The First Major U.S. Museum Exhibition of Tarsila Do Amaral Celebrates the Artist's Pioneering Work and Lasting Influence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feb. 7 to Apr. 30, 2017 Great Hall

Ministry of Culture and Museu de Arte To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Moderna de São Paulo present exhibition that inaugurated Brazilian modernism, Anita Malfatti: 100 Years of Modern Art gathers at FEB. 7 MAM’s Great Hall about seventy different works covering the path of one of the main names in TO Brazilian art in the 20th century. Anita Malfatti’s exhibition in 1917 was crucial to the emergence of the group who would champion modern art in Brazil, so much so that APR. 30, critic Paulo Mendes de Almeida considered her as the “most historically critical character in the 2017 1922 movement.” Regina Teixeira de Barros’ curatorial work reveals an artist who is sensitive to trends and discussions in the first half of the 20th century, mindful of her status and her choices. This exhibition at MAM recovers drawings and paintings by Malfatti, divided into three moments in her path: her initial years that consecrated her as “trigger of Brazilian modernism”; the time she spent training in Paris and her naturalist production; and, finally, her paintings with folk themes. With essays by Regina Teixeira de Barros and GREAT Ana Paula Simioni, this edition of Moderno MAM Extra is an invitation for the public to get to know HALL this great artist’s choices. Have a good read! MASTER SPONSORSHIP SPONSORSHIP CURATED BY REALIZATION REGINA TEIXEIRA DE BARROS One hundred years have gone by since the 3 03 ANITA Exposição de pintura moderna Anita Malfatti [Anita Malfatti Modern Painting Exhibition] would forever CON- MALFATTI, change the path of art history in Brazil. -

Group Exhibition at Pina Estação Brings Together Works Which Allude to Fictions About the Origin of the World

Group exhibition at Pina Estação brings together works which allude to fictions about the origin of the world Experimental works by Antonio Dias, Carmela Gross, Lothar Baumgarten, Solange Pessoa and Tunga suggest cosmogonic narratives Opening: November 10th, 2018, Saturday, at 11 am Visitation: until February 11th, 2019 Pinacoteca de São Paulo, museum of the São Paulo State Secretariat of Culture, presents, from November 10th, 2018 to February 11th, 2019, the exhibition Invention of Origin, on the fourth floor of Pina Estação. With curatorship by Pinacoteca's Nucleus of Research and Criticism and under general coordination of José Augusto Ribeiro, the museum curator, the group exhibition takes as the starting point the film The Origin of the Night: Amazon Cosmos (1973-77), by the German artist Lothar Baumgarten. The film, rarely exhibited, will be presented alongside a selection of works by four Brazilian artists — Antonio Dias, Carmela Gross, Solange Pessoa and Tunga. In common, the selected works allude to primordial times and actions which could have contributed to the narratives about the origin of life. Shot on 16 mm between 1973 and 1977, The Origin of the Night: Amazon Cosmos, by Lothar Baumgarten, is based on a Tupi myth, registered by the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, on the origin of the night — which, according to the narrative, used to “sleep” under waters, when animals still did not exist and things had the power of speech. From images captured in the Reno River, between Dusseldorf and Cologne, the artist creates ambiguous situations. “The images are paradoxical, they show a kind of virgin forest in which, however, the waste of human civilization is spread. -

