THE ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE of the LOWER FRASER RIVER July 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fraser River from Source to Mouth

FRASER RIVER FROM SOURCE TO MOUTH September 5, 2017 - 11 Days Fares Per Person: $3395 double/twin $4065 single $3210 triple > Please add 5% GST. Early Bookers: $160 discount on first 12 seats; $80 on next 8 > Experience Points: Earn 76 points from this tour. Redeem 76 points if you book by July 5. Includes Flight from Victoria to Kelowna St. John the Divine Church in Yale Coach transportation for 10 days Harrison Hot Springs pools 10 nights of accommodation & hotel taxes Copper Room music & dancing with Jones Boys Helicopter to the source of the Fraser River Fraser River Safari boat excursion Fraser River raft float trip (no white water) Paddlewheeler cruise from New Westminster Huble Homestead tour to the mouth of the Fraser River Farwell Canyon and pictographs Gulf of Georgia Cannery National Historic Site Cariboo Chilcotin Museum Transfer from New Westminster to Victoria Hat Creek Historic Ranch and roadhouse tour Knowledgeable tour director Hell’s Gate Airtram Luggage handling at hotels Alexandra Suspension Bridge 21 meals: 8 breakfasts, 9 lunches, 4 dinners Activity Level This is a unique tour with lots of activity and time outdoors while you experience many aspects of the Fraser River. The trip to the source of the Fraser requires getting in and out of a helicopter, and walking about ½ km in an alpine meadow at 2,000 metres altitude. On other days, you are boarding a large raft and two boats. Walks in- clude Farwell Canyon pictographs, Alexandra Bridge, and the boat dock to Kilby Store. This tour has activity ranging from somewhat rigorous to sedentary. -

Ecosystem Status and Trends Report for the Strait of Georgia Ecozone

C S A S S C C S Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat Secrétariat canadien de consultation scientifique Research Document 2010/010 Document de recherche 2010/010 Ecosystem Status and Trends Report Rapport de l’état des écosystèmes et for the Strait of Georgia Ecozone des tendances pour l’écozone du détroit de Georgie Sophia C. Johannessen and Bruce McCarter Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Institute of Ocean Sciences 9860 W. Saanich Rd. P.O. Box 6000, Sidney, B.C. V8L 4B2 This series documents the scientific basis for the La présente série documente les fondements evaluation of aquatic resources and ecosystems scientifiques des évaluations des ressources et in Canada. As such, it addresses the issues of des écosystèmes aquatiques du Canada. Elle the day in the time frames required and the traite des problèmes courants selon les documents it contains are not intended as échéanciers dictés. Les documents qu’elle definitive statements on the subjects addressed contient ne doivent pas être considérés comme but rather as progress reports on ongoing des énoncés définitifs sur les sujets traités, mais investigations. plutôt comme des rapports d’étape sur les études en cours. Research documents are produced in the official Les documents de recherche sont publiés dans language in which they are provided to the la langue officielle utilisée dans le manuscrit Secretariat. envoyé au Secrétariat. This document is available on the Internet at: Ce document est disponible sur l’Internet à: http://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/csas/ ISSN 1499-3848 (Printed / Imprimé) ISSN 1919-5044 (Online / En ligne) © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2010 © Sa Majesté la Reine du Chef du Canada, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS Highlights 1 Drivers of change 2 Status and trends indicators 2 1. -

YOF CITY CLERK's DEPARTMENT VANCOUVER Access to Information

~YOF CITY CLERK'S DEPARTMENT VANCOUVER Access to Information File No.: 04-1000-20-2017-335 October 13, 2017 !S.22(1) Re: Request for Access to Records under the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (the "Act") I am responding to your request of September 15, 2017 for: Annexes to the "Coastal Flood Risk Assessment Report" prepared for the City by Northwest Hydraulic Consultants dated December, 2014. The report is available online at the following link http://vancouver.ca/files/cov/CFRA-Phase-1- Final Report.pdf, but the Annexes at the end of the report are blank. All responsive records are attached. Under section 52 of the Act you may ask the Information a: Privacy Commissioner to review any matter related to the City's response to your request. The Act allows you 30 business days from the date you receive this notice to request a review by writing to: Office of the Information a: Privacy Commissioner, [email protected] or by phoning 250·387-5629. If you request a review, please provide the Commissioner's office with: 1) . the request number assigned to your request (#04-1000-20-2017-335); 2) a copy of this letter; 3) a copy of your original request for information sent to the City of Vancouver; and 4) detailed reasons or grounds on which you are seeking the review. Please do not hesitate to contact the Freedom of Information Office at foi@vancouver. ca if you have any questions . City H~ll 453 West 12th Avenue Vancouver BC Y5Y 1V4 vancouver.ca City Clerk's Department tel: 604.873.7276 fax: 604.873.7419 Yours truly, Barbara J. -

