Guavira Número 6

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feb. 7 to Apr. 30, 2017 Great Hall

Ministry of Culture and Museu de Arte To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Moderna de São Paulo present exhibition that inaugurated Brazilian modernism, Anita Malfatti: 100 Years of Modern Art gathers at FEB. 7 MAM’s Great Hall about seventy different works covering the path of one of the main names in TO Brazilian art in the 20th century. Anita Malfatti’s exhibition in 1917 was crucial to the emergence of the group who would champion modern art in Brazil, so much so that APR. 30, critic Paulo Mendes de Almeida considered her as the “most historically critical character in the 2017 1922 movement.” Regina Teixeira de Barros’ curatorial work reveals an artist who is sensitive to trends and discussions in the first half of the 20th century, mindful of her status and her choices. This exhibition at MAM recovers drawings and paintings by Malfatti, divided into three moments in her path: her initial years that consecrated her as “trigger of Brazilian modernism”; the time she spent training in Paris and her naturalist production; and, finally, her paintings with folk themes. With essays by Regina Teixeira de Barros and GREAT Ana Paula Simioni, this edition of Moderno MAM Extra is an invitation for the public to get to know HALL this great artist’s choices. Have a good read! MASTER SPONSORSHIP SPONSORSHIP CURATED BY REALIZATION REGINA TEIXEIRA DE BARROS One hundred years have gone by since the 3 03 ANITA Exposição de pintura moderna Anita Malfatti [Anita Malfatti Modern Painting Exhibition] would forever CON- MALFATTI, change the path of art history in Brazil. -

Pagu: a Arte No Feminino Como Performance De Si

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS MESTRADO INTERDISCIPLINAR EM PERFORMANCES CULTURAIS LUCIENNE DE ALMEIDA MACHADO PAGU: A ARTE NO FEMININO COMO PERFORMANCE DE SI GOIÂNIA, MARÇO DE 2018. UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS MESTRADO INTERDISCIPLINAR EM PERFORMANCES CULTURAIS LUCIENNE DE ALMEIDA MACHADO PAGU: A ARTE NO FEMININO COMO PERFORMANCE DE SI Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação Interdisciplinar em Performances Culturais, para obtenção do título de Mestra em Performances Culturais pela Universidade Federal de Goiás. Orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Sainy Coelho Borges Veloso. Co-orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Marcela Toledo França de Almeida. GOIÂNIA, MARÇO DE 2018. i ii iii Dedico este trabalho a quem sabe que a pele é fina diante da abertura do peito, que o coração a toca. Por quem sabe que é impossível viver por certos caminhos sem lutar e não brigar pela vida. Para quem entende que a paz e perdão não tem nada de silencioso quando já se viveu algumas guerras. E por quem vive como se sentisse o seu desaparecimento a cada dia, pois as flores não perdem a sua cor, apenas vivem o suficiente para não desbotar. iv AGRADECIMENTOS Não agradecerei neste trabalho a nomes específicos que me atravessaram na minha caminhada enquanto o escrevia, mas sim as experiências que passei a viver nesse período de tempo em que pela primeira vez me permite viver sem ser apenas agredida. Pelos dias que passei a cuidar de mim mesma. Pela minha caminhada em análise que me permitiu entender subjetivamente o que eu buscava quando coloquei essa temática como pesquisa a ser realizada. -

