Planning Laws for Urban and Regional Planning in Zimbabwe - a Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mozambique Zambia South Africa Zimbabwe Tanzania

UNITED NATIONS MOZAMBIQUE Geospatial 30°E 35°E 40°E L a k UNITED REPUBLIC OF 10°S e 10°S Chinsali M a l a w TANZANIA Palma i Mocimboa da Praia R ovuma Mueda ^! Lua Mecula pu la ZAMBIA L a Quissanga k e NIASSA N Metangula y CABO DELGADO a Chiconono DEM. REP. OF s a Ancuabe Pemba THE CONGO Lichinga Montepuez Marrupa Chipata MALAWI Maúa Lilongwe Namuno Namapa a ^! gw n Mandimba Memba a io u Vila úr L L Mecubúri Nacala Kabwe Gamito Cuamba Vila Ribáué MecontaMonapo Mossuril Fingoè FurancungoCoutinho ^! Nampula 15°S Vila ^! 15°S Lago de NAMPULA TETE Junqueiro ^! Lusaka ZumboCahora Bassa Murrupula Mogincual K Nametil o afu ezi Namarrói Erego e b Mágoè Tete GiléL am i Z Moatize Milange g Angoche Lugela o Z n l a h m a bez e i ZAMBEZIA Vila n azoe Changara da Moma n M a Lake Chemba Morrumbala Maganja Bindura Guro h Kariba Pebane C Namacurra e Chinhoyi Harare Vila Quelimane u ^! Fontes iq Marondera Mopeia Marromeu b am Inhaminga Velha oz P M úngu Chinde Be ni n è SOFALA t of ManicaChimoio o o o o o o o o o o o o o o o gh ZIMBABWE o Bi Mutare Sussundenga Dondo Gweru Masvingo Beira I NDI A N Bulawayo Chibabava 20°S 20°S Espungabera Nova OCE A N Mambone Gwanda MANICA e Sav Inhassôro Vilanculos Chicualacuala Mabote Mapai INHAMBANE Lim Massinga p o p GAZA o Morrumbene Homoíne Massingir Panda ^! National capital SOUTH Inhambane Administrative capital Polokwane Guijá Inharrime Town, village o Chibuto Major airport Magude MaciaManjacazeQuissico International boundary AFRICA Administrative boundary MAPUTO Xai-Xai 25°S Nelspruit Main road 25°S Moamba Manhiça Railway Pretoria MatolaMaputo ^! ^! 0 100 200km Mbabane^!Namaacha Boane 0 50 100mi !\ Bela Johannesburg Lobamba Vista ESWATINI Map No. -

Zimbabwean Government Gazette

A I SET ZIMBABWEAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Published by Authority Vol. LXXI, No. 44 2nd JULY. 1993 Price $2,50 i General Notice 384 of 1993. Zimbabwe United Passenger Company. ^^0/226/93. Permit: 15723. Motor-omnibus. Passenger-capacity: ROAD MOTOR TRANSPORTATION ACT [CHAPTER 262] Route 1: As d^ned in the agreonent between the holder and Applications in Connexion with Road Service Permits the Harare Municipality, approved by the Minister in terms of section 18 of the Road Motor Transportation Act [Chapter 262]. IN terms of subsection (4) of section 7 of the Road Motor Transportation Act [Chapter 262], notice is hereby given that Route 2:' Throu^out Zimbabwe. the applications detailed in the Sdiedule, for ue issue or Route 3: Harare - Darwendale - Banket - Chinhoyi - Aladta amendment of road service permits, have been received for the Compoimd - Sheckleton Mine - lions Den. consideration of the Controller of Road Motor Transportation. Condition: Any person wishing to object to any such application must Route 2: lodge with the Controller of Road Motor Transportation, (a) For private hire and for advertised or organized P.O. Box 8332, Causeway— tours, provided no stage carriage service is operated (a) a notice, in writing, of his intention to object, so as along any route. to reach the Controller’s ofiSce not later than the 23rd (b) No private Hire or any advertised or organized tour July, 1993; shall be operated under authority of this permit, (b) his objection and the grounds therefor, on form RAl.T. during ^e times for which a scheduled stage carriage 24, together with two copies tiiereof, so as to tetaxHa. -

The Spatial Dimension of Socio-Economic Development in Zimbabwe

THE SPATIAL DIMENSION OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT IN ZIMBABWE by EVANS CHAZIRENI Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject GEOGRAPHY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: MRS AC HARMSE NOVEMBER 2003 1 Table of Contents List of figures 7 List of tables 8 Acknowledgements 10 Abstract 11 Chapter 1: Introduction, problem statement and method 1.1 Introduction 12 1.2 Statement of the problem 12 1.3 Objectives of the study 13 1.4 Geography and economic development 14 1.4.1 Economic geography 14 1.4.2 Paradigms in Economic Geography 16 1.4.3 Development paradigms 19 1.5 The spatial economy 21 1.5.1 Unequal development in space 22 1.5.2 The core-periphery model 22 1.5.3 Development strategies 23 1.6 Research design and methodology 26 1.6.1 Objectives of the research 26 1.6.2 Research method 27 1.6.3 Study area 27 1.6.4 Time period 30 1.6.5 Data gathering 30 1.6.6 Data analysis 31 1.7 Organisation of the thesis 32 2 Chapter 2: Spatial Economic development: Theory, Policy and practice 2.1 Introduction 34 2.2. Spatial economic development 34 2.3. Models of spatial economic development 36 2.3.1. The core-periphery model 37 2.3.2 Model of development regions 39 2.3.2.1 Core region 41 2.3.2.2 Upward transitional region 41 2.3.2.3 Resource frontier region 42 2.3.2.4 Downward transitional regions 43 2.3.2.5 Special problem region 44 2.3.3 Application of the model of development regions 44 2.3.3.1 Application of the model in Venezuela 44 2.3.3.2 Application of the model in South Africa 46 2.3.3.3 Application of the model in Swaziland 49 2.4. -

"Our Hands Are Tied" Erosion of the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe – Nov

“Our Hands Are Tied” Erosion of the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe Copyright © 2008 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-56432-404-4 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor New York, NY 10118-3299 USA Tel: +1 212 290 4700, Fax: +1 212 736 1300 [email protected] Poststraße 4-5 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10, Fax: +49 30 2593 0629 [email protected] Avenue des Gaulois, 7 1040 Brussels, Belgium Tel: + 32 (2) 732 2009, Fax: + 32 (2) 732 0471 [email protected] 64-66 Rue de Lausanne 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +41 22 738 0481, Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor London N1 9HF, UK Tel: +44 20 7713 1995, Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 [email protected] 27 Rue de Lisbonne 75008 Paris, France Tel: +33 (1)43 59 55 35, Fax: +33 (1) 43 59 55 22 [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Washington, DC 20009 USA Tel: +1 202 612 4321, Fax: +1 202 612 4333 [email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org November 2008 1-56432-404-4 “Our Hands Are Tied” Erosion of the Rule of Law in Zimbabwe I. Summary ............................................................................................................... 1 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................... 5 To the Future Government of Zimbabwe .............................................................. 5 To the