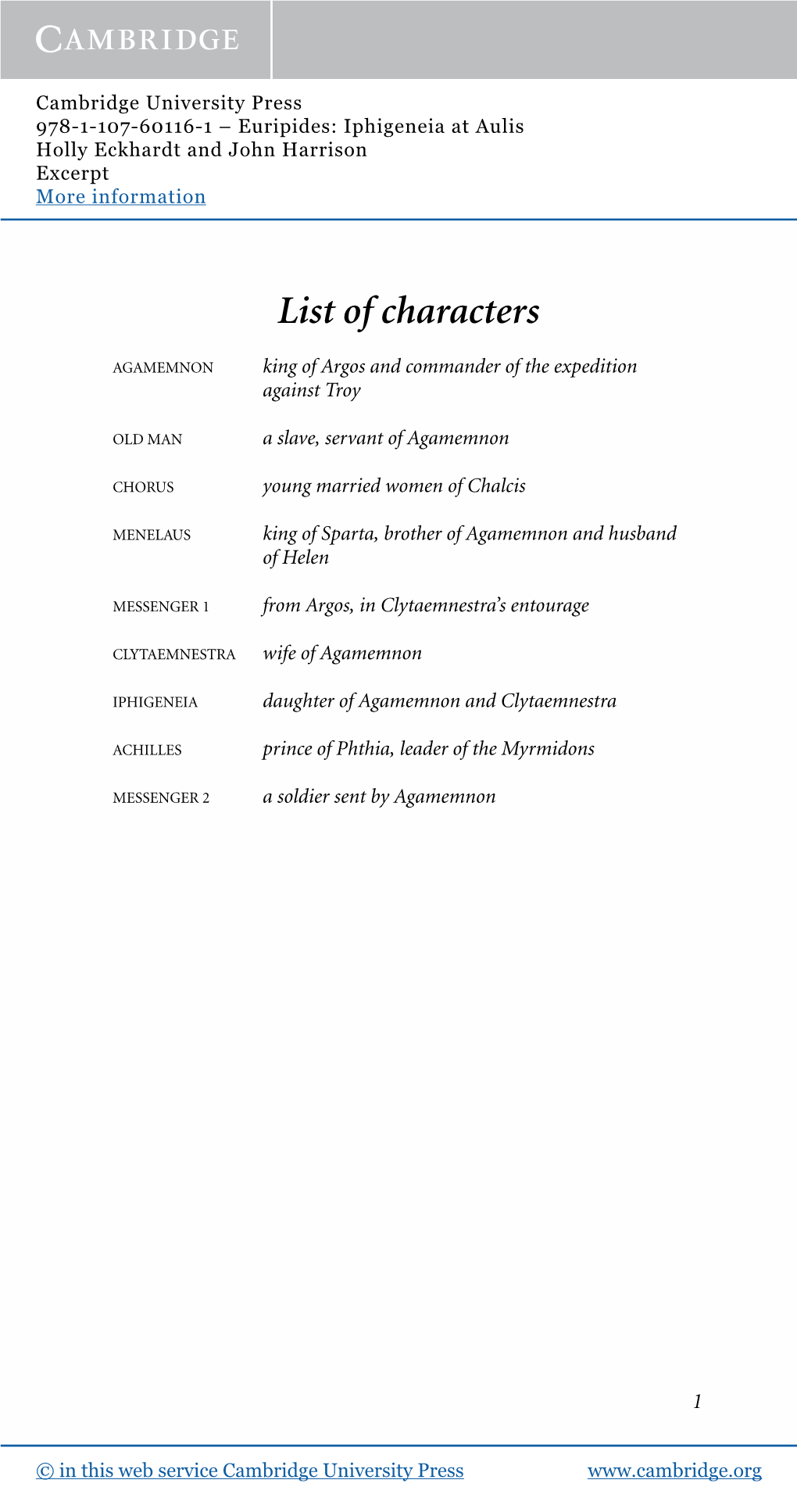

List of Characters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae

historia 68, 2019/4, 413–435 DOI 10.25162/historia-2019-0022 Jeffrey Rop The Phocian Betrayal at Thermopylae Abstract: This article makes three arguments regarding the Battle of Thermopylae. First, that the discovery of the Anopaea path was not dependent upon Ephialtes, but that the Persians were aware of it at their arrival and planned their attacks at Thermopylae, Artemisium, and against the Phocians accordingly. Second, that Herodotus’ claims that the failure of the Pho- cians was due to surprise, confusion, and incompetence are not convincing. And third, that the best explanation for the Phocian behavior is that they were from Delphi and betrayed their allies as part of a bid to restore local control over the sanctuary. Keywords: Thermopylae – Artemisium – Delphi – Phocis – Medism – Anopaea The courageous sacrifice of Leonidas and the Spartans is perhaps the central theme of Herodotus’ narrative and of many popular retellings of the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE. Even as modern historians are appropriately more critical of this heroizing impulse, they have tended to focus their attention on issues that might explain why Leo- nidas and his men fought to the death. These include discussion of the broader strategic and tactical importance of Thermopylae, the inter-relationship and chronology of the Greek defense of the pass and the naval campaign at Artemisium, the actual number of Greeks who served under Leonidas and whether it was sufficient to hold the position, and so on. While this article inevitably touches upon some of these same topics, its main purpose is to reconsider the decisive yet often overlooked moment of the battle: the failure of the 1,000 Phocians on the Anopaea path. -

Greek Myths and Legends Pdf Free Download

GREEK MYTHS AND LEGENDS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Cheryl Evans | 64 pages | 08 Jan 2008 | Usborne Publishing Ltd | 9780746087190 | English | London, United Kingdom Greek Myths and Legends PDF Book It is thought that she took the Golden Age of Man with her when she left for the heavens in disgust. Eventually, he fell in love with and married Eurydice, but on their wedding day, she was bitten by a snake and died. His wandering lasted for no less than ten years! Next, it was the turn of goddess Athena. Also the trojan war they missed a part. They are naturally drawn to the land. As soon as the bull reached the beach, it ran into the water. While most ancient cultures were taught to fear their gods, the Greeks tried to make their gods relatable by giving them human-like