Appendices and Glossary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uk Licensed Products Nov 2020

UK LICENSED PRODUCTS NOV 2020 Product Brand Product Name Company number Alara Wholefoods Alara Wholefoods OATS-GB-001-009 Organic Gluten Free Scottish Oats Porridge Ltd Green's Beers GB-004-001 Discovery Greens Beers Green's Beers GB-004-002 Dry Hopped Lager Green's Beers GB-004-003 Pilsner Green's Beers GB-004-004 Golden Ale Green's Beers GB-004-005 Blond Green's GB-004-007 Dark Ale Green's Beers GB-004-007 Dark Green's Beers GB-004-008 India Pale Ale Green's Beers GB-004-009 Tripel Green's Beers GB-004-010 Dubbel Lovemore GB-006-002 Apple and Sultana cookies x2 Welsh Hills Bakery Lovemore GB-006-005 Chocolate Brownie Slices x2 Lovemore GB-006-006 Chocolate Brownie Slice Lovemore GB-006-007 Chocolate Chip Cookies Lovemore GB-006-008 Chocolate Chip Cookies Lovemore GB-006-010 Deep Filled Mince Pies Lovemore GB-006-011 Digestive Biscuits Lovemore GB-006-014 Gingerbread Men Lovemore GB-006-017 Lemon Cake Slices Lovemore GB-006-018 Fruit Cake mini slice Lovemore GB-006-019 Fruit Cake Slices Lovemore GB-006-021 Apple Pies Lovemore GB-006-022 Cherry Bakewells Lovemore GB-006-023 Chocolate Celebration Cake Lovemore GB-006-024 Chocolate Muffins Lovemore GB-006-025 Crispbreads Lovemore GB-006-026 Custard Creams Lovemore GB-006-027 Double Chocolate Cookies Lovemore GB-006-028 Jammy Wheels Lovemore GB-006-029 Chocolate Cake mini slice Lovemore GB-006-030 Madeira Cake mini slice Lovemore OATS-GB-006-031 Oat Crunch Cookies Lovemore GB-006-032 O'Chocos Lovemore GB-006-033 Shortbread Fingers Welsh Hills Bakery GB-006-034 Dundee Welsh Hills Bakery GB-006-036 -

Psychological Science

Psychological Science http://pss.sagepub.com/ Sensory-Specific Satiety Is Intact in Amnesics Who Eat Multiple Meals Suzanne Higgs, Amy C. Williamson, Pia Rotshtein and Glyn W. Humphreys Psychological Science 2008 19: 623 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02132.x The online version of this article can be found at: http://pss.sagepub.com/content/19/7/623 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Association for Psychological Science Additional services and information for Psychological Science can be found at: Email Alerts: http://pss.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://pss.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Downloaded from pss.sagepub.com at University of Aberdeen on August 24, 2010 PSYCHOLOGICAL SCIENCE Research Report Sensory-Specific Satiety Is Intact in Amnesics Who Eat Multiple Meals Suzanne Higgs, Amy C. Williamson, Pia Rotshtein, and Glyn W. Humphreys University of Birmingham ABSTRACT—What is the relationship between memory and Despite these intriguing findings, little is known about the appetite? We explored this question by examining prefer- mechanisms underlying multiple-meal eating in amnesia. ences for recently consumed food in patients with amnesia. Because the procedure in previous studies has been to offer the Although the patients were unable to remember having same meals in succession, one explanation is that the usual eaten, and were inclined to eat multiple meals, we found decline in palatability and intake of a food that has been eaten to that sensory-specific satiety was intact in these patients. satiety is disrupted in amnesia (Rolls, Rolls, Rowe, & Sweeney, The data suggest that sensory-specific satiety can occur in 1973). -

Port, Sherry, Sp~R~T5, Vermouth Ete Wines and Coolers Cakes, Buns and Pastr~Es Miscellaneous Pasta, Rice and Gra~Ns Preserves An

