Setting the Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YOF CITY CLERK's DEPARTMENT VANCOUVER Access to Information

~YOF CITY CLERK'S DEPARTMENT VANCOUVER Access to Information File No.: 04-1000-20-2017-335 October 13, 2017 !S.22(1) Re: Request for Access to Records under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (the "Act") I am responding to your request of September 15, 2017 for: Annexes to the "Coastal Flood Risk Assessment Report" prepared for the City by Northwest Hydraulic Consultants dated December, 2014. The report is available online at the following link http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/CFRA-Phase-1- Final Report.pdf, but the Annexes at the end of the report are blank. All responsive records are attached. Under section 52 of the Act you may ask the Information a: Privacy Commissioner to review any matter related to the City's response to your request. The Act allows you 30 business days from the date you receive this notice to request a review by writing to: Office of the Information a: Privacy Commissioner, [email protected] or by phoning 250·387-5629. If you request a review, please provide the Commissioner's office with: 1) . the request number assigned to your request (#04-1000-20-2017-335); 2) a copy of this letter; 3) a copy of your original request for information sent to the City of Vancouver; and 4) detailed reasons or grounds on which you are seeking the review. Please do not hesitate to contact the Freedom of Information Office at foi@vancouver. ca if you have any questions . City H~ll 453 West 12th Avenue Vancouver BC Y5Y 1V4 vancouver.ca City Clerk's Department tel: 604.873.7276 fax: 604.873.7419 Yours truly, Barbara J. -

BICYCLES Are Unequalled in CONNECTION WE HAVE a FIRST-CLASS CYCLE in the City

•y.'/ VW///J-iw <f>-_^^?-"- W^S^^^^^S^^^i-^. A JOURNAL OF CY©L-lk9 LITERATURE TRADE i&gWS. b VOL. V. MILWAUKEE, Wis., APRIL, 1894. >v'if8%'v v NO. 1. YcYevs ©cordis AVc invito iiispi-'ution of our lino. Catalogues fpno al lluniblor Agimdes. GORMULLY & JEFFERY MFG. CO. (..'MICA (JO. BOSTON. WASHINGTON. NKW YfMK. COVKNTUY, KNllLANI). JOHN MEUNIER GUN CO., AGENTS FOR MILWAUKEE, 272 WEST WATER STREET. MENTION THE "PNSUS." THE PNEUMATIC. H. L. KASTEN & CO. STEARNS 517 GRAND AVE. MILWAUKEE E Don't Take A. Our Word s R For It N Come S and See E ..*••' the Wheel H. L. KASTEN & CO. 517 GRAND AVE. M MILWAUKEE STEARNS MENTION THE PNEUS" IN CONNECTION WITH OUR Reitzner - WicKs Gucie Go. =TYPEWRITER=BUSINESS Successors to REITZNER-PRICHARD CYCLE CO. WE HAVE SECURED THE AGENCY FOR THE WELL-KNOWN AND ... MANUFACTURERS OF... MERCURY ....CELEBRATED.... FOWLER FLIERS WHEELS AND AGENTS FOR-, The Celebrated HARRY JAMES CYCLES. A COMPLETE LINE OF THESE MACHINES CAN BE SEEN The CLEVELAND and SMALLEY Wheels. AT OUR STORE 414 Broadway = Milwaukee, LOOK TO YOUR WHEELS WHEELS FITTED WITH MORGAN & WRIGHT, PALMER AND Q..&, J, TIRES. WOOD OR STEEL RIMS, Our Facilities for REPAIRING BICYCLES are Unequalled IN CONNECTION WE HAVE A FIRST-CLASS CYCLE in the City. REPAIR SHOP. 444 National Ave., Milwaukee. Badoer Typewriter * Stationery Go. MENTION THE "PNEUS. MENTION THE "pNEUS.' E. D. HAVEN, Manager. THE PNEUMATIC. -Photographic-Supplies- FOR SALE FOR AMATEURS. A BARGAIN JOHN B. BANGS & 60. 375 MILWAUKEE STREET Brand new ARROW Safety Aoaiomy of Mooio Bulldlnjj, KODAKS REFILLED, Bicycle, same as was sold all last DEVELOPING AND PRINTING. -

UNIFIED WORK PROGRAM (UWP) for NORTHEASTERN ILLINOIS Quarterly Progress Report- FY 2011 1St Quarter