qualities. Leto in ancient myths of Greece was the representation of motherhood. Out of pity, Athena transformed her into a spider, so she could continue weaving without having to break her oath. This tragic story has inspired many painters and it is the basic concept for many operas and songs. Once he came of age he tried to reclaim the throne. Oedipus, upon realizing what he had done and seeing Jocasta's dead body, stabbed his eyes out and was exiled. They are very similar, and Aphrodite and Eros escape from Typhon safely due to the help of two fish. It was Hercules first trial where he was given the task of finding and then killing the Nemean Lion. They have a lot in common. -

Mixing Characteristics Under Tide, Meteorological and Oceanographic Conditions in the Euboean Gulf Greece

Computational Water, Energy, and Environmental Engineering, 2019, 8, 99-123 https://www.scirp.org/journal/cweee ISSN Online: 2168-1570 ISSN Print: 2168-1562 Mixing Characteristics under Tide, Meteorological and Oceanographic Conditions in the Euboean Gulf Greece Evangelos Tsirogiannis, Panagiotis Angelidis, Nikolaos Kotsovinos Division of Hydraulics, Department of Civil Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace, Kimmeria Campus, Xanthi, Greece How to cite this paper: Tsirogiannis, E., Abstract Angelidis, P. and Kotsovinos, N. (2019) Mixing Characteristics under Tide, Meteo- The mixing characteristics in the marine environment of the Euboean Gulf rological and Oceanographic Conditions in are studied. The Estuarine and Lake CΟmputer Model three-dimensional the Euboean Gulf Greece. Computational hydrodynamic model has been used, to simulate numerically the effects of the Water, Energy, and Environmental Engi- neering, 8, 99-123. strong tide conditions, the atmospheric forcing, and the oceanographic con- https://doi.org/10.4236/cweee.2019.84007 ditions. Water age was calculated in all computational cells and its renewal was examined with the “pure” water of the open sea both on the surface Received: September 27, 2019 Accepted: October 20, 2019 layers, where the effect of tide and wind was pronounced, as well as on the Published: October 23, 2019 deeper layers and bottom. It was investigated if in surface layers the tide and the wind restore the water of the study area, thus preventing its renewal. In Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and the remote area, the mixing and dilution of the pollutants contained in the Scientific Research Publishing Inc. This work is licensed under the Creative treated municipal waste of five installed diffusers in this complex hydrody- Commons Attribution International namic field, generated by the aforementioned loads, is simulated. -

