Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kenya Gazette

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaperat the G.P.O.) Vol. CXX—No. 64 NAIROBI, 31st May, 2018 Price Sh. 60 CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICES GAZETTE NOTICES—{Contd.} PAGE PAGE Establishment of Taskforce on Building Bridges to The Environmental Managementand Co-ordination Act— Unity AdViSOTY 0... ecscsssesccssssessessecssssseecsesseeeesnnseseenes 1658 Environmental Impact Assessment Study Report........... 1693-1695 of County Government Notices ......scssscsssssssseccnsereeceneeeneniees 1658, 1679-1692 The Labour Relations Act— Application for Registration 1695 ae .. Trade Union The Land Registration Act—Issue of Provisional Certificates, etc....... 1658-1672 The Records Disposal (Courts) Rules—Intended . Destruction of Court Records «0.0... ssssssecsesssesseeresssaseeees 1695-1696 The Land Act—Intention to Acquire Land, etc............0000 1673-1676 . oo, . Disposal of Uncollected Goods ......cccsecsecsetsesnsessneessienssees 1696 The Geologists Registration Act—Registered Geologists ... 1676-1679 1696-1702 . LossofPolicies. The Physical Planning Act—Completion of Part 1702-1703 Development Plains........csssccssecseessersteesneeneeesecennesssensaenane 1693 Change of Names .......ssccccsceeesesseeeeetenererensseseseansesseceeess [1657 1658 THE KENYA GAZETTE 31st May, 2C 1% CORRIGENDA (e) shall outline the policy, administrative reform proposals, and IN Gazette Notice No. 2874 of 2018, amend the Cause No.printed implementation modalities for each identified challenge area; as “55 of 2017”to read “55 of 2018”. (f) shall consider and propose appropriate mechanisms ; for coordination, collaboration and cooperation amonginstitutions to bring about the sought changes; IN Gazette Notice No. 4246 of 2018, Cause No. 72 of 2018, amend the deceased's name printed as “Teresia Wairimu” to read “Teresia (g) shall pay special attention to making practical interventions Wairimu Njai”. that will entrench honourable behaviour, integrity and inclusivity in leading social sectors; IN Gazette Notice No. -

African Journal of Co-Operative Development and Technology ASSESSMENT of ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION and WATER QUALITY in SOUTHERN

African Journal of Co-operative Development and Technology ASSESSMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION AND WATER QUALITY IN SOUTHERN VIHIGA HILLS OBOKA A. Wycliffe1 & OTHOO O. Calvince2 1The Co-operative University of Kenya, School of Cooperatives and Community Development, P.O. Box 24814- 00502 Karen – Nairobi, Kenya, Email: [email protected], or 2The Co-operative University of Kenya, School of Cooperatives and Community Development, P.O. Box 24814- 00502 Karen – Nairobi, Kenya, Email: [email protected] Abstract Southern Vihiga hills present a case of an intriguing history of land degradation in Kenya that has over the years defied all efforts to address. In 1957, as a measure to curb environmental degradation in southern Vihiga, the colonial government through the legal notice number 266 of the Kenya gazette supplement number 28 established Maragoli Hills Forest without the acceptance by the local communities. The forest was over time degraded, and completely destroyed in 1990s. Efforts to rehabilitate the forest have continually been frustrated by the local community. The study set out to determine the extent of environmental degradation; and establish water quality in streams originating southern Vihiga hills. Data for the study was collected using GPS surveys; photography; high temporal resolution satellite imagery; and interviews. Data on environmental degradation was analyzed through ArcGIS 10.3.1. Analysis of biological and physiochemical parameters of water was undertaken at the government chemist in Kisumu. The study found total loss of forest cover on Edibwongo Hill (Maragoli forest), with extensive areas of bare surfaces, and gulleys. The study also found very high population of Coliform and E.Coli in water in all the three streams sampled in both dry and wet seasons; and very high turbidity; water color; and iron (Fe) concentrations in water from the sampled streams. -