51241 ADULT DIETARY SURVEY BRAND CODE LIST Round 4: July 1987 Page Brands for Food Group Alcohol~c dr~nks Bl07 Beer. lager and c~der B 116 Port, sherry, sp~r~t5, vermouth ete B 113 Wines and coolers B94 Beverages B15 B~Bcuits B8 Bread and rolls B12 Breakfast cereals B29 cakes, buns and pastr~es B39 Cheese B46 Cheese d~shes B86 Confect~onery B46 Egg d~shes B47 Fat.s B61 F~sh and f~sh products B76 Fru~t B32 Meat and neat products B34 Milk and cream B126 Miscellaneous B79 Nuts Bl o.m brands B4 Pasta, rice and gra~ns B83 Preserves and sweet sauces B31 Pudd,ngs and fru~t p~es B120 Sauces. p~ckles and savoury spreads B98 Soft dr~nks. fru~t and vegetable Ju~ces B125 Soups B81 Sugars and artif~c~al sweeteners B65 vegetables B 106 Water B42 Yoghurt and ~ce cream 1 The follow~ng ~tems do not have brand names and should be coded 9999 ~n the 'brand cod~ng column' ~. Items wh~ch are sold loose, not pre-packed. Fresh pasta, sold loose unwrapped bread and rolls; unbranded bread and rolls Fresh cakes, buns and pastr~es, NOT pre-packed Fresh fru~t p1es and pudd1ngs, NOT pre-packed Cheese, NOT pre-packed Fresh egg dishes, and fresh cheese d1shes (ie not frozen), NOT pre-packed; includes fresh ~tems purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh meat and meat products, NOT pre-packed; ~ncludes fresh items purchased from del~catessen counter Fresh f1sh and f~sh products, NOT pre-packed Fish cakes, f1sh fingers and frozen fish SOLD LOOSE Nuts, sold loose, NOT pre-packed 1~. -

SOUTH AUSTRALIA Product Catalogue July 2019 About Balfours a South Australian Icon

SOUTH AUSTRALIA Product Catalogue July 2019 About Balfours A South Australian icon. Balfours was established in 1853 at 130 Rundle Street and is now Australia’s oldest manufacturers of baked goods. When James Calder and his wife Margaret Balfour arrived in Adelaide, they brought with them the finest traditions of European baking. Through prosperous times, depressions and two world wars we’ve kept those traditions alive with our much-loved range of premium cakes and pastries. Today, Balfours is still wholly South Australian-owned. Our products are baked with the same pride and dedication to quality that has distinguished us since our earliest days. Why Balfours? Balfours continues to strive for quality products and faultless service. We have a customer-centric approach to business and have vast experience with many kinds of businesses; from schools, swimming pools, and local grocers to large supermarkets, our experience ensures our partners get the right product mix and service to make them profitable. For more information or to talk to a customer service representative call 1300 300 032 or visit balfours.com.au 165 Years of History SOUTH AUSTRALIAN owned and operated We’re proud to offer these services in South Australia: OVER 200 SKUs available MARKETING MATERIAL support for select products FREE NEXT DAY DELIVERY state-wide (Monday to Thursday) LOW minimum order quantities $40 LARGE field team resource available CUSTOMER SERVICE centre open Monday to Friday (6:30am to 4:00pm ACST) ONLINE WEBSTORE customer store for easy and efficient orders Contents FRESH PIES, PASTIES & SAVOURY ROLLS QUICHES TARTS Traditional Footy Pie ........... -

4.1 Branded Food and Drink Higgidy Pies 12Th June 2009 F

Design Business Association Design Effectiveness Awards 2009 Packaging: 4.1 Branded Food and Drink Higgidy Pies 12th June 2009 For Publication Executive Summary Driven by a passion for good food Camilla Footit left her job in 2003 as Head of Food for Starbucks and started producing gorgeous handmade pies. Word spread and soon she was supplying bigger players such as EAT cafés and Booths. All sales were own label however, no-one knew they were eating a Higgidy pie. Realising that the pies they were making were snowballing in popularity and earning a glowing reputation for the cafés and restaurants that stocked them, they began to dream of selling them under their own Higgidy brand. The Higgidy team were recommended Ziggurat Brands and we were ultimately briefed to create a brand identity and packaging for Higgidy Pies. The brand essence we developed of ‘The Uncommon Pie’ was a play on words that refl ected the brand truth, that no-one was making pies of this quality. The story of how Camilla’s passion had started the business and how her husband James, an architect, had given up his tree-house building business to join Camilla became the basis for the identity. Camilla’s suggestion that her personality could be summed up as being ‘pink, passionate and posh’ was the icing on the cake. Visual disruption was essential. A copy story runs around the pack featuring light-hearted illustrations of the key players and the ingredients. A window allows the hand-made features of the pie to be seen and a strong and consistent brand colour provides outstanding range blocking on shelf. -

