Explaining the Flows of Silver in and out of China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qing (Manchu) Dynasty 1644 -1910

5/3/2012 Qing (Manchu) Dynasty 1644 -1910 Qing 1644-1910 Qing 1644-1910 Qing Dynasty (1644 - 1912) Ming dynasty fell in 1644 amid peasant uprisings and Manchu invasion Manchu and Han Chinese 1 5/3/2012 Politics Manchus rule - not Han Chinese strongly resisted by native Han Chinese 2 % of the pop. of China was Manchu Manchus ruled using Chinese system but Chinese were forbidden to hold high national offices. Continued Confucian civil service system. The Neo-Confucian philosophy - obedience of subject to ruler continued Qing 1644-1910 Manchu Qing expansion conquered Outer Mongolia and into central Asia, Taiwan and Tibet. First dynasty to eliminate all danger to China from across its land borders. Largest land area of any Chinese state Qing 1644-1910 Qing 1644-1910 2 5/3/2012 Economy Built large public buildings and public irrigation, walls, gates and other infrastructure. Light taxes to win popularity with people Commerce and international trade grew enormously especially with Japan and Europe Exported porcelain, Silk and spices through maritime trade and Silk Road Qing 1644-1910 Religion Neo-Confucianism important Buddhism, Taoism and ancestor worship continue Christianity grew rapidly until the outlawing of Christianity in the 1830s-40s Catholic and Protestant missionaries built churches and spread education throughout rural and urban China Qing 1644-1910 Social Han Chinese discriminated against all Han men to wear their hair braided in the back, which they found humiliating forbid women to bind their feet but repealed the rule in 1688 since they couldn't enforce it Manchus were forbidden to engage in trade or manual labor. -

Rome and China Oxford Studies in Early Empires

ROME AND CHINA OXFORD STUDIES IN EARLY EMPIRES Series Editors Nicola Di Cosmo, Mark Edward Lewis, and Walter Scheidel The Dynamics of Ancient Empires: State Power from Assyria to Byzantium Edited by Ian Morris and Walter Scheidel Rome and China: Comparative Perspectives on Ancient World Empires Edited by Walter Scheidel Rome and China Comparative Perspectives on Ancient World Empires Edited by Walter Scheidel 1 2009 1 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offi ces in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright © 2009 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rome and China : comparative perspectives on ancient world empires / edited by Walter Scheidel. p. cm.—(Oxford studies in early empires) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-533690-0 1. History, Ancient—Historiography. 2. History—Methodology. 3. Rome—History— Republic, 265–30 b.c. -

Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881

China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 The East India Company’s steamship Nemesis and other British ships engaging Chinese junks in the Second Battle of Chuenpi, 7 January 1841, during the first opium war. (British Library) ABOUT THE ARCHIVE China and the Modern World: Imperial China and the West Part I, 1815–1881 is digitised from the FO 17 series of British Foreign Office Files—Foreign Office: Political and Other Departments: General Correspondence before 1906, China— held at the National Archives, UK, providing a vast and significant primary source for researching every aspect of Chinese-British relations during the nineteenth century, ranging from diplomacy to trade, economics, politics, warfare, emigration, translation and law. This first part includes all content from FO 17 volumes 1–872. Source Library Number of Images The National Archives, UK Approximately 532,000 CONTENT From Lord Amherst’s mission at the start of the nineteenth century, through the trading monopoly of the Canton System, and the Opium Wars of 1839–1842 and 1856–1860, Britain and other foreign powers gradually gained commercial, legal, and territorial rights in China. Imperial China and the West provides correspondence from the Factories of Canton (modern Guangzhou) and from the missionaries and diplomats who entered China in the early nineteenth century, as well as from the envoys and missions sent to China from Britain and the later legation and consulates. The documents comprising this collection include communications to and from the British legation, first at Hong Kong and later at Peking, and British consuls at Shanghai, Amoy (Xiamen), Swatow (Shantou), Hankow (Hankou), Newchwang (Yingkou), Chefoo (Yantai), Formosa (Taiwan), and more. -

