Oscar Roundtable: the Composers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vliv Artificiální a Nonartificiální Hudby Na Hudbu Filmovou (Sociologicko-Psychologická Sonda Do Recepce Filmové Hudby)

Masarykova univerzita Filozofická fakulta Ústav hudební vědy Hudební věda Martin Polák Vliv artificiální a nonartificiální hudby na hudbu filmovou (sociologicko-psychologická sonda do recepce filmové hudby) Bakalářská diplomová práce Vedoucí práce: Doc. PhDr. Mikuláš Bek, Ph.D. Brno 2010 Prohlašuji, ţe jsem diplomovou bakalářskou práci vypracoval samostatně a pouze s vyuţitím uvedených pramenů a literatury. ……………………………….. 2 Děkuji doc. PhDr. Mikuláši Bekovi Ph.D., za cenné rady při koncepci diplomové práce a výzkumu. Dále bych chtěl poděkovat Mgr. Viktoru Pantůčkovi za koncepčně pestré návrhy výzkumných destinací. Z hlediska motivační podpory a konzultační spolupráce bych rád poděkoval prof. Eeru Tarastimu, Ph.D.; prof. Erkki Pekkilovi, Ph.D a prof. Philipu Taggovi za poskytnuté materiály. V neposlední řadě bych chtěl poděkovat Mgr. arch. Stanislavu Grichovi za inspirační podporu při tvorbě výzkumné práce. Zároveň děkuji Bc. Magdaleně Pečtové za jazykovou korekturu. Zejména však děkuji všem respondentům, kteří se zúčastnili výzkumné části projektu. 3 Obsah: 1 Úvod: ..................................................................................................................................6 2 Filmová hudba .....................................................................................................................8 2.1 Typologie filmové hudby ..................................................................................................9 2.1.A Archivní hudba .......................................................................................................... -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

Listening to Movies: Film Music and the American Composer Charles Elliston Long Middle School INTRODUCTION I Entered College

Listening to Movies: Film Music and the American Composer Charles Elliston Long Middle School INTRODUCTION I entered college a naïve 18-year-old musician. I had played guitar for roughly four years and was determined to be the next great Texas blues guitarist. However, I was now in college and taking the standard freshman music literature class. Up to this point the most I knew about music other than rock or blues was that Beethoven was deaf, Mozart composed as a child, and Chopin wrote a really cool piano sonata in B-flat minor. So, we’re sitting in class learning about Berlioz, and all of the sudden it occurred to me: are there any composers still working today? So I risked looking silly and raised my hand to ask my professor if there were composers that were still working today. His response was, “Of course!” In discussing modern composers, the one medium that continuously came up in my literature class was that of film music. It occurred to me then that I knew a lot of modern orchestral music, even though I didn’t really know it. From the time when I was a little kid, I knew the name of John Williams. Some of my earliest memories involved seeing such movies as E.T., Raiders of the Lost Ark, and The Empire Strikes Back. My father was a musician, so I always noted the music credit in the opening credits. All of those films had the same composer, John Williams. Of course, I was only eight years old at the time, so in my mind I thought that John Williams wrote all the music for the movies. -

BBC Four Programme Information

SOUND OF CINEMA: THE MUSIC THAT MADE THE MOVIES BBC Four Programme Information Neil Brand presenter and composer said, “It's so fantastic that the BBC, the biggest producer of music content, is showing how music works for films this autumn with Sound of Cinema. Film scores demand an extraordinary degree of both musicianship and dramatic understanding on the part of their composers. Whilst creating potent, original music to synchronise exactly with the images, composers are also making that music as discreet, accessible and communicative as possible, so that it can speak to each and every one of us. Film music demands the highest standards of its composers, the insight to 'see' what is needed and come up with something new and original. With my series and the other content across the BBC’s Sound of Cinema season I hope that people will hear more in their movies than they ever thought possible.” Part 1: The Big Score In the first episode of a new series celebrating film music for BBC Four as part of a wider Sound of Cinema Season on the BBC, Neil Brand explores how the classic orchestral film score emerged and why it’s still going strong today. Neil begins by analysing John Barry's title music for the 1965 thriller The Ipcress File. Demonstrating how Barry incorporated the sounds of east European instruments and even a coffee grinder to capture a down at heel Cold War feel, Neil highlights how a great composer can add a whole new dimension to film. Music has been inextricably linked with cinema even since the days of the "silent era", when movie houses employed accompanists ranging from pianists to small orchestras. -