Aldi, West Ewell Date of Visit: 28.07.18

Store and location: Aldi, West Ewell Date of visit: 28.07.18 Brand Product Sugar reduction category Calorie reduction category soft drinks levy Entrance No promotions in entrance Gondola Ends Store layout does not include gondola ends Trolley checkout area The Foodie market Quinoa bars (Coco & cashew) Biscuits n/a The Foodie market Quinoa bars (Goki & cranberry) Biscuits n/a Passions Popcorn (sweet) Sweet Confectionary n/a Passions Popcorn (sweet & salted) Sweet Confectionary n/a Wrigleys Extra chewing gum (peppermint) n/a n/a Wrigleys Extra chewing gum (spearmint) n/a n/a Wrigleys Extra chewing gum (cool breeze) n/a n/a Wrigleys Extra chewing gum (extra white) n/a n/a Passion Deli Pea snacks (sea salt & vingar) n/a Crisps and savoury snacks Passion Deli Pea snacks (sweet chilli) n/a Crisps and savoury snacks The Foodie market Hike protein bars (Cacao) Biscuits n/a The Foodie market Hike protein bars (Berry) Biscuits n/a Dominion Complimints (strongmint) - sugar free n/a n/a Dominion Complimints (spearmint) - sugar free n/a n/a Dominion Complimints (strongmint) - sugar free n/a n/a Passions Deli Red Lentil Snacks (Tangy tomoto) n/a Crisps and savoury snacks Passions Deli Red Lentil Snacks (barbecue) n/a Crisps and savoury snacks Foodie Market Flatbread thin bites (multi-seed) n/a Savoury biscuits, crackers and crispbreads Foodie Market Flatbread thin bites (cheddar & cracked black pepper) n/a Savoury biscuits, crackers and crispbreads Foodie Market Flatbread thin bites (sweet chilli) n/a Savoury biscuits, crackers and crispbreads Dominion -

Appendices and Glossary

Appendices and glossary Appendix A: Terms of reference and conduct of the inquiry Appendix B: Industry background Appendix C: The companies Appendix D: The Transaction Appendix E: Jurisdiction Appendix F: The counterfactual Appendix G: Competitive effects Appendix H: Tender data Appendix I: Analysis of capacity Appendix J: Barriers to entry Glossary APPENDIX A Terms of reference and conduct of the inquiry Terms of reference 1. On 5 January 2015, the CMA referred the completed acquisition by Pork Farms Caspian Limited of the chilled savoury pastry business of Kerry Foods Limited for an in-depth (phase 2) merger investigation: 1. In exercise of its duty under section 22(1) of the Enterprise Act 2002 (the Act) the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) believes that it is or may be the case that: (a) a relevant merger situation has been created, in that: (i) enterprises carried on by or under the control of Pork Farms Group Limited (formerly named Poppy Acquisition Limited) have ceased to be distinct from the chilled savoury pastry business carried on by or under the control of Kerry Foods Limited; and (ii) the condition specified in section 23(1)(b) of the Act is satisfied; and (b) the creation of that situation has resulted, or may be expected to result, in a substantial lessening of competition within a market or markets in the United Kingdom for goods or services, including in: (i) the branded, own label and convenience retail segments of the supply of cold pies; (ii) the own label and convenience retail segments of the supply of sausage rolls, pasties and slices (when considered in combination), and the branded, own label and convenience retail segments of the supply of sausage rolls (when considered individually); and (iii) the own label retail segment of the supply of hot pies. -