The Case of East Bunyore Location, Emuhaya Division, Vihiga District, Kenya

INSTITUTE OF AFRICAN STUDIES (I.A.S) UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI (U.O.N) RESEARCH PROBLCM THE INFLUENCE OF THE FAMILY ON SCHOOL DROP-OUT AMONG THE YOUTH: THE CASE OF EAST BUNYORE LOCATION, EMUHAYA DIVISION, VIHIGA DISTRICT, KENYA. A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS IN ANTHROPOLOGY. IN THE INSTITUTE OF AFRICAN STUDIES OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI IN THE 1996/97 ACADEMIC YEAR. University of NAIROBI Library UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI INST. OF AFRICAN £TUDIE* I IRRAK-v BY: OKUSI KETRAY SUPERVISOR: DR. LEUNITA A. MURULI DECLARATION This is my original work and has not been presented by anybody anywhere for examination. SIGNATURE: OKUSI KETRAY (N06/1421/92) This dissertation has been submitted for examination with my approval as a University supervisor. SIGNATURE: a (c ) % 1 1 3 * Dr. Leunita A. Muruli University Supervisor I . A. S 1 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my father, Mr. Jairus Okusi who injected in me a sense of hard work, honesty, obedience and above all discipline and respect for others. 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I acknowledge the unrelenting support and intellectual advice extended to me by my supervisor, Dr. Leunita A. Muruli. I thank Mr. Nyamongo and Dr. Nang'endo for their constructive criticism and suggestions during the course of my research. I also thank my fellow classmates for their encouragement. I am indebted to the Institute staff both academic and non-academic for the invaluable support. Special thanks go to the school drop-outs and key informants who without their co-operation this research would not have been a success. -

N0n-Governmental Organizations, the State and the Politics of Rural

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS, THE STATE AND THE POLITICS OF RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN KENYA WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO WESTERN PROVINCE A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of RHODES UNIVERSITY by FRANK KHACHINA MATANGA November 2000 ABSTRACT In recent decades, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) have increasingly taken on development and political roles in Africa. This has partly been attributed to the New Policy Agenda (NPA) mounted by the international donors. The NPA is predicated on neo-liberal thinking advocating for an enlarged development role for the private sector and a minimalist state. This relatively new shift in development thought has been motivated by the declining capacity of the African state to deliver development and guarantee a liberal political system. This study, therefore, set out to empirically examine whether NGOs are capable of effectively playing their new-found development and political roles. The study was based on Kenya with the Western Province constituting the core research area. The fact that the Kenyan state has been gradually disengaging from the development process has created a vacuum of which the NGOs have attempted to fill. Equally important has been the observation that, for the greater part of the post-colonial period, the state has been largely authoritarian and therefore prompting a segment of civil society to take on political roles in an effort to force it to liberalize and democratize. Urban NGOs in particular, have been the most confrontational to the state with some remarkable success. -

Interruption of Electricity Supply

ELGEYO MARAKWET COUNTY Interruption of AREA: EMSEA, BIRETWO DATE: Thursday 21.05.2020 TIME: 9.00 A.M. - 5.00 P.M. Emsea, Chegilet, Biretwo, Kebulwo, Muskut, Cheptebo, Sego & Electricity Supply adjacent customers. Notice is hereby given under rule 27 of the Electric Power Rules That the electricity supply will be interrupted as here under: WESTERN REGION (It is necessary to interrupt supply periodically in order to facilitate maintenance and upgrade of power lines to the network; to connect new customers or to replace power lines during road SIAYA COUNTY construction, etc.) AREA: MUR MALANGA MKT, TINGWANGI, ANDURO DATE: Saturday 16.05.2020 TIME: 9.00 A.M. - 3.00 P.M. Anduro Pri Sch, Randago, Nyanginja Youth Polytechnic, Matera Sec Sch, Rakuom Pri Sch, Mur Malanga Mkt, Ambrose Adeya Sec Sch, Mugane Pri NAIROBI NORTH REGION Sch, Tingwangi Airtel Booster, Sulwe Estate & adjacent customers. NAIROBI COUNTY VIHIGA COUNTY AREA: GIKOMBA FEEDER AREA: KIMA MKT, EMUSIRE, EMUHAYA DATE: Sunday 17.05.2020 TIME: 8.00 A.M. - 5.00 P.M. DATE: Monday 18.05.2020 TIME: 9.00 A.M. - 11.00 A.M. Nacico Plaza, Machakos Country Bus, Kenya Cold Storage, KMC, Equity Maseno Water, Mwichio Mkt, Kima Mission, Kima Mkt, Esikulu Mkt, Ematioli, Bank, COTU, Pumwani Rd, Kombo Munri Rd, Ismailia Flats, Digo Rd, Kariako Emanyinya, Emusire H/c, Esunza, Emuhaya H/c, Emuhaya CC Ofice, Ibubi, Flats, Ziwani Est, Habib, Starehe DO Offices, Gikomba Mkt, Starehe Boys, Wemilabi Safaricom Booster, Maseno Coptic Hosp, Ebusakami & adjacent Quarry Rd, Whole of Kariako, Gikomba & adjacent customers. customers. AREA: MUHUDU MKT, SHIANDA VILLAGE, MUYELE NAIROBI WEST REGION DATE: Tuesday 19.05.2020 TIME: 8.30 A.M. -