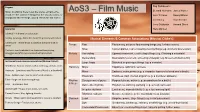

Knowledge Organiser

Key Composers Purpose Bernard Hermann James Horner Music in a film is there to set the scene, enhance the AoS3 – Film Music mood, tell the audience things that the visuals cannot, or John Williams Danny Elfman manipulate their feelings. Sound effects are not music! John Barry Alan Silvestri Jerry Goldsmith Howard Shore Key terms Hans Zimmer Leitmotif – A theme for a character Mickey-mousing – When the music fits precisely with action Musical Elements & Common Associations (Musical Cliche’s) Underscore – where music is played at the same time as action Tempo Fast Excitement, action or fast-moving things (eg. A chase scene) Slow Contemplation, rest or slowing-moving things (eg. A funeral procession) Fanfare – short melodies from brass sections playing arpeggios and often accompanied with percussion Melody Ascending Upward movement, or a feeling of hope (eg. Climbing a mountain) Descending Downward movement, or feeling of despair (eg. Movement down a hill) Instruments and common associations (Musical Clichés) Large leaps Distorted or grotesque things (eg. a monster) Woodwind - Natural sounds such as bird song, animals, rivers Harmony Major Happiness, optimism, success Bassoons – Sometimes used for comic effect (i.e. a drunkard) Minor Sadness, seriousness (e.g. a character learns of a loved one’s death) Brass - Soldiers, war, royalty, ceremonial occasions Dissonant Scariness, pain, mental anguish (e.g. a murderer appears) Tuba – Large and slow moving things Rhythm Strong sense of pulse Purposefulness, action (e.g. preparations for a battle) & Metre Harp – Tenderness, love Dance-like rhythms Playfulness, dancing, partying (e.g. a medieval feast) Glockenspiel – Magic, music boxes, fairy tales Irregular rhythms Excitement, unpredictability (e.g. -

Musikliste Zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel Sortiert in Der Reihenfolge, in Der Sie in Der Doku Zu Hören Sind

Z Musikliste zu Terra X „Unsere Wälder“ Titel sortiert in der Reihenfolge, in der sie in der Doku zu hören sind. Folge 1 MUSIK - Titel CD / Interpret Composer Trailer Terra X Trailer Terra X Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Dr. Ford Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Ramin Djawadi Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Eleven Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Race To Mark's Flat Bridget Jones's Baby / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Boggis, Bunce and Fantastic Mr. Fox / Alexandre Desplat Alexandre Desplat Bean Hibernation Pod 1625 Passengers / Thomas Newman Thomas Newman Jack It Up Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Letters Theodore Shapiro Reporters Swarm Confirmation / Harry Gregson Williams Harry Gregson Williams Persistence Burnt / Rob Simonsen Rob Simonsen Introducing Howard Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Inlet Theodore Shapiro The Dream and the Collateral Beauty / Theodore Shapiro Theodore Shapiro Letters Main Title Theme – Westworld - Season 1 / Ramin Djawadi Westworld Ramin Djawadi Fell Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers Me Before You Me Before You / Craig Armstrong Craig Armstrong Orchestral This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon The Skylab Plan Steve Jobs / Daniel Pemberton Daniel Pemberton Photos in the Woods Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon Speight Lived Here The Knick (Season 2) / Cliff Martinez Cliff Martinez This Isn't You Stranger Things Vol. 1 / Kyle Dixon Kyle Dixon 3 Minutes Of Moderat A New Beginning Captain Fantastic / Alex Somers Alex Somers 3 Minutes Of Moderat The Walk The Walk / Alan Silvestri Alan Silvestri Dr. -

