Thickness of the Atmosphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Temperature As the Basis, the Atmosphere Is Divided Into Four Layers

Using temperature as the basis, the atmosphere is divided into four layers. The temperature decrease in the troposphere, the bottom layer in which we live, is called the "environmental lapse rate." Its average value is 6.5°C per kilometer, a figure known as the "normal lapse rate." A temperature "inversion," in which temperatures increase with height, is sometimes observed in shallow layers in the troposphere. The thickness of the troposphere is generally greater in the tropics than in polar regions. Essentially all important weather phenomena occur in the troposphere. Beyond the troposphere lies the stratosphere; the boundary between the troposphere and stratosphere is known as the tropopause. In the stratosphere, the temperature at first remains constant to a height of about 20 kilometers (12 miles) before it begins a sharp increase due to the absorption of ultraviolet radiation from the Sun by ozone. The temperatures continue to increase until the stratopause is encountered at a height of about 50 kilometers (30 miles).In the mesosphere, the third layer, temperatures again decrease with height until the mesopause, some 80 kilometers (50 miles) above the surface.The fourth layer, the thermosphere, with no well-defined upper limit, consists of extremely rarefied air. Temperatures here increase with an increase in altitude.Besides layers defined by vertical variations in temperature, the atmosphere is often divided into two layers based on composition. The homosphere (zone of homogeneous composition), from Earth’s surface to an altitude of about 80 kilometers (50 miles), consists of air that is uniform in terms of the proportions of its component gases. -

Apihelion Vs

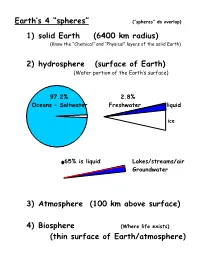

Earth’s 4 “spheres” (“spheres” do overlap) 1) solid Earth (6400 km radius) (Know the “Chemical” and “Physical” layers of the solid Earth) 2) hydrosphere (surface of Earth) (Water portion of the Earth’s surface) 97.2% 2.8% Oceans – Saltwater Freshwater liquid ice .65% is liquid Lakes/streams/air Groundwater 3) Atmosphere (100 km above surface) 4) Biosphere (Where life exists) (thin surface of Earth/atmosphere) Weather vs Climate constantly “average weather” changing 6 basic elements of weather/climate temperature of air humidity of air type & amount of cloudiness type & amount of precipitation pressure exerted by air speed & direction of wind Atmosphere Composition / Ozone Layer (pgs. 6-9) Evolution of Earth’s Atmosphere (pgs. 9-11) Exploring the Atmosphere time line for inventions/discoveries 1593 Galileo “thermometer” 1643 Torricelli barometer 1661 Boyle (P)(V)=constant 1752 Franklin kite -> lightning=electricity 1880(90) manned ballons 1900-today unmanned ballons using radiosondes = radio transmitters that send info on temperature/pressure/relative humidity today rockets & airplanes weather radar & satellites Height/Structure of Atmosphere Exosphere (above 800 km) 100 km 100 km (Ionosphere) 90 km Thermosphere 90 km 80 km 80 km 70 km 70 km 60 km Mesosphere 60 km 50 km 50 km 40 km (Ozone Layer) 40 km 30 km Stratosphere 30 km 20 km 20 km 10 km 10 km Troposphere 0 km 0 km extremely 0o hot really hot 0 100 500 1000 cold Temperature Pressure (mb) Homosphere vs Heterosphere 0-80 km above 80 km uniform distribution varies by mass of molecule N2 O He H Ionosphere located in the Thermosphere/Heterosphere N2 O ionize due to absorbing high-energy solar energy lose electrons and become +charged ions electrons are free to move Solar flares let go of lots of solar energy (charged particles) The charged particles mix with Earth’s magnetic field Charged particles are guided toward N-S magnetic poles Charged particles mix with ionosphere and cause Auroras Electromagnetic Spectrum Seasons are due to angle of sun’s rays. -

