COMMISSION DECISION of 30 April 1999 Relating to A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Positioning at Maersk Line

Delft University of Technology Civil Engineering Transport & Planning Optimization of modal shift and container (re-)positioning at Maersk Line Author: Erik Altena April, 2013 Colophon Study: Delft University of Technology Master Transport & Planning Faculty of Civil Engineering Subject: Optimization of modal shift and container (re-)positioning at Maersk Line Author: Erik Altena [email protected] Supervisors: Thesis professor Prof. dr. R.A. Zuidwijk [email protected] TU Delft Thesis supervisor: Dr. J.M. Vleugel [email protected] TU Delft Extern 1 Drs. Ing. R.H.C. Klijnhout [email protected] Maersk Line Extern 2 Dr. J.W. Konings [email protected] TU Delft Graduation coordinator Ir. P.B.L. Wiggenraad [email protected] TU Delft 2 Acknowledgment This report is the final result of the Master Transport & Planning at Delft University of Tech- nology. The study was done at Maersk Line Netherlands - department Inland Operations - in Rotterdam. The research direction of modal shift and container (re-)positioning is chosen in collaboration between the TU Delft, Maersk Line and myself. The aim of the research is contribute to the field of research and support Maersk Line with recommendations to improve their business processes. First of all my thanks go to the graduation committee. Prof. dr. R.A. Zuidwijk for taking the role as thesis professor and assistance with the mathematical modeling. Drs. Ing. R.H.C. Klijnhout as daily supervisor at Maersk Line with great help in every phase of the thesis project. Dr. J.M. Vleugel as daily supervisor at Delft University of Technology especially with his ac- curacy in reading texts, following the planning and as great motivator in the weekly meetings. -

Maersk Line and the Future of Container Shipping

9-712-449 REV: JUNE 1, 2012 FOREST L. REINHARDT RAMON CASADESUS - MASANELL FREDERIK NELLEMANN Maersk Line and the Future of Container Shipping There is a difference between just moving a container and moving it in the most sustainable, easy, and reliable way. And that difference is worth something to our customers. — Morten Engelstoft, Chief Operating Officer, Maersk Line, 2012 It was a cold February afternoon in 2012 as Søren Skou looked out the window of his office across the Copenhagen waterfront. Skou had just recently been promoted to become CEO of Maersk Line, the world’s largest container shipping company, and the flagship company of the Danish conglomerate A.P. Moller-Maersk Group. He was taking the reins at a difficult time: the sluggish global economy had severely depressed container rates, while fuel prices were still at record levels. On some trade routes, the company—like its competitors—wasn’t even meeting the costs of deploying its large and expensive container ships. Skou was confident that the company would pull through. After all, it had recently completed a successful turnaround following the Maersk Line’s first ever annual loss in 2009 and the Group benefited from a diverse holding of activities, which included an oil and gas business. However, Skou needed to assess whether Maersk Line was headed in the right direction, both to be able to compete in this slower market but also once the economy, and global trade, picked up. In 2010 the company had decided to focus on three differentiators to help it maintain its position as the global leader: reliability, ease-of-doing business, and environmental performance. -