4BH 1000 Best Songs 2011 Prez Final

The 882 4BH1000BestSongsOfAlltimeCountdown(2011) Number Title Artist 1000 TakeALetterMaria RBGreaves 999 It'sMyParty LesleyGore 998 I'llNeverFallInLoveAgain BobbieGentry 997 HeavenKnows RickPrice 996 ISayALittlePrayer ArethaFranklin 995 IWannaWakeUpWithYou BorisGardiner 994 NiceToBeWithYou Gallery 993 Pasadena JohnPaulYoung 992 IfIWereACarpenter FourTops 991 CouldYouEverLoveMeAgain Gary&Dave 990 Classic AdrianGurvitz 989 ICanDreamAboutYou DanHartman 988 DifferentDrum StonePoneys/LindaRonstadt 987 ItNeverRainsInSouthernCalifornia AlbertHammond 986 Moviestar Harpo 985 BornToTry DeltaGoodrem 984 Rockin'Robin Henchmen 983 IJustWantToBeYourEverything AndyGibb 982 SpiritInTheSky NormanGreenbaum 981 WeDoIt R&JStone 980 DriftAway DobieGray 979 OrinocoFlow Enya 978 She'sLikeTheWind PatrickSwayze 977 GimmeLittleSign BrentonWood 976 ForYourEyesOnly SheenaEaston 975 WordsAreNotEnough JonEnglish 974 Perfect FairgroundAttraction 973 I'veNeverBeenToMe Charlene 972 ByeByeLove EverlyBrothers 971 YearOfTheCat AlStewart 970 IfICan'tHaveYou YvonneElliman 969 KnockOnWood AmiiStewart 968 Don'tPullYourLove Hamilton,JoeFrank&Reynolds 967 You'veGotYourTroubles Fortunes 966 Romeo'sTune SteveForbert 965 Blowin'InTheWind PeterPaul&Mary 964 Zoom FatLarry'sBand 963 TheTwist ChubbyChecker 962 KissYouAllOver Exile 961 MiracleOfLove Eurythmics 960 SongForGuy EltonJohn 959 LilyWasHere DavidAStewart/CandyDulfer 958 HoldMeClose DavidEssex 957 LadyWhat'sYourName Swanee 956 ForeverAutumn JustinHayward 955 LottaLove NicoletteLarson 954 Celebration Kool&TheGang 953 UpWhereWeBelong -

A Study of Musical Affect in Howard Shore's Soundtrack to Lord of the Rings

PROJECTING TOLKIEN'S MUSICAL WORLDS: A STUDY OF MUSICAL AFFECT IN HOWARD SHORE'S SOUNDTRACK TO LORD OF THE RINGS Matthew David Young A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC IN MUSIC THEORY May 2007 Committee: Per F. Broman, Advisor Nora A. Engebretsen © 2007 Matthew David Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Per F. Broman, Advisor In their book Ten Little Title Tunes: Towards a Musicology of the Mass Media, Philip Tagg and Bob Clarida build on Tagg’s previous efforts to define the musical affect of popular music. By breaking down a musical example into minimal units of musical meaning (called musemes), and comparing those units to other musical examples possessing sociomusical connotations, Tagg demonstrated a transfer of musical affect from the music possessing sociomusical connotations to the object of analysis. While Tagg’s studies have focused mostly on television music, this document expands his techniques in an attempt to analyze the musical affect of Howard Shore’s score to Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy. This thesis studies the ability of Shore’s film score not only to accompany the events occurring on-screen, but also to provide the audience with cultural and emotional information pertinent to character and story development. After a brief discussion of J.R.R. Tolkien’s description of the cultures, poetry, and music traits of the inhabitants found in Middle-earth, this document dissects the thematic material of Shore’s film score. -

