Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Korunes Duke 0066D 14983.Pdf

How Linkage Disequilibrium and Recombination Shape Genetic Variation Within and Between Species by Katharine L Korunes University Program in Genetics and Genomics Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Mohamed Noor, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Rausher, Chair ___________________________ Paul Magwene ___________________________ John Willis ___________________________ Jeff Sekelsky Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Genetics and Genomics in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT How Linkage Disequilibrium and Recombination Shape Genetic Variation Within and Between Species by Katharine L Korunes University Program in Genetics and Genomics Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Mohamed Noor, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Rausher, Chair ___________________________ Paul Magwene ___________________________ John Willis ___________________________ Jeff Sekelsky An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Genetics and Genomics in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Katharine L Korunes 2019 Abstract Meiotic recombination creates genetic diversity by shuffling combinations of alleles across loci, yet alleles at neighboring loci often remain non-randomly associated. This non-random association is -

Book Review: Jerry A. Coyne's Why Evolution Is True

A peer-reviewed electronic journal published by the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies ISSN 1541-0099 20(1) – June 2009 Book review: Jerry A. Coyne’s Why Evolution Is True Russell Blackford, Monash University Editor-in-Chief, Journal of Evolution and Technology Journal of Evolution and Technology - Vol. 20 Issue 1 – June 2009 - pgs 61-66 http://jetpress.org/v20/blackford.htm Why Evolution Is True. By Jerry A. Coyne. Viking, New York, 2009. 282 pp., $27.95 (hardback). ISBN: 978 0 670 02053 9 (all page references to this edition) Jerry A. Coyne is a professor at the University of Chicago, where his research focuses on evolutionary genetics and speciation. In Why Evolution Is True, he presents a full-scale defence of modern evolutionary theory, which can, so he notes, be described in one long sentence: Life on earth evolved gradually beginning with one primitive species – perhaps a self-replicating molecule – that lived more than 3.5 billion years ago; it then branched out over time, throwing off many new and diverse species; and the mechanism for most (but not all) of evolutionary change is natural selection. (3.) This breaks down into six components: the fact of evolution, in the sense of genetic change over time; the idea of gradualism, of changes taking place over many generations (although sometimes they come about relatively quickly, depending on the evolutionary pressures operating); the phenomenon of speciation, whereby new species split off from existing lineages; the common ancestry of different species, since new species, -

Evolution Is a Short-Order Cook, Not a Watchmaker

NATURE|Vol 435|19 May 2005 CORRESPONDENCE When science meets religion in the classroom SIR – In the Editorial “Dealing with design” such a reconciliation impossible because faith scientific challenges to their faith should seek (Nature434,1053; 2005), Natureclaims that and science are two mutually exclusive ways guidance from a theologian, not a scientist. scientists have not dealt effectively with the of looking at the world. For such scientists, Scientists should never have to apologize for threat to evolutionary biology posed by Natureapparently prescribes hypocrisy. The teaching science. ‘intelligent design’ (ID) creationism. Rather real business of science teachers is to teach Jerry Coyne than ignoring, dismissing or attacking ID, science, not to help students shore up world- Department of Ecology and Evolution, University scientists should, the editors suggest, learn views that crumble when they learn science. of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 60637, USA how religious people can come to terms And ID creationism is not science, despite Peter AtkinsLincoln College, University of Oxford with science, and teach these methods of the editors’ suggestion that ID “tries to use Colin BlakemoreMedical Research Council, London accommodation in the classroom. The goal scientific methods to find evidence of God in Richard DawkinsOxford University Museum, University of Oxford of science education should thus be “to point nature”. Rather, advocates of ID pretend to use Steve JonesGalton Laboratories, University College London to options other than ID for reconciling scientific methods to support their religious Richard LewontinMuseum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University science and belief ”. In this way, students’ faith preconceptions. It has no more place in the John Maddox 9 Pitt Street, London W8 4NX will not be challenged by scientific truth, and biology classroom than geocentrism has in Paul NurseThe Rockefeller University, New York evolution will triumph. -