Archimedes in Cephalonia and in Euripus Strait: Modern Horizontal Archimedean Screw Turbines for Recovering Marine Power

JOURNAL OF Engineering Science and Journal of Engineering Science and Technology Review 6 (1) (2013) 44 -51 estr Technology Review J Research Article www.jestr.org Archimedes in Cephalonia and in Euripus Strait: Modern Horizontal Archimedean Screw Turbines for Recovering Marine Power A. Stergiopoulou1 and V. Stergiopoulos2,* 1Department of Water Resources and Environment Engineering, School of Civil Engineering, National Technical University of Athens, Athens 15780, Greece. 2. Higher School of Pedagogical and Technological Education, Division of Hydropower, ASPETE Campus, Athens 14121, Greece. Received 3 March 2013; Accepted 3 May 2013 ___________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract The possibility of exploiting sea and tidal currents for power generation has given little attention in Mediterranean countries despite the fact that these currents representing a large renewable energy resource could be exploited by “modern old technologies” to provide important levels of electric power. It is also well known that one of the oldest machines still in use is the Archimedes screw, a device for lifting water for irrigation and drainage, invention credited to Archimedes. The main aim of this paper is to present a new small hydro philosophy of recovering the unexploited coastal and tidal hydraulic potential by following an efficient “Archimedean philosophy” and by using modern horizontal-axis unconventional cochlear turbines. Our work proposes “the presence of Archimedes in Cephalonia and in Euripus Strait” and the optimal “Archimedean” exploitation of the Euripus tidal current and of the Cephalonia coastal paradox cross flowing continuously from Livadi Gulf to the Gulf of Sami. The present paper intends to prove the useful modern rediscovering of some old Archimedean ideas concerning spiral water wheel technologies under the form of new and efficient horizontal-axis Archimedean hydropower turbines. -

Pushing the Boundaries of Myth: Transformations of Ancient Border

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PUSHING THE BOUNDARIES OF MYTH: TRANSFORMATIONS OF ANCIENT BORDER WARS IN ARCHAIC AND CLASSICAL GREECE A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF CLASSICS: ANCIENT MEDITERRANEAN WORLD BY NATASHA BERSHADSKY CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MARCH 2013 UMI Number: 3557392 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3557392 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 Acknowledgements I would like to express my deep gratitude to the members of my dissertation committee, Jonathan Hall, Christopher Faraone, Gloria Ferrari Pinney and Laura Slatkin, whose ideas and advice guided me throughout this research. Jonathan Hall’s energy and support were crucial in spurring the project toward completion. My identity as a classicist was formed under the influence of Gregory Nagy. I would like to thank him for the inspiration and encouragement he has given me throughout the years. Daniela Helbig’s assistance was invaluable at the finishing stage of the dissertation. I also thank my dear colleague-friends Anna Bonifazi, David Elmer, Valeria Segueenkova, Olga Levaniouk and Alexander Nikolaev for illuminating discussions, and Mira Bernstein, Jonah Friedman and Rita Lenane for their help. -

The Euripus Bridges - Evia, Halkida

The Euripus Bridges - Evia, Halkida The region of central Evia is characterized by the brilliant historical presence of two of the most important cities of ancient Greece. Chalkida and Eretria, long before the appearance of Athens, have established the world-wide mark of the Greek culture. Chalkida [ the city where Nikos Skalkottas was born] has always been the natural entrance to Evia. The capital of Evia, astonishingly beautiful indeed, instantly wins over anyone who crosses the old bridge of Euripus and Evia. A city, with a history and culture which is lost in the depths of the ages. By the many colonies of Chalkida, (Chalkidiki. S. Italy, Ionian coastland etc), civilization was passed to the world through written speech. The well- known Chalkidiko or Kimaiko alphabet (ancestor of the Latin alphabet) was the first attempt of man to immortalize his experiences and history. The Euripus Strait, is a narrow channel of water separating the Greek island of Euboea in the Aegean Sea from Boeotia in mainland Greece. The strait's principal port is Chalcis on Euboea, located at the strait's narrowest point. The strait is subject to strong tidal currents which reverse direction approximately four times a day. Tidal flows are very weak in the Eastern Mediterranean, and the strait is a remarkable exception. Water flow peaks at about 12 km/hour, either northwards or southwards, and lesser vessels are often incapable of sailing against it. When nearing flow reversal, sailing is even more precarious because of vortex formation. The first bridge across Euripus was built by the Emperor Justinian I in 540 AD. -