UNIFIED WORK PROGRAM (UWP) FOR NORTHEASTERN ILLINOIS Quarterly Progress Report- FY 2011 1st Quarter UNIFIED WORK PROGRAM (UWP) FOR NORTHEASTERN ILLINOIS Quarterly Progress Report- FY 2011 1st Quarter TABLE OF CONTENTS (BY RECIPIENT AGENCY) CMAP................................................................................................................................... 2 City of Chicago................................................................................................................... 56 CTA....................................................................................................................................... 75 Regional Council of Mayors............................................................................................ 94 Lake County........................................................................................................................ 98 McHenry County................................................................................................................ 105 Metra..................................................................................................................................... 108 Pace........................................................................................................................................ 117 RTA........................................................................................................................................ 132 West Central Municipal Conference............................................................................. -

Design and Construction of MSE Slopes Associated with the Port Mann Bridge, Vancouver, British Columbia

Design and Construction of MSE Slopes Associated With the Port Mann Bridge, Vancouver, British Columbia Gordon Fung, E.I.T. Geotechnical Engineer, MEG Consulting Ltd., Richmond, BC. German Cajigas, M. Eng., P. Eng. Regional Design Engineer, Tensar International Corporation, Burnaby, BC. Ryan Tones, P. Eng. Project Sponsor, Kiewit Flatiron General Partnership, Vancouver, BC Dan MacDonald, P. Eng. Manager, MSE Group, Nilex, Burnaby, BC. John R. Kerr, M. Eng., P. Eng. Regional Manager, Tensar International Corporation, Calgary, Alberta Ender Parra C., Ph.D. Principal, MEG Consulting Ltd., Richmond, BC. John P. Sully, Ph.D., P.Eng. Principal, MEG Consulting Ltd., Richmond, BC. ABSTRACT This paper presents the seismic modeling performed for the design of a 9-m high 70 o SierraSlope® with an upper 2H:1V fill slope up to 4 m high. The SierraSlope®, a Mechanically Stabilised Earth (MSE) reinforced soil slope using geogrids, was introduced by Tensar International Corporation (Tensar). The facing of the slope is composed of welded wire mesh forms with a synthetic wrap system of Tensar Biaxial Geogrid. The FLAC (Fast Lagrangian Analysis of Continua) finite difference program was used to model the SierraSlope® under seismic loading conditions. The FLAC analyses are considered to provide a comparison and evaluation of the standard design approaches as well as an additional insight into the seismic performance of the SierraSlope®. (Coquitlam), Bridge (the site of the new bridge at the Project Overview Fraser River Crossing), and East (Surrey, Langley). The critical SierraSlope® section considered in the The Port Mann/Highway 1 Improvement Project is a $2.4 dynamic soil structure interaction analysis is located in billion design-build project that includes the widening of 37 Central Segment’s Cape Horn Interchange on the western kilometers of Highway 1, from McGill Street to 216th Street approach to the new Port Mann Bridge. -

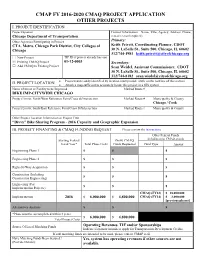

Cmap Fy 2016-2020 Cmaq Project Application Other Projects I

CMAP FY 2016-2020 CMAQ PROJECT APPLICATION OTHER PROJECTS I. PROJECT IDENTIFICATION Project Sponsor Contact Information – Name, Title, Agency, Address, Phone, Chicago Department of Transportation e-mail (e-mail required) Other Agencies Participating in Project Primary: CTA, Metra, Chicago Park District, City Colleges of Keith Privett, Coordinating Planner, CDOT Chicago 30 N. LaSalle St., Suite 500, Chicago, IL 60602 312/744-1981 [email protected] ☐ New Project TIP ID if project already has one ☒ Existing CMAQ Project 01-12-0003 Secondary: ☐ Add CMAQ to Existing Project Sean We idel, Assistant Commissioner, CDOT 30 N. LaSalle St., Suite 500, Chicago, IL 60602 312/744-8182 [email protected] II. PROJECT LOCATION • Projects not readily identified by location must provide a title on the last line of this section • Attach a map sufficient to accurately locate this project in a GIS system Name of Street or Facility to be Improved Marked Route # BIKE IMP-CITYWIDE CHICAGO Project Limits: North/West Reference Point/Cross St/Intersection Marked Route # Municipality & County Chicago / Cook Project Limits: South/East Reference Point/Cross St/Intersection Marked Route # Municipality & County Other Project Location Information or Project Title “Divvy” Bike Sharing Program - 2016 Capacity and Geographic Expansion III. PROJECT FINANCING & CMAQ FUNDING REQUEST Please review the instructions. Other Federal Funds Starting Federal (New) CMAQ Including prior CMAQ awards Fiscal Year* Total Phase Costs Funds Requested Fund Type Amount -