Hans Ulrich Obrist a Brief History of Curating

Hans Ulrich Obrist A Brief History of Curating JRP | RINGIER & LES PRESSES DU REEL 2 To the memory of Anne d’Harnoncourt, Walter Hopps, Pontus Hultén, Jean Leering, Franz Meyer, and Harald Szeemann 3 Christophe Cherix When Hans Ulrich Obrist asked the former director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Anne d’Harnoncourt, what advice she would give to a young curator entering the world of today’s more popular but less experimental museums, in her response she recalled with admiration Gilbert & George’s famous ode to art: “I think my advice would probably not change very much; it is to look and look and look, and then to look again, because nothing replaces looking … I am not being in Duchamp’s words ‘only retinal,’ I don’t mean that. I mean to be with art—I always thought that was a wonderful phrase of Gilbert & George’s, ‘to be with art is all we ask.’” How can one be fully with art? In other words, can art be experienced directly in a society that has produced so much discourse and built so many structures to guide the spectator? Gilbert & George’s answer is to consider art as a deity: “Oh Art where did you come from, who mothered such a strange being. For what kind of people are you: are you for the feeble-of-mind, are you for the poor-at-heart, art for those with no soul. Are you a branch of nature’s fantastic network or are you an invention of some ambitious man? Do you come from a long line of arts? For every artist is born in the usual way and we have never seen a young artist. -

Spring 2012 Course Guide TABLE of CONTENTS

WOMEN, GENDER, SEXUALITY STUDIES PROGRAM UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST Spring 2012 Course Guide TABLE OF CONTENTS This catalog contains descriptions of all Women’s Studies courses for which information was available in our office by the publication deadline for pre-registration. Please note that some changes may have been made in time, and/or syllabus since our print deadline. Exact information on all courses may be obtained by calling the appropriate department or college. Please contact the Five-College Exchange Office (545-5352) for registration for the other schools listed. Listings are arranged in the following order: Options in Women's Studies .................................................................................................................. 1-3 Undergraduate and Graduate Programs explained in detail. Faculty in Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies .................................................................................. 4-5 Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies Core Courses ............................................................................ 6-9 Courses offered through the Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies program Women of Color Courses .................................................................................................................. 10-15 Courses that count towards the Woman of Color requirement for UMass Amherst Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies undergraduate majors and minors. Departmental Courses ..................................................................................................................... -

Pagu: a Arte No Feminino Como Performance De Si

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS MESTRADO INTERDISCIPLINAR EM PERFORMANCES CULTURAIS LUCIENNE DE ALMEIDA MACHADO PAGU: A ARTE NO FEMININO COMO PERFORMANCE DE SI GOIÂNIA, MARÇO DE 2018. UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS MESTRADO INTERDISCIPLINAR EM PERFORMANCES CULTURAIS LUCIENNE DE ALMEIDA MACHADO PAGU: A ARTE NO FEMININO COMO PERFORMANCE DE SI Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação Interdisciplinar em Performances Culturais, para obtenção do título de Mestra em Performances Culturais pela Universidade Federal de Goiás. Orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Sainy Coelho Borges Veloso. Co-orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Marcela Toledo França de Almeida. GOIÂNIA, MARÇO DE 2018. i ii iii Dedico este trabalho a quem sabe que a pele é fina diante da abertura do peito, que o coração a toca. Por quem sabe que é impossível viver por certos caminhos sem lutar e não brigar pela vida. Para quem entende que a paz e perdão não tem nada de silencioso quando já se viveu algumas guerras. E por quem vive como se sentisse o seu desaparecimento a cada dia, pois as flores não perdem a sua cor, apenas vivem o suficiente para não desbotar. iv AGRADECIMENTOS Não agradecerei neste trabalho a nomes específicos que me atravessaram na minha caminhada enquanto o escrevia, mas sim as experiências que passei a viver nesse período de tempo em que pela primeira vez me permite viver sem ser apenas agredida. Pelos dias que passei a cuidar de mim mesma. Pela minha caminhada em análise que me permitiu entender subjetivamente o que eu buscava quando coloquei essa temática como pesquisa a ser realizada. -