A Chinese Opinion on Leprosy, Being a Tpanslation of A

A CHINESE OPINION ON LEPROSY, BEINGA TPANSLATIONOF A CHAPTERFROM THE MEDICALSTANDARD-WORK Imperial edition of the Golden Mirror for the medical class1) BY B. A. J. VAN WETTUM. ' LEPROSY. Leprosy always takes its origin from pestilential miasms. Its causes are three in number, and five injurious forms are distinguished. Also five forms with mortification of some part, which make it a most loathsome disease. By self-restraint in the first stage of his illness, the patient may perhaps preserve his COMMENTARY. The ancient name of this disease was - (pestilential "wind") This", JI, means "wind with poison in it". 1) First chapter of the 87tb volume. It was published in the 7th year of the reign of K'ien-Lung,A.D. 1742. According to Wylie, it is one of the best works of moderntimes for general medicalinformation. (A Wylie, Notes on Chineseliterature, pag. 82). It bas a 2) The. above forms the text of the essay. the shape of $ (rhyme) and consistsof four lines each of seven words. In the arrangementof these, not much care is taken with to and regard 2fi: fà (rhytm) flfi (rhyme). 3) The true meaningof the character as occurringin the present essay,is not 257 The Canon 4) says: "this If. means that the blood and the vital ' ' fluid are hot and spoiled". The vital fluid is no longer pure. That is the reason why the nosebone gets injured, the color of the face destroyed and the skin is covered with boils and sores. A poisonous wind has stationed itself in the veins and does not go away. -

Making the Palace Machine Work Palace Machine the Making

11 ASIAN HISTORY Siebert, (eds) & Ko Chen Making the Machine Palace Work Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Making the Palace Machine Work Asian History The aim of the series is to offer a forum for writers of monographs and occasionally anthologies on Asian history. The series focuses on cultural and historical studies of politics and intellectual ideas and crosscuts the disciplines of history, political science, sociology and cultural studies. Series Editor Hans Hågerdal, Linnaeus University, Sweden Editorial Board Roger Greatrex, Lund University David Henley, Leiden University Ariel Lopez, University of the Philippines Angela Schottenhammer, University of Salzburg Deborah Sutton, Lancaster University Making the Palace Machine Work Mobilizing People, Objects, and Nature in the Qing Empire Edited by Martina Siebert, Kai Jun Chen, and Dorothy Ko Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Artful adaptation of a section of the 1750 Complete Map of Beijing of the Qianlong Era (Qianlong Beijing quantu 乾隆北京全圖) showing the Imperial Household Department by Martina Siebert based on the digital copy from the Digital Silk Road project (http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802, vol. 8, leaf 7) Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6372 035 9 e-isbn 978 90 4855 322 8 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789463720359 nur 692 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) The authors / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2021 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). -

Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham

Victorianizing Guangxu: Arresting Flows, Minting Coins, and Exerting Authority in Early Twentieth-Century Kham Scott Relyea, Appalachian State University Abstract In the late Qing and early Republican eras, eastern Tibet (Kham) was a borderland on the cusp of political and economic change. Straddling Sichuan Province and central Tibet, it was coveted by both Chengdu and Lhasa. Informed by an absolutist conception of territorial sovereignty, Sichuan officials sought to exert exclusive authority in Kham by severing its inhabitants from regional and local influence. The resulting efforts to arrest the flow of rupees from British India and the flow of cultural identity entwined with Buddhism from Lhasa were grounded in two misperceptions: that Khampa opposition to Chinese rule was external, fostered solely by local monasteries as conduits of Lhasa’s spiritual authority, and that Sichuan could arrest such influence, the absence of which would legitimize both exclusive authority in Kham and regional assertions of sovereignty. The intersection of these misperceptions with the significance of Buddhism in Khampa identity determined the success of Sichuan’s policies and the focus of this article, the minting and circulation of the first and only Qing coin emblazoned with an image of the emperor. It was a flawed axiom of state and nation builders throughout the world that severing local cultural or spiritual influence was possible—or even necessary—to effect a borderland’s incorporation. Keywords: Sichuan, southwest China, Tibet, currency, Indian rupee, territorial sovereignty, Qing borderlands On December 24, 1904, after an arduous fourteen-week journey along the southern road linking Chengdu with Lhasa, recently appointed assistant amban (Imperial Resident) to Tibet Fengquan reached Batang, a lush green valley at the western edge of Sichuan on the province’s border with central Tibet. -

