Citizenshipasatoolofstate-Buildingin Kosovo:Status,Rights,Andidentityin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VISA POLICIES in SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE EWI Policy Brief

November 2006 VISA POLICIES IN SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE EWI Policy Brief VISA POLICIES IN SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE: A HINDRANCE OR A STEPPING STONE TO EUROPEAN INTEGRATION? By Martin Baldwin-Edwards Edited by Lejla Haveric and Marina Peunova i MISSION Founded in 1980, the EastWest Institute works to promote solutions that reduce threats to peace and security. International and action-oriented, EWI is nonpartisan and independent. WHAT WE DO • We bring together leaders from government, business, military, media and other sectors of society in confi dential and public dialogue to tackle intractable problems, build trust, reconcile disparate views and reframe issues. • We address dangerous fault lines between the emerging East and the West. We serve as an institution of choice for state and non-state actors who seek to cooperate, prevent confl ict and manage global challenges. • We identify, help develop and support emerging leaders as we build a global community committed to confl ict prevention and security. www.ewi.info About the Author Martin Baldwin-Edwards is co-director of the Mediterranean Migration Observatory, Panteion University, Athens, Greece. He contributed to the regional study for the Global Commission on International Migration on Th e Middle East and the Mediterranean, has served as a consultant on immigration to two European governments, and is the author of more than fi ft y publications on international migration, including Th e Politics of Immigration in Western Europe (ed. with M Schain, 1994) and Immigrants and the Informal Economy in Southern Europe (ed. with J Arango, 1999). About the EastWest Institute’s Work in South Eastern Europe The EastWest Institute has over a decade of experience working in South Eastern Europe and currently operates a number of cross-border cooperation projects aimed at promoting stability across the region. -

After the Red Passport: Towards an Anthropology of the Everyday Geopolitics of Entrapment in the EU’S ‘Immediate Outside’

After the red passport: towards an anthropology of the everyday geopolitics of entrapment in the EU’s ‘immediate outside’ Stef Jansen Manchester University Suggesting building bricks for an anthropology of everyday geopolitics, this text analyses affective engagements with regulation, here of cross-border mobility. Following the logic of the regulation that constitutes them, I conceptualize zones of humiliating entrapment through documentary requirements – experienced by citizens of Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia – as the EU’s shrinking ‘immediate outside’. Using ethnography, I embed bodily experiences in visa queues in people’s engagements with changing Eurocentric spatiotemporal rankings, refracting this entrapment against the privileges of certain foreigners (such as me) and against their own remembered mobility with the ‘red’ Yugoslav passport. I propose that complementing the dominant focus on the role of (national) identity politics in geopolitical affect with one on regulation and ranking is a central task for a critical anthropology of everyday geopolitics in peripheries. In 2008, some friends and I were having a beer in Sarajevo when an acquaintance of theirs joined our table. He asked me what had brought me to Sarajevo and I gave him my well-worn, one-minute reply. He then asked me:‘So you chose to be here?’ Rising to the bait of his irony I replied that, yes, I had been lucky enough to develop my research project myself and that I enjoyed being there, adding in jest: ‘Nikomenetjeradaprovodimvrijemeovdje’ [‘Nobody is forcing me to spend time here’]. At that moment my friend intervened without blinking an eyelid:‘Da je tako, bio bi Bosanac!’ [‘If that were the case (i.e. -

Foreign Nationals

Foreign Nationals In most cases, you will need a residence permit that allows self-employment before you can en- ter into an independent contractor agreement or fee agreement. Provided your residence permit allows gainful employment (“Erwerbstätigkeit gestattet”), any gainful work is allowed and you do not need any further permission. If you have a residence permit for another reason, you must request a change to the condi- tions. If you do not have a residence permit, you must apply for one (fees apply). Before you perform any work or provide any services contact the Hamburg Welcome Center: http://welcome.hamburg.de. You can arrange an appointment via email: [email protected] (Current waiting period for an appointment: up to 3 months.) Alternatively, contact your local district office—check here for your nearest office: www.hamburg.de/behoerden- finder/hamburg/11254942 Generally, you will need to present the following documents to be issued with a residence per- mit: passport or national identification card biometric photograph current certificate of residence proof of sufficient health insurance coverage Note: If you do not have statutory health insurance, you must provide proof that you have private health insurance. completed and signed registration form administration fees additional documents as necessary See here for more information and forms (also in other languages): http://welcome.hamburg.de/formulare If you have any questions, contact the member of the Strategic Purchasing department responsi- ble for independent contractor agreements and fee agreements (732): www.uni-ham- burg.de/uhh/organisation/praesidialverwaltung/finanz-und-rechnungswesen/einkauf/strate- gischer-einkauf/werkvertraege.html See the following pages for more information on the different employment groups / countries of origin. -