GSA Welcomes 2012 Board Members

7INTERs3PRING 4HE'3!2EPORTER winter s spring 2012 New Executive GSA Welcomes 2012 Board Members Director Now on Board The Genetics Society of America New Members of the GSA Board of welcomes four new members elected Directors Adam P. Fagen, by the general membership to the Ph.D., stepped in as 2012 GSA Board of Directors. The VICE PRESIDENT: GSA’s new Executive new members are: Michael Lynch Michael Lynch, Director beginning (Indiana University), who serves as Distinguished December 1, 2011. vice president in 2012 and as GSA Professor of Dr. Fagen previously president in 2013 and Marnie E. Biology, Class of was at the American Halpern (Carnegie Institution for 1954 Professor, Society of Plant Science); Mohamed Noor (Duke Department of Biologists (ASPB), University); and John Schimenti Biology, Indiana where he was the director of public (Cornell University), who will serve as University, continued on page nineteen directors. Bloomington. Dr. Lynch is a population and evolutionary biologist and a In addition to these elected officers, long-time member of GSA. Dr. Lynch 2012 Brenda J. Andrews (University of sees GSA as the home for geneticists Toronto), Editor-in-Chief of GSA’s who study a broad base of topics GSA Award journal, G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics, and organisms, and as a forum Recipients which was first published online in where general discussion occurs, June 2011, becomes a member of the whether based on the principles Announced Board of Directors. The bylaws have of genetics, the most pressing historically included the GENETICS GSA is pleased to announce the issues within the discipline itself, or editor-in-chief on the Board and as a responses to societal concerns and/ 2012 recipients of its five awards result of a 2011 bylaw revision, the G3 for distinguished service in the or conflicts within applied genetics. -

Duke University Dissertation Template

Life History Tradeoffs and Genetic Variation for Social Behaviors in a Wild Primate Population by Emily McLean University Program in Genetics and Genomics Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Susan Alberts, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Rausher, Chair ___________________________ Mohamed Noor ___________________________ Jenny Tung ___________________________ Elizabeth Archie Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Genetics and Genomics of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Life History Tradeoffs and Genetic Variation for Social Behaviors in a Wild Primate Population by Emily McLean University Program in Genetics and Genomics Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Susan Alberts, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Rausher, Chair ___________________________ Mohamed Noor ___________________________ Jenny Tung ___________________________ Elizabeth Archie An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University Program in Genetics and Genomics in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Emily McLean 2018 Abstract Understanding the genetic and environmental forces that contribute to phenotypic variation is a major goal of evolutionary biology. However, social living blurs the distinction between genes and environments because the social environment is (at least in part) determined by the genes of its members. Therefore, the genes that influence an individual’s phenotype are not limited to his own genes (direct genetic effects) but potentially include the genes of individuals in his social context (indirect genetic effects). Indirect genetic effects are thought to be of particular importance in the evolution of social behavior. Social living is a common phenotype in many animal taxa and is especially well-developed in non-human primates and humans. -

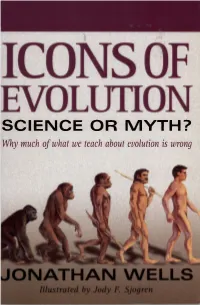

Why Much of What We Teach About Evolution Is Wrong/By Jonathan Wells

ON SCIENCE OR MYTH? Whymuch of what we teach about evolution is wrong Icons ofEvolution About the Author Jonathan Wells is no stranger to controversy. After spending two years in the U.S. Ar my from 1964 to 1966, he entered the University of California at Berkeley to become a science teacher. When the Army called him back from reser ve status in 1968, he chose to go to prison rather than continue to serve during the Vietnam War. He subsequently earned a Ph.D. in religious studies at Yale University, where he wrote a book about the nineteenth century Darwinian controversies. In 1989 he returned to Berkeley to earn a second Ph.D., this time in molecular and cell biology. He is now a senior fellow at Discovery Institute's Center for the Renewal of Science and Culture (www.discovery.org/ crsc) in Seattle, where he lives with his wife, two children, and mother. He still hopes to become a science teacher. Icons ofEvolution Science or Myth? Why Much oJWhat We TeachAbout Evolution Is Wrong JONATHAN WELLS ILLUSTRATED BY JODY F. SJOGREN IIIIDIDIREGNERY 11MPUBLISHING, INC. An EaglePublishing Company • Washington, IX Copyright © 2000 by Jonathan Wells All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or trans mitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including pho tocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast. -

“The Church of the Homeless Jesus As a Home for the Holidays” Advent 4C (December 23, 2018) Rev. Dr. David A. Kaden >>