Pork Farms / Kerry Foods: Summary of Hearing with Samworth on 4 March 2015

PORK FARMS CASPIAN / KERRY FOODS MERGER INQUIRY Summary of hearing with Walker and Sons, Ginsters of Cornwall and Tamar Foods, divisions of Samworth Brothers Limited on 4 March 2015 Background 1. Samworth Brothers (Samworth) said it was a privately owned business operating primarily in the manufacture of chilled food. Samworth ran a number of operating divisions which all had a high degree of autonomy. 2. Samworth explained that within the CSP market it operated three main divisions which supplied a wide range of major retailers: (a) Walker and Son (Walkers) predominantly manufactured own-label and branded pork pies ([]% of output). (b) Tamar Foods (Tamar) predominantly manufactured slices and pasties. (c) Ginsters of Cornwall (Ginsters) predominantly manufactured the Ginsters Brand ([]%), although there was some own-label production ([]%). Other divisions within the Samworth Group manufactured some branded product for Ginsters. 3. Samworth explained that one Division would respond to tenders for limited business.1 In tenders for cross category business Samworth would try to create the best customer proposition for the retailer, presenting a single offer. Samworth said that it tried to avoid duplicating investment around the Group by taking into account which Division / site: (a) should lead the negotiation as they had a trading relationship with the retailer, even if the product would be manufactured elsewhere in the Group; (b) specialised in manufacture of the particular product; and 1 For example, if the tender was for cold pies, then Tamar would respond. (c) had the capacity to handle the potential new business. 4. Samworth explained that, within savoury pastry, [] at that time. -

Full Supermarket Data

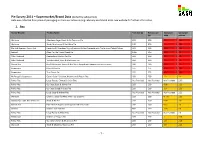

Pie Survey 2011 – Supermarket/Brand Data (Sorted by salt/portion) Data was collected from product packaging in store and online during February and March 2011. See website for further information. 1. Pies Brand/ Retailer Product Name Pack Size (g) Portion size Salt (g) per Salt (g) per (g) 100g portion Waitrose Aberdeen Angus Steak & Ale Top crust Pie 600 300 0.9 2.69 Waitrose Steak, Mushroom & Red Wine Pie 540 270 1 2.69 Marks & Spencer Gastro Pub (main for 1) Aberdeen Angus Steak and Stilton Pie made with Tuxford and Tebutt Stilton 260 260 1.03 2.68 Iceland (Meal for the Family) Steak Pie 1400 350 0.8 2.6 Alfie Chadwick Cumberland Chicken Pot Pie 260 260 1.0 2.5 Alfie Chadwick Yorkshire Beef, Beer & Mushroom Pie 260 260 1.0 2.5 Dorset Pies Beef, Mushroom, Bacon & Red Wine topped with caramelised onion scone 280 280 0.9 2.5 Pieminister Moo & Blue Pie 275 275 0.9 2.43 Pieminister Thai Chook Pie 275 275 0.9 2.43 McDougall's Uppercrust Gastro Style 2 Chicken, Mushroom & Bacon Pies 400 200 1.2 2.4 Pukka Pies Large Potato, Cheese & Onion Pies Not Provided Not Provided Not Provided 2.35 Pukka Pies Our Best Steak & Kidney Pie 200 200 0.98 2.33 Pukka Pies Our Best Baked All Steak Pie 200 200 1.0 2.33 Pukka Pies Large Steak & Kidney Pies Not Provided Not Provided Not Provided 2.33 Waitrose Chicken, Bacon & White Wine Top crust Pie 600 300 0.775 2.33 Sainsbury's Taste The Difference Steak & Ale Pie 250 250 0.93 2.31 Dorset Pies Ham Hock & Apple Cider topped with herb scone 280 280 0.8 2.3 Glenfell Chicken and Ham Pie 680 170 1.25 2.3 Pukka Pies -

• 'Royal Ex-Bats' Grace Palace Gardens • Celeb Scoop with Songs of Praise Presenter JB • Hensus 2017 - the Results! • Gallery - Competitions - Calendar 2018

Issue No.17 Autumn/Winter 2017 Welfare and Food Together • 'Royal ex-bats' grace palace gardens • Celeb sCoop with Songs of Praise presenter JB • Hensus 2017 - The Results! • Gallery - Competitions - Calendar 2018 Inside this issue P6 Eggy News Your chance to win a copy of Jamie Oliver’s new book P8 600,000 saved hens? Yep, that's right! Read about our last 12 years in numbers P12 Hensus results Here's what you told us about your girls in Hensus 2017 (prepare to laugh and cry) P17 Let's talk about AI We put your questions to Chief Veterinary Officer Nigel Gibbens P20 Competition time! A gorgeous clutch of prize-winning pies perfect for autumn P21 Who ate all the pies (yep, pies again)?! Higgidy tell us the secrets behind their wholesome products P28 Celeb sCoop New Songs of Praise presenter and ex-pop star JB talks turkeys, ex-bats and French toast P32 Get baking! Got eggs galore? Use them to make these awesome autumn treats P44 Gaynor’s Tips Hens bird brained? We don't think so... P52 Crazy cupcakes See some of this year's best British Hen Welfare Day creations Contact Us British Hen Welfare Trust Hen Nutrition Queries? Hope Chapel, Rose Ash BHWT Careline South Molton Tel: 01362 822904 Devon, EX36 4RF Email: bhwtcareline@ smallholderfeed.co.ukChicken & Egg. Welfare and Food Together. Tel: 01884 860084 Email: [email protected] Company No: 8057493 Web: www.bhwt.org.uk Registered Charity No: 1147356 Chicken & Egg. Welfare and Food Together. 3 Dear Supporters Every now and again I make myself stop, pause for a moment, and reflect on where the charity is in its development. -