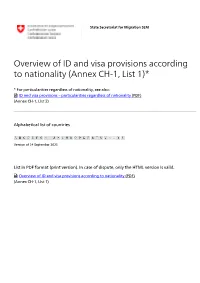

Overview of ID and Visa Provisions According to Nationality (Annex CH-1, List 1)*

State Secretariat for Migration SEM Overview of ID and visa provisions according to nationality (Annex CH-1, List 1)* * For particularities regardless of nationality, see also: ID and visa provisions – particularities regardless of nationality (PDF) (Annex CH-1, List 2) Alphabetical list of countries Version of 14 September 2021 List in PDF format (print version). In case of dispute, only the HTML version is valid. Overview of ID and visa provisions according to nationality (PDF) (Annex CH-1, List 1) A Country National passports and Visa required for stays Visa required for stays (Countries in italics: not other travel documents of up to 90 daysB) of more than 90 daysC) recognized by Switzerland) authorizing entry into Switzerland Afghanistan see A) Yes V Yes Albania see A) No V12 Yes F: D M: D Algeria see A) Yes V Yes F: D, S M: D, S Andorra see A) No No Angola see A) Yes V Yes F: D, S M: D, S Antigua and Barbuda see A) No V1 Yes Argentina see A) No V1 Yes Armenia see A) Yes V Yes F: D M: D Australia see A) No V1 Yes Austria P5 No No (Schengen) ID Azerbaijan see A) Yes V Yes M: D, S* B Country National passports and Visa required for stays Visa required for stays (Countries in italics: not other travel documents of up to 90 daysB) of more than 90 daysC) recognized by Switzerland) authorizing entry into Switzerland Bahamas see A) No V1 Yes Bahrain see A) Yes V Yes Bangladesh see A) Yes V Yes Barbados see A) No V1 Yes Belarus see A) Yes V Yes Belgium P5 No No (Schengen) ID SB BEL-1 Belize see A) Yes V Yes Benin see A) Yes V Yes F: D, -

Requirments to Travel in Croatia

REQUIRMENTS TO TRAVEL IN CROATIA SCHENGEN COUNTRIES: AUSTRIA FINLAND ICELAND LUXEMBOURG PORTUGAL SWITZERLAND BELGIUM FRANCE ITALY MALTA SLOVAKIA CZECH GERMANY LATVIA NETHERLANDS SLOVENIA REPUBLIC DENMARK GREECE LEICHTENSTEIN NORWAY SPAIN ESTONIA HUNGARY LITHUANIA POLAND SWEDEN NATIONALITIES REQUIRING VISA TO ENTER CROATIA: A D J N ST. TOME AND PRINCIPE AFGHANISTAN DJIBOUTI JAMAICA NAMIBIA SUDAN ALBANIA DOMINICAN JORDAN NAURU SURINAME REPUBLIC ALGERIA NEPAL T ANGOLA E K NIGER TAIWAN ARMENIA ECUADOR KAZAKHSTAN NIGERIA TAJIKISTAN AZERBAIJAN EGYPT KENYA NORTH KOREA TANZANIA EQUATORIAL KOSOVO THAILAND GUINEA B ERITREA KUWAIT O TOGO BAHRAIN KYRGYZSTAN OMAN TUNIS BANGLADESH F TURKEY BELARUS FIJI L P TURKMENISTAN BELIZE LAOS PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY BENIN G LEBANON PAPUA NEW U GUINEA BHUTAN GABON LESOTHO PHILIPPINES UGANDA BOLIVIA GAMBIA UKRAINE BOSNIA AND GEORGIA M Q UZBEKISTAN HERZEGOVINA BOTSWANA GHANA MACEDONIA QUATAR BURKINA FASO GUINEA MADAGASCAR V BURUNDI GUINEA BISSAU MALAWI R VIETNAM C GUYANA MALDIVES RUSSIA CAMBODIA MALI RWANDA Y CAMEROON H MAURITANIA YEMEN CAPE VERDE HAITI MOLDOVA S CENTRAL AFRICAN MONGOLIA SAUDI ARABIA Z REPUBLIC CHAD I MONTENEGRO SENEGAL ZAMBIA CHINA INDIA MOROCCO SERBIA ZIMBABWE COMOROS INDONESIA MOZAMBIQUE SIERRA LEONE CONGO IRAN MYANMAR/ BURMA SOMALIA 1 COTE D'IVOR IRAQ SOUTH AFRICA CUBA SRI LANKA VISA FOR CROATIA: Please note it is very important that the visa is multiple or double entry. If it is a single entry, a passenger cannot travel to Venice on a day trip, because the passenger will not have a permission to re-enter Croatia in the evening. IMPORTANT: Passengers who require a visa for Croatia can use either of the following, instead of a Croatian visa: Schengen residence permit- issued by one of the Schengen area member states. -