IMPROVED APPROACHES to MANAGE ROAD SAFETY INFRASTRUCTURE by PAUL DE LEUR

IMPROVED APPROACHES TO MANAGE ROAD SAFETY INFRASTRUCTURE by PAUL DE LEUR B Sc., University of Saskatchewan, 1988 M.A.Sc, University of British Columbia, 1992 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Civil Engineering We accept this thesis as conforming To the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA January 2001 © Paul de Leur, 2001 Authorization: In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at The University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available reference and study. I further agree that the permission for the extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purpose may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Civil Engineering The University of British Columbia 2324 Main Mall Vancouver, BC Canada, V6T1Z4 ||§ University of British Columbia Preliminary Pages Improving the Management of Road Safety ABSTRACT Due to the importance of road safety, most road authorities and safety agencies employ some type of road safety management program, designed to improve the safety performance for the system users. One road safety management program is delivered through road planning and engineering, aimed to improve the road design features to reduce the frequency and/or severity of collisions. These road safety management programs can be divided into two categories: reactive road safety initiatives (i.e., responding to existing road safety problems) and proactive road safety initiatives (i.e., actions taken to prevent the emergence of problems). -

573 Sherling Place Port Coquitlam, Bc

FOR LEASE UNIT 1165 573 SHERLING PLACE PORT COQUITLAM, BC BRAND NEW 3,051 SF INDUSTRIAL LEASE OPPORTUNITY Kevin Volz Rick Eastman Personal Real Estate Corporation Personal Real Estate Corporation Vice President, Industrial Senior Vice President, Industrial 604 640 5851 604 640 5863 [email protected] [email protected] Suite 700 - 700 West Georgia Street / PO Box 10023, Pacifi c Centre / Vancouver, BC V7Y 1A1 / 604 683 3111 / 1 877 788 3111 / cushmanwakefi eld.com FOR LEASE UNIT 1165 573 SHERLING PLACE PORT COQUITLAM, BC LOCATION LEASE RATE 573 Sherling Place, Port Coquitlam is situated at the high exposure $3,295.00 per month, plus GST corner of Fremont Street and Sherling Place in the brand new River’s Edge Business Park in the heart of the Dominion Triangle area. With close proximity to the Pitt River Bridge and Golden Ears Bridge to ADDITIONAL RENT (2017) the east, Coast Meridian Overpass to the west and being only minutes Estimated at $1,057.94 per month, plus GST from the new Cape Horn Interchange, Port Mann Bridge and Highway #1. River’s Edge Business Park off ers a superb location for warehouse and distribution, with excellent profi le for accessory retail and offi ce. COMMENTS Minimum 3 year lease term or longer. FEATURES • High end architecturally designed building • Extensive ground & mezzanine level glazing • 24’ clear ceiling height • 500 lbs per square foot fl oor load rating • ESFR rated sprinkler system • T-5 fl uorescent lighting • 100 amp, 347/600 volt, 3 phase electrical service • Rear grade level loading • Three (3) parking spaces • Forced airgas warehouse heaters AVAILABLE AREA Main Floor Warehouse 2,088 sf Mezzanine Floor 963 sf Total Available Area 3,051 sf ZONING M-3 (Clean Industrial) zoning allows for uses including clean manufacturing, high tech, commercial indoor recreation, warehousing and select offi ce and retail uses. -

