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works of Speculative Fiction

Catalogue XV 116 Rare Works Of Speculative Fiction About Catalogue XV Welcome to our 15th catalogue. It seems to be turning into an annual thing, given it was a year since our last catalogue. Well, we have 116 works of speculative fiction. Some real rarities in here, and some books that we’ve had before. There’s no real theme, beyond speculative fiction, so expect a wide range from early taproot texts to modern science fiction. Enjoy. About Us We are sellers of rare books specialising in speculative fiction. Our company was established in 2010 and we are based in Yorkshire in the UK. We are members of ILAB, the A.B.A. and the P.B.F.A. To Order You can order via telephone at +44(0) 7557 652 609, online at www.hyraxia.com, email us or click the links. All orders are shipped for free worldwide. Tracking will be provided for the more expensive items. You can return the books within 30 days of receipt for whatever reason as long as they’re in the same condition as upon receipt. Payment is required in advance except where a previous relationship has been established. Colleagues – the usual arrangement applies. Please bear in mind that by the time you’ve read this some of the books may have sold. All images belong to Hyraxia Books. You can use them, just ask us and we’ll give you a hi-res copy. Please mention this catalogue when ordering. • Toft Cottage, 1 Beverley Road, Hutton Cranswick, UK • +44 (0) 7557 652 609 • • [email protected] • www.hyraxia.com • Aldiss, Brian - The Helliconia Trilogy [comprising] Spring, Summer and Winter [7966] London, Jonathan Cape, 1982-1985. -

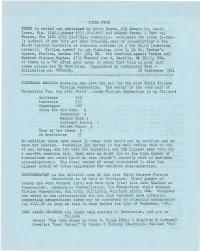

THYME FIVE THYME Is Edited and Published by Irwin Hirsh, 27/9 Domain Rd, South Yarra, Vic

THYME FIVE THYME is edited and published by Irwin Hirsh, 27/9 Domain Rd, South Yarra, Vic. 3141,(phones (03) 26-1966) and Andrew Brown, 5 York St, Prahan, Vic 318-1 (03) 51-7702), Australia. Available for trade (1-for- lj 2-for-l if you both get your fanzine), news or subscriptions 6 for -£2.00 (.within Australia or overseas surface) or 3 for tf2.00, (overseas airmail). British agents Joseph Nicholas, Boom 9, 94 St. George’s Square, Pimlico, London SW1Y 3QY, UK. Nth American agents Teresa and Patrick Nielsen Hayden, 4712 Fremont Ave N, Seattle, WA 98.IO3, USA. If there is a *X* after your name, i.t means that thia is your last' isaue unless-, you Do Something. Registered by Australian Post - publication no. VBH2625. 28 September 1981 AUSTRALIA LOOSES: Austalia has lost the bid for the 41st World Science Fiction Convention. The result of the vote held at Denvention Two, the 39th World lienee Fiction Convention is as follows: Baltimore . 916 Australia 523 Copenhagen 188 Write In: New York 5 Johnstown 4 Medlow Bath 1 Rottnest Isalnd 1 Palnet Sharo 1 None of the Above 3 No Rreference 37 In addition there were about 30 votes that could not be verified and so were not counted. Australia did better in the mail voting than in the at con voting, and the vote for Australia was the highest ever vote for a non-Nth American bid. Both were no doubt due to the high number of Australians who voted (most of whom wouldn’t normally vote in worldcon site-selection). -

Dragon Magazine

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chief: Kim Mohan Shorter and stronger Editorial staff: Marilyn Favaro Roger Raupp If this isnt one of the first places you Patrick L. Price turn to when a new issue comes out, you Mary Kirchoff may have already noticed that TSR, Inc. Roger Moore Vol. VIII, No. 2 August 1983 Business manager: Mary Parkinson has a new name shorter and more Office staff: Sharon Walton accurate, since TSR is more than a SPECIAL ATTRACTION Mary Cossman hobby-gaming company. The name Layout designer: Kristine L. Bartyzel change is the most immediately visible The DRAGON® magazine index . 45 Contributing editor: Ed Greenwood effect of several changes the company has Covering more than seven years National advertising representative: undergone lately. in the space of six pages Robert Dewey To the limit of this space, heres some 1409 Pebblecreek Glenview IL 60025 information about the changes, mostly Phone (312)998-6237 expressed in terms of how I think they OTHER FEATURES will affect the audience we reach. For a This issues contributing artists: specific answer to that, see the notice Clyde Caldwell Phil Foglio across the bottom of page 4: Ares maga- The ecology of the beholder . 6 Roger Raupp Mary Hanson- Jeff Easley Roberts zine and DRAGON® magazine are going The Nine Hells, Part II . 22 Dave Trampier Edward B. Wagner to stay out of each others turf from now From Malbolge through Nessus Larry Elmore on, giving the readers of each magazine more of what they read it for. Saved by the cavalry! . 56 DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is pub- I mention that change here as an lished monthly for a subscription price of $24 per example of what has happened, some- Army in BOOT HILL® game terms year by Dragon Publishing, a division of TSR, Inc. -