1 “The Church of the Homeless Jesus as a Home for the Holidays” Advent 4C (December 23, 2018) Rev. Dr. David A. Kaden >>Put a hand on our shoulder and point us in the right direction. Put our hand on someone’s shoulder and let it matter. Amen<< On Friday, Jerry Coyne, Emeritus Professor of Ecology and Evolution at the University of Chicago, published a piece titled, “Yes, There is a War between Science and Religion.”1 Science, he writes, searches for “truth about the universe” through observation, “doing experiments,” and “replicating … [the] results.” Religion, on the other hand, he says, searches for truth “via dogma, scripture, and authority.” “The conflict between [them],” he says, “rests on the [conflicting] methods they use to decide what is truth … .” I winced when I read Coyne’s characterization of religion with the words “dogma” and “authority.” I wonder if he’s ever been to a UCC church! Friday’s article was not the first time Coyne made this argument. He published a book on the conflict between science and religion back in 2015, which won mixed reviews in the Washington Post, The Atlantic, and others. Mixed reviews, because it seems that whenever scientists venture of course into the churning waters of the religious world, in order to criticize religion, they tend to take aim at the easy conservative religious targets: Coyne’s easy target is the dismissal of climate change by some more conservative people of faith, who ignore the warnings of scientists - an example of people of faith venturing off course into the world of science. -

Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation Roger Butlin, Carole Smadja

Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation Roger Butlin, Carole Smadja To cite this version: Roger Butlin, Carole Smadja. Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation. American Naturalist, Uni- versity of Chicago Press, 2018, 191 (2), pp.155-172. 10.1086/695136. hal-01945350 HAL Id: hal-01945350 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01945350 Submitted on 5 Dec 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License vol. 191, no. 2 the american naturalist february 2018 Synthesis Coupling, Reinforcement, and Speciation Roger K. Butlin1,2,* and Carole M. Smadja1,3 1. Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study, Wallenberg Research Centre at Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch 7600, South Africa; 2. Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, The University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TN, United Kingdom; and Department of Marine Sciences, University of Gothenburg, Tjärnö SE-45296 Strömstad, Sweden; 3. Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution, Unité Mixte de Recherche 5554 (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique–Institut de Recherche pour le Développement–École pratique des hautes études), Université de Montpellier, 34095 Montpellier, France Submitted March 15, 2017; Accepted August 28, 2017; Electronically published December 15, 2017 abstract: During the process of speciation, populations may di- Introduction verge for traits and at their underlying loci that contribute barriers Understanding how reproductive isolation evolves is key fl to gene ow. -

MOHAMED NOOR Earl D

MOHAMED NOOR Earl D. McLean Professor and Chair, Department of Biology BIOGRAPHY Mohamed Noor wants to answer one of the greatest unsolved questions in biology: How constant evolutionary change produces the discontinuous groups known as species. As technology improves Dr. Noor’s work gets closer to the answer. Recently, his research team used fruit fly species to understand the causes and evolutionary [ Faculty Fellow through December 2017 ] consequences of variation in rates of genetic recombination. Now, his team is working to determine the genetic features and evolutionary EDUCATION processes that allow hybridizing species to persist. From reframing foundational principles of biology to applying modern approaches like Cornell University, Section of Genetics and whole-genome sequencing, Noor explores a wide range of scientific Development, Post-doc, 1996-98 topics to figure out what makes organisms similar and at the same University of Chicago, Ecology and Evolution, time unique. Ph.D., 1996 College of William and Mary, Biology, B.S., 1992 Dr. Noor’s innovative techniques are not limited to his research. He has developed a popular online course, “Introduction to Genetics and Evolution,” and uses the ‘flipped classroom” technique to deliver TOPICS traditional lecture material online so that his class can discuss the material the next day. This allows Noor to interact with his 400 students and to address specific topics during his precious class time. Genetics and evolution In 2012, Dr. Noor was the recipient of the ADUTA award for teaching Molecular evolution excellence, a student-nominated and selected award, given by the Evolution by natural selection Duke Alumni Association. -