Redalyc.Sérgio Milliet: Críticas a Anita Malfatti

Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros ISSN: 0020-3874 [email protected] Universidade de São Paulo Brasil Gomes Cardoso, Renata Sérgio Milliet: Críticas a Anita Malfatti Revista do Instituto de Estudos Brasileiros, núm. 63, abril, 2016, pp. 219-234 Universidade de São Paulo São Paulo, Brasil Disponível em: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=405645350012 Como citar este artigo Número completo Sistema de Informação Científica Mais artigos Rede de Revistas Científicas da América Latina, Caribe , Espanha e Portugal Home da revista no Redalyc Projeto acadêmico sem fins lucrativos desenvolvido no âmbito da iniciativa Acesso Aberto Sérgio Milliet: Críticas a Anita Malfatti [ Sérgio Milliet: art criticism on Anita Malfatti Renata Gomes Cardoso¹ RESUMO • A pintura de Anita Malfatti foi co- Brasil. • PALAVRAS-CHAVE • Crítica de mentada por diversos escritores, destacando-se Arte; Sérgio Milliet; Anita Malfatti; Arte Mo- entre eles Mário de Andrade, amigo que sempre derna; Modernismo; Escola de Paris. • ABS- a defendeu no âmbito do modernismo no Bra- TRACT • Many authors have discussed Anita sil, em críticas publicadas ou em cartas. Além Malfatti’s paintings, notably Mário de Andra- de Mário de Andrade e de Oswald de Andrade, de, her close friend and art critic, who wrote outro escritor que avaliou a produção da artis- about her relevance for the Brazilian Modern ta foi Sérgio Milliet, figura muito significativa Art, through articles and letters. Besides Má- naquele contexto, tanto por ter contribuído rio de Andrade and Oswald de Andrade, ano- com artigos para diversos jornais e revistas, ther important author of this period was Sér- quanto por ter viabilizado o contato dos artis- gio Milliet, who promoted the small group of tas e escritores brasileiros com personalidades Brazilian artists and writers in the Parisian relevantes do ambiente cultural francês. -

Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Newsletter, Number 55, Fall 2020

Number 55 – Fall 2020 NEWSLETTERAlumni PatriciaEichtnbaumKaretzky andZhangEr Neoclasicos rnE'-RTISTREINVENTiD,1~1-1= THEME""'lLC.IIEllMNICOLUCTION MoMA Ano M. Franco .. ..H .. •... 1 .1 e-i =~-:.~ CALLi RESPONSE Nyu THE INSTITUTE Published by the Alumni Association of II IOF FINE ARTS 1 Contents Letter from the Director In Memoriam ................. .10 The Year in Pictures: New Challenges, Renewed Commitments, Alumni at the Institute ..........16 and the Spirit of Community ........ .3 Iris Love, Trailblazing Archaeologist 10 Faculty Updates ...............17 Conversations with Alumni ....... .4 Leatrice Mendelsohn, Alumni Updates ...............22 The Best Way to Get Things Done: Expert on Italian Renaissance An Interview with Suzanne Deal Booth 4 Art Theory 11 Doctors of Philosophy Conferred in 2019-2020 .................34 The IFA as a Launching Pad for Seventy Nadia Tscherny, Years of Art-Historical Discovery: Expert in British Art 11 Master of Arts and An Interview with Jack Wasserman 6 Master of Science Dual-Degrees Dora Wiebenson, Conferred in 2019-2020 .........34 Zainab Bahrani Elected to the American Innovative, Infuential, and Academy of Arts and Sciences .... .8 Prolifc Architectural Historian 14 Masters Degrees Conferred in 2019-2020 .................34 Carolyn C Wilson Newmark, Noted Scholar of Venetian Art 15 Donors to the Institute, 2019-2020 .36 Institute of Fine Arts Alumni Association Offcers: Alumni Board Members: Walter S. Cook Lecture Susan Galassi, Co-Chair President Martha Dunkelman [email protected] and William Ambler [email protected] Katherine A. Schwab, Co-Chair [email protected] Matthew Israel [email protected] [email protected] Yvonne Elet Vice President Gabriella Perez Derek Moore Kathryn Calley Galitz [email protected] Debra Pincus [email protected] Debra Pincus Gertje Utley Treasurer [email protected] Newsletter Lisa Schermerhorn Rebecca Rushfeld Reva Wolf, Editor Lisa.Schermerhorn@ [email protected] [email protected] kressfoundation.org Katherine A. -

Eugenia Scarzanella / Mônica Raisa Schpun (Eds.) Sin Fronteras: Encuentros De Mujeres Y Hombres Entre América Latina Y Europa (Siglos XIX-XX)

