Spatial Land Use Management Strategy on Sustainable

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Kenya Gazette

THE KENYA GAZETTE Published by Authority of the Republic of Kenya (Registered as a Newspaperat the G.P.O.) Vol. CXX—No. 64 NAIROBI, 31st May, 2018 Price Sh. 60 CONTENTS GAZETTE NOTICES GAZETTE NOTICES—{Contd.} PAGE PAGE Establishment of Taskforce on Building Bridges to The Environmental Managementand Co-ordination Act— Unity AdViSOTY 0... ecscsssesccssssessessecssssseecsesseeeesnnseseenes 1658 Environmental Impact Assessment Study Report........... 1693-1695 of County Government Notices ......scssscsssssssseccnsereeceneeeneniees 1658, 1679-1692 The Labour Relations Act— Application for Registration 1695 ae .. Trade Union The Land Registration Act—Issue of Provisional Certificates, etc....... 1658-1672 The Records Disposal (Courts) Rules—Intended . Destruction of Court Records «0.0... ssssssecsesssesseeresssaseeees 1695-1696 The Land Act—Intention to Acquire Land, etc............0000 1673-1676 . oo, . Disposal of Uncollected Goods ......cccsecsecsetsesnsessneessienssees 1696 The Geologists Registration Act—Registered Geologists ... 1676-1679 1696-1702 . LossofPolicies. The Physical Planning Act—Completion of Part 1702-1703 Development Plains........csssccssecseessersteesneeneeesecennesssensaenane 1693 Change of Names .......ssccccsceeesesseeeeetenererensseseseansesseceeess [1657 1658 THE KENYA GAZETTE 31st May, 2C 1% CORRIGENDA (e) shall outline the policy, administrative reform proposals, and IN Gazette Notice No. 2874 of 2018, amend the Cause No.printed implementation modalities for each identified challenge area; as “55 of 2017”to read “55 of 2018”. (f) shall consider and propose appropriate mechanisms ; for coordination, collaboration and cooperation amonginstitutions to bring about the sought changes; IN Gazette Notice No. 4246 of 2018, Cause No. 72 of 2018, amend the deceased's name printed as “Teresia Wairimu” to read “Teresia (g) shall pay special attention to making practical interventions Wairimu Njai”. that will entrench honourable behaviour, integrity and inclusivity in leading social sectors; IN Gazette Notice No. -

N0n-Governmental Organizations, the State and the Politics of Rural

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) NON-GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS, THE STATE AND THE POLITICS OF RURAL DEVELOPMENT IN KENYA WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO WESTERN PROVINCE A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY of RHODES UNIVERSITY by FRANK KHACHINA MATANGA November 2000 ABSTRACT In recent decades, Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) have increasingly taken on development and political roles in Africa. This has partly been attributed to the New Policy Agenda (NPA) mounted by the international donors. The NPA is predicated on neo-liberal thinking advocating for an enlarged development role for the private sector and a minimalist state. This relatively new shift in development thought has been motivated by the declining capacity of the African state to deliver development and guarantee a liberal political system. This study, therefore, set out to empirically examine whether NGOs are capable of effectively playing their new-found development and political roles. The study was based on Kenya with the Western Province constituting the core research area. The fact that the Kenyan state has been gradually disengaging from the development process has created a vacuum of which the NGOs have attempted to fill. Equally important has been the observation that, for the greater part of the post-colonial period, the state has been largely authoritarian and therefore prompting a segment of civil society to take on political roles in an effort to force it to liberalize and democratize. Urban NGOs in particular, have been the most confrontational to the state with some remarkable success. -

