Chapter.11.Brazilian Cdr.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feb. 7 to Apr. 30, 2017 Great Hall

Ministry of Culture and Museu de Arte To celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Moderna de São Paulo present exhibition that inaugurated Brazilian modernism, Anita Malfatti: 100 Years of Modern Art gathers at FEB. 7 MAM’s Great Hall about seventy different works covering the path of one of the main names in TO Brazilian art in the 20th century. Anita Malfatti’s exhibition in 1917 was crucial to the emergence of the group who would champion modern art in Brazil, so much so that APR. 30, critic Paulo Mendes de Almeida considered her as the “most historically critical character in the 2017 1922 movement.” Regina Teixeira de Barros’ curatorial work reveals an artist who is sensitive to trends and discussions in the first half of the 20th century, mindful of her status and her choices. This exhibition at MAM recovers drawings and paintings by Malfatti, divided into three moments in her path: her initial years that consecrated her as “trigger of Brazilian modernism”; the time she spent training in Paris and her naturalist production; and, finally, her paintings with folk themes. With essays by Regina Teixeira de Barros and GREAT Ana Paula Simioni, this edition of Moderno MAM Extra is an invitation for the public to get to know HALL this great artist’s choices. Have a good read! MASTER SPONSORSHIP SPONSORSHIP CURATED BY REALIZATION REGINA TEIXEIRA DE BARROS One hundred years have gone by since the 3 03 ANITA Exposição de pintura moderna Anita Malfatti [Anita Malfatti Modern Painting Exhibition] would forever CON- MALFATTI, change the path of art history in Brazil. -

Brazil Information RESOURCE

Did You Know? Brazil is named after the Brazilwood tree. Photo courtesy of mauroguanandi (@flickr.com) - granted under creative commons licence attribution Where Is Brazil? Brazil is the largest country in South America and the fifth largest country in the world! It has a long coastal border with the Atlantic Ocean and borders with ten different countries. Using an atlas, can you find the names of all the countries Brazil shares a border with? Fast Facts About Brazil Population: Capital city: Largest city: 196.6 million Brasilia São Paulo Currency: Main religion: Official language: Real Catholicism Portuguese* *although there are about 180 indigenous languages! Brazilian Flag In the middle of the flag is Can you find out the meaning of the a blue globe with 27 stars. flag and the words in the middle? Photo courtesy of mauroguanandi (@flickr.com) - granted under creative commons licence attribution History of Brazil Brazil is the only Portuguese-speaking country in South America. In 1494, the treaty of Tordesillas divided the Americas between Spain and Portugal (Line of Demarcation). Portugal claimed possession of Brazil on 22nd April 1500, as Pedro Alvares Cabral, the Portuguese fleet commander, landed on the coast. Brazil gained its independence from Portugal in 1822. The culture of Brazil is still mainly influenced by the Portuguese. The Amazon River The Amazon is the largest river in the world and the Amazon rainforest is the largest tropical forest in the world. Photo courtesy of CIAT International Center for Tropical Agriculture (@flickr.com) - granted under creative commons licence attribution Amazon Rainforest The Amazon rainforest covers more than 50% of the country. -

Camila Dazzi1 - [email protected]

Anais II Encontro Nacional de Estudos da Imagem 12, 13 e 14 de maio de 2009 Londrina-PR IMAGENS DO EMININO NO COTIDIANO DA ANTIGA ROMA A PRODUÇÃO DOS ARTISTAS BRASILEIROS Camila Dazzi1 - [email protected] Resumo: Que relações nós poderíamos estabelecer entre o artistas brasileiros, como Henrique Bernardelli, Pedro Weingärtner, Zeferino da Costa e Lawrwnce Alma-Tadema, um dos mais celebrados pintores do século XIX? Para respondermos a essa e a outras perguntas precisamos compreender o meio artístico no qual ambos estiveram imersos: a Itália de finais do oitocentos. O presente trabalho busca compreender a inserção dos artistas brasileiros em um significativo grupo de pintores, escultores e literatos, italianos e estrangeiros como Tedema, que, atuantes em Roma e Nápoles a partir de meados do século XIX, se voltaram para Pompéia, e mais amplamente para a antiga Roma, em busca de temas para as suas produções artísticas, conhecidas genericamente como neo-pompeianas. Palavras-chave: Pintura Neo-pompeiana, Relações artísticas Brasil-Itália, Pintura século XIX Abstract: What relations could be established between the Brazilian artists as Henrique Bernardelli, Pedro Weingärtner, Zeferino da Costa and Lawrence Alma-Tadema, one of the most celebrated painters of 19th century? To answer this and other questions we need to understand the artistic context in which both were immersed: the Italy of the end of the 800. The present paper tries to understand the insertion of this artists in a significant group of painters, sculptors and men of letters, Italians and foreigners as Alma-Tadema, that, operating in Rome and Naples in the middle of 19th century, turned their attentions to Pompeii and, more generically, to the old Rome, in search of subjects for their so-called neo-pompeian productions. -