Federal Register/Vol. 80, No. 117/Thursday, June 18, 2015/Notices

34908 Federal Register / Vol. 80, No. 117 / Thursday, June 18, 2015 / Notices Office, Western District of Oklahoma Agreements at (202) 523–5793 or Parties: Maersk Line A/S DBA (via email). [email protected]. Sealand; APL Co. Pte Ltd.; American [FR Doc. 2015–15065 Filed 6–17–15; 8:45 am] Agreement No.: 011753–004. President Lines, Ltd.. BILLING CODE 6712–01–P Title: Hoegh Autoliners/EUKOR Filing Party: Wayne R. Rohde, Esq.; Space Charter Agreement. Cozen O’ Connor; 1627 I Street NW., Parties: Hoegh Autoliners AS and Suite 1100; Washington, DC 20006– EUKOR Car Carriers, Inc. FEDERAL DEPOSIT INSURANCE 4007. Filing Party: Wayne R. Rohde, Esq.; CORPORATION Synopsis: The agreement is a vessel Cozen O’Connor; 1627 I Street NW., sharing agreement in the trade between Suite 1100; Washington, DC 20036. Sunshine Act Meeting the U.S. East Coast on the one hand, and Synopsis: The amendment expands Panama and Colombia on the other. Pursuant to the provisions of the the geographic scope of the agreement to ‘‘Government in the Sunshine Act’’ (5 include the trade from the U.S. West Agreement No.: 012347. U.S.C. 552b), notice is hereby given that Coast to Japan, China and the Republic Title: NYK/‘‘K’’ Line Space Charter at 10:15 a.m. on Tuesday, June 16, 2015, of Korea, and updates the addresses of Agreement. the Board of Directors of the Federal the parties. Parties: Nippon Yusen Kaisha, Ltd. Deposit Insurance Corporation met in Agreement No.: 012206–002. and Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd. closed session to consider matters Title: Grimaldi/‘‘K’’ Line Space Filing Party: John P. -

Federal Register/Vol. 64, No. 40/Tuesday, March 2, 1999/Notices

Federal Register / Vol. 64, No. 40 / Tuesday, March 2, 1999 / Notices 10147 APL Co. PTE Ltd. between United States Atlantic and Board, are available for immediate Hapag-Lloyd Container Linie GmbH California ports and ports in the inspection at the Federal Reserve Bank Kawasaki Kisen Kaisha, Ltd. United Kingdom, France, Germany, indicated. The application also will be Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Ltd. Belgium, the Netherlands, and available for inspection at the offices of Nippon Yusen Kaisha Scandinavia. the Board of Governors. Interested Orient Overseas Container Line, Inc. Dated: February 25, 1999. persons may express their views in P&O Nedlloyd B.V. writing on the standards enumerated in P&O Nedlloyd Limited By Order of the Federal Maritime Commission. the BHC Act (12 U.S.C. 1842(c)). If the Sea-Land Service, Inc. proposal also involves the acquisition of Bryant VanBrakle, Synopsis: The proposed modification a nonbanking company, the review also revises Article 5.1(d) of the Secretary. includes whether the acquisition of the Agreement to provide for flexibility in [FR Doc. 99±5083 Filed 3±1±99; 8:45 am] nonbanking company complies with the the way the members' tariffs are BILLING CODE 6730±01±M standards in section 4 of the BHC Act. published. Unless otherwise noted, nonbanking Agreement No.: 203±011325±018 activities will be conducted throughout FEDERAL MARITIME COMMISSION Title: Westbound Transpacific the United States. Unless otherwise noted, comments Stabilization Agreement Ocean Freight Forwarder License regarding each of these applications Parties: Applicants American President Lines, Ltd. must be received at the Reserve Bank China Ocean Shipping (Group) Co. -

A.P. Møller - Mærsk A/S

A.P. Møller - Mærsk A/S Annual Report 2016 Esplanaden 50, DK-1098 Copenhagen K / Registration no. 22756214 A.P. Moller - Maersk — Annual Report 2016 CONTENTS DIRECTORS’ REPORT FINANCIALS ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Highlights Consolidated financial Board of Directors 1 statements 2016 Guidance for 2017 Management Board 1 Parent company financial Five year summary statements 2016 Company overview 2 Strategy Statement of the Board of Directors Definition of terms Invested capital and ROIC and the Management Board Company announcements 2016 Financial review of the businesses Independent Auditor’s Report External financial reporting for A.P. Moller - Maersk1 Financial report PAGES 35-104 PAGES 105-115 Q4 2016 financials Risk management Corporate governance Shareholder information PAGES 3-34 The Annual Report for 2016 of A.P. Møller - Mærsk A/S (further referred to as A.P. Moller - Maersk as the consolidated group of companies and A.P. Møller - Mærsk A/S as the parent company) has been prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) as adopted by the EU and further requirements in the Danish Financial Statements Act. Comparative figures Unless otherwise stated, all figures in parenthesis refer to the 1 Part of Directors’ Report corresponding figures for the previous year. 2 Part of Financials 2 / 115 A.P. Moller - Maersk — Annual Report 2016 Contents Directors’ report Highlights / Guidance for 2017 / Five year summary / Strategy / Invested capital and ROIC / Financial review of the businesses / Financial report / Q4 2016 financials Risk management / Corporate governance / Shareholder information / Board of Directors / Management Board / External financial reporting for A.P. Moller - Maersk 3 / 115 A.P. -