Greater Vancouver Regional District

Greater Vancouver Regional District The Greater Vancouver Regional District (GVRD) is a partnership of 21 municipalities and one electoral area that make up the metropolitan area of Greater Vancouver.* The first meeting of the GVRD's Board of Directors was held July 12, 1967, at a time when there were 950,000 people living in the Lower Mainland. Today, that number has doubled to more than two million residents, and is expected to grow to 2.7 million by 2021. GVRD's role in the Lower Mainland Amidst this growth, the GVRD's role is to: • deliver essential utility services like drinking water, sewage treatment, recycling and garbage disposal that are most economical and effective to provide on a regional basis • protect and enhance the quality of life in our region by managing and planning growth and development, as well as protecting air quality and green spaces. GVRD structure Because the GVRD serves as a collective voice and a decision-making body on a variety of issues, the system is structured so that each member municipality has a say in how the GVRD is run. The GVRD's Board of directors is comprised of mayors and councillors from the member municipalities, on a Representation by Population basis. GVRD departments are composed of staff and managers who are joined by a shared vision and common goals. Other GVRD entities Under the umbrella of the GVRD, there are four separate legal entities: the Greater Vancouver Water District (GVWD); the Greater Vancouver Sewerage and Drainage District (GVS&DD); the Greater Vancouver Housing Corporation (GVHC), and the Greater Vancouver Regional District. -

Okanagan Valley

OKANAGAN VALLEY DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY HIGHLIGHTS MYRA CANYON Photo: Grant Harder THANK WHAT’S YOU INSIDE The Okanagan Valley Destination Thank you to our tourism partners 1. INTRODUCTION Development Strategy is the outcome who participated in the process by of a nineteen-month, iterative process attending community meetings, 2. REALIZING THE POTENTIAL of gathering, synthesizing, and participating in surveys and validating information with tourism interviews, engaging in follow-up 3. AT A GLANCE partners about the current status conversations, and forwarding 4. GEARING UP and future direction of tourism in relevant documents and insights. the Okanagan Valley planning area. Special thanks to the members of the Working Group, as well as the We thank the Syilx people and the facilitator of the destination Okanagan Nation on whose traditional development process. territories we gathered for meetings in Kelowna and Summerland. OKANAGAN VALLEY | 2 1 INTRODUCTION WHY A STRATEGY? District, and part of electoral area E (West Boundary) the creation of a provincial destination development of the Regional District of Kootenay Boundary. strategy thereby ensuring a truly integrated and The Okanagan Valley Destination Development Municipalities include Lake Country, Kelowna, West cohesive combination of bottom-up and top-down Strategy was developed to enhance the competitiveness Kelowna, Peachland, Summerland, Penticton, Oliver, destination planning. of the Okanagan Valley planning area over the next 10 Keremeos, and Osoyoos. The planning area includes years and beyond. The strategy was developed as part most of the Okanagan Valley, Sakha Lake, and the of Destination BC’s Destination Development Program Okanagan River. A KEY IMPERATIVE to support and guide the long-term growth of tourism in British Columbia. -

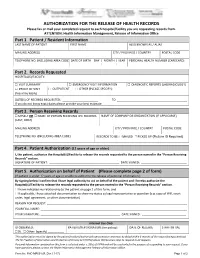

AUTHORIZATION for the RELEASE of HEALTH RECORDS Please Fax Or Mail Your Completed Request to Each Hospital/Facility You Are Requesting Records From