Canções E Modinhas: a Lecture Recital of Brazilian Art Song Repertoire Marcía Porter, Soprano and Lynn Kompass, Piano

Canções e modinhas: A lecture recital of Brazilian art song repertoire Marcía Porter, soprano and Lynn Kompass, piano As the wealth of possibilities continues to expand for students to study the vocal music and cultures of other countries, it has become increasingly important for voice teachers and coaches to augment their knowledge of repertoire from these various other non-traditional classical music cultures. I first became interested in Brazilian art song repertoire while pursuing my doctorate at the University of Michigan. One of my degree recitals included Ernani Braga’s Cinco canções nordestinas do folclore brasileiro (Five songs of northeastern Brazilian folklore), a group of songs based on Afro-Brazilian folk melodies and themes. Since 2002, I have been studying and researching classical Brazilian song literature and have programmed the music of Brazilian composers on nearly every recital since my days at the University of Michigan; several recitals have been entirely of Brazilian music. My love for the music and culture resulted in my first trip to Brazil in 2003. I have traveled there since then, most recently as a Fulbright Scholar and Visiting Professor at the Universidade de São Paulo. There is an abundance of Brazilian art song repertoire generally unknown in the United States. The music reflects the influence of several cultures, among them African, European, and Amerindian. A recorded history of Brazil’s rich music tradition can be traced back to the sixteenth-century colonial period. However, prior to colonization, the Amerindians who populated Brazil had their own tradition, which included music used in rituals and in other aspects of life. -

Natália Cristina De Aquino Gomes

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SÃO PAULO ESCOLA DE FILOSOFIA, LETRAS E CIÊNCIAS HUMANAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM HISTÓRIA DA ARTE NATÁLIA CRISTINA DE AQUINO GOMES RETRATO DE ARTISTA NO ATELIÊ: a representação de pintores e escultores pelos pincéis de seus contemporâneos no Brasil (1878-1919) Guarulhos 2019 NATÁLIA CRISTINA DE AQUINO GOMES RETRATO DE ARTISTA NO ATELIÊ: a representação de pintores e escultores pelos pincéis de seus contemporâneos no Brasil (1878-1919) Dissertação de Mestrado apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Arte da Universidade Federal de São Paulo para obtenção do título de Mestre em História da Arte. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Elaine Cristina Dias. Guarulhos 2019 2 AQUINO GOMES, Natália Cristina de. Retrato de artista no ateliê: a representação de pintores e escultores pelos pincéis de seus contemporâneos no Brasil (1878-1919)/ Natália Cristina de Aquino Gomes. – Guarulhos, 2019. 250 f. Dissertação (mestrado em História da Arte) – Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Escola de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Arte, 2019. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Elaine Cristina Dias. Título em inglês: Portrait of artist in the studio: the representation of painters and sculptors by the brushes of their contemporaries in Brazil (1878-1919). 1. Retrato. 2. Ateliê. 3. Arte Brasileira. 4. Século XIX. 5. Início do século XX. I. Dias, Elaine Cristina. II. Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Escola de Filosofia, Letras e Ciências Humanas, Programa de Pós-Graduação em História da Arte. III. Título. 3 NATÁLIA CRISTINA DE AQUINO GOMES RETRATO DE ARTISTA NO ATELIÊ: a representação de pintores e escultores pelos pincéis de seus contemporâneos no Brasil (1878-1919) DISSERTAÇÃO apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em História da Arte da Universidade Federal de São Paulo para obtenção do título de MESTRE EM HISTÓRIA DA ARTE. -