Safe Motherhood Demonstration Project, Western Province: Final Report

Population Council Knowledge Commons Reproductive Health Social and Behavioral Science Research (SBSR) 2004 Safe Motherhood Demonstration Project, Western Province: Final Report Charlotte E. Warren Population Council Wilson Liambila Population Council Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh Part of the Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, International Public Health Commons, and the Maternal and Child Health Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Warren, Charlotte E. and Wilson Liambila. 2004. "Safe Motherhood Demonstration Project, Western Province: Final Report," Final report. Nairobi: Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health, University of Nairobi, and Population Council. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Population Council. SAFE MOTHERHOOD DEMONSTRATION PROJECT WESTERN PROVINCE Approaches to providing quality maternal care in Kenya Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health University of Nairobi SAFE MOTHERHOOD DEMONSTRATION PROJECT WESTERN PROVINCE FINAL REPORT Population Council Charlotte Warren Wilson Liambila December 2004 The Population Council is an international, nonprofit, nongovernmental institution that seeks to improve the well-being and reproductive health of current and future generations around the world and to help achieve a humane, equitable, and sustainable balance between people and resources. The Council conducts biomedical, social science, and public health research and helps build research capacities in developing countries. Established in 1952, The Council is governed by an international board of trustees. Its New York headquarters supports global network of regional and country offices. Sub-Saharan Africa Region, Nairobi Office Genereal Accident Insurance House Ralph Bunche Road P.O. -

Kakamega County Integrated Development Plan, 2013-2017 I

REPUBLIC OF KENYA THE COUNTY GOVERNMENT OF KAKAMEGA KENYA THE FIRST COUNTY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2013-2017 First Kakamega County Integrated Development Plan, 2013-2017 i COUNTY VISION AND MISSION Vision A wealthy and vibrant county offering high quality services to its residents Mission To improve the welfare of the people of Kakamega County through formulation and implementation of all-inclusive multi-sectoral policies First Kakamega County Integrated Development Plan, 2013-2017 ii County Government of Kakamega All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the County Government of Kakamega. ALL ENQUIRIES ABOUT THIS PLAN SHOULD BE DIRECTED TO: The County Secretary P.O. Box 36-50100 Kakamega Website: www.kakamegacounty.go.ke Photo 1:The First Kakamega County Executive Committee Members-2013 First Kakamega County Integrated Development Plan 2013-2017 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS COUNTY VISION AND MISSION ........................................................................ II LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................ VI LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................ VII ABBREVIATION AND ACRONYMS ................................................................... IX FOREWORD...................................................................................................... -

The Construction of the Abanyole Perceptions on Death Through Oral Funeral Poetry Ezekiel Alembi