The Legacies of Forced Freedom: China's Treaty Ports*

The Legacies of Forced Freedom: China’sTreaty Ports Ruixue Jia IIES, Stockholm University January 20, 2011 Abstract Treaty ports in China provide a quasi-natural experiment to study whether and why history matters. This paper focuses on a selected sample of prefectures and shows that treaty ports grew about 20% faster than similar places during 1776-1953 and also enjoyed faster urbanization growth. However, the advantage of treaty ports was very much restricted between 1949 and 1978. After the economic reforms in the 1980s, the places with treaty ports took much better advantage of the opening. The paper also demonstrates that human capital and social norms play a more important role in this context than geography and tangible institutions. JEL code: N15, N35, N95, O11, O18 Contact: [email protected]. I am indebted to Torsten Persson for his guidance from the very early stages of this paper. I thank Abhijit Banerjee, Davide Cantoni, Camilo Garcia, Edward Glaeser, Avner Greif, Richard Hornbeck, Masayuki Kudamatsu, Pinghan Liang, Nathan Nunn, Dwight Perkins, Nancy Qian, James Robinson, David Strömberg, Noam Yuchtman and participants at UPF Economic History Seminar, Econometric Society World Congress 2010, MIT Political Economy Breakfast and Harvard Development Lunch for their comments. I would also like to thank Peter Bol, Shuji Cao, Clifton Pannell and Elizabeth Perry for their discussion of the historical background. Any remaining mistakes are mine. 1 1 Introduction This paper studies the treaty ports system in the history of China and at- tempts to answer two basic questions in the broad literature of history and development: whether history matters and why.1 China’s treaty ports pro- vide an interesting context for studying both questions. -

Table 11 Unequal Treaties Treaty Year Country Stipulations Nanjing 1842 United Kingdom (UK) 5 Free Trade Ports, 1

Table 11 Unequal Treaties Treaty Year Country Stipulations Nanjing 1842 United Kingdom (UK) 5 free trade ports, 1. An indemnity of $21 million: $12 million for military expenses, $6 million for the destroyed opium, and $3 million for the repayment of the hong merchants’ debts to British traders. 2. Abolition of the Co-hong monopolistic system of trade. 3. Opening of five ports to trade and residence of British consuls and merchants and their families: Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo, and Shanghai. 4. Cession of Hong Kong 5. Equality in official correspondence. 6. A fixed tariff, to be established shortly afterwards Bogue 1843 UK money further elaboration treaty of Nanjing the British the right to anchor warships in the treaty ports, but also establishing the principles of extraterritoriality and most-favoured-nation status. Wangxia 1844 USA 'most favoured-nation' Whampoa 1844 France 'most favoured-nation' Canton 1847 Sweden, Norway 'most favoured-nation' not signed by Chinese government Kulja 1851 Russia opening Kulja and Chuguchak to Sino-Russian trade Aigun 1858 Russia Boundary changes river Amur + 'most favoured-nation' Tianjin 1858 France, UK , Russia, USA 10 extra free trade ports Peking 1860 UK, France, Russia Kowloon treaties to UK, Outer Manchuria Russia Tianjin 1861 Prussian Zollverein Free trade Chefoo 1876 UK Tibet Tianjin 1885 France Free trade Peking 1887 Portugal Macau Shimonoseki 1895 Japan independence Korea, area in Liaodong, Taiwan Li-Lobanov 1896 Russia Railroad Hong Kong 1898 UK Hong Kong Kwanchowwan 1899 France a small enclave on the southern coast of China leased for 99 years Boxerprotocol 1901 UK., U.S., Japan, Russia et all Concessions, payments, railroad police Moscow 1907 Russia, Japan Signed 2 treaties, 1 public and 1 secret. -