GOTHIC HORROR Gothic Horror a Reader's Guide from Poe to King and Beyond

GOTHIC HORROR Gothic Horror A Reader's Guide from Poe to King and Beyond Edited by Clive Bloom Editorial matter and selection © Clive Bloom 1998 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London WIP 9HE. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. __ First published 1998 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-0-333-68398-9 ISBN 978-1-349-26398-1 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-26398-1 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 00 99 98 __ Published in the United States of America 1998 by ST. MARTIN'S PRESS, INC., Scholarly and Reference Division, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. -

A Publication of the Science Fiction Research Association in This Issue

294 Fall 2010 Editors Karen Hellekson SFRA 16 Rolling Rdg. A publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Jay, ME 04239 Review [email protected] [email protected] Craig Jacobsen English Department Mesa Community College 1833 West Southern Ave. Mesa, AZ 85202 [email protected] In This Issue [email protected] SFRA Review Business Managing Editor Out With the Old, In With the New 2 Janice M. Bogstad SFRA Business McIntyre Library-CD University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Thanks and Congratulations 2 105 Garfield Ave. 101s and Features Now Available on Website 3 Eau Claire, WI 54702-5010 SFRA Election Results 4 [email protected] SFRA 2011: Poland 4 Nonfiction Editor Features Ed McKnight Feminist SF 101 4 113 Cannon Lane Research Trip to Georgia Tech’s SF Collection 8 Taylors, SC 29687 [email protected] Nonfiction Reviews The Business of $cience Fiction 9 Fiction Editor Selected Letters of Philip K. Dick 9 Edward Carmien Fiction Reviews 29 Sterling Rd. Directive 51 10 Princeton, NJ 08540 Omnitopia Dawn 11 [email protected] The Passage: A Novel 12 Media Editor Dust 14 Ritch Calvin Gateways 14 16A Erland Rd. The Stainless Steel Rat Returns 15 Stony Brook, NY 11790-1114 [email protected] Media Reviews The SFRA Review (ISSN 1068- I’m Here 16 395X) is published four times a year by Alice 17 the Science Fiction Research Association (SFRA), and distributed to SFRA members. Splice 18 Individual issues are not for sale; however, Star Trek: The Key Collection 19 all issues after 256 are published to SFRA’s Website (http://www.sfra.org/) no fewer than The Trial 20 10 weeks after paper publication. -

Hell's Cartographers : Some Personal Histories of Science Fiction Writers

Some Personal Histor , of Science Fiction Writers Robert Silverberg/Alfred Bester Harry Harrison/Damon Knight Frederick Pohl/Brian Aldiss BOSTON PUBLIC LIBRARY Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/hellscartographeOObest hell’s cartographers hell’s cartographers Some Personal Histories of Science Fiction Writers with contributions by Alfred Bester Damon Knight Frederik Pohl Robert Silverberg Harry Harrison Brian W. Aldiss Edited by Brian W. Aldiss Harry Harrison HARPER & ROW, PUBLISHERS New York, Hagerstown, San Francisco, London Note: The editors wish to state that the individual contributors to this volume are responsible only for their own opinions and statements. hell’s cartographers. Copyright ©1975 by SF Horizons Ltd. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information address Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc., 10 East 53rd Street, New York, N.Y. 10022. FIRST U.S. EDITION Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: Hell’s cartographers. Bibliography: p. 1. Authors, American — Biography. 2. Aldiss, Brian Wilson, 1925- — Biography. 3. Science fiction, American — History and criticism — Addresses, essays, lectures. 4. Science fiction— Authorship. I. Aldiss, Brian Wilson, 1925- II. Harrison, Harry. PS129.H4 1975 813 / .0876 [B] 75-25074 ISBN 0-06-010052-4 76 77 78 79 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Contents Introduction 1 Robert Silverberg: Sounding Brass, Tinkling Cymbal 7 Alfred Bester: My Affair With Science Fiction 46 Harry Harrison: The Beginning of the Affair 76 Damon Knight: Knight Piece 96 Frederik Pohl: Ragged Claws 144 Brian Aldiss: Magic and Bare Boards 173 Appendices: How We Work 211 Selected Bibliographies 239 A section of illustrations follows page 122 Introduction A few years ago, there was a man living down in Galveston or one of those ports on the Gulf of Mexico who helped make history. -