Redalyc.Sérgio Milliet: Críticas a Anita Malfatti

Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros ISSN: 0020-3874 [email protected] Universidade de São Paulo Brasil Gomes Cardoso, Renata Sérgio Milliet: Críticas a Anita Malfatti Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, núm. 63, abril, 2016, pp. 219-234 Universidade de São Paulo São Paulo, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=405645350012 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto Sérgio Milliet: Críticas a Anita Malfatti [ Sérgio Milliet: art criticism on Anita Malfatti Renata Gomes Cardoso¹ RESUMO • A pintura de Anita Malfatti foi co- Brasil. • PALAVRAS-CHAVE • Crítica de mentada por diversos escritores, destacando-se Arte; Sérgio Milliet; Anita Malfatti; Arte Mo- entre eles Mário de Andrade, amigo que sempre derna; Modernismo; Escola de Paris. • ABS- a defendeu no âmbito do modernismo no Bra- TRACT • Many authors have discussed Anita sil, em críticas publicadas ou em cartas. Além Malfatti’s paintings, notably Mário de Andra- de Mário de Andrade e de Oswald de Andrade, de, her close friend and art critic, who wrote outro escritor que avaliou a produção da artis- about her relevance for the Brazilian Modern ta foi Sérgio Milliet, figura muito significativa Art, through articles and letters. Besides Má- naquele contexto, tanto por ter contribuído rio de Andrade and Oswald de Andrade, ano- com artigos para diversos jornais e revistas, ther important author of this period was Sér- quanto por ter viabilizado o contato dos artis- gio Milliet, who promoted the small group of tas e escritores brasileiros com personalidades Brazilian artists and writers in the Parisian relevantes do ambiente cultural francês. -

Modernism and the Search for Roots

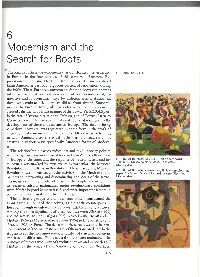

6 Modernism and the Search for Roots THE RADICAL artistic developments that transformed the visual arts 6. 1 Detail of Pl. 6.37. in Europe in the first decades of this century -Fauvism , Ex- pressionism , Cubism, D ada, Purism, Constructivism - entered Latin Ameri ca as part of a 'vigorous current of renovation' during the 1920s. These European movem ents did not, however, enter as intact or discrete styles, but were often adapted in individual, in novative and idiosyncratic ways by different artists. Almost all those who embraced M odernism did so from abroad. Some re mained in Europe; some, like Barradas with his 'vibrationism', created a distinct modernist m anner of their own [Pls 6.2,3,4,5] , or, in the case of Rivera in relation to Cubism , and of Torres-Garcfa to Constructivism, themselves contributed at crucial moments to the development of these m ovem ents in Europe. The fac t of being American, however, was registered in some form in the work of even the most convinced internationalists. Other artists returning to Latin Ameri ca after a relatively brief period abroad set about crea ting in various ways specifically America n forms of Modern ism . The relationship between radical art and revolut ionary politics was perhaps an even more crucial iss ue in Latin America than it was in Europe at the time; and the response of w riters, artists and in 6. 2 Rafa el Barradas, Study, 1911 , oil on cardboard, 46 x54 cm. , Museo Nacional de Arres Plasti cas, tellectuals was marked by two events in particular: the Mexican Montevideo. -

Chapter.11.Brazilian Cdr.Cdr

BRAZIL Chapter 11 Art, Literature and Poetry Brazil was colonized by Portugal in the middle of the 16th century. In those early times, owing to the primitive state of Portuguese civilization there, not much could be done in regard to art expression. The original inhabitants of the land, pre-Columbian Indigenous peoples, most likely produced various forms of art, but very little is known about this. Little remains, except from elaborate feather items used as body adornments by all different tribes and specific cultures like the Marajoara, who left sophisticated painted pottery. So, Brazilian art - in the Western sense of art - began in the late 16th century and, for the greater part of its evolution until early 20th century, depended wholly on European standards. 170 BRAZIL Pre-Columbian traditions Main article: Indigenous peoples in Brazil Santarém culture. Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi Bororo Indian with feather headdress and body painting 171 BRAZIL The oldest known art in Brazil is the cave paintings in Serra da Capivara National Park in the state of Piauí, dating back to c. 13,000 BC. More recent examples have been found in Minas Gerais and Goiás, showing geometric patterns and animal forms. One of the most sophisticated kinds of Pre- Columbian artifact found in Brazil is the sophisticated Marajoara pottery (c. 800–1400 AD), from cultures flourishing on Marajó Island and around the region of Santarém, decorated with painting and complex human and animal reliefs. Statuettes and cult objects, such as the small carved-stone amulets called muiraquitãs, also belong to these cultures. The Mina and Periperi cultures, from Maranhão and Bahia, produced interesting though simpler pottery and statuettes. -