AUTHORIZATION FOR THE RELEASE OF HEALTH RECORDS Please fax or mail your completed request to each hospital/facility you are requesting records from. ATTENTION: Health Information Management, Release of Information Office Part 1. Patient / Resident Information LAST NAME OF PATIENT FIRST NAME ALSO KNOWN AS / ALIAS MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) DATE OF BIRTH DAY | MONTH | YEAR PERSONAL HEALTH NUMBER (CARECARD) | | Part 2. Records Requested HOSPITAL(S)/FACILITY: □ VISIT SUMMARY □ EMERGENCY VISIT INFORMATION □ DIAGNOSTIC REPORTS (LAB/RADIOLOGY) □ PROOF OF VISIT □ OUTPATIENT □ OTHER (PLEASE SPECIFY): (fees may apply) DATE(S) OF RECORDS REQUESTED: ______________________ TO ___________________________________________ If you do not know exact dates please provide your best estimate Part 3. Person Receiving Records □ MYSELF OR □ NAME OF PERSON RECEIVING THE RECORDS NAME OF COMPANY OR ORGANIZATION (IF APPLICABLE) (LAST, FIRST) MAILING ADDRESS CITY / PROVINCE / COUNTRY POSTAL CODE TELEPHONE NO. (INCLUDING AREA CODE) RECORDS TO BE: □ MAILED □ PICKED UP (Picture ID Required) Part 4. Patient Authorization (12 years of age or older) I, the patient, authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. SIGNATURE OF PATIENT: ___________________________________________ DATE SIGNED: ____________________________ Part 5. Authorization on behalf of Patient (Please complete page 2 of form) (If patient is under 12 years of age or unable to authorize the release of personal information.) By signing below I confirm that I have legal authority to act on behalf of the patient and I hereby authorize the Hospital(s)/Facility to release the records requested to the person named in the “Person Receiving Records” section. -

Ministry of Attorney General Court Services Online New Case Report 01-SEP-2021 to 03-SEP-2021

Ministry of Attorney General Page: 1 of 14 Court Services Online New Case Report 29-SEP-2021 TO 01-OCT-2021 File Contains Court Location File Number Classification of File Style of Cause Electronic Docs Date Opened Abbotsford Law 24658 Provincial-Small Claims HILTON, Pamela vs YES 28-SEP-2021 Courts SJODEN, Anne 01314 Supreme-Motor Vehicle NAIR, Appu vs SINGH, YES 09-SEP-2021 Accidents Satwinder 01313 Supreme-Supreme Civil LASLO, Allen vs LASLO, YES 15-SEP-2021 (General) Donald 01315 Supreme-Supreme Civil JONES, Chandra vs YES 10-SEP-2021 (General) 9426396 CANADA LIMITED OPERATING AT DEEPU'S NO FRILLS Campbell River Law 15224 Supreme-Motor Vehicle REMPEL, Rosa vs BRAR, YES 01-OCT-2021 Courts Accidents Mohinder 14896 Supreme-Probate PHILLIPS, Jordon vs YES 27-SEP-2021 PHILLIPS, John 14897 Supreme-Probate CORMIER, Debra vs YES 28-SEP-2021 NELSON, David 15223 Supreme-Supreme Civil REMPEL, Rosa vs YES 01-OCT-2021 (General) INSURANCE CORPORATION OF BRITISH COLUMBIA Chilliwack Law 39013 Supreme-Foreclosure EQUITABLE BANK vs YES 29-SEP-2021 Courts MCGRUGAN, Tyler 39011 Supreme-Motor Vehicle MICHELL, Todd vs YES 28-SEP-2021 Accidents MICHELL, Sarah 23116 Supreme-Probate GILLIES, Lubow vs GILLIES, YES 29-SEP-2021 Gary 23117 Supreme-Probate SIVILAY, Tony vs SIVILAY, YES 29-SEP-2021 Samsay 23118 Supreme-Probate MCLACHLAN, Mary vs YES 29-SEP-2021 MCLACHLAN, Duncan 39012 Supreme-Supreme Civil MAYO, Kristin vs ESTATE YES 29-SEP-2021 (General) OF ALLAN REGINALD WILLIAM MAYO Courtenay Law 02779 Provincial-Small Claims HARPELL, Jonathan vs YES 29-SEP-2021 -