David Willan Fresh Food Product List

Product Range Meat & Fish Beef Steaks & Portions 1000406 St. George Barrel Fillet Steaks X KILO 1000916 Highland Reserve Scottish Sirloin X KILO Steaks 1000915 Highland Reserve Scottish Fillet X KILO 1000026 T-Bone Steaks X KILO Steaks 1000325 Fillet Steaks X KILO 1000468 Fillet Tails X KILO 1000024 Sirloin Steaks X KILO 1000025 Rump Steaks X KILO 1000029 Rib Eye Steaks X KILO 1000082 Flat Iron Steaks X KILO 1000027 Top Rump Braising Steaks X KILO 1000345 Chuck Roll Braising Steaks X KILO 1000317 Feather Blade Steaks X KILO 1000028 Sliced Beef Olives X KILO 1000207 Stuffed Beef Olives X KILO 1000501 Sandwich Sirloin Steaks X KILO 1000114 Shin Beef Steaks - bone in X KILO 1000392 Shin Beef Steaks - boneless X KILO 1000457 Whole Bistro Rump Fillet X KILO 1000489 Picanha Rump Roasts X KILO 1000455 St. George Sirloin Steaks X KILO 1000467 Bistro Rump Fillet Steaks X KILO 1000283 St. George Prime Rump Steaks X KILO 1000085 Picanha Rump Slices X KILO Beef Joints & Primals 1000002 Whole Bone in Sirloin X KILO 1000904 Highland Reserve Scottish X KILO Striploins 1000903 Highland Reserve Scottish Whole X KILO 1000443 St. George Sirloin Roast X KILO Fillets 1000473 St. George Topside Roast X KILO 1000003 Whole Bone in Rib of Beef X KILO 1000282 Boneless Rib of Beef X KILO 1000295 Whole Boneless Rib Eye X KILO 1000006 Whole Topside X KILO 1000007 Whole Silverside X KILO 1000008 Whole Thick Flank/Top Rump X KILO 1000009 Whole D Rump X KILO 1000410 Whole Beef Fillet (chain off) X KILO 1000010 Whole Beef Fillet (chain on) X KILO 1000011 Rump End Fillet -

Exploring Opportunities in the Chilled Ready Meal Sector in the UK Photo by Nico Smit on Unsplash Brian Kelly PCF Business Development Manager

25th November 2020 Exploring opportunities in the Chilled Ready Meal sector in the UK Photo by Nico Smit on Unsplash Brian Kelly PCF Business Development Manager Bord Bia Team Klara Lynch Insight & Planning Specialist, GB Roisin Keane Market Specialist GB, PCF Expert/ Framing Exploration Industry Validation Futures Engagements We met key We reviewed We spoke with We conducted a Using our members in the existing reports industry and national survey of NEXTWATCH tool Bord Bia Insights and information experts in the food n=1,000 ready we assessed the Team to related to Ready industry to meal buyers to get potential for a understand and Meals to understand their a deep number of have clear incorporate this in view and collect understanding of emerging “futures” requirements for our initial point of potential trends in the dynamics from the research the project. analysis. the future. within the sector Step 1 Step 2 Step 3 Step 4 Step 5 Photo by Osman Rana on Unsplash This project provides you with an in depth assessment of the Chilled Ready Meals sector in the UK. We will explore the following areas today: Category Dynamics Shopper Behaviours Triggers and Barriers to Purchase Trends and Evolving Needs Futures and Innovation Photo by Jonatan Pie on Unsplash 6 Innovate or Die Innovation is part and parcel of a category fuelled by trends and characterised by variety. It is essential that producers and ingredient supplier stay ahead of the game. It is estimated that more than 70% of innovation is retailer driven in response to spec requests and seasonal strategies and thematic initiatives (e.g.