ART DECO and BRAZILIAN MODERNISM a Dissertation

SLEEK WORDS: ART DECO AND BRAZILIAN MODERNISM A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Spanish By Patricia A. Soler, M.S. Washington, DC January 23, 2014 Copyright by Patricia A. Soler All rights reserved ii SLEEK WORDS: ART DECO AND BRAZILIAN MODERNISM Patricia A. Soler, M.S. Thesis advisor: Gwen Kirkpatrick, Ph.D. ABSTRACT I explore Art Deco in the Brazilian Modernist movement during the 1920s. Art Deco is a decorative arts style that rose to global prominence during this decade and its proponents adopted and adapted the style in order to nationalize it; in the case of Brazil, the style became nationalized primarily by means of the application of indigenous motifs. The Brazilian Modernists created their own manifestations of the style, particularly in illustration and graphic design. I make this analysis by utilizing primary source materials to demonstrate the style’s prominence in Brazilian Modernism and by exploring the handcrafted and mechanical techniques used to produce the movement’s printed texts. I explore the origins of the Art Deco style and the decorative arts field and determine the sources for the style, specifically avant-garde, primitivist, and erotic sources, to demonstrate the style’s elasticity. Its elasticity allowed it to be nationalized on a global scale during the 1920s; by the 1930s, however, many fascist-leaning forces co- opted the style for their own projects. I examine the architectural field in the Brazil during the 1920s. -

Bridging the Atlantic and Other Gaps: Artistic Connections Between Brazil and Africa – and Beyond Roberto Conduru

BRIDGING THE ATLANTIC AND OTHER GAPS: ARTISTIC CONNECTIONS BETWEEN BRAZIL AND AFRICA – AND BEYOND ROBERTO CONDURU London Snow Africa, London Hole Brazil 1998–99 consists of a pair of images captured by Milton Machado on the streets of London: a snow-covered map of Africa and a hole in the asphalt resembling the map of Brazil. Beyond questioning the political dimensions of cartography, the work provides an interesting means of access to connections between the visual arts and the question of Afro-Brazilian socio-cultural influences.1 Its apparently literal title possesses a sonority that resonates with other meanings: difference, identification, domination. It leads us to consider how relations between Brazil and Africa are often forged by external mediators, artists not necessarily of African descent, establishing diffuse networks of meaning in the Atlantic and configuring unique images of Africa in Brazil. It also allows us to understand how, regardless of the fact that it is a constant in the process of Brazilian artistic modernisation, Afro-Brazilian hybridity is infrequently perceived and analysed, an absence that correlates with Brazilian society’s more general silence regarding African descent. AFROMODERNITY IN BRAZIL Afro-Brazilian influences are both inherent in and essential to the understanding of Brazilian culture. However, these connections take place in different modes and with varying degrees of intensity over time and space, certain moments and places being of particular interest to the process of artistic modernisation. One such conjunction took place between the late 1800s and the early twentieth century in the academic milieu of Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo and Bahia, within the context of the intensification of the abolitionist process, the end of slavery and the beginning of the Republican regime. -

Anita Malfatti Suscitou Enorme Polêmica Ao Expor Suas Tintas Expressionistas No Brasil Do Começo Do Século XX