Histories of Nineteenth-Century Brazilian

Perspective Actualité en histoire de l’art 2 | 2013 Le Brésil Histories of nineteenth-century Brazilian art: a critical review of bibliography, 2000-2012 Histoires de l’art brésilien du XIXe siècle : un bilan critique de la bibliographie, 2000-2012 Histórias da arte brasileira do século XIX: uma revisão critica da bibliografia Geschichten der brasilianischen Kunst des 19. Jahrhunderts : eine kritische Bilanz der Bibliographie, 2000-2012 Storie dell’arte brasiliana dell’Ottocento: un bilancio critico della bibliografia, 2000-2012 Historias del arte brasileño del siglo XIX: un balance crítico de la bibliografía, 2000-2012 Rafael Cardoso Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/3891 DOI: 10.4000/perspective.3891 ISSN: 2269-7721 Publisher Institut national d'histoire de l'art Printed version Date of publication: 31 December 2013 Number of pages: 308-324 ISSN: 1777-7852 Electronic reference Rafael Cardoso, « Histories of nineteenth-century Brazilian art: a critical review of bibliography, 2000-2012 », Perspective [Online], 2 | 2013, Online since 30 June 2015, connection on 01 October 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/perspective/3891 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ perspective.3891 Histories of nineteenth-century Brazilian art: a critical review of bibliography, 2000-2012 Rafael Cardoso The history of nineteenth-century Brazilian art has undergone major changes over the first years of the twenty-first century. It would be no exaggeration to say that more has been done in the past twelve years than in the entire preceding century, at least in terms of a scholarly approach to the subject. A statement so sweeping needs to be qualified, of course, and it is the aim of the present text to do just that. -

Group Exhibition at Pina Estação Brings Together Works Which Allude to Fictions About the Origin of the World

Group exhibition at Pina Estação brings together works which allude to fictions about the origin of the world Experimental works by Antonio Dias, Carmela Gross, Lothar Baumgarten, Solange Pessoa and Tunga suggest cosmogonic narratives Opening: November 10th, 2018, Saturday, at 11 am Visitation: until February 11th, 2019 Pinacoteca de São Paulo, museum of the São Paulo State Secretariat of Culture, presents, from November 10th, 2018 to February 11th, 2019, the exhibition Invention of Origin, on the fourth floor of Pina Estação. With curatorship by Pinacoteca's Nucleus of Research and Criticism and under general coordination of José Augusto Ribeiro, the museum curator, the group exhibition takes as the starting point the film The Origin of the Night: Amazon Cosmos (1973-77), by the German artist Lothar Baumgarten. The film, rarely exhibited, will be presented alongside a selection of works by four Brazilian artists — Antonio Dias, Carmela Gross, Solange Pessoa and Tunga. In common, the selected works allude to primordial times and actions which could have contributed to the narratives about the origin of life. Shot on 16 mm between 1973 and 1977, The Origin of the Night: Amazon Cosmos, by Lothar Baumgarten, is based on a Tupi myth, registered by the French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, on the origin of the night — which, according to the narrative, used to “sleep” under waters, when animals still did not exist and things had the power of speech. From images captured in the Reno River, between Dusseldorf and Cologne, the artist creates ambiguous situations. “The images are paradoxical, they show a kind of virgin forest in which, however, the waste of human civilization is spread. -

B Ra Silia C Ity T O Ur G U Id E

Brasilia City Tour Guide - Edition # 1 - December 2017 # 1 - December - Edition Guide CityBrasilia Tour Ge t kno i an surprise Ge t kno i an surprise Brasília, JK Bridge (Lago Sul) Get to know Brasilia and be surprised. Brasilia is amazing. And it was intended that way. Since its inauguration on April 21, 1960, the city has been amazing the world with its unique beauty. Conceived by Juscelino Kubitschek, Brasilia is a masterpiece of modern architecture. Its conception results from the work and genius of the urbanist Lucio Costa and the architect Oscar Niemeyer. In addition to that, the city is full of artworks by artists such as Athos Bulcão, Burle Marx, Alfredo Ceschiatti, Marianne Peretti and Bruno Giorgi, which turn it into a unique place. Brasilia is so surprising that it was the first modern and youngest city to be declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1987, only 27 years old. The city is also full of natural riches, with many waterfalls, caves and lagoons, the perfect environments for ecological walks and outdoor sports. During your visit take the chance to get to know, discover and be enchanted with Brasilia. You will realize that the Capital of Brazil will amaze you as well. Access the guide from your smartphone. Use the QR Code to download this guide to your mobile. Ge t kno i an surprise Ge t kno i an surprise BP BRASÍLIAAND ITS TOURISTIC ATTRACTIONS THIS GUIDE IS ORGANIZED IN SEGMENTS AND EACH SEGMENT BY A CORRESPONDING COLOR. CHECK OUT THE MAIN ATTRACTIONS IN THE CITY AND ENJOY YOUR STAY! Historic-Cultural 12 a 21 Architecture 22 a 57 Civic 58 a 75 Nature 76 a 89 Mystic and Religious 90 a 103 Leisure and Entertainment 104 a 123 Tourism Historic- Cultural Get to know it, and be surprised Brasilia has a history that was conceived by great dreamers BP even before its creation. -