List of Countries for Which a Visa Is Necessary

ATTACHMENT I to the Reg. CE 539/2001: COUNTRIES FOR WHOM A VISA IS NECESSARY Afghanistan Ghana Russia Algeria Guinea Rwanda Angola Guinea-Bissau São Tomé and Príncipe Saudi Arabia Guyana Senegal Armenia Haiti Sierra Leone Azerbaijan India Somalia Bahrein Indonesia South Africa Bangladesh Iran South Sudan Belarus Iraq Sri Lanka Belize Ivory Coast/Côte d'Ivoire Sudan Benin Jamaica Suriname Bhutan Jordan Swaziland Burma/Myanmar Kazakhstan Syria Bolivia Kenya Tajikistan Botswana Kuwait Thailand Burkina Faso Kyrgyzstan Tanzania Burundi Laos Togo Cambodia Lebanon Tunisia Cameroon Lesotho Turkey Cape Verde Liberia Turkmenistan Central African Republic Libya Ukraine Chad Madagascar Uganda China Malawi Uzbekistan Comoros Maldives Vietnam Congo Mali Yemen Cuba Mauritania Zambia Democratic Republic of Mongolia Zimbabwe Congo Morocco Djibouti Mozambique Dominican Republic Namibia NB: The citizens of some Ecuador Nepal countries not present on Egypt Niger this list are exempt from Eritrea Nigeria the requirement of a visa Equatorial Guinea North Korea only under certain Ethiopia Oman circumstances. Please, Fiji Pakistan therefore, also read the Gabon Papua New Guinea second part of this Gambia Philippines document. Georgia Qatar For an on-line verification: http://vistoperitalia.esteri.it/home.aspx ATTACHMENT II to the Reg. CE 539/2001 EXEMPTION FROM THE REQUIREMENT OF A VISA 1. Countries exempt from the requirement of a visa Albania (exemption only for those with biometric passports) Andorra Antigua and Barbuda (the exemption accord will be signed -

The Challenge of Building an Independent Citizenship Regime in a Partially Recognised State: the Case of Kosovo

The challenge of building an independent citizenship regime in a partially recognised state: the case of Kosovo Gëzim Krasniqi Working Paper 2010/04 _,_ IDEAS University of Edinburgh, School of Law The Europeanisation of Citizenship in the Successor States of the Former Yugoslavia (CITSEE) The challenge of building an independent citizenship regime in a partially recognised state: the case of Kosovo Gezim Krasniqi This paperhasbeenproduced in close collaboration with theEuropeanUnionDemocracyObservatory on Citizenship (EUDO-Citizenship) and has been made available as a EUDO country report on www.eudo-citizenship.eu. The paper followed the EUDO structure for country reports presenting historical background, current citizenship regimes and recent debates on citizenship matters in the country under scrutiny. Other materials that complement this paper such as citizenship-related legislation, citizenship news,chronology, adoptedinternational conventions andbibliography are also available on the EUDO website. The Europeanisation of Citizenship in the Successor States of the Former Yugoslavia (CITSEE) CITSEE WorkingPaperSeries2010/04 Edinburgh, Scotland, UK ISSN 2046-4096 The University of Edinburgh is a charitable body, registered in Scotland, with registration number SC005336. © 2010 Gezim Krasniqi This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. Requests should be addressed to [email protected] The viewexpressed -

List 1: Overview of ID and Visa Provisions According to Nationality (Version of 25 May 2010)