Eugenia Scarzanella / Mônica Raisa Schpun (eds.) Sin fronteras: encuentros de mujeres y hombres entre América Latina y Europa (siglos XIX-XX) B I B L I O T H E C A I B E R O - A M E R I C A N A Publicaciones del Instituto Ibero-Americano Fundación Patrimonio Cultural Prusiano Vol. 123 B I B L I O T H E C A I B E R O - A M E R I C A N A Eugenia Scarzanella / Mônica Raisa Schpun (eds.) Sin fronteras: encuentros de mujeres y hombres entre América Latina y Europa (siglos XIX-XX) Iberoamericana · Vervuert 2008 Bibliografic information published by Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliografic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.ddb.de © Iberoamericana 2008 Amor de Dios, 1 E-28014 Madrid [email protected] www.ibero-americana.net © Vervuert Verlag 2008 Elisabethenstr. 3-9 D-60594 Frankfurt am Main [email protected] www.ibero-americana.net ISBN 978-84-8489-XXX-X ISBN 978-3-86527-429-8 Diseño de la cubierta: Michael Ackermann Ilustración de la cubierta: © Composición: Anneliese Seibt, Instituto Ibero-Americano, Berlín Este libro está impreso íntegramente en papel ecológico blanqueado sin cloro Impreso en España Índice Eugenia Scarzanella y Mônica Raisa Schpun Introdução ........................................................................................... 7 Katrin Hoffmann Género y diferencia cultural: las coordenadas de una amistad epistolar entre Mary Mann y Domingo F. Sarmiento .......................................................................................... 17 Sandra Carreras “Spengler, Quesada y yo...”. Intercambio intelectual y relaciones personales entre la Argentina y Alemania ....................... 43 Carmen Ramos Escandón Genaro García: la influencia del feminismo europeo en sus posiciones sobre las relaciones entre hombres y mujeres en el matrimonio ............................................................... -

Fire, Corruption and the Political Neglect Destroying Part of Brazilian Art and History

December 2018 West East Journal of Social Sciences- Volume 7 Number 3 FIRE, CORRUPTION AND THE POLITICAL NEGLECT DESTROYING PART OF BRAZILIAN ART AND HISTORY: THE GENERAL SITUATION AND THE SPECIFIC CASE OF RODOLPHO AMOÊDO’S DECORATIVE PAINTING Leandro Brito de Mattos Instituto Federal de Roraima (Federal Institute of Roraima), Brazil Abstract At the beginning of XX century some Brazilian cities tried to renovate their architecture by emulating a Parisian atmosphere and that included the painting decoration for public buildings. Rodolpho Amoêdo was one of the famous Brazilian artists of that time commissioned to decorate several public buildings. However now, around 100 years later, the institutions that houses these paintings have a lack of information about them and some of these paintings are suffering because of bad preservation. This situation might be explaining in part by the political and economic crises Brazil have been facing since 2015. This paper will highlight this connection. Keywords: Brazilian art, Rodolpho Amoêdo, Art history, Decorative painting. 1. Introduction: This is a study about the actual situation of the decorative work the Brazilian painter Rodolpho Amoêdo has done for some public buildings on several Brazilian states. Analyzing the conservation state of these paintings, historical documents about them and the posture of the institutions where we find them we can realize a connection with Brazilian politics: Some paintings need restoration and some need more studies about them; Brazil faces a several political crises with strong economic effects and the authorities doesn’t act as if culture is a relevant matter. The government funding for culture has been reduced to something close to zero and some catastrophic events are happening. -