EMR 12366 the Cider House Rules

The Cider House Rules L’oeuvre de Dieu, la part du Diable / Gottes Werk & Teufels Beitrag The Cider House / The Ocean / Picker Leave / End Credits Wind Band / Concert Band / Harmonie / Blasorchester Arr.: Jirka Kadlec Rachel Portman EMR 12366 st 1 Score 2 1 Trombone + st nd 4 1 Flute 2 2 Trombone + nd 4 2 Flute / Piccolo 1 Bass Trombone + 1 Oboe (optional) 2 Baritone + 1 Bassoon (optional) 2 E Bass 1 E Clarinet (optional) 2 B Bass st 5 1 B Clarinet 1 Tuba 4 2nd B Clarinet 1 String Bass (optional) 4 3rd B Clarinet 1 Timpani 1 B Bass Clarinet (optional) 1 1st Percussion (Glockenspiel / Xylophone) 1 B Soprano Saxophone (optional) 1 2nd Percussion (Suspended Cymbal / Claves) 2 1st E Alto Saxophone 1 Drum Set 2 2nd E Alto Saxophone 2 B Tenor Saxophone Special Parts Fanfare Parts 1 E Baritone Saxophone (optional) st 1 1st B Trombone 2 1 Flugelhorn 1 E Trumpet / Cornet (optional) nd nd 2 2 Flugelhorn st 1 2 B Trombone 2 1 B Trumpet / Cornet rd 1 B Bass Trombone 2 3 Flugelhorn 2 2nd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 B Baritone 2 3rd B Trumpet / Cornet 1 E Tuba 2 1st F & E Horn 1 B Tuba 2 2nd F & E Horn 2 3rd F & E Horn Print & Listen Drucken & Anhören Imprimer & Ecouter ≤ www.reift.ch Route du Golf 150 CH-3963 Crans-Montana (Switzerland) Tel. +41 (0) 27 483 12 00 Fax +41 (0) 27 483 42 43 E-Mail : [email protected] www.reift.ch Recorded on CD - Auf CD aufgenommen - Enregistré sur CD | Photocopying The Cider House Rules is illegal! L'oeuvre de Dieu, la part du Diable / Gottes Werk & Teufels Beitrag The Cider House / The Ocean / Picker Leave / End Credits Rachel Portman Arr.: Jirka Kadlec THE CIDER HOUSE 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 q = 100 1st Flute mp mf mp mp mf Fl. -

Film Music Week 4 20Th Century Idioms - Jazz

Film Music Week 4 20th Century Idioms - Jazz alternative approaches to the romantic orchestra in 1950s (US & France) – with a special focus on jazz... 1950s It was not until the early 50’s that HW film scores solidly move into the 20th century (idiom). Alex North (influenced by : Bartok, Stravinsky) and Leonard Rosenman (influenced by: Schoenberg, and later, Ligeti) are important influences here. Also of note are Georges Antheil (The Plainsman, 1937) and David Raksin (Force of Evil, 1948). Prendergast suggests that in the 30’s & 40’s the films possessed somewhat operatic or unreal plots that didn’t lend themselves to dissonance or expressionistic ideas. As Hollywood moved towards more realistic portrayals, this music became more appropriate. Alex North, leader in a sparser style (as opposed to Korngold, Steiner, Newman) scored Death of a Salesman (image above)for Elia Kazan on Broadway – this led to North writing the Streetcar film score for Kazan. European influences Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). • Director Frederico Fellini &composer Nino Rota (many examples) • Director François Truffault & composerGeorges Delerue, • Composer Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the • Professionals, 1966, Composer- Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). (continued) Also Hollywood was beginning to be strongly influenced by European films which has much more adventuresome scores or (often) no scores at all. Fellini & Rota, Truffault & Georges Delerue, Maurice Jarre (Sundays & Cybele, 1962) and later the Professionals, 1966, Ennio Morricone (Serge Leone, jazz background). -

Wmc Investigation: 10-Year Analysis of Gender & Oscar

WMC INVESTIGATION: 10-YEAR ANALYSIS OF GENDER & OSCAR NOMINATIONS womensmediacenter.com @womensmediacntr WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER ABOUT THE WOMEN’S MEDIA CENTER In 2005, Jane Fonda, Robin Morgan, and Gloria Steinem founded the Women’s Media Center (WMC), a progressive, nonpartisan, nonproft organization endeav- oring to raise the visibility, viability, and decision-making power of women and girls in media and thereby ensuring that their stories get told and their voices are heard. To reach those necessary goals, we strategically use an array of interconnected channels and platforms to transform not only the media landscape but also a cul- ture in which women’s and girls’ voices, stories, experiences, and images are nei- ther suffciently amplifed nor placed on par with the voices, stories, experiences, and images of men and boys. Our strategic tools include monitoring the media; commissioning and conducting research; and undertaking other special initiatives to spotlight gender and racial bias in news coverage, entertainment flm and television, social media, and other key sectors. Our publications include the book “Unspinning the Spin: The Women’s Media Center Guide to Fair and Accurate Language”; “The Women’s Media Center’s Media Guide to Gender Neutral Coverage of Women Candidates + Politicians”; “The Women’s Media Center Media Guide to Covering Reproductive Issues”; “WMC Media Watch: The Gender Gap in Coverage of Reproductive Issues”; “Writing Rape: How U.S. Media Cover Campus Rape and Sexual Assault”; “WMC Investigation: 10-Year Review of Gender & Emmy Nominations”; and the Women’s Media Center’s annual WMC Status of Women in the U.S.