Antiquity, Primitivism and National Stereotypes in Greek Travel Writing

ANTIQUITY, PRIMITIVISM AND NATIONAL STEREOTYPES IN GREEK TRAVEL WRITING (1850-1870) by GEORGIA DRAKOU A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies School of History and Cultures The University of Birmingham January 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to study the representations of rural people in Greek travel writing over the period 1850-1870, by focusing on the way in which such representations reveal the process of national identity formation. In the first chapter, I address the issue of travellers’ lack of interest in the peasant way of life, and I undertake to explore the significance of this ‘absence’. In the second chapter, I examine travel texts pursuing to establish a direct connection of rural customs and mores with the ancient Greek ones. In the third chapter, I analyse the way in which the ethnographical concern of travel writing brings to the fore primitive aspects of rural life. The concept of primitiveness will be further developed in the last two chapters, in the context of race and gender representations in the observation of Greek peasants. -

From Tyranny to Democracy Prescribed Source Booklet

Qualification Accredited GCSE (9–1) Prescribed Source Booklet ANCIENT HISTORY J198 For first teaching in 2017 From Tyranny to Democracy, 546–483 BC Version 2 www.ocr.org.uk/gcseancienthistory Prescribed Sources Booklet Overview of the depth study The Emergence Cleisthenes and his rivalry with Isagoras, including the of Democracy in involvement of Sparta; the introduction of isegoria by The origin of political systems has fascinated writers and thinkers in every age, Athens Cleisthenes; Cleisthenes’ reforms, including restructuring Map and ancient Greek political history is a particularly interesting and varied area of of tribes, demes and phratries, and the reorganisation of exploration for students of the ancient world. The events covered in this depth the boule; Spartan attempt to restore Hippias; Corinthian study are some of the most interesting and fascinating in Greek history. The first arguments against restoring Hippias as tyrant in Athens; area of the specification alone allows students to read about a faked murder Corinthian opposition to tyranny on principle – the attempt, the impersonation of a goddess, a sexless marriage, a spurned lover, examples of Cypselus and Periander. Introduction an insulted aristocratic girl, assassination and torture. This depth study allows Democracy in Athenian democratic policy toward Persia; establishment students to understand the nature of two different political systems: tyranny action of the ten strategoi; Athenian decision to support and democracy through the actions and colourful personalities -

Ancient Greece from the Air" Slides 931 Slides

RAYMOND V. SCHODER, S.J. (1916-1987) Classical Studies Department "Ancient Greece from the Air" Slides 931 slides Ace. No. 89-15 Computer Name: SCHODER.GRE 7 Meta I Slide Boxes Location: I8C In August 1962, August 1967, and June of 1968 Fr. Raymond V. Schader, S.J., photographed ancient Greek archeological sites from the air. Most of these photographs were taken through the open door of a DC3 plane piloted by and belonging to the Hellenic Air Force. Of these photographs 140 were published in Wings over Hcllas: Ancient Greece from the Air by Raymond V. Schader, S.J. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1974). 1 In the introduction to his work Fr. Schader explains the procedures employed in taking these photographs and the aim which motivated him: to present all important excavated sites of ancient Greece, both mainland and islands and from Minoan to Roman times, from this advantageous point of view as a new aid to archeology and to historical studies as well as to visitors to the sites .... Only ancient sites are included, though many medieval centres are also meaningful from the air and I have photographed them also. The photographic slides taken by Fr. Schoder during this project make up the bulk of the collection of slides listed below. Although ancient ruins arc the predominant subject of the slides, there are several slides depicting contemporary cities from above. Interesting to note arc the first three slides showing the technique which Fr. Schader used to photograph from the air. The slides arc maintained numerically in the order in which they were transferred to the Archives. -