Interruption of Electricity Supply

ELGEYO MARAKWET COUNTY Interruption of AREA: EMSEA, BIRETWO DATE: Thursday 21.05.2020 TIME: 9.00 A.M. - 5.00 P.M. Emsea, Chegilet, Biretwo, Kebulwo, Muskut, Cheptebo, Sego & Electricity Supply adjacent customers. Notice is hereby given under rule 27 of the Electric Power Rules That the electricity supply will be interrupted as here under: WESTERN REGION (It is necessary to interrupt supply periodically in order to facilitate maintenance and upgrade of power lines to the network; to connect new customers or to replace power lines during road SIAYA COUNTY construction, etc.) AREA: MUR MALANGA MKT, TINGWANGI, ANDURO DATE: Saturday 16.05.2020 TIME: 9.00 A.M. - 3.00 P.M. Anduro Pri Sch, Randago, Nyanginja Youth Polytechnic, Matera Sec Sch, Rakuom Pri Sch, Mur Malanga Mkt, Ambrose Adeya Sec Sch, Mugane Pri NAIROBI NORTH REGION Sch, Tingwangi Airtel Booster, Sulwe Estate & adjacent customers. NAIROBI COUNTY VIHIGA COUNTY AREA: GIKOMBA FEEDER AREA: KIMA MKT, EMUSIRE, EMUHAYA DATE: Sunday 17.05.2020 TIME: 8.00 A.M. - 5.00 P.M. DATE: Monday 18.05.2020 TIME: 9.00 A.M. - 11.00 A.M. Nacico Plaza, Machakos Country Bus, Kenya Cold Storage, KMC, Equity Maseno Water, Mwichio Mkt, Kima Mission, Kima Mkt, Esikulu Mkt, Ematioli, Bank, COTU, Pumwani Rd, Kombo Munri Rd, Ismailia Flats, Digo Rd, Kariako Emanyinya, Emusire H/c, Esunza, Emuhaya H/c, Emuhaya CC Ofice, Ibubi, Flats, Ziwani Est, Habib, Starehe DO Offices, Gikomba Mkt, Starehe Boys, Wemilabi Safaricom Booster, Maseno Coptic Hosp, Ebusakami & adjacent Quarry Rd, Whole of Kariako, Gikomba & adjacent customers. customers. AREA: MUHUDU MKT, SHIANDA VILLAGE, MUYELE NAIROBI WEST REGION DATE: Tuesday 19.05.2020 TIME: 8.30 A.M. -

Safe Motherhood Demonstration Project, Western Province: Final Report

Population Council Knowledge Commons Reproductive Health Social and Behavioral Science Research (SBSR) 2004 Safe Motherhood Demonstration Project, Western Province: Final Report Charlotte E. Warren Population Council Wilson Liambila Population Council Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledgecommons.popcouncil.org/departments_sbsr-rh Part of the Demography, Population, and Ecology Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, International Public Health Commons, and the Maternal and Child Health Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Recommended Citation Warren, Charlotte E. and Wilson Liambila. 2004. "Safe Motherhood Demonstration Project, Western Province: Final Report," Final report. Nairobi: Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health, University of Nairobi, and Population Council. This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Population Council. SAFE MOTHERHOOD DEMONSTRATION PROJECT WESTERN PROVINCE Approaches to providing quality maternal care in Kenya Republic of Kenya Ministry of Health University of Nairobi SAFE MOTHERHOOD DEMONSTRATION PROJECT WESTERN PROVINCE FINAL REPORT Population Council Charlotte Warren Wilson Liambila December 2004 The Population Council is an international, nonprofit, nongovernmental institution that seeks to improve the well-being and reproductive health of current and future generations around the world and to help achieve a humane, equitable, and sustainable balance between people and resources. The Council conducts biomedical, social science, and public health research and helps build research capacities in developing countries. Established in 1952, The Council is governed by an international board of trustees. Its New York headquarters supports global network of regional and country offices. Sub-Saharan Africa Region, Nairobi Office Genereal Accident Insurance House Ralph Bunche Road P.O. -

Kakamega County Integrated Development Plan, 2013-2017 I

REPUBLIC OF KENYA THE COUNTY GOVERNMENT OF KAKAMEGA KENYA THE FIRST COUNTY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2013-2017 First Kakamega County Integrated Development Plan, 2013-2017 i COUNTY VISION AND MISSION Vision A wealthy and vibrant county offering high quality services to its residents Mission To improve the welfare of the people of Kakamega County through formulation and implementation of all-inclusive multi-sectoral policies First Kakamega County Integrated Development Plan, 2013-2017 ii County Government of Kakamega All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the County Government of Kakamega. ALL ENQUIRIES ABOUT THIS PLAN SHOULD BE DIRECTED TO: The County Secretary P.O. Box 36-50100 Kakamega Website: www.kakamegacounty.go.ke Photo 1:The First Kakamega County Executive Committee Members-2013 First Kakamega County Integrated Development Plan 2013-2017 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS COUNTY VISION AND MISSION ........................................................................ II LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................ VI LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................ VII ABBREVIATION AND ACRONYMS ................................................................... IX FOREWORD...................................................................................................... -