31 de julho a 26 de setembro de 2010 Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil – Rio de Janeiro Pioneira da pintura moderna, Anita Malfatti suscitou enorme polêmica ao expor suas tintas expressionistas no Brasil do começo do século XX. As duras críticas que recebeu, principalmente do célebre escritor – então jornalista – Monteiro Lobato, a transformaram em uma espécie de ícone de uma nova era. Prontamente defendida e adotada por aqueles que seriam os pi- lares da construção de uma visão modernizadora de nossa cultura, os futuros modernistas Mário e Oswald de Andrade, Tarsila do Amaral e Menotti Del Picchia, Anita tinha a ousadia de fugir das amarras so- ciais que cerceavam a mulher da época e se colocar na posição de vanguarda ao retratar – de maneira distante do academicismo em voga – personagens marginalizados dos centros urbanos. Com a exposição Anita Malfatti – 120 anos de nascimento, o Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil reafirma seu compromisso com a de- mocratização e acesso à cultura, oferecendo a seu público a oportu- nidade de admirar a obra desta que é considerada uma das maiores pintoras brasileiras. Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil As a pioneer in modern painting, Anita Malfatti caused great polemic with her expressionist paintings in Brazil in early 20th century. She was hardly criticized, particularly by noted writer Monteiro Lobato, still a jour- nalist then, and such critics changed her into an icon of the new era. Promptly defended and adopted by those who would be the pil- lars of a renovating view of our culture, future modernists Mário de Andrade, Oswald de Andrade, Tarsila do Amaral and Menotti Del Picchia, Anita dared to question the strict social models imposed to women and assume the challenging position of vanguard when she showed – not using the academicism then in vogue – marginalized characters of urban centers. -

As Exposições De Segall, Malfatti E Goeldi No Início Do Modernismo Brasileiro

17° Encontro Nacional da Associação Nacional de Pesquisadores em Artes Plásticas Panorama da Pesquisa em Artes Visuais – 19 a 23 de agosto de 2008 – Florianópolis Um outro moderno? As exposições de Segall, Malfatti e Goeldi no início do modernismo brasileiro Profa. Dra. Vera Beatriz Siqueira (UERJ) Resumo: Desde 2002 venho desenvolvendo o projeto “Estilo e instituição”, no qual analisei as estratégias e os efeitos da institucionalização da arte moderna e contemporânea no Brasil, a partir do estudo de artistas significativos para a modernidade estética no país. A partir de 2008, a idéia central do projeto é pensar no significado de certos eventos artísticos e culturais, bastante variados no tempo, de forma a, a partir desses estudos parciais, entre dúvidas e lacunas, ir formando uma história não linear, sem teleologia ou finalismo. Entre os fatos que elegi, e que gostaria de apresentar nesta comunicação, encontra- se a trinca de exposições de Lasar Segall em 1913, Anita Malfatti em 1917 e Goeldi em 1921, todos artistas de formação expressionista, com repercussões críticas polêmicas ou negativas no quadro do incipiente modernismo brasileiro. Analisar a significação histórica e cultural deste fato é objetivo central de minha pesquisa. Palavras-chave: Exposições de arte; expressionismo no Brasil; arte moderna brasileira Since 2002 is being developed the project "Style and institution", in which I analyzed the strategies and the effects of the institutionalization of the modern art and contemporary in Brazil, studying the cases of significant artists for the modernity esthetics in the country. From 2008, the central idea of the project is to think of the meaning of certain cultural and artistic events varied in the time, from which partial studies, between doubts and gaps, is intended to be formed a new history, without teleology or finalism. -

Sticas No Paãłs" and the Silence of Brazilian Art C

Artl@s Bulletin Volume 8 Issue 1 Women Artists Shows.Salons.Societies Article 14 (1870s-1970s) 2019 The exhibition “Contribuição da mulher às artes plásticas no país" and the silence of Brazilian art criticism Marina Mazze Cerchiaro University of São Paulo, [email protected] ana paula simioni Universidade de São Paulo, [email protected] Talita Trizoli Ms Universidade de Sao Paulo, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/artlas Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Cerchiaro, Marina Mazze; ana paula simioni; and Talita Trizoli Ms. "The exhibition “Contribuição da mulher às artes plásticas no país" and the silence of Brazilian art criticism." Artl@s Bulletin 8, no. 1 (2019): Article 14. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. This is an Open Access journal. This means that it uses a funding model that does not charge readers or their institutions for access. Readers may freely read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of articles. This journal is covered under the CC BY-NC-ND license. W.A.S. (1870s-1970s) The exhibition Contribuição da mulher às artes plásticas no país and the silence of Brazilian art criticism Marina Mazze Cerchiaro Ana Paula Cavalcanti Simioni Talita Trizoli University of São Paulo Abstract In 1960 the São Paulo Museum of Modern Art inaugurated the exhibition Contribuição da mulher às artes plásticas no país. This was the first female collective exhibition of a large scale to happen in Brazil. -