Ezekiel Alembi The Construction of the Abanyole Perceptions on Death Through Oral Funeral Poetry Ezekiel Alembi The Construction of the Abanyole Perceptions on Death Through Oral Funeral Poetry Cover picture: Road from Eluanda to Ekwanda. (Photo by Lauri Harvilahti). 2 The Construction of the Abanyole Perceptions on Death Through Oral Funeral Poetry ISBN 952-10-0739-7 (PDF) © Ezekiel Alembi DataCom Helsinki 2002 3 DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to the memory of my late parents: Papa Musa Alembi Otwelo and Mama Selifa Moche Alembi and to my late brothers and sisters: Otwelo, Nabutsili, Ongachi, Ayuma and George. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 PROLOGUE 9 PART ONE: INTRODUCTION 12 CHAPTER 1: RESEARCH THEME, SIGNIFICANCE AND THEORETICAL APPROACH 14 1.1 Theme and Significance of The Study 14 1.1.1 Focus and Scope 14 1.1.2 ResearchQuestions 15 1.1.3 Motivation for Studying Oral Funeral Poetry 15 1.2 Conceptual Model 18 1.2.1 Choosing from the Contested Theoretical Terrain 18 1.2.2 Ethnopoetics 19 1.2.2.1 Strands of Ethnopoetics 20 1.2.3 Infracultural Model in Folklore Analysis 22 CHAPTER 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 25 2.1 Introduction 25 2.2 Trends and Issues in African Oral Literature 25 2.2.1 Conceptualization 25 2.2.2 The Pioneer Phase 26 2.2.3 The Era of African Elaboration and Formulation 28 2.2.4 Consolidation and Charting the Future 31 2.3 Trends and Issues in African Oral Poetry 33 2.3.1 The Controversy on African Poetry: Does Africahave Poetry Worth Studying? 33 2.3.2 The Thrust and Dynamics of Research -

Author Guidelines for 8

A BIOGRAPHY OF MOSES BUDAMBA MUDAVADI, 1923 - 1989 By CHARLES KARANI Volume 28, 2016 ISSN (Print & Online): 2307-4531 © IJSBAR THESIS PUBLICATION www.gssrr.org IJSBAR research papers are currently indexed by: © IJSBAR THESIS PUBLICATION www.gssrr.org A BIOGRAPHY OF MOSES BUDAMBA MUDAVADI, 1923 - 1989 Copyright © 2016 by CHARLES KARANI All rights reserved. No part of this thesis may be produced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission of the author. ISSN(online & Print) 2307-4531 The IJSBAR is published and hosted by the Global Society of Scientific Research and Researchers (GSSRR). Members of the Editorial Board Editor in chief Dr. Mohammad Othman Nassar, Faculty of Computer Science and Informatics, Amman Arab University for Graduate Studies, Jordan, [email protected] , 00962788780593 Editorial Board Prof. Dr. Felina Panas Espique, Dean at School of Teacher Education, Saint Louis University, Bonifacio St., Baguio City, Philippines. Prof. Dr. Hye-Kyung Pang, Business Administration Department, Hallym University, Republic Of Korea. Prof. Dr. Amer Abdulrahman Taqa, basic science Department, College of Dentistry, Mosul University, Iraq. Prof. Dr. Abdul Haseeb Ansar, International Islamic University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Dr. kuldeep Narain Mathur, school of quantitative science, Universiti Utara, Malaysia Dr. Zaira Wahab, Iqra University, Pakistan. Dr. Daniela Roxana Andron, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, Romania. Dr. Chandan Kumar Sarkar, IUBAT- International University of Business Agriculture and Technology, Bangladesh. Dr. Azad Ali, Department of Zoology, B.N. College, Dhubri, India. Dr. Narayan Ramappa Birasal, KLE Society’s Gudleppa Hallikeri College Haveri (Permanently affiliated to Karnatak University Dharwad, Reaccredited by NAAC), India. Dr. -