340336 1 En Bookbackmatter 251..302

A List of Historical Texts 《安禄山事迹》 《楚辭 Á 招魂》 《楚辭注》 《打馬》 《打馬格》 《打馬錄》 《打馬圖經》 《打馬圖示》 《打馬圖序》 《大錢圖錄》 《道教援神契》 《冬月洛城北謁玄元皇帝廟》 《風俗通義 Á 正失》 《佛说七千佛神符經》 《宮詞》 《古博經》 《古今圖書集成》 《古泉匯》 《古事記》 《韓非子 Á 外儲說左上》 《韓非子》 《漢書 Á 武帝記》 《漢書 Á 遊俠傳》 《和漢古今泉貨鑒》 《後漢書 Á 許升婁傳》 《黃帝金匱》 《黃神越章》 《江南曲》 《金鑾密记》 《經國集》 《舊唐書 Á 玄宗本紀》 《舊唐書 Á 職官志 Á 三平准令條》 《開元別記》 © Springer Science+Business Media Singapore 2016 251 A.C. Fang and F. Thierry (eds.), The Language and Iconography of Chinese Charms, DOI 10.1007/978-981-10-1793-3 252 A List of Historical Texts 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷二 Á 戲擲金錢》 《開元天寶遺事 Á 卷三》 《雷霆咒》 《類編長安志》 《歷代錢譜》 《歷代泉譜》 《歷代神仙通鑑》 《聊斋志異》 《遼史 Á 兵衛志》 《六甲祕祝》 《六甲通靈符》 《六甲陰陽符》 《論語 Á 陽貨》 《曲江對雨》 《全唐詩 Á 卷八七五 Á 司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《泉志 Á 卷十五 Á 厭勝品》 《勸學詩》 《群書類叢》 《日本書紀》 《三教論衡》 《尚書》 《尚書考靈曜》 《神清咒》 《詩經》 《十二真君傳》 《史記 Á 宋微子世家 Á 第八》 《史記 Á 吳王濞列傳》 《事物绀珠》 《漱玉集》 《說苑 Á 正諫篇》 《司馬承禎含象鑒文》 《私教類聚》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十一 Á 志第一百四 Á 輿服三 Á 天子之服 皇太子附 后妃之 服 命婦附》 《宋史 Á 卷一百五十二 Á 志第一百五 Á 輿服四 Á 諸臣服上》 《搜神記》 《太平洞極經》 《太平廣記》 《太平御覽》 《太上感應篇》 《太上咒》 《唐會要 Á 卷八十三 Á 嫁娶 Á 建中元年十一月十六日條》 《唐兩京城坊考 Á 卷三》 《唐六典 Á 卷二十 Á 左藏令務》 《天曹地府祭》 A List of Historical Texts 253 《天罡咒》 《通志》 《圖畫見聞志》 《退宮人》 《萬葉集》 《倭名类聚抄》 《五代會要 Á 卷二十九》 《五行大義》 《西京雜記 Á 卷下 Á 陸博術》 《仙人篇》 《新唐書 Á 食貨志》 《新撰陰陽書》 《續錢譜》 《續日本記》 《續資治通鑑》 《延喜式》 《顏氏家訓 Á 雜藝》 《鹽鐵論 Á 授時》 《易經 Á 泰》 《弈旨》 《玉芝堂談薈》 《元史 Á 卷七十八 Á 志第二十八 Á 輿服一 儀衛附》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 符圖部》 《雲笈七籖 Á 卷七 Á 三洞經教部》 《韻府帬玉》 《戰國策 Á 齊策》 《直齋書錄解題》 《周易》 《莊子 Á 天地》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二百一十六 Á 唐紀三十二 Á 玄宗八載》 《資治通鑒 Á 卷二一六 Á 唐天寶十載》 A Chronology of Chinese Dynasties and Periods ca. -