A.P. Møller - Mærsk A/S

A.P. Møller - Mærsk A/S Interim Report Q2 2017 Esplanaden 50, DK-1098 Copenhagen K / Registration no. 22756214 A.P. Moller - Maersk — Interim Report Q2 2017 DIRECTORS’ REPORT The Interim Report for Q2 2017 of A.P. Møller - Mærsk A/S (further referred to as A.P. Moller - Maersk as the consolidated group of companies) has been prepared CONTENTS Highlights Q2 2017 in accordance with IAS 34 Interim Financial Reporting, as adopted by the EU and Guidance for 2017 additional Danish disclosure requirements for interim financial reporting of listed Summary financial information companies. Financial review — Transport & Logistics Comparative figures — Energy Unless otherwise stated, all figures in parenthesis refer to the corresponding figures for the same period prior year. Highlights for the first six months of 2017 PAGES 3-30 Forward-looking statements The Interim Report contains forward-looking statements. Such statements are Statement of the Board of Directors subject to risks and uncertainties as various factors, many of which are outside and the Management Board A.P. Moller - Maersk’s control, may cause actual development and results to differ Independent Auditor’s Review Report materially from expectations contained in the Interim Report. on Interim Consolidated Financial Statements PAGES 31-32 FINANCIALS Condensed income statement Condensed statement of comprehensive income Condensed balance sheet Condensed cash flow statement Condensed statement of changes in equity Notes PAGES 33-49 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION Definition of terms PAGES 50-51 2 / 52 A.P. Moller - Maersk — Interim Report Q2 2017 Contents Directors’ report Highlights Q2 2017 / Guidance for 2017 / Summary financial information / Financial review Transport & Logistics / Financial review Energy / Highlights for the first six months of 2017 3 /52 A.P. -

A Literature Review, Container Shipping Supply Chain: Planning Problems and Research Opportunities

logistics Review A Literature Review, Container Shipping Supply Chain: Planning Problems and Research Opportunities Dongping Song School of Management, University of Liverpool, Chatham Street, Liverpool L69 7ZH, UK; [email protected] Abstract: This paper provides an overview of the container shipping supply chain (CSSC) by taking a logistics perspective, covering all major value-adding segments in CSSC including freight logistics, container logistics, vessel logistics, port/terminal logistics, and inland transport logistics. The main planning problems and research opportunities in each logistics segment are reviewed and discussed to promote further research. Moreover, the two most important challenges in CSSC, digitalization and decarbonization, are explained and discussed in detail. We raise awareness of the extreme fragmentation of CSSC that causes inefficient operations. A pathway to digitalize container shipping is proposed that requires the applications of digital technologies in various business processes across five logistics segments, and change in behaviors and relationships of stakeholders in the supply chain. We recognize that shipping decarbonization is likely to take diverse pathways with different fuel/energy systems for ships and ports. This gives rise to more research and application opportunities in the highly uncertain and complex CSSC environment. Citation: Song, D. A Literature Keywords: container shipping supply chain; transport logistics; literature review; digitalization; Review, Container Shipping Supply -