Nelson Rodrigues

DADOS DE COPYRIGHT Sobre a obra: A presente obra é disponibilizada pela equipe Le Livros e seus diversos parceiros, com o objetivo de oferecer conteúdo para uso parcial em pesquisas e estudos acadêmicos, bem como o simples teste da qualidade da obra, com o fim exclusivo de compra futura. É expressamente proibida e totalmente repudíavel a venda, aluguel, ou quaisquer uso comercial do presente conteúdo Sobre nós: O Le Livros e seus parceiros disponibilizam conteúdo de dominio publico e propriedade intelectual de forma totalmente gratuita, por acreditar que o conhecimento e a educação devem ser acessíveis e livres a toda e qualquer pessoa. Você pode encontrar mais obras em nosso site: LeLivros.us ou em qualquer um dos sites parceiros apresentados neste link. "Quando o mundo estiver unido na busca do conhecimento, e não mais lutando por dinheiro e poder, então nossa sociedade poderá enfim evoluir a um novo nível." © 2013 by Espólio de Nelson Falcão Rodrigues. Direitos de edição da obra em língua portuguesa no Brasil adquiridos pela EDITORA NOVA FRONTEIRA PARTICIPAÇÕES S.A. Todos os direitos reservados. Nenhuma parte desta obra pode ser apropriada e estocada em sistema de banco de dados ou processo similar, em qualquer forma ou meio, seja eletrônico, de fotocópia, gravação etc., sem a permissão do detentor do copirraite. EDITORA NOVA FRONTEIRA PARTICIPAÇÕES S.A. Rua Nova Jerusalém, 345 — Bonsucesso — 21042-235 Rio de Janeiro — RJ — Brasil Tel.: (21) 3882-8200 — Fax: (21)3882-8212/8313 Capa: Sérgio Campante Fotos de capa: Em cima, torcedores paulistas comemorando gol do Brasil contra o Peru na Copa do Mundo de 1970; em baixo, Jairzinho, Rivelino, Carlos Alberto, Pelé e Wilson Piazza comemoram a vitória do Brasil contra a Itália, na Copa do Mundo de 1970. -

A Arte Como Objeto De Políticas Públicas

FAVOR CORRIGIR O TAMANHO DA LOMBADA DE ACORDO COM A MEDIDA DO MIOLO n. 13 2012 REVISTA OBSERVATÓRIO ITAÚ CULTURAL ITAÚ NÚMERO A arte como objeto de políticas públicas Banco de dados e pesquisas como instrumentos de construção de políticas O mercado das artes no Brasil .13 Artista como trabalhador: alguns elementos de análise itaú cultural avenida paulista 149 [estação brigadeiro do metrô] fone 11 2168 1777 [email protected] www.itaucultural.org.br twitter.com/itaucultural youtube.com/itaucultural Foto: iStockphoto Centro de Documentação e Referência Itaú Cultural Revista Observatório Itaú Cultural : OIC. – n. 13 (set. 2012). – São Paulo : Itaú Cultural, 2012. Semestral. ISSN 1981-125X 1. Política cultural. 2. Gestão cultural. 3. Arte no Brasil. 4. Setores artísticos no Brasil. 5. Pesquisa 6. Produção de conhecimento I. Título: Revista Observatório Itaú Cultural. CDD 353.7 .2 n. 132012 SUMÁRIO .06 AOS LEITORES Eduardo Saron .08 O BANCO DE DaDos DO ItaÚ Cultural: sobre O PassaDO E O Futuro Fabio Cypriano .23 CoNHECER PARA atuar: A IMPortÂNCIA DE ESTUDos E PESQuisas NA FORMULAÇÃO DE POLÍTICAS PÚBLICAS PARA A Cultura Ana Letícia Fialho e Ilana Seltzer Goldstein .33 SOBRE MOZart: soCioloGIA DE UM GÊNIO, DE Norbert ELIAS Dilma Fabri Marão Pichoneri .39 AS ESPECIFICAÇÕES DO MERCADO DE artes Visuais NO BRASIL: ENTREVista COM GeorGE KORNIS Isaura Botelho .55 Arte, Cultura E SEUS DEMÔNios Ana Angélica Albano .63 QuaNDO O toDO ERA MAIS DO QUE A soma DAS Partes: ÁLBUNS, SINGLES E os rumos DA MÚSICA GRAVADA Marcia Tosta Dias .75 CINEMA PARA QUEM PRECisa Francisco Alambert .85 O Direito ao teatro Sérgio de Carvalho .93 MÚSICA, DANÇA E artes Visuais: ASPECtos DO TRABALHO artÍSTICO EM DISCUSSÃO Liliana Rolfsen Petrilli Segnini .3 Revista Observatório Itaú Cultural n. -