The Effects of the Atmosphere and Weather on Radio Astronomy Observations

The Effects of the Atmosphere and Weather on Radio Astronomy Observations Ronald J Maddalena July 2011 The Influence of the Atmosphere and Weather at cm- and mm-wavelengths Opacity Cloud Cover Calibration Continuum performance System performance – Tsys Calibration Observing techniques Winds Hardware design Pointing Refraction Safety Pointing Telescope Scheduling Air Mass Proportion of proposals Calibration that should be accepted Interferometer & VLB phase Telescope productivity errors Aperture phase errors Structure of the Lower Atmosphere Refraction Refraction Index of Refraction is weather dependent: .3 73×105 ⋅ P (mBar) 6 77 6. ⋅ PTotal (mBar) H 2O (n0 − )1 ⋅10 ≈ + +... T(C) + 273.15 ()T(C) + 273.15 2 P (mBar) ≈ 6.112⋅ea H 2O .7 62⋅TDewPt (C) where a ≈ 243.12 +TDewPt (C) Froome & Essen, 1969 http://cires.colorado.edu/~voemel/vp.html Guide to Meteorological Instruments and Methods of Observation (CIMO Guide) (WMO, 2008) Refraction For plane-parallel approximation: n0 • Cos(Elev Obs )=Cos(Elev True ) R = Elev Obs – Elev True = (n 0-1) • Cot(Elev Obs ) Good to above 30 ° only For spherical Earth: n 0 dn() h Elev− Elev = a ⋅ n ⋅cos( Elev ) ⋅ Obs True0 Obs 2 2 2 2 2 ∫1 nh()(⋅ ah + )() ⋅ nh − an ⋅0 ⋅ cos( Elev Obs ) a = Earth radius; h = distance above sea level of atmospheric layer, n(h) = index of refraction at height h; n 0 = ground-level index of refraction See, for example, Smart, “Spherical Astronomy” Refraction Important for good pointing when combining: large aperture telescopes at high frequencies at low elevations (i.e., the GBT) Every observatory handles refraction differently. Offset pointing helps eliminates refraction errors Since n(h) isn’t usually known, most (all?) observatories use some simplifying model. -

Air Mass Effect on the Performance of Organic Solar Cells

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Energy Procedia 36 ( 2013 ) 714 – 721 TerraGreen 13 International Conference 2013 - Advancements in Renewable Energy and Clean Environment Air mass effect on the performance of organic solar cells A. Guechi1*, M. Chegaar2 and M. Aillerie3,4, # 1Institute of Optics and Precision Mechanics, Ferhat Abbas University, 19000, Setif, Algeria 2L.O.C, Department of Physics, Faculty of Sciences, Ferhat Abbas University, 19000, Setif, Algeria Email : [email protected], [email protected] 3Lorraine University, LMOPS-EA 4423, 57070 Metz, France 4Supelec, LMOPS, 57070 Metz, France #Email: [email protected] Abstract The objective of this study is to evaluate the effect of variations in global and diffuse solar spectral distribution due to the variation of air mass on the performance of two types of solar cells, DPB (etraphenyl–dibenzo–periflanthene) and CuPc (Copper-Phthalocyanine) using the spectral irradiance model for clear skies, SMARTS2, over typical rural environment in Setif. Air mass can reduce the sunlight reaching a solar cell and thereby cause a reduction in the electrical current, fill factor, open circuit voltage and efficiency. The results indicate that this atmospheric parameter causes different effects on the electrical current produced by DPB and CuPc solar cells. In addition, air mass reduces the current of the DPB and CuPc cells by 82.34% and 83.07 % respectively under global radiation. However these reductions are 37.85 % and 38.06%, for DPB and CuPc cells respectively under diffuse solar radiation. The efficiency decreases with increasing air mass for both DPB and CuPc solar cells. © 20132013 The The Authors. -