Why Evolutionary Psychology Is 'True". a Review of Jerry Coyne, Why

Evolutionary Psychology www.epjournal.net – 2009. 7(2): 288-294 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ Book Review Why Evolutionary Psychology is “True” 1 A review of Jerry Coyne, Why Evolution is True. Viking Penguin: New York, 2009, 304 pp., US$27.95, ISBN-13 978-0-670-02053-9 (hardcover) James R. Liddle, Florida Atlantic University, Department of Psychology, Davie, FL 33314 USA, Email: [email protected] (corresponding author). Todd K. Shackelford, Florida Atlantic University, Department of Psychology, Davie, FL 33314 USA, Email: [email protected]. Jerry Coyne is a professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolution at the University of Chicago. In Why Evolution is True (WEIT), he undertakes a daunting task: to provide a thorough yet concise and readable account of the evidence in support of evolution. It is difficult to overstate Coyne’s success in meeting this goal. From fossils and embryos to biogeography and speciation, Coyne not only reviews detailed evidence for evolution, but also explains why this evidence is exactly what we would expect to find if evolution were true, all with a writing style that is engaging and accessible. Coyne is also successful in what is obviously another of his goals, which is to provide a devastating response to creationist arguments. Several reviews have summarized the many excellent aspects of WEIT (e.g., Dawkins, 2009; Futuyma, 2009; Padian, 2009). In this review, we address an aspect of WEIT that appears to have been mentioned in just one other review. Futuyma (2009) briefly mentions Coyne’s critique of evolutionary psychology, suggesting that “one might make more allowance for the possible validity of hypotheses in this field” (p. -

Did Kettlewell Commit Fraud? Re-Examining The

www.ssoar.info Did Kettlewell commit fraud? Re-examining the evidence Rudge, David Wÿss Postprint / Postprint Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: www.peerproject.eu Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Rudge, D. W. (2005). Did Kettlewell commit fraud? Re-examining the evidence. Public Understanding of Science, 14(3), 249-268. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662505052890 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter dem "PEER Licence Agreement zur This document is made available under the "PEER Licence Verfügung" gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zum PEER-Projekt finden Agreement ". For more Information regarding the PEER-project Sie hier: http://www.peerproject.eu Gewährt wird ein nicht see: http://www.peerproject.eu This document is solely intended exklusives, nicht übertragbares, persönliches und beschränktes for your personal, non-commercial use.All of the copies of Recht auf Nutzung dieses Dokuments. Dieses Dokument this documents must retain all copyright information and other ist ausschließlich für den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen information regarding legal protection. You are not allowed to alter Gebrauch bestimmt. Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments this document in any way, to copy it for public or commercial müssen alle Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise purposes, to exhibit the document in public, to perform, distribute auf gesetzlichen Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses or otherwise use the document in public. Dokument nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated Sie dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke conditions of use. vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

Reproductive Isolation Between Two Species T. Freemani

Heredity72 (1994) 155—1 62 Received 14 June 1.993 Genetical Society of Great Britain Reproductive isolation between two species of flour beetles, Tribolium castaneum and T. freemani: variation within and among geographical populations of T castaneum MICHAEL J. WADE* & NORMAN A. JOHNSON Department of Ecology and Evolution, 1101 E. 57th Street, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL 60637,USA Tribolium casraneum and T freernani produce sterile hybrid progeny in reciprocal crosses. The reciprocal crosses differ significantly in the mean numbers of progeny, progeny sex ratios, hybrid male body size and male antennal and leg morphologies. These results suggest an effect of either the X chromosome or the cytoplasm on characteristics of F1 hybrids. In contrast, large X chromosome effects on morphological traits are not usually oberved in interspecific crosses among drosophilid flies. We also report large, significant differences in progeny numbers, body mass and degree of female bias in sex ratio between different geographic strains of T castaneum when mated in reciprocal crosses with T freemani. Sex ratio bias also varies significantly among matings within geographic strains of T castaneum. When T castaneum males are mated with T freemani females, but not in the reciprocal cross, the F1 sex ratio is female biased, uncorrelated with family size and ranges from 57.14 per cent to 72.23 per cent female, depending on the geographic strain of the T castaneum male. Keywords: hybridinviability, genetic variation,morphology, reproductive isolation, speciation, Tribolium sex that is most adversely affected. This rule applies to Introduction taxa in which males are the heterogametic sex (includ- Dobzhansky(1937),Mayr(1963) and others (Coyne et ing beetles) as well as in cases wherein females are the al., 1988; Coyne, 1992b; Wu & Davis, 1993) have heterogametic sex.