Postal Codes20-15

POST CODES FOR ALL POST OFFICES PLEASE INCLUDE THE POST CODES BEFORE SENDING YOUR LETTER NAIROBI CITY OFFICES POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE POST CODE POST OFFICE 00515 BURUBURU 40101 AHERO 20115 EGERTON 2 0157 KABARAK 2 0501 KEEKOROK 9 0111 KIVUNGA 8 0200 MALINDI 9 0128 MTITU ANDEI 4 0632 NYAMONYE 4 0308 SINDO 30101 AINABKOI 90139 EKALAKALA 7 0300 MANDERA 8 0117 MTOPANGA 2 0423 SIONGIROI 00200 CITY SQUARE 3 0400 KABARNET 4 0413 KEHANCHA 3 0305 KOBUJOI 4 0333 NYANDHIWA 00516 DANDORA 40139 AKALA 20102 ELBURGON 3 0401 KABARTONJO 4 0301 KENDU BAY 9 0108 KOLA 6 0101 MANYATTA 8 0109 MTWAPA 4 0126 NYANGANDE 5 0208 SIRISIA 00610 EASTLEIGH 50244 AMAGORO 20103 ELDAMA RAVINE 9 0205 KABATI 0 1020 KENOL 4 0102 KOMBEWA 5 0300 MARAGOLI 5 0423 MUBWAYO 4 0127 NYANGORI 4 0109 SONDU 00521 EMBAKASI 20424 AMALO (FORMERLY 3 0100 ELDORET 2 0114 KABAZI 4 0211 KENYENYA 4 0103 KONDELE 1 0205 MARAGUA 1 0129 MUGUNDA 4 0502 NYANSIONGO 4 0110 SONGHOR 00500 ENTERPRISE ROAD OLOOMIRANI) 7 0301 ELWAK 2 0201 KABIANGA 2 0200 KERICHO 1 0234 KORA 2 0600 MARALAL 4 0107 MUHORONI 4 0514 NYARAMBA 2 0205 SOSIOT 00601 GIGIRI 50403 AMUKURA 9 0121 EMALI 3 0303 KABIYET 2 0131 KERINGET 4 0104 KORU 8 0113 MARIAKANI 4 0409 MUHURU BAY 4 0402 NYATIKE 2 0406 SOTIK 00100 G.P.O NAIROBI 40309 ASUMBI 6 0100 EMBU 3 0601 KACHELIBA 4 0202 KEROKA 4 0332 KOSELE 3 0403 MARIGAT 5 0225 MUKHE 1 0100 NYERI 2 0319 SOUTH-KINANGOP 00101 JAMIA 00204 ATHI RIVER 5 0314 EMUHAYA 4 0223 KADONGO 1 0300 KERUGOYA 5 0117 KOYONZO 6 0408 MARIMA 1 0103 MUKURWEINI 4 0611 NYILIMA 3 0105 SOY 00501 J.K.I.A. -

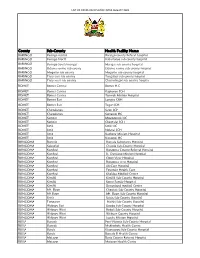

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye -

Parliament of Kenya the Senate

March 13, 2019 SENATE DEBATES 1 PARLIAMENT OF KENYA THE SENATE THE HANSARD Wednesday, 13 th March, 2019 The House met at the Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings, at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Lusaka) in the Chair] PRAYER PAPERS LAID REPORTS ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF VARIOUS COUNTY EXECUTIVES Sen. (Dr.) Langat: Mr. Speaker, Sir, I beg to lay the following Papers on the Table of the Senate today, Wednesday, 13 th March, 2019:- (1) Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statement of the County Executive of Embu for the Year ended 30 th June 2018; (2) Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statement of the County Executive of Nyeri for the Year ended 30 th June 2018; (3) Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statement of the County Executive of Meru for the Year ended 30 th June 2018; (4) Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statement of the County Executive of Kilifi for the Year ended 30 th June 2018; (5) Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statement of the County Executive of Migori for the Year ended 30 th June 2018; (6) Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statement of the County Executive of Kisii for the Year ended 30 th June 2018; (7) Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statement of the County Executive of Marsabit for the Year ended 30 th June 2018; (8) Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statement of the County Executive of Taita Taveta for the Year ended 30 th June 2018; (9) Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statement of the County Executive of Kitui for the Year ended 30 th June 2018; (10) Report of the Auditor-General on the Financial Statement of the County Executive of Tharaka Nithi for the Year ended 30 th June 2018; Disclaimer : The electronic version of the Senate Hansard Report is for information purposes only. -

Vihiga County

VIHIGA COUNTY COUNTY INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2018-2022 COUNTY VISION AND MISSION Vision: To be a model, prosperous and globally competitive county. Mission: To transform Vihiga into a prosperous County and offer quality life to its citizens through formulating and implementing efficient governance systems for sustainable development. ii Table Of Contents County Vision and Mission ........................................................................................................................... II Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................................... III List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................... IV List of Maps................................................................................................................................................. IV Abbreviations and Acronyms ......................................................................................................................... V Foreword .................................................................................................................................................... VII Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................... VIII CHAPTER ONE: COUNTY BACKGROUND INFORMATION .......................................................... -