Replace This with the Actual Title Using All Caps

THRACE AND THE ATHENIAN ELITE, CA. 550-338 BCE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Matthew Alan Sears May 2011 © 2011 Matthew Alan Sears THRACE AND THE ATHENIAN ELITE, CA. 550-338 BCE Matthew Alan Sears, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 This dissertation examines the personal ties between elite Athenians and Thrace from the mid sixth century to the mid fourth century BCE in four case studies – the Philaids and the Thracian Chersonese, Dieitrephes and the massacre at Mycalessus, the northern campaigns of Alcibiades and Thrasybulus, and the fourth century mercenary general Iphicrates. In order to highlight further the particular qualities of those elites who were drawn to Thrace, the final chapter examines figures that shared several traits with Athenian Thracophiles but did not make extensive use of Thracian ties. The relationship between Athens and Thrace is explored in terms of three broad categories – political, military, and cultural. Given that there continued to be ambitious elites in Athens even after Solon‟s reforms and the subsequent climate of increasing political equality between male citizens, Thrace served as a political safety valve. Thrace was a place to which elites could remove themselves should they be unwilling or unable to engage in the prevailing ideological system and should mechanisms like ostracism fail to achieve the desired result, such as the removal of their more powerful competition. Experience with Thracians was often the catalyst for military innovation. Several Athenians were pioneers in adopting Thracian methods of warfare. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Disease and Difference in Three Platonic Dialogues: Gorgias, Phaedo, and Timaeus Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90s0h7r8 Author Ricciardone, Chiara T. Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Disease and Difference in Three Platonic Dialogues: Gorgias, Phaedo, and Timaeus by Chiara Teresa Ricciardone A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor G.R.F. Ferrari, Co-chair Professor Ramona Naddaff, Co-chair Professor David Bates Professor Daniel Boyarin Professor Marianne Constable Professor Hans Sluga Summer 2017 Abstract Difference and Disease in Three Platonic Dialogues: Gorgias, Phaedo, and Timaeus by Chiara Teresa Ricciardone Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric with the designated emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professors G.R.F. Ferrari and Ramona Naddaff, Co-chairs This study traces a persistent connection between the image of disease and the concept of difference in Plato’s Gorgias, Phaedo, and Timaeus. Whether the disease occurs in the body, soul, city, or cosmos, it always signals an unassimilated difference that is critical to the argument. I argue that Plato represents—and induces—diseases of difference in order to produce philosophers, skilled in the art of differentiation. Because his dialogues intensify rather than cure difference, his philosophy is better characterized as a “higher pathology” than a form of therapy. An introductory section on Sophist lays out the main features of the concept of difference- in-itself and concisely presents its connection to disease. -

Disease and Difference in Three Platonic Dialogues: Gorgias, Phaedo, and Timaeus

Disease and Difference in Three Platonic Dialogues: Gorgias, Phaedo, and Timaeus by Chiara Teresa Ricciardone A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric and the Designated Emphasis in Critical Theory in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor G.R.F. Ferrari, Co-chair Professor Ramona Naddaff, Co-chair Professor David Bates Professor Daniel Boyarin Professor Marianne Constable Professor Hans Sluga Summer 2017 Abstract Difference and Disease in Three Platonic Dialogues: Gorgias, Phaedo, and Timaeus by Chiara Teresa Ricciardone Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric with the designated emphasis in Critical Theory University of California, Berkeley Professors G.R.F. Ferrari and Ramona Naddaff, Co-chairs This study traces a persistent connection between the image of disease and the concept of difference in Plato’s Gorgias, Phaedo, and Timaeus. Whether the disease occurs in the body, soul, city, or cosmos, it always signals an unassimilated difference that is critical to the argument. I argue that Plato represents—and induces—diseases of difference in order to produce philosophers, skilled in the art of differentiation. Because his dialogues intensify rather than cure difference, his philosophy is better characterized as a “higher pathology” than a form of therapy. An introductory section on Sophist lays out the main features of the concept of difference- in-itself and concisely presents its connection to disease. The main chapters examine the relationship in different realms. In the first chapter, the problem is moral and political: in the Gorgias, rhetoric is a corrupting force, while philosophy purifies the city and soul by drawing distinctions.