Modernism and the Search for Roots

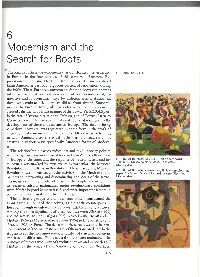

6 Modernism and the Search for Roots THE RADICAL artistic developments that transformed the visual arts 6. 1 Detail of Pl. 6.37. in Europe in the first decades of this century -Fauvism , Ex- pressionism , Cubism, D ada, Purism, Constructivism - entered Latin Ameri ca as part of a 'vigorous current of renovation' during the 1920s. These European movem ents did not, however, enter as intact or discrete styles, but were often adapted in individual, in novative and idiosyncratic ways by different artists. Almost all those who embraced M odernism did so from abroad. Some re mained in Europe; some, like Barradas with his 'vibrationism', created a distinct modernist m anner of their own [Pls 6.2,3,4,5] , or, in the case of Rivera in relation to Cubism , and of Torres-Garcfa to Constructivism, themselves contributed at crucial moments to the development of these m ovem ents in Europe. The fac t of being American, however, was registered in some form in the work of even the most convinced internationalists. Other artists returning to Latin Ameri ca after a relatively brief period abroad set about crea ting in various ways specifically America n forms of Modern ism . The relationship between radical art and revolut ionary politics was perhaps an even more crucial iss ue in Latin America than it was in Europe at the time; and the response of w riters, artists and in 6. 2 Rafa el Barradas, Study, 1911 , oil on cardboard, 46 x54 cm. , Museo Nacional de Arres Plasti cas, tellectuals was marked by two events in particular: the Mexican Montevideo. -

Afro-Brazilian Religious Suppression in 1920S and 1930S Rio De Janeiro Brittney Teal-Cribbs Western Oregon University, [email protected]

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History Fall 2012 Afro-Brazilian Religious Suppression in 1920s and 1930s Rio de Janeiro Brittney Teal-Cribbs Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the History Commons, and the Latin American Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Teal-Cribbs, Brittney L. "Afro-Brazilian Religious Suppression in 1920s and 1930s Rio de Janeiro." Department of History Capstone paper, Western Oregon University, 2012. This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Afro-Brazilian Religious Suppression in 1920s and 1930s Rio de Janeiro Britney Teal-Cribbs HST 600 Brazil and Chile Seminar Professor John Rector December 12, 2012 2 INTRODUCTION Pinning down the history of any religion proves, at the best of times, elusive. In the case of Afro-Brazilian religions, it becomes nearly impossible. Not only have African religious customs blended with those of European and Indigenous religions over time, but those new, syncretic forms have themselves snaked around, emphasizing varying components, adding new ones, and shifting away from others. It is into these turbulent waters that this paper wades, by first looking at the history of scholarship surrounding Afro-Brazilian religions, and then turning to look at some of the social forces and challenges that Afro-Brazilian religions faced in Rio de Janeiro from the mid-1920s through the 1930s and the dictatorship of Getúlio Vargas, which emerged in 1930 and influenced all aspects of Brazilian life. -

New York University Bulletin 2018–2020 New York University Bulletin 2018–2020

New York University Bulletin 2018–2020 New York University Bulletin 2018–2020 College of Arts and Science Announcement for the 186th and 187th Sessions New York University Washington Square New York, New York 10003 Notice: The online version of the CAS Bulletin (at bulletin.cas.nyu.edu) contains revisions and updates in courses, programs, requirements, and staffing that occurred after the publication of the PDF and print version. The online Bulletin is subject to change and will be revised and updated as necessary. Students who require a printed copy of any portion of the updated online Bulletin but do not have Internet access should see a College of Arts and Science adviser or administrator for assistance. The policies, requirements, course offerings, schedules, activities, tuition, fees, and calendar of the school and its departments and programs set forth in this bulletin are subject to change without notice at any time at the sole discretion of the administration. Such changes may be of any nature, including, but not limited to, the elimination of the school or college, programs, classes, or activities; the relocation of or modification of the content of any of the foregoing; and the cancellation of scheduled classes or other academic activities. Payment of tuition or attendance at any classes shall constitute a student’s acceptance of the administration’s rights as set forth in the above paragraph. Contents An Introduction to New York University . 5 English, Department of..............178 Philosophy, Department of . 362 The Schools, Colleges, Institutes, and Environmental Studies, Physics, Department of . .370 Programs of the University ..............6 Department of .