Freight Rates and Maritime Transport Costs

3 As in 2015, the shipping industry faced continued challenges in most segments in 2016, owing to the persistent mismatch between supply capacity and demand. With global demand for seaborne trade remaining uncertain, freight rates continued to be determined by the way supply capacity management was being handled. This chapter covers the development of freight rates and transport costs in 2016 and early 2017, describing relevant developments in maritime markets, namely supply and demand in container ships, dry bulk carriers and tankers. It highlights significant events leading to major freight rate fluctuations, discusses recent industry trends and gives a selective outlook on future developments of freight markets. In particular, the chapter explores the recent trend towards consolidation that developed in the container ship market, both in the form of new mergers and acquisitions, as well as through the emergence of mega liner shipping alliances and their implication on the market. FREIGHT RATES Container freight rates have been very low, and AND MARITIME competition on various trade routes has intensified. Market fundamentals in container shipping improved TRANSPORT for the first time since 2011, mainly as a result of a contraction in supply growth. The dry bulk sector COSTS continued to struggle with existing overcapacity and weak growth in demand, which led to sharp declines in freight rates. Freight rates in all tanker segments went down from the high level of 2015, but were not far from the five-year average across most segments. With regard to total international transport costs, UNCTAD estimates that in 2016 a country spent on average about 15 per cent of the value of its imports on international transport and insurance. -

Maersk Group Strategy and Performance Page 2 Maersk Group

page 1 Maersk Group strategy and performance page 2 Maersk Group • Founded in 1904 • Represented in over 130 countries, employing around 90,000 people • Market capitalisation of around USD 44bn end Q1 2015 Facilitating global containerised trade Maersk Line carries around 14% of all seaborne containers and, together with APM Terminals and Damco, provides infrastructure for global trade. Supporting the global demand for energy The Group is involved with production of oil and gas and other related activities including drilling, offshore, services, towage, and transportation of crude oil and products. Appendix – Q1 2015 page 3 Ambitions • The Group will create value through profitable growth and by creating winning businesses • The Group seeks to improve the Return on Invested Capital by; • Focused and disciplined capex allocation • Portfolio optimization • Performance management • The Group intends to share the value creation by grow dividends in nominal terms and have bought back shares Appendix – Q1 2015 page 4 The Maersk Group Revenue, NOPAT and Invested capital split MAERSK LINE MAERSK OIL APM TERMINALS MAERSK DRILLING APM SHIPPING SERVICES Revenue, FY2014 (%) 56% 18% 9% 4% 12% NOPAT1, FY2014 (%) 42% 20% 16% 9% 4% INVESTED CAPITAL, FY2014 (%) 40% 11% 12% 15% 9% Note 1: Excluding one-offs, unallocated, eliminations and discontinued operations Residual explained by Other businesses Appendix – Q1 2015 page 5 Strategic focus on creating winning businesses Return BELOW WACC in FY 2014 Return ABOVE WACC in FY 2014 Industry Top quartile performance in FY Excl. Brazilian impairment 2014 BU outperform industry – but below WACC return BU outperform industry – and above WACC return NOT Top quartile performance in FY 2014 BU underperform industry and below WACC return BU underperform industry – but above WACC return Source: Industry peer reports, Maersk Group financial reports, like-for-like with peer return calculation. -

Completed Acquisition by AP Møller-Maersk A/S of a 31 Per Cent Interest in DFDS A/S

Completed acquisition by AP Møller-Maersk A/S of a 31 per cent interest in DFDS A/S ME/4563/10 The OFT's decision on reference under section 22 given on 19 July 2010. Full text of the decision published on 26 July 2010. Please note that the square brackets indicate figures or text which have been deleted or replaced in ranges at the request of the parties or third parties for reasons of commercial confidentiality. PARTIES 1. AP Møller-Maersk A/S (APMM) is one of the world's largest shipping companies. It is active in a wide range of activities including intercontinental container shipping, tanker shipping (product tankers, crude oil carriers and gas carriers), shipping terminal services, freight forwarding and the provision of general logistics services. 2. DFDS A/S (DFDS) is a Danish company active in short sea shipping services within Northern Europe. Its activities include container shipping, passenger shipping, terminal services and freight forwarding. TRANSACTION 3. On 17 June 2010 the European Commission (the Commission) announced its approval, subject to commitments, of DFDS' acquisition of Norfolk Holdings BV (Norfolk), a wholly owned subsidiary of APMM.1 As part of the consideration for Norfolk, APMM received shares in DFDS equivalent to around 31 per cent of DFDS' share capital. The transfer of shares took place within the context of a rights issue of new shares by DFDS which completed on 12 July 2010. Apart from APMM receiving shares directly 1 COMP/M.5756 DFDS/Norfolk. 1 from DFDS Tor Line Holding AB (a subsidiary of DFDS), which account for less than one per cent of DFDS' issued shares, the transfer of shares was between Vesterhavet Holding A/S (Vesterhavet, a subsidiary of the shipping company Lauritzen Fonden) and APMM (the Transaction). -