Prehistoric Mobile Art from the Mid-Fraser and Thompson River Areas ARNOUDSTRYD

CHAPTER9 Prehistoric Mobile Art from the Mid-Fraser and Thompson River Areas ARNOUDSTRYD he study of ethnographic and archaeological art the majority of archaeological work in the Plateau but from interior British Columbia has never received also appear to be the "heartland" of Plateau art develop Tthe attention which has been lavished on the art of ment as predicted by Duff (1956). Special attention will be the British Columbia coast. This was inevitable given the focused on the previously undescribed carvings recovered impressive nature of coastal art and the relative paucity in recent excavations by the author along the Fraser River of its counterpart. Nevertheless, some understanding of near the town of Lillooet. the scope and significance of this art has been attained, Reports and collections from seventy-one archaeologi largely due to the turn of the century work by members cal sites were checked for mobile art. They represent all of the Jesup North Pacific Expedition (Teit 1900, 1906, the prehistoric sites excavated and reported as of Spring 1909; Boas, 1900; Smith, 1899, 1900) and the more recent 1976, although some unintentional omissions may have studies by Duff (1956, 1975). Further, archaeological occurred. The historic components of continually oc excavations over the last fifteen years (e.g., Sanger 1968a, cupied sites were deleted and sites with assemblages of 1968b, 1970; Stryd 1972, 1973) have shown that prehistoric less than ten artifacts were also omitted. The most notable Plateau art was more extensive than previously thought, exclusions from this study are most of Smith's (1899) and that ethnographic carving represented a degeneration Lytton excavation data which are not quantified or listed from a late prehistoric developmental climax. -

A Nitrogen Budget for the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia, with Emphasis on Particulate Nitrogen and Dissolved Inorganic Nitrogen

Biogeosciences, 10, 7179–7194, 2013 Open Access www.biogeosciences.net/10/7179/2013/ doi:10.5194/bg-10-7179-2013 Biogeosciences © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. A nitrogen budget for the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia, with emphasis on particulate nitrogen and dissolved inorganic nitrogen J. N. Sutton1,2, S. C. Johannessen1, and R. W. Macdonald1 1Institute of Ocean Sciences, Fisheries and Oceans Canada, 9860 West Saanich Road, P.O. Box 6000, Sidney, British Columbia, V8L 4B2, Canada 2Department of Earth and Planetary Science, University of California, Berkeley, California, 94720, USA Correspondence to: J. N. Sutton ([email protected]) Received: 6 March 2013 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 23 April 2013 Revised: 29 September 2013 – Accepted: 10 October 2013 – Published: 12 November 2013 Abstract. Balanced budgets for dissolved inorganic N (DIN) 1 Introduction and particulate N (PN) were constructed for the Strait of Georgia (SoG), a semi-enclosed coastal sea off the west coast of British Columbia, Canada. The dominant control on the The nitrogen (N) cycle is a crucial underpinning of marine N budget is the advection of DIN into and out of the SoG biological productivity (Gruber and Galloway, 2008). Dur- via Haro Strait. The annual influx of DIN by advection from ing the past 150 yr, the global N cycle has been dramati- the Pacific Ocean is 29 990 (±19 500) Mmol yr−1. The DIN cally changed by human activities that have loaded reactive N flux advected out of the SoG is 24 300 (±15 500) Mmol yr−1. into ecosystems in amounts that rival natural sources (Rabal- Most of the DIN that enters the SoG (∼ 23 400 Mmol yr−1) ais, 2002; Galloway et al., 2004). -

Fraser Valley Geotour: Bedrock, Glacial Deposits, Recent Sediments, Geological Hazards and Applied Geology: Sumas Mountain and Abbotsford Area

Fraser Valley Geotour: Bedrock, Glacial Deposits, Recent Sediments, Geological Hazards and Applied Geology: Sumas Mountain and Abbotsford Area A collaboration in support of teachers in and around Abbotsford, B.C. in celebration of National Science and Technology Week October 25, 2013 MineralsEd and Natural Resources Canada, Geological Survey of Canada Led by David Huntley, PhD, GSC and David Thompson, P Geo 1 2 Fraser Valley Geotour Introduction Welcome to the Fraser Valley Geotour! Learning about our Earth, geological processes and features, and the relevance of it all to our lives is really best addressed outside of a classroom. Our entire province is the laboratory for geological studies. The landscape and rocks in the Fraser Valley record many natural Earth processes and reveal a large part of the geologic history of this part of BC – a unique part of the Canadian Cordillera. This professional development field trip for teachers looks at a selection of the bedrock and overlying surficial sediments in the Abbotsford area that evidence these geologic processes over time. The stops highlight key features that are part of the geological story - demonstrating surface processes, recording rock – forming processes, revealing the tectonic history, and evidence of glaciation. The important interplay of these phenomena and later human activity is highlighted along the way. It is designed to build your understanding of Earth Science and its relevance to our lives to support your teaching related topics in your classroom. Acknowledgments We would like to thank our partners, the individuals who led the tour to share their expertise, build interest in the natural history of the area, and inspire your teaching. -