Pagu: a Arte No Feminino Como Performance De Si

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS MESTRADO INTERDISCIPLINAR EM PERFORMANCES CULTURAIS LUCIENNE DE ALMEIDA MACHADO PAGU: A ARTE NO FEMININO COMO PERFORMANCE DE SI GOIÂNIA, MARÇO DE 2018. UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS SOCIAIS MESTRADO INTERDISCIPLINAR EM PERFORMANCES CULTURAIS LUCIENNE DE ALMEIDA MACHADO PAGU: A ARTE NO FEMININO COMO PERFORMANCE DE SI Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós- Graduação Interdisciplinar em Performances Culturais, para obtenção do título de Mestra em Performances Culturais pela Universidade Federal de Goiás. Orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Sainy Coelho Borges Veloso. Co-orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Marcela Toledo França de Almeida. GOIÂNIA, MARÇO DE 2018. i ii iii Dedico este trabalho a quem sabe que a pele é fina diante da abertura do peito, que o coração a toca. Por quem sabe que é impossível viver por certos caminhos sem lutar e não brigar pela vida. Para quem entende que a paz e perdão não tem nada de silencioso quando já se viveu algumas guerras. E por quem vive como se sentisse o seu desaparecimento a cada dia, pois as flores não perdem a sua cor, apenas vivem o suficiente para não desbotar. iv AGRADECIMENTOS Não agradecerei neste trabalho a nomes específicos que me atravessaram na minha caminhada enquanto o escrevia, mas sim as experiências que passei a viver nesse período de tempo em que pela primeira vez me permite viver sem ser apenas agredida. Pelos dias que passei a cuidar de mim mesma. Pela minha caminhada em análise que me permitiu entender subjetivamente o que eu buscava quando coloquei essa temática como pesquisa a ser realizada. -

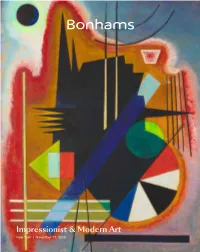

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New York | November 17, 2020 Impressionist & Modern Art New York | Tuesday November 17, 2020 at 5pm EST BONHAMS INQUIRIES BIDS COVID-19 SAFETY STANDARDS 580 Madison Avenue New York Register to bid online by visiting Bonhams’ galleries are currently New York, New York 10022 Molly Ott Ambler www.bonhams.com/26154 subject to government restrictions bonhams.com +1 (917) 206 1636 and arrangements may be subject Bonded pursuant to California [email protected] Alternatively, contact our Client to change. Civil Code Sec. 1812.600; Services department at: Bond No. 57BSBGL0808 Preeya Franklin [email protected] Preview: Lots will be made +1 (917) 206 1617 +1 (212) 644 9001 available for in-person viewing by appointment only. Please [email protected] SALE NUMBER: contact the specialist department IMPORTANT NOTICES 26154 Emily Wilson on impressionist.us@bonhams. Please note that all customers, Lots 1 - 48 +1 (917) 683 9699 com +1 917-206-1696 to arrange irrespective of any previous activity an appointment before visiting [email protected] with Bonhams, are required to have AUCTIONEER our galleries. proof of identity when submitting Ralph Taylor - 2063659-DCA Olivia Grabowsky In accordance with Covid-19 bids. Failure to do this may result in +1 (917) 717 2752 guidelines, it is mandatory that Bonhams & Butterfields your bid not being processed. you wear a face mask and Auctioneers Corp. [email protected] For absentee and telephone bids observe social distancing at all 2077070-DCA times. Additional lot information Los Angeles we require a completed Bidder Registration Form in advance of the and photographs are available Kathy Wong CATALOG: $35 sale.