Student Cycling in Chicago,X-Default

Ride a Bike! A message from a cyclist - Mayor Richard M. Daley Bicycling is a great way to get around campus and around town. It's healthy, eco- nomical, environmentally friendly and a wonderful way to discover Chicago. From locking your bike to fixing a flat tire, you'll find all sorts of useful information inside this Student Cycling in Chicago book- let. Riding a bike as a student can lead to a life-long transportation choice that's good for you, your community and the enviroment. I invite you to review this booklet and discover for yourself why Chicago is a great city for bicycling. Richard M. Daley Mayor STUDENT CYCLING IN CHICAGO www.ChicagoBikes.org 1 Buying a Bike When buying a bike wear clothes like the ones you plan to bike in regularly and take a test ride If your bike budget is like the riding you’ll do around school and the small consider buying a used bike. Used city. Also consider these things: bikes can be found at · What kind of riding you plan to do and what thrift shops and yard type of bike is best suited for you. s ale s for cheap. · The cost of the bike. WorkingBikesCooperative · The cost of a lock, lights, helmet and other has a used bike sale accessories like a rack and fenders. on weekends. Go to · Whether you can exchange parts for www.workingbikes.org better fit or use. for more information. · Guarantees and warranties on the purchase. If you plan to buy a · Bike shop quality and service. -

Industrial/Office Unit 2140-570 Sherling Place Port Coquitlam

FOR SALE | INDUSTRIAL/OFFICE UNIT 2140-570 SHERLING PLACE PORT COQUITLAM X 4,650 SF Office/warehouse unit X River Edge Business Park Location Highlights Situated in the heart of the Dominion Triangle area of Port Coquitlam, 570 Sherling Place X Concrete tilt-up with insulated exterior is located at the high exposure corner of Sherling Place and the Fremont Connector in the walls brand new River’s Edge Business Park. With close proximity to the Pitt River Bridge and the X Grade level loading Golden Ears Bridge to the east, the Coast Meridian Overpass to the west and being only X Approx. 22’ foot warehouse ceiling minutes from the Cape Horn Interchange, the Port Mann Bridge and Highway #1, River’s heights Edge Business Park offers a superb location for warehousing and distribution. Surrounded X 3-phase electrical power by the Fremont Village Shopping Centre, Mosaic’s Dominion residential development, X Five (5) Parking stalls with loading area Carnoustie Golf Club and recreational riverside parks and trails. River’s Edge Business Park X High exposure to Fremont Connector also offers unparalleled retail and lifestyle amenities. X High end architechually designed building X Fully finished offices over two levels with HVAC Ryan Barichello Chris McIntyre D 604.630.3371 C 604.889.4146 Personal Real Estate Corporation [email protected] D 604.630.3392 C 604.889.0699 [email protected] 475 West Georgia Street, Suite 800 | Vancouver, BC V6B 4M9 | 604.684.7117 | leevancouver.com FOR SALE | INDUSTRIAL/OFFICE UNIT 2140-570 SHERLING PLACE PORT COQUITLAM Zoning Strata Fees Asking Price M3 Industrial - Allows for clean manufacturiing, high tech, service $689.47 $1,930,000.00 and distribution use Taxes & Operating Costs (2019) Availability Features $16,540.94 Contact Agent X Fully finished offices over two levels with HVAC X Private offices, boardroom, lunchroom with kitchen and Floor Plans 100 WARE reception/showroom areas. -

Pedestrian Plan Department of Transportation

Chicago Pedestrian Plan Department of Transportation DRAFT T ABLE OF C ON T EN T S Letter from the Mayor and Commissioner 7 What We Heard 10 Tools for Safer Streets 16 Safety 36 Connectivity 64 Livability 86 Health 96 Making It Happen 108 3 4 OFFICE OF THE MAYOR CITY OF CHICAGO 121 N. LaSalle Street • Chicago, Illinois 60602 www.cityofchicago.org • @chicagosmayor Dear Fellow Chicagoans, Chicago’s remarkable pedestrian streets make our city a place where people want to live, work and play. The pedestrian experience is critical to the city and its future. From the hundreds of thousands of people that walk in the Loop every day, to the millions of riders of our trains and buses, to the bustling activity in our neighborhood commercial corridors, the safety of pedestrians has always been a building block to the city’s success. We are committed to protecting these vital users of our transportation system; safe, pedestrian-friendly streets are a priority for my administration. We will create a culture of safety and respect by addressing street design and behavior through education, engineering and enforcement. Pedestrians are vital to both the economic and physical health of Chicago. Building more and better pedestrian spaces will help businesses grow and encourage further development of our workforce for those who want to live in a walkable, transit- friendly city. Additionally, by encouraging more people to walk, we can improve our collective health and quality of life. I am excited about the action steps identified in the Chicago Pedestrian Plan. This comprehensive agenda addresses all aspects of the city’s pedestrian experience. -