Science-Fiction Srudies

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been repmôuced from the micrdilm master. UMI films the text difecüy from the original or copy submitted. mus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewnter face, while ofhen may be from any type of cornputer printer. The quality of this repfoâuction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistind print, cdored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedttrrough, substandard margins, and imwr alignment can adversely aff&zt reprodudion. In the unlikely event tnat the author did not send UMI a cornplete manuscript and there are missing pages, these wïll be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e-g., maps, drawings, charb) are reproduced by sectiming the original, beginning at the upper bft-hand corner and cantinuing from left to right in eqwl seaiocis with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduoed xerographicaliy in mis copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" bbck and mite photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI direcüy to order. Be11 8 Howell Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 481064346 USA 800-521-0800 NOTE TO USERS The original manuscript received by UMI contains pages with indistinct andlor slanted print. Pages were microfilmed as received. # This reproduction is the best copy available The Cyborg. Cyberspace. and Nonh herican Science Fiction Salvatore Proietti Department of English iht~GiI1University. Monneal July 1998 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Q Salvatore Proietti, 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. -

Download Now Free Download Here Download Ebook

kC72h (Mobile ebook) Wolfbane Online [kC72h.ebook] Wolfbane Pdf Free Frederik Pohl, C.M. Kornbluth audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #2465575 in eBooks 2017-02-08 2017-02-08File Name: B01N2B6I3P | File size: 58.Mb Frederik Pohl, C.M. Kornbluth : Wolfbane before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Wolfbane: 5 of 5 people found the following review helpful. Another Pohl-Kornbluth WinnerBy ElliotFrederik Pohl and C.M. Kornbluth are probably best known for two of their collaborations, "The Space Merchants" and "Gladiator-at-Law," two scathing satires of 1950s American capitalism which were not only funny send-ups of advertising (Merchants) and the legal profession (Gladiator) but also fast-paced adventures set in a future (but all-too-recognizable) America. "Wolfbane" is not nearly as well known, but is at least as good as those two classics, albeit very different in tone. The social satire is not nearly as pronounced in "Wolfbane," a story of a future earth that has been literally stolen from its orbit by unseen aliens. The sociological element is still there-- the book begins by imagining the type of society that would grown up in a world full of privation, in which humans are helpless victims of aliens who are unseen and inscrutable-- but the caustic criticism of 1950s America is replaced by an almost elegiac tone. As the book goes on, the tone changes, as one man slowly learns that it is possible to rebel against the aliens. -

Scientifiction 37

Scientifiction New Series #37 Scientifiction A publication of FIRST FANDOM, the Dinosaurs of Science Fiction New Series #37 , 3rd quarter 2013 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Greetings, everyone! First Fandom website. The new look From the reports I received on the will feature photographs, articles, Worldcon, everyone seemed to have interviews and a history of our a great weekend, spending time with awards. Please send your ideas and friends, enjoying programming and any contributions directly to me. hearing the announcement of First Change of Address for the Cokers Fandom’s Awards. David A. Kyle My wife Linda and I are nearly spent a lot of time greeting fans at finished moving into our new home! the First Fandom exhibit table. Please reach us 4813 Lighthouse Next year, the Worldcon will be held Road, Orlando, FL 32808. Our new in London. They will be celebrating telephone number is (407) 532-7555. three quarters of a century since the New Contact Information first Worldcon was held in 1939. Mike Glyer Remembering 1507-1/2 South Sixth Avenue During the past several months, Arcadia, CA 91006 Richard Matheson and Frederik Pohl Tel: (626) 305-1004 both passed away. These dear men [email protected] were giants in our field, and they will We Need Your E-Mail Address be missed. Please see their obituary notices on pages 8-10 in this issue. We are asking all members who are still receiving paper copies of the FAPA newsletter to please provide me with I prepared a long contribution for the an e-mail address, so that they can latest mailing of the Fantasy enjoy the expanded, full-color Amateur Press Association. -