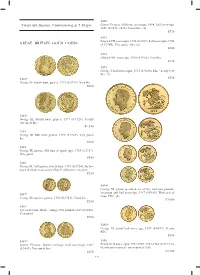

Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 Pm GREAT BRITAIN GOLD

5490 Twentieth Session, Commencing at 7.30 pm Queen Victoria, old head, sovereign, 1898; half sovereign, 1896 (S.3874, 3878). Good fi ne. (2) $570 5491 Edward VII, sovereigns, 1905 (S.3969); half sovereigns, 1908 GREAT BRITAIN GOLD COINS (S.3974B). Very good - fi ne. (2) $500 5492 Edward VII, sovereign, 1910 (S.3969). Very fi ne. $370 5493 George V, half sovereigns, 1912 (S.4006). Fine - nearly very fi ne. (2) $350 5482* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1774 (S.3728). Very fi ne. $600 5483* George III, fourth bust, guinea, 1777 (S.3728). Nearly extremely fi ne. $1,350 5484 George III, fi fth bust, guinea, 1787 (S.3729). Very good/ fi ne. $500 5485 George III, guinea, fi fth bust of spade type, 1788 (S.3729). Very good. $450 5486 George III, half guinea, fourth bust, 1781 (S.3734). Surface marked (from wear as jewellery?), otherwise very fi ne. $250 5494* George VI, proof specimen set of fi ve and two pounds, sovereign and half sovereign, 1937 (S.PS15). With case of 5487* issue, FDC. (4) George III, quarter guinea, 1762 (S.3741). Good fi ne. $7,000 $250 5488 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, two pounds, 1887 (S.3865). Very good. $700 5495* George VI, proof half sovereign, 1937 (S.4077). Nearly FDC. $850 5489* 5496 Queen Victoria, Jubilee coinage, half sovereign, 1887 Elizabeth II, sovereigns, 1957-1959, 1962-1968 (S.4124, 5). (S.3869). Extremely fi ne. Nearly uncirculated - uncirculated. (10) $250 $3,700 532 5497 Elizabeth II, proof sovereigns, 1979 (S.4204) (2); proof half sovereigns, 1980 (S.4205) (2). -

Indians As French Citizens in Colonial Indochina, 1858-1940 Natasha Pairaudeau

Indians as French Citizens in Colonial Indochina, 1858-1940 by Natasha Pairaudeau A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, University of London School of Oriental and African Studies Department of History June 2009 ProQuest Number: 10672932 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672932 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This study demonstrates how Indians with French citizenship were able through their stay in Indochina to have some say in shaping their position within the French colonial empire, and how in turn they made then' mark on Indochina itself. Known as ‘renouncers’, they gained their citizenship by renoimcing their personal laws in order to to be judged by the French civil code. Mainly residing in Cochinchina, they served primarily as functionaries in the French colonial administration, and spent the early decades of their stay battling to secure recognition of their electoral and civil rights in the colony. Their presence in Indochina in turn had an important influence on the ways in which the peoples of Indochina experienced and assessed French colonialism. -

The Wonderful World of Trade Dollars

The Wonderful World of Trade Dollars Lecture Set #34 Project of the Verdugo Hills Coin Club Photographed by John Cork & Raymond Reingohl Introduction Trade Dollars in this presentation are grouped into 3 categories • True Trade Dollars • It was intended to circulate in remote areas from its minting source • Accepted Trade Dollars • Trade dollar’s value was highly accepted for trading purposes in distant lands • Examples are the Spanish & Mexican 8 Reales and the Maria Theresa Thaler • Controversial Trade Dollars • A generally accepted dollar but mainly minted to circulate in a nation’s colonies • Examples are the Piastre de Commerce and Neu Guinea 5 Marks This is the Schlick Guldengroschen, commonly known as the Joachimstaler because of the large silver deposits found in Bohemia; now in the Czech Republic. The reverse of the prior two coins. Elizabeth I authorized this Crown This British piece created to be used by the East India Company is nicknamed the “Porticullis Crown” because of the iron grating which protected castles from unauthorized entry. Obverse and Reverse of a Low Countries (Netherlands) silver Patagon, also called an “Albertus Taler.” Crown of the United Amsterdam Company 8 reales issued in 1601 to facilitate trade between the Dutch and the rest of Europe. Crown of the United Company of Zeeland, minted at Middleburg in 1602, similar in size to the 8 reales. This Crown is rare and counterfeits have been discovered to deceive the unwary. The Dutch Leeuwendaalder was minted for nearly a century and began as the common trade coin from a combination of all the Dutch companies which fought each other as well as other European powers.