Federal Department of Justice and Police FDJP Federal Office of Migration FOM Entry, Stay and Return Directorate Entry and Admission Department List 1: Overview of ID and visa provisions according to nationality (version of 25 May 2010) Country National passports♦ and other Visa required for Visa required for (Countries in italics: not recog- travel documents authorizing en- stays of up to 3 stays of more than 3 nized by Switzerland) try into Switzerland months months Afghanistan B, ST YesV Yes Albania SB YesV, V7 YesV7 Algeria SB YesV, V2 YesV2 Andorra No No Angola SB YesV Yes Antigua and Barbuda SB NoV1 Yes Argentina SB, K NoV1 Yes Armenia YesV, V7 YesV7 Australia NoV1 Yes Austria (Schengen) P5, ID No No Azerbaijan YesV Yes Bahamas NoV1 Yes Bahrain YesV Yes Bangladesh YesV Yes Barbados SB NoV1 Yes Belarus SB YesV Yes Belgium (Schengen) P5, ID, SB, 1 No No Belize YesV Yes Benin YesV Yes Bhutan YesV Yes Bolivia YesV, V5 Yes Bosnia and Herzegowina YesV, V2 Yes B “Business Passport” ID Identity card K Consular passport P5 Passport expired for less than five years SB Seaman’s book ST Student passport 1 French or Luxembourg identity cards for foreign nationals (these ID cards must prove that the holder has Belgian citizenship); children’s ID for under 15-year olds, for children less than 12 years old travelling accompanied by their parents (also valid without photo); tempo- rary Belgian identity card. V Third state members in possession of both a valid permanent residence permit issued by a Schengen member state (cf. -

Serbia to Ease Travel for Foreigners Coming from Kosovo

Inside Prishtina: History of the OSCE building October 30 - November 12, 2009 Issue No. 26 www.prishtinainsight.com Free copy Kosovo’s New Image OPINION to Attract Prishtina Investment and Candidates in Recognitions Election Debate Spain and The Hague to be targeted as part of 6million euro campaign > page 6 An international campaign to transform Kosovo’s image ARTE was launched on Monday with Jazzing up the slogan “Kosovo – The Prishtina Young Europeans”. > page 9 Turn to page 5 for the full story GUIDE Coastal Montenegro: Archaeological Oasis Serbia to Ease Travel for Foreigners of the eastern Coming From Kosovo Adriatic Interior minister will lift restrictions on foreign nationals crossing from Kosovo into Serbia - but no change in sight for > page 8 Kosovo passport holders. one can cross over without a prob- porarily administered by the UN Kosovo-Serbia border for hours FOOD & DRINK By Lawrence Marzouk lem,” the Interior Minister said. under UN Resolution 1244. As such, because some members of the con- No Revolution at “There will be stamps annulling all although it does not control voy, trying to return to the UK, had erbia is to lift restrictions on Kosovo visas or stamps from the so- Kosovo’s land and air borders, it flown into Pristina. foreign passport-holders trav- Prishtina’s Favourite called Republic of Kosovo.” considers those entering the coun- From January 1, Serbia expects to Selling from Kosovo to Serbia, Chinese Dacic, who comes from Prizren, try through these ports ‘illegally join the European Union’s so-called the Serbian Interior Minister has refused to provide a date for the lift- present’ in Serbia. -

Issn 1452 -8851

ISSN 1452 -8851 садрЖај CONTENTS 4 Atlantis Osnivač i izdavač / Founder and Publisher: Atlantski savet Srbije / Th e Atlan- Шта доноси tic Council of Serbia чланство у Uređivački odbor izdanja At- lantskog saveta Srbije / Edito- rial Board: Branislav Anđelić, Партнерству за мир dr Srbobran Branković, Ro- doljub Gerić, prof. dr Darko Benefi ts of Partnership Marinković, Miloš Ladičorbić, Blagoje Ničić, Petar Popović • Za izdavača / For the Publisher: for Peace membership Vladan Živulović, predsednik / President • Glavni i odgovorni urednik / Editor-In-Chief: Ro- 8 doljub Gerić • Redakcija / Edito- rial Work: Jelena Jeličić, Milan Jovanović, Ivana Kojadinović, Mihailo Ilić, Ana Đorđević, Ale- Брзим кораком ksandar Đelošević, Ana Komar- nicki • Likovno-grafi čki urednik / Graphics & Layout: Branislav до Европе Ninković & Dejan Cvetković • PrePRESS: triD studio, www.trid. co.yu • Sekretar redakcije / Edi- In the fast lane torial Secretary: Senka Kankaraš • Prevod na engleski / English to Europe Translation: Nikolina Šašo • Le- ktor za engleski jezik / English language editor: Nikolina Šašo 34 • Adresa Redakcije / Editorial Offi ce Address: 11000 Beograd, Bul. oslobođenja 83 / Boul- evard oslobođenja 83, Belgrade Интервју: Хозе Риеара Сикјер 11 000, Serbia • E-mail adresa / E-mail Address: atlantis@atlan- ticcouncil.org.yu • Elektronsko Србија ће бити izdanje / Electronic Publication: www.atlanticcouncil.org.yu • Tel/fax: +381 11 3975-643, 2493- чланица ЕУ 096, 2493-356 • Časopis izlazi tromesečno / Atlantis is a quar- Interview: José Riera -