Home Truths: Women Writing Science in the Nuclear Dawn

Home truths: women writing Keywords domestic Cold War science in the nuclear dawn history 1 natural science Diana Newell feminist literature science-fiction Abstract literature This paper develops a political reading of women writers’/writer-editors’ Rachel Carson involvement in the American atomic age, Cold War-era fields of science fiction atomic age and popular science writing. Judith Merril (1928-97) in her post-war 1 My thanks to Linda science-fiction writing and Rachel Carson (1907-64) in her international Lear, Leslie Paris, best-selling anti-pesticide polemic, Silent Spring (1962), capitalized on Arthur Ray, Jim Rupert, and Allan popular, mass-market literary genres as vehicles for social criticism in what Weiss for thoughtful Jessica Wang calls an ‘Age of Anxiety’ in which open criticism of American comments on this research. Versions of science, government, and the industrial-military complex carried high personal this paper were deliv- risk. Importantly, both explicitly politicized images of domesticity, thus ered at the 10th Biannual Swiss joining women’s history to some of the most sweeping changes of the twenti- Congress on eth century. Women’s History, ‘Gender and Knowledge’, The US atomic bombing of Hiroshima in 1945 engendered in members University of of the Anglo-American science fiction communities a certain glow of Misericorde, Fribourg, Switzerland, 18-19 self-congratulation for having brilliantly predicted a world-changing sci- February 2000; and entific development.2 The general mixed sense of elation among writers the International Conference on the and fans of science fiction is captured in British writer Brian Aldiss’s per- Nature of Gender and sonal reflection in the 1970s: ‘Whatever else the A-bomb meant to .. -

World Fantasy Convention 2006

The 32nd Annual World Fantasy Convention 2006 MInd of My Mind (c) John Jude Palencar November 2 - 5, 2006 The Renaissance Hotel Austin, Texas Progress Report #4 Address Service Requested Service Address http://www.fact.org/wfc2006 Austin Texas, 78755 Texas, Austin P.O. Box 27277 27277 Box P.O. WFC 2006 WFC Hotel WFC 2006 will take place at the Renaissance Hotel, which is located in a part of Austin called The Arboretum. The Arboretum is located about 7 miles from downtown Austin in a fully-developed shopping and retail area. Sitting on Hwy 183 between Capital of Texas Highway and Great Hills Trail, the Arboreteum nestles into the hills of NW Austin. It is a green place, with scenic walks and quiet places to sit and read or chat, but has the advantage of the proximity Guests of Honor of quality retail shopping. The Arboretum has something for everyone. The Renaissance Hotel 9721 Arboretum Boulevard Austin, Texas 78759 Glen Cook 1-512-343-2626 or 1-800-HOTELS-1 http://www.marriott.com/property/propertypage/AUSSH Dave Duncan Group Codes Single-double: facfaca Triple-Quad: facacb Room rate for Single - Double beds: $135. Robin Hobb Art Show The art show is currently soliciting admissions for juried art until May 31, 2006. Please see the Toastmaster website for more information. Bradley Denton Dealer’s Room The Dealer’s room is juried. Please contact Greg Ketter at [email protected] for more Editor Guest of Honor information. Glenn Lord Robert E. Howard Excursion For attendees who want to see a little more of Robert E. -

The Fannish E-Zine of the West Coast Science Fiction Association Dedicated to Promoting the West Coast Science Fiction Community #2 Oct 2007

WCSFAzine The Fannish E-zine of the West Coast Science Fiction Association Dedicated to Promoting the West Coast Science Fiction Community #2 Oct 2007 1 IMPORTANT STUFF YOU CAN SAFELY IGNORE WCSFAzine Issue # 2, Oct 2007, Volume 1, Number 2, Whole number 2, is the monthly E-zine of the West Coast Science Fiction Association ( founded 1993 ), a registered society with the general mandate of promoting Science Fiction and the specific focus of sponsoring the annual VCON Science Fiction Convention ( founded 1971 ). Anyone who attends VCON is automatically a member of WCSFA, as is anyone who belongs to the British Columbia Science Fiction Association, a social organization ( founded 1970 ) which is the proud owner of the VCON trademark. Said memberships involve voting privileges at WCSFA meetings. Current Executive of WCSFA: President: Palle Hoffstein. Vice-President/VCON Hotel Liaison: Keith Lim. Treasurer: Tatina Osokin. Secretary, & Archivist: R. Graeme Cameron. Member-At-Large: Danielle Stephens (VCON 32 Chair ). Member-At-Large: Deej Barens. Member-At-Large: Christina Carr. Since WCSFAzine is NOT the official organ of WCSFA, the act of reading WCSFAzine does not constitute membership in WCSFA or grant voting privileges in WCSFA. Therefore you don’t have to worry about WCSFA policies, debates, finances, decisions, etc. Unless you want to. Active volunteers always welcome. WCSFA Website: < http://www.user.dccnet.com/clintbudd/WCSFA/ > IMPORTANT STUFF THAT IS VERY COOL Your membership fee: Nothing! Send your subscription fee to: Nobody! Your responsibilities: None! Your obligations: None! Membership requirements: None! Got something better to do: No problem! WCSFAzine IS a fannish E-zine publication sponsored by WCSFA to promote and celebrate every and all aspects of the Science Fiction Community on the West Coast of Canada.