Shared Drive FP and HIV Integration Report Kenya

Integration of HIV prevention and sexual and reproductive health services in Kenya February 2020 Outline 1. Background 2. Methods 3. Findings 4. Conclusions/Recommendations Background Options in delivery channels can help meet the HIV prevention and family planning (FP) needs of AGYW Maternal Child Health HIV Clinics Pharmacies Community-Based (MCH) and FP (Public + Private) (Private) Delivery Clinics (Public) (Public + Private) Facilities already have Discreet and convenient for human resources and some FP services but PrEP Mobile PrEP delivery has Meet AGYW where they are infrastructure for PrEP, and is more expensive and not proven effective, especially already receiving FP and can add on FP services offered without a prescription for AGYW other services PrEP stigma due to Clinic Dispensaries De-medicalization of PrEP Leverage providers’ time, marketing focused on MSM (Public) and certain contraceptives sync HIV/FP prescriptions & FSW may be a barrier, (pills, injectables, ring, etc.) especially for AGYW Convenient and affordable can provide options for Especially helpful for post- but frequent stock-outs and community-based prevention partum women at risk of HIV Many HIV providers trained can worsen provider delivery for PrEP & FP & unintended pregnancy in FP services already workload Defining HIV/SRH integration and youth-friendly service delivery HIV/SRH Bidirectional synergies in policy, programs and service linkages delivery that meet comprehensive SRH and HIV needs. A subset of HIV/SRH linkages at the service delivery level HIV/SRH joining operational programs to ensure access to SRH and integration HIV services through multiple modalities (e.g. through referral or “one-stop shop” services under one roof). -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface…………………………………………………………………….. i 1. District Context………………………………………………………… 1 1.1. Demographic characteristics………………………………….. 1 1.2. Socio-economic Profile………………………………………….. 1 2. Constituency Profile………………………………………………….. 1 Demographic characteristics………………………………….. 2.1. 1 Socio-economic Profile………………………………………….. 2.2. 1 Electioneering and Political Information……………………. 2.3. 2 1992 Election Results…………………………………………… 2.4. 2 1997 Election Results…………………………………………… 2.5. 2 Main problems……………………………………………………. 2.6. 2 3. Constitution Making/Review Process…………………………… 3 3.1. Constituency Constitutional Forums (CCFs)………………. 3 3.2. District Coordinators……………………………………………. 5 4. Civic Education………………………………………………………… 6 4.1. Phases covered in Civic Education…………………………… 4.2. Issues and Areas Covered……………………………………… 6 6 5. Constituency Public Hearings……………………………………… 7 5.1. Logistical Details…………………………………………………. 5.2. Attendants Details……………………………………………….. 7 5.3. Concerns and Recommendations…………………………….. 7 8 Appendices 31 1. DISTRICT PROFILE Kakamega District is one of 8 districts of the Western Province of Kenya. 1.1 Demographic Characteristics Male Female Total District Population by Sex 290,343 313,079 603,422 Total District Population Aged 18 years & 172,612 172,527 345,139 Below Total District Population Aged Above 18 117,731 140,552 258,283 years Population Density (persons/Km2) 433 1.2 Socio-Economic Profile Kakamega District: • Is one of the most densely populated districts in the province, being ranked 3rd of the 8 districts in the -

Wednesday, 6Th November, 2019 at 2.30 P.M

November 6, 2019 SENATE DEBATES 1 PARLIAMENT OF KENYA THE SENATE THE HANSARD Wednesday, 6th November, 2019 The House met at the Senate Chamber, Parliament Buildings, at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Lusaka) in the Chair] PRAYER MESSAGE FROM THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY PASSAGE OF BILLS BY THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY The Speaker (Hon. Lusaka): Order, Hon. Senators. I wish to report that pursuant to Standing Orders 41(3) and (4), I have received the following Message from the Speaker of the National Assembly regarding the passage by the Assembly of the SACCO Societies (Amendment) Bill, (National Assembly Bills No.1 of 2018) and the Sectional Properties Bill (National Assembly Bills No.23 of 2019). One, the passage of the SACCO Societies (Amendment) Bill, (National Assembly Bills No.1 of 2018): Pursuant to the provisions of the Standing Orders 41(1) and 142 of the National Assembly Standing Orders, I hereby convey the following message from the National Assembly. “WHEREAS, the SACCO Societies (Amendment) Bill, (National Assembly Bills No.1 of 2018) was published vide Kenya Gazette Supplement No.2 of 19th January, 2018, to provide for the registration and licensing of SACCO Societies as deposit taking, savings and credit cooperatives; AND WHEREAS, the National Assembly considered and passed the said Bill without amendments on Wednesday, 9th October, 2019, in the form attached hereto; NOW THEREFORE, in accordance with the provisions of Article 110(4) of the Constitution and Standing Order 41 of the National Assembly Standing Orders, I hereby refer the Bill to the Senate for consideration”. Two, passage of the Sectional Properties Bill (National Assembly Bills No.23 of 2019): Pursuant to the provisions of the Standing Orders 41(1) and 142 of the National Assembly Standing Orders, I hereby convey the following message from the National Assembly.