Atmospheric Gases and Air Quality

12.3SECTION Atmospheric Gases and Air Quality Key Terms + Exosphere H H criteria air contaminants 500 He- He Ionosphere O Thermosphere 1 1 1 O 1NO 1OZ 1 2 1 1 Heterosphere NZ 1O 90 Photoionization N2 O2 10-5 70 Mesosphere CO 2 Pressure (mmHg) Pressure -3 of O Photodissociation Figure 12.10 Variations in 10 50 (km)Altitude 78% N2 pressure, temperature, and 21% O CO2 O2 Stratosphere 2 the components that make 1% Ar. etc. Ozone layer up Earth’s atmosphere are 30 Homosphere summarized here. 10-1 Infer How can you explain the changes in temperature Troposphere 10 of O Photodissociation H2O with altitude? 1 150 273 300 2000 major major major components components components Temperature (˚C) Figure 12.10 summarizes information about the structure and composition of Earth’s atmosphere. Much of this information is familiar to you from earlier in this unit or from your study of science or geography in earlier grades. As you know from Boyle’s law, gases are compressible. Th us, pressure in the atmosphere decreases with altitude, and this decrease is more rapid at lower altitudes than at higher altitudes. In fact, the vast majority of the mass of the atmosphere—about 99 percent—lies within 30 km of Earth’s surface. About 90 percent of the mass of the atmosphere lies within 15 km of the surface, and about 75 percent lies within 11 km. Th e atmosphere is divided into fi ve distinct regions, based on temperature changes. You may recognize the names of some or perhaps all of these regions: the troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere, and exosphere. -

Nighttime Photochemical Model and Night Airglow on Venus

Planetary and Space Science 85 (2013) 78–88 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Planetary and Space Science journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pss Nighttime photochemical model and night airglow on Venus Vladimir A. Krasnopolsky n a Department of Physics, Catholic University of America, Washington, DC 20064, USA b Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudnyy 141700 Russia article info abstract Article history: The photochemical model for the Venus nighttime atmosphere and night airglow (Krasnopolsky, 2010, Received 23 December 2012 Icarus 207, 17–27) has been revised to account for the SPICAV detection of the nighttime ozone layer and Received in revised form more detailed spectroscopy and morphology of the OH nightglow. Nighttime chemistry on Venus is 28 April 2013 induced by fluxes of O, N, H, and Cl with mean hemispheric values of 3 Â 1012,1.2Â 109,1010, and Accepted 31 May 2013 − − 1010 cm 2 s 1, respectively. These fluxes are proportional to column abundances of these species in the Available online 18 June 2013 daytime atmosphere above 90 km, and this favors their validity. The model includes 86 reactions of 29 Keywords: species. The calculated abundances of Cl2, ClO, and ClNO3 exceed a ppb level at 80–90 km, and Venus perspectives of their detection are briefly discussed. Properties of the ozone layer in the model agree Photochemistry with those observed by SPICAV. An alternative model without the flux of Cl agrees with the observed O Night airglow 3 peak altitude and density but predicts an increase of ozone to 4 Â 108 cm−3 at 80 km. -

Elemental Geosystems, 5E (Christopherson) Chapter 2 Solar Energy, Seasons, and the Atmosphere

Elemental Geosystems, 5e (Christopherson) Chapter 2 Solar Energy, Seasons, and the Atmosphere 1) Our planet and our lives are powered by A) energy derived from inside Earth. B) radiant energy from the Sun. C) utilities and oil companies. D) shorter wavelengths of gamma rays, X-rays, and ultraviolet. Answer: B 2) Which of the following is true? A) The Sun is the largest star in the Milky Way Galaxy. B) The Milky Way is part of our Solar System. C) The Sun produces energy through fusion processes. D) The Sun is also a planet. Answer: C 3) Which of the following is true about the Milky Way galaxy in which we live? A) It is a spiral-shaped galaxy. B) It is one of millions of galaxies in the universe. C) It contains approximately 400 billion stars. D) All of the above are true. E) Only A and B are true. Answer: D 4) The planetesimal hypothesis pertains to the formation of the A) universe. B) galaxy. C) planets. D) ocean basins. Answer: C 5) The flattened structure of the Milky Way is revealed by A) the constellations of the Zodiac. B) a narrow band of hazy light that stretches across the night sky. C) the alignment of the planets in the solar system. D) the plane of the ecliptic. Answer: B 6) Earth and the Sun formed specifically from A) the galaxy. B) unknown origins. C) a nebula of dust and gases. D) other planets. Answer: C 7) Which of the following is not true of stars? A) They form in great clouds of gas and dust known as nebula. -