Global Maritime Networks. the Case of Maersk A

Global Maritime Networks. The case of Maersk A. Fremont To cite this version: A. Fremont. Global Maritime Networks. The case of Maersk. Journal of Transport Geography, Elsevier, 2007, Vol15,n6, p431-442. hal-00505949 HAL Id: hal-00505949 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00505949 Submitted on 31 Aug 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Journal of Transport Geography, Vol 15, issue 6 November 2007, Pp 431-442 Doi:10.1016/j.trangeo.2007.01.005 copyright©2007 Elsevier Ltd All reserved. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/09666923 Global maritime networks. The case of Maersk Dr Antoine FREMONT The French National Institute for Transport and Safety Research (INRETS) [email protected] Tel: 00 33 1 47 40 72 24 Fax: 00 33 1 45 47 55 06 Abstract Two contrasting approaches to the provision of maritime services are frequently presented: one based on direct port to port services, the other characterised by a hub and spoke network. We demonstrate there is no contradiction between these two models, that in fact they are complementary. Integrating direct services and with a hub structure is necessary for assuring a wider geographical coverage. -

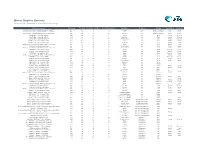

Direct Shipline Services to Be Used As a Guide; Confirm with the Ocean Carrier Upon Booking Your Freight

Direct Shipline Services To be used as a guide; confirm with the ocean carrier upon booking your freight. Service_short_name Frequency Terminal Export_Transit_Time Import_Transit_Time Port_Name Tradelane Country Depart_Day Arrive_day MSC/Maersk Line -- Hamburg Sud/Safmarine - America Express-AMEX Weekly PMT 22 32 Port Elizabeth ZA Africa Republic of South Africa Sunday Saturday MSC/Maersk Line -- Hamburg Sud/Safmarine - America Express-AMEX Weekly PMT 26 26 Durban Africa Republic of South Africa Sunday Saturday MSC/Maersk Line -- Hamburg Sud/Safmarine - America Express-AMEX Weekly PMT 33 21 Cape Town Africa Republic of South Africa Sunday Saturday OCEAN Alliance - Taiwan Strait-TWS/AUE Weekly VIG 31 37 Xiamen Asia China Thursday Wednesday OCEAN Alliance - Taiwan Strait-TWS/AUE Weekly VIG 35 33 Hong Kong Asia China Thursday Wednesday OCEAN Alliance - Taiwan Strait-TWS/AUE Weekly VIG 36 32 Yantian Shenzhen Asia China Thursday Wednesday THE Alliance - North America East Coast-EC1 Weekly NIT 36 39 Xiamen Asia China Monday Saturday THE Alliance - North America East Coast-EC1 Weekly NIT 37 37 Hong Kong Asia China Monday Saturday 2M Alliance -- Alianca/Hamburg Sud/HMM/Safmarine/Zim - TP16/Emerald Weekly VIG 37 38 Xiamen Asia China Saturday Friday THE Alliance - North America East Coast-EC1 Weekly NIT 38 36 Yantian Shenzhen Asia China Monday Saturday 2M Alliance -- Alianca/Hamburg Sud/HMM/Safmarine/Zim - TP16/Emerald Weekly VIG 40 35 Yantian Shenzhen Asia China Saturday Friday OCEAN Alliance - Manhattan Bridge-AWE2 Weekly VIG 40 35 Qingdao Asia