Comparing Municipal Government Finances in Metro Vancouver

Comparing Municipal Government Finances in Metro Vancouver October 2014 WEST DISTRICT OF VANCOUVER NORTH VANCOUVER CITY OF NORTH VANCOUVER COQUITLAM PORT MOODY BURNABY PORT COQUITLAM VANCOUVER PITT MAPLE MEADOWS RIDGE NEW WESTMINSTER RICHMOND DISTRICT OF LANGLEY DELTA SURREY CITY OF LANGLEY WHITE ROCK Charles Lammam, Joel Emes, and Hugh MacIntyre fraserinstitute.org Contents Summary / iii Introduction / 1 1 Background / 3 2 Municipal Spending / 7 3 Municipal Revenue / 15 4 Municipal Debt and Interest Expenditures / 35 Conclusion / 39 Appendix 1 Description of the Local Government Statistics / 41 Appendix 2 Spending and Revenue per Person by Major Category / 45 Appendix 3 Municipal Summary Profiles, 2012 / 47 References / 56 About the Authors / 59 Publishing Information 60 Acknowledgments / 60 Supporting the Fraser Institute 61 Purpose, Funding, and Independence / 62 About the Fraser Institute / 63 Editorial Advisory Board / 64 fraserinstitute.org / i fraserinstitute.org Summary Municipal governments play an important role in the lives of British Columbians by providing important services and collecting taxes. But municipal finances do not receive the same degree of public scrutiny as more senior governments. This can pose a problem for taxpayers and voters who want to understand how their municipal government performs, especially compared to other municipalities. To help create awareness and encourage debate, this report provides a summary analysis of important financial information for 17 of the 21 municipal- ities in Metro Vancouver, spanning a 10-year period (2002–2012). The intention is not to make an assessment of any municipality’s finances—for instance, whether taxes or spending are too high or whether municipal governments produce good value for taxpayers. -

Reduced Annualreport1972.Pdf

PROVINCE OF BRITISH COLUMBIA DEPARTMENT OF RECREATION AND CONSERVATION HON. ROBERT A. WILLIAMS, Minister LLOYD BROOKS, Deputy Minister REPORT OF THE Department of Recreation and Conservation containing the reports of the GENERAL ADMINISTRATION, FISH AND WILDLIFE BRANCH, PROVINCIAL PARKS BRANCH, BRITISH COLUMBIA PROVINCIAL MUSEUM, AND COMMERCIAL FISHERIES BRANCH Year Ended December 31 1972 Printed by K. M. MACDONALD, Printer to tbe Queen's Most Excellent Majesty in right of the Province of British Columbia. 1973 \ VICTORIA, B.C., February, 1973 To Colonel the Honourable JOHN R. NICHOLSON, P.C., O.B.E., Q.C., LLD., Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of British Columbia. MAY IT PLEASE YOUR HONOUR: Herewith I beg respectfully to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Recreation and Conservation for the year ended December 31, 1972. ROBERT A. WILLIAMS Minister of Recreation and Conservation 1_) VICTORIA, B.C., February, 1973 The Honourable Robert A. Williams, Minister of Recreation and Conservation. SIR: I have the honour to submit the Annual Report of the Department of Recreation and Conservation for the year ended December 31, 1972. LLOYD BROOKS Deputy Minister of Recreation and Conservation CONTENTS PAGE Introduction by the Deputy Minister of Recreation and Conservation_____________ 7 General Administration_________________________________________________ __ ___________ _____ 9 Fish and Wildlife Branch____________ ___________________ ________________________ _____________________ 13 Provincial Parks Branch________ ______________________________________________