Lecture.1.Introduction.Pdf

Lecture 1: Introduction to the Climate System Earth’s Climate System Solar forcing T mass (& radiation) The ultimate driving T & mass relation in vertical mass (& energy, weather..) Atmosphere force to Earth’s climate system is the heating from Energy T vertical stability vertical motion thunderstorm the Sun. Ocean Land The solar energy drives What are included in Earth’s climate system? Solid Earth three major cycles (energy, water, and biogeochemisty) What are the general properties of the Atmosphere? Energy, Water, and in the climate system. How about the ocean, cryosphere, and land surface? Biogeochemistry Cycles ESS200 ESS200 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Thickness of the Atmosphere (from Meteorology Today) The thickness of the atmosphere is only about 2% 90% of Earth’s thickness (Earth’s 70% radius = ~6400km). Most of the atmospheric mass is confined in the lowest 100 km above the sea level. tmosphere Because of the shallowness of the atmosphere, its motions over large A areas are primarily horizontal. Typically, horizontal wind speeds are a thousands time greater than vertical wind speeds. (But the small vertical displacements of air have an important impact on ESS200 the state of the atmosphere.) ESS200 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Prof. Jin-Yi Yu 1 Vertical Structure of the Atmosphere Composition of the Atmosphere (inside the DRY homosphere) composition temperature electricity Water vapor (0-0.25%) 80km (from Meteorology Today) ESS200 (from The Blue Planet) ESS200 Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Prof. Jin-Yi Yu Origins of the Atmosphere What Happened to H2O? When the Earth was formed 4.6 billion years ago, Earth’s atmosphere was probably mostly hydrogen (H) and helium (He) plus hydrogen The atmosphere can only hold small fraction of the mass of compounds, such as methane (CH4) and ammonia (NH3). -

Evidence of the Complexity of Aerosol Transport in the Lower Troposphere on the Namibian Coast During AEROCLO-Sa

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 19, 14979–15005, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19-14979-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Evidence of the complexity of aerosol transport in the lower troposphere on the Namibian coast during AEROCLO-sA Patrick Chazette1, Cyrille Flamant2, Julien Totems1, Marco Gaetani2,3, Gwendoline Smith1,3, Alexandre Baron1, Xavier Landsheere3, Karine Desboeufs3, Jean-François Doussin3, and Paola Formenti3 1Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement (LSCE), Laboratoire mixte CEA-CNRS-UVSQ, UMR CNRS 1572, CEA Saclay, 91191 Gif-sur-Yvette, France 2LATMOS/IPSL, Sorbonne Université, CNRS, UVSQ, Paris, France 3Laboratoire Interuniversitaire des Systèmes Atmosphériques (LISA) UMR CNRS 7583, Université Paris-Est-Créteil, Université de Paris, Institut Pierre Simon Laplace, Créteil, France Correspondence: Patrick Chazette ([email protected]) Received: 29 May 2019 – Discussion started: 3 June 2019 Revised: 27 October 2019 – Accepted: 28 October 2019 – Published: 11 December 2019 Abstract. The evolution of the vertical distribution and opti- ern Africa by the equatorward moving cut-off low originat- cal properties of aerosols in the free troposphere, above stra- ing from within the westerlies. All the observations show a tocumulus, is characterized for the first time over the Namib- very complex mixture of aerosols over the coastal regions of ian coast, a region where uncertainties on aerosol–cloud cou- Namibia that must be taken into account when investigating pling in climate simulations are significant. We show the high aerosol radiative effects above stratocumulus clouds in the variability of atmospheric aerosol composition in the lower southeast Atlantic Ocean. -