Postal Codes20-15

POST CODES FOR ALL POST OFFICES PLEASE INCLUDE THE POST CODES BEFORE SENDING YOUR LETTER NAIROBI CITY OFFICES POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE 00515 BURUBURU 40101 AHERO 20115 EGERTON 2 0157 KABARAK 2 0501 KEEKOROK 9 0111 KIVUNGA 8 0200 MALINDI 9 0128 MTITU ANDEI 4 0632 NYAMONYE 4 0308 SINDO 30101 AINABKOI 90139 EKALAKALA 7 0300 MANDERA 8 0117 MTOPANGA 2 0423 SIONGIROI 00200 CITY SQUARE 3 0400 KABARNET 4 0413 KEHANCHA 3 0305 KOBUJOI 4 0333 NYANDHIWA 00516 DANDORA 40139 AKALA 20102 ELBURGON 3 0401 KABARTONJO 4 0301 KENDU BAY 9 0108 KOLA 6 0101 MANYATTA 8 0109 MTWAPA 4 0126 NYANGANDE 5 0208 SIRISIA 00610 EASTLEIGH 50244 AMAGORO 20103 ELDAMA RAVINE 9 0205 KABATI 0 1020 KENOL 4 0102 KOMBEWA 5 0300 MARAGOLI 5 0423 MUBWAYO 4 0127 NYANGORI 4 0109 SONDU 00521 EMBAKASI 20424 AMALO (FORMERLY 3 0100 ELDORET 2 0114 KABAZI 4 0211 KENYENYA 4 0103 KONDELE 1 0205 MARAGUA 1 0129 MUGUNDA 4 0502 NYANSIONGO 4 0110 SONGHOR 00500 ENTERPRISE ROAD OLOOMIRANI) 7 0301 ELWAK 2 0201 KABIANGA 2 0200 KERICHO 1 0234 KORA 2 0600 MARALAL 4 0107 MUHORONI 4 0514 NYARAMBA 2 0205 SOSIOT 00601 GIGIRI 50403 AMUKURA 9 0121 EMALI 3 0303 KABIYET 2 0131 KERINGET 4 0104 KORU 8 0113 MARIAKANI 4 0409 MUHURU BAY 4 0402 NYATIKE 2 0406 SOTIK 00100 G.P.O NAIROBI 40309 ASUMBI 6 0100 EMBU 3 0601 KACHELIBA 4 0202 KEROKA 4 0332 KOSELE 3 0403 MARIGAT 5 0225 MUKHE 1 0100 NYERI 2 0319 SOUTH-KINANGOP 00101 JAMIA 00204 ATHI RIVER 5 0314 EMUHAYA 4 0223 KADONGO 1 0300 KERUGOYA 5 0117 KOYONZO 6 0408 MARIMA 1 0103 MUKURWEINI 4 0611 NYILIMA 3 0105 SOY 00501 J.K.I.A. -

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

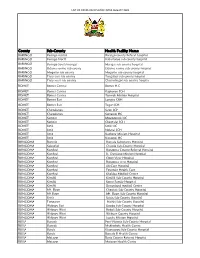

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye -

Logoli Women of Western Kenya Speak:Needs and Means

t LOGOLI WOMEN OF WESTERN KENYA SPEAK: NEEDS AND MEANS by / Judith M. Abwunza i University of NAIROBI Library A Thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Toronto ® Judith M. Abwunza 1991 o / S'% . - W oA % % > / ABSTRACT Logoii Women of Western Kenya Speak: Needs And Means Judith M. Abwunza University of Toronto Department of Anthropology The research on women's power in collective and capitalist structures recognises the important economic position of women. Research in Maragoli, Kenya, shows that women's work is not universally confined to the domestic sphere, nor is gender inequality in productive relations a result of the eclipse of communal and family-based production and property ownership. Women believe gender / inequality is increasing in Maragoli and are resisting. Logoii women attribute the trend to increasing gender inequality to men's actions in entrenching traditional cultural values of patriarchal ideology which serve to reduce and deny women's growing productive role and value. Maragoli women are not controlled by patriarchal ideology although these values are part of the cultural rhetoric. In Maragoli, women assume a posture of ideological and institutional acceptance attached to "the Avalogoli way" as deliberate social action while recognising that "today life is not fair to women". They are producers of both use and exchange value in the collective and capitalist structures, ii extending "home work” responsibilities to "outside work" using cultural avenues to power. Their skills are generated within the collectivity through the accumulation of information and influence which accords them a culturally- valued reputation as "good Logoli wives".