Repatriation Information

REPATRIATION INFORMATION Postal details of countries accredited to New Zealand are included. Phone, fax and email details can be found on www.mfat.govt.nz/Embassies/2-Foreign-Embassies/index.php Afghanistan Argentina 5. Statement from the receiving Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Embassy of the Argentine Republic funeral director (or cemetery) in Afghanistan PO Box 5430, Lambton Quay Austria that the shipment will be PO Box 155, Deakin West Wellington 6154 received at the border crossing Canberra, ACT 2600, Australia point and that the shipment is General desired and permitted. General 1. Embalming. 1. Embalming. 2. Use of a hermetically sealed 2. Use of a hermetically sealed casket. Bangladesh casket. 3. Use of all-wood outer shipping Consulate of the Peoples Republic 3. Use of all-wood outer shipping container. of Bangladesh PO Box 10048, Wellington container. Documentation Documentation 1. Certified copy of the death General 1. Certified copy of the death certificate. 1. Embalming. certificate. 2. Embalmer’s (non-contraband) 2. Use of a hermetically sealed 2. Locally issued burial and/or certificate. casket. transit permit. 3. Use of all-wood outer shipping container. Australia Documentation Albania Australian High Commission PO Box 4036, Wellington 6140 1. Certified copy of the death General certificate. 1. Embalming. General 2. Locally issued burial and/or 2. Use of a hermetically sealed 1. Embalming. transit permit. casket. 2. Use of a hermetically sealed 3. Embalmer’s (non-contraband) 3. Use of all-wood outer shipping casket, made of lead, bronze, certificate. container. zinc or steel or polythene 4. Passport Documentation plastic sheeting with a minimum thickness of 0.26mm. -

Overview of ID and Visa Provisions According to Nationality*

State Secretariat for Migration SEM Annex 1, list 1: nationality Overview of ID and visa provisions according to nationality* * For particularities regardless of nationality, see Annex 1, List 2 Alphabetical list of countries Version of 17 August 2018 List in PDF format (print version). In case of dispute, only the HTML version is valid. Annex 1, List 1: Overview of ID and visa provisions according to nationality (PDF, 829.38 KB) A Country National passports and Visa required for stays Visa required for stays (Countries in italics: not other travel documents of up to 90 daysB) of more than 90 daysC) recognized by Switzerland) authorizing entry into Switzerland Afghanistan see A) Yes V Yes Albania see A) No V12 Yes F: D M: D Algeria see A) Yes V Yes F: D, S M: D, S Andorra see A) No No Angola see A) Yes V Yes F: D, S M: D, S Antigua and Barbuda see A) No V1 Yes Argentina see A) No V1 Yes Armenia see A) Yes V Yes F: D M: D Australia see A) No V1 Yes Austria P5 No No (Schengen) ID Azerbaijan see A) Yes V Yes M: D, S* B Country National passports and Visa required for stays Visa required for stays (Countries in italics: not other travel documents of up to 90 daysB) of more than 90 daysC) recognized by Switzerland) authorizing entry into Switzerland Bahamas see A) No V1 Yes Bahrain see A) Yes V Yes Bangladesh see A) Yes V Yes Barbados see A) No V1 Yes Belarus see A) Yes V Yes Belgium P5 No No (Schengen) ID SB BEL-1 Belize see A) Yes V Yes Benin see A) Yes V Yes F: D, S M*: D, S Bhutan see A) Yes V Yes F: D, S, OP M: D, S, OP Bolivia see