Ionospheric Reflections and Weather Forecasting for Eastern China*

Ionospheric Reflections and Weather Forecasting for Eastern China* REV. E. GHERZI, S.J. Director for Meteorology and Seismology, Zi Ka Wei Observatory, Shanghai, China HE FOLLOWING LINES describe some Another detail of our technique was that T very interesting and practical results we reduced to 20 watts or less the power obtained at the Zi Ka Wei Observa- radiated by our Hertz aerial, in order to get tory during the past five years, by means of reflections only from a well-ionized layer. the usual ionospheric radio soundings which This frequency of 6000 kc was used con- give the heights of the well-known E and F stantly during all these five years of research, layers. As early as 1936, Martin and Pulley and as we had at our disposal a file of (of the Radio Research Board, Melbourne) synoptic maps from our weather service, we reported on a "Correlation of conditions in quickly noticed a very interesting coincidence the ionosphere with barometric pressure at between the presence of an E or an F, or an the ground.,M We thought this idea very F2 echo, and the air mass which was "domi- interesting and started research along that nating the weather"! Namely, we found line. We wanted to find out if the motions that: (1) every time the Pacific trade-wind of the different air masses which produce air mass which was causing the weather, we the weather of our regions could be corre- had the E-layer reflection; (2) every time lated with the results obtained by the usual the Siberian air mass was dominating the ionospheric sounding technique. -

Lecture 1 Lecture 1 Outline of Today's Lecture Science Scientific Method

Lecture 1 Lecture 1 Outline of Today’s Lecture • What is it that defines science? • What is meteorology? • A brief history of meteorology. • What does the atmosphere do for us? • What is the atmosphere composed of? • Intro to atmospheric structure 1 2 Science Scientific Method • What is it that defines science? 1. Start with an educated guess or “hypothesis” 2. The guess should leads to a prediction that can • How is science distinguished from be tested. other academic endeavors (e.g, history 3. Design an experiment to test the hypothesis and or comparative religion)? prediction. 4. Evaluate the results of the experiment to verify or • Why is creationism not considered refute hypothesis science by scientists? 5. Construct a theory (or model) based on test results. 6. Repeat cycle (1-5) to refine/modify the theory. 3 4 Scientific Method What is Meteorology? • Our understanding of the world grows as our theories become more complete and precise. • The term meteorology comes from the Greek • A key to the Scientific Method is that the results of a word meteoros, meaning, “high in the air.” good experiment are reproducible. The same • Rain and snow are hydrometeors. experiment using the same hardware will produce the same results time after time. • Meteorology is the study of the atmosphere • If a hypothesis can not be tested then it falls outside the and the processes that produce weather. current realm of scientific understanding or knowledge, • Meteorology is also called atmospheric and is considered “speculation.” science. 5 6 A Brief History of Meteorology A Brief History of Meteorology 340 BC In a book he called Meteorologica, the Greek Answer: Lack of instruments to make observations. -

PHAK Chapter 12 Weather Theory

Chapter 12 Weather Theory Introduction Weather is an important factor that influences aircraft performance and flying safety. It is the state of the atmosphere at a given time and place with respect to variables, such as temperature (heat or cold), moisture (wetness or dryness), wind velocity (calm or storm), visibility (clearness or cloudiness), and barometric pressure (high or low). The term “weather” can also apply to adverse or destructive atmospheric conditions, such as high winds. This chapter explains basic weather theory and offers pilots background knowledge of weather principles. It is designed to help them gain a good understanding of how weather affects daily flying activities. Understanding the theories behind weather helps a pilot make sound weather decisions based on the reports and forecasts obtained from a Flight Service Station (FSS) weather specialist and other aviation weather services. Be it a local flight or a long cross-country flight, decisions based on weather can dramatically affect the safety of the flight. 12-1 Atmosphere The atmosphere is a blanket of air made up of a mixture of 1% gases that surrounds the Earth and reaches almost 350 miles from the surface of the Earth. This mixture is in constant motion. If the atmosphere were visible, it might look like 2211%% an ocean with swirls and eddies, rising and falling air, and Oxygen waves that travel for great distances. Life on Earth is supported by the atmosphere, solar energy, 77 and the planet’s magnetic fields. The atmosphere absorbs 88%% energy from the sun, recycles water and other chemicals, and Nitrogen works with the electrical and magnetic forces to provide a moderate climate.