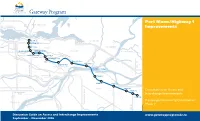

Port Mann/Highway 1 Improvements

Port Mann/Highway 1 Improvements McGill St. Hastings St. First Ave. Port Coquitlam Boundary Rd. Willingdon Ave. Grandview Hwy. Sprott St. Kensington Ave. Brunette Ave. Cape Horn Gaglardi Way Port Mann Bridge 152nd St. 160th St. 176th St. 192nd St. 200th St. Consultation on Access and Interchange Improvements 216th St. Pre-design Community Consultation Phase 2 200 St Discussion Guide on Access and Interchange Improvements www.gatewayprogram.bc.ca September – November 2006 CONSULTATION ON ACCESS AND INTERCHANGE IMPROVEMENTS: PRE-DESIGN COMMUNITY CONSULTATION PHASE 2 The Ministry of Transportation conducts community consultations at three design stages, including: Pre-design Consultation: Phase 1 Pre-design Consultation: Phase 2 Preliminary Design Consultation Detailed Design Consultation February – April 2006 September – November 2006 2008 2009 Pre-design consultation discussion topics This phase of consultation focuses on With basic pre-design components Detailed design consultation generally focuses included goals for interchange upgrades, proposed conceptual improvements determined, consultation on preliminary on fewer but more specifi c treatments, such congestion reduction measures such as high to existing and new interchanges and design discusses refi nements to interchanges as detailed interchange and access features, occupancy vehicle lanes (HOV) and transit overpasses. These proposed modifi cations and accesses, lane use, specifi cs of congestion lighting and landscaping. This phase also priority on-ramps, commercial vehicle priority and upgrades would improve safety, access reduction measures and other key features. involves more fi nancial and technical analysis access to on-ramps, potential tolling, and and connections across the highway, support to confi rm that designs are fi nancially and improvements to the cycling network. -

573 Sherling Place Port Coquitlam, Bc

FOR LEASE UNIT 1115 573 SHERLING PLACE PORT COQUITLAM, BC 1,892 SF SHELL WAREHOUSE Kevin Volz Rick Eastman Personal Real Estate Corporation Personal Real Estate Corporation Vice President, Industrial Executive Vice President, Industrial 604 640 5851 604 640 5863 [email protected] [email protected] Suite 700 - 700 West Georgia Street / PO Box 10023, Pacifi c Centre / Vancouver, BC V7Y 1A1 / 604 683 3111 / 1 877 788 3111 / cushmanwakefi eld.com FOR LEASE UNIT 1115 573 SHERLING PLACE PORT COQUITLAM, BC LOCATION LEASE RATE The subject property is situated at the high exposure corner of $2,672.45 per month, net, plus GST (shell) Fremont Street and Sherling Place in the River’s Edge Business Centre in the heart of the Dominion Triangle area. It is within close proximity to the Pitt River Bridge and Golden Ears Bridge to the east, Coast ADDITIONAL RENT (2020) Meridian Overpass to the west and being only minutes from the Estimated at $1,102.55 per month, plus GST Cape Horn Interchange, Port Mann Bridge and Highway #1. River’s Edge Business Centre off ers a superb location for warehouse and distribution, with excellent profi le for accessory retail and offi ce. ZONING M-3 (Clean Industrial) zoning allows for uses including clean manufacturing, high tech, commercial indoor recreation, warehousing and select offi ce and retail uses. BUILDING FEATURES • Concrete tilt-up construction • High end architecturally designed building • Extensive ground & mezzanine level glazing • Minimum 24’ clear ceiling height • 500 lbs per square foot fl oor load rating • ESFR rated sprinkler system • Forced air gas warehouse heater • T-5 fl uorescent lighting • 100 amp, 347/600 volt, 3 phase electrical service • One (1) rear 12’ x 12’ grade level loading door with generous truck maneuvering • Three (3) parking spaces AVAILABLE AREA Shell Warehouse 1,892 sf AVAILABILITY September 1, 2020 1185 1180 1175 1170 1165 1145 1140 1135 1130 1125 1120 1115 1110 1105 35,712 S.F.