Tarsila Do Amaral

ÁREA DE EDUCACIÓN Y ACCIÓN CULTURAL | PROPUESTAS PARA EDUCADORES Tarsila do Amaral Do Amaral, Tarsila Abaporu, 1928 Óleo sobre tela 85 x 73 cm Malba - Fundación Costantini ¡Mirá! La pintura que vemos se titula Abaporu y fue hecha por Tarsila do Amaral en 1928. La técnica utilizada es óleo sobre tela y sus medidas son 85 cm de alto por 73 cm de ancho. En la ima- gen podemos ver una figura muy grande y de perfil, sentada en una planicie verde, con un pie y una mano desproporcio- nados que se apoyan en el sue- lo. Este personaje está doblado sobre sí mismo y ocupa casi la totalidad del cuadro. Su minús- cula cabecita es sostenida por el otro brazo, también pequeño –¿o es su gran nariz?–, que reposa en la enorme rodilla. Acompañan a esta figura un cactus con una flor que explota o un sol como un cítrico. Las formas fueron bien definidas y los colores predominantes, verde, azul y amarillo, son los mismos que los de la bandera del Brasil. 1900 1910 1907 Picasso pinta Señoritas de Aviñón. 1913 Lasar Segall expone obras expresionistas en San Pablo. 1917 Anita Malfatti exhibe obras fauves en San Pablo. 1914-1918 Primera Guerra Mundial. BIOGRAFÍA TARSILA DO AMARAL EN CONTEXTO Tarsila do Amaral El movimiento modernista, en el Brasil, surge en San Pablo 1886 | 1973 en la década del 20. Esta ciudad se estaba transformando gracias a un proceso creciente de industrialización, a la vez que los inmigrantes que estaban llegando traían nuevos há- bitos y formas de vida. -

OS DELÍRIOS DE PAGU1* Simone Accorsi**

OS DELÍRIOS DE PAGU1* Simone Accorsi** Resumen El presente artículo es un avance de investigación del proyecto “El Poder de la Pluma en la Creación de la Identidad Nacional” que trata de la vida y obra de la escritora, poeta, periodista y activista política Patrícia Redher Galvão, más conocida como Pagu. Considerada la “musa” del Movimiento Antropofágico que sentó las bases del Modernismo en Brasil, esa mujer luchó por sus ideales con bravura y determinación en la época de la terrible dictadura de Getúlio Vargas. Palabras Clave: Pagu, Patrícia Rehder Galvão, género, activismo político en Brasil. Resumo O presente artigo é um avanço de pesquisa do projeto “O Poder da Pluma na Criação da Identidade Nacional” que analisa a vida e a obra da escritora, poeta, jornalista e ativista política Patrícia Redher Galvão, mais conhecida como Pagu. Considerada a “musa” do Movimento Antropofágico que estabeleceu as bases do Modernismo no Brasil, essa mulher lutou por seus ideais com bravura e determinação durante a época da terrível ditadura de Getúlio Vargas. Palavras chave: Pagu, Patricia Rehder Galvão, gênero, ativismo político no Brasil. Abstract This article focuses on the life and work of Patrícia Rehder Galvão (Pagu) one of the most important names of Modernism in Brazil. Journalist, poet, writer and political activist, member of the Communist Party, Patrícia Rehder Galvão was an example of determination in the struggle for the civilian rights during the terrible * Artículo tipo 2: de reflexión según clasificación de Colciencias: Este trabalho apresenta os primeiros resultados do projeto de pesquisa “El Poder de la Pluma en la Creación de la Identidad Nacional “ (CI 4314) para o Grupo de Investigación en Género, Literatura y Discurso, da Faculdade de Humanidades, Universidad del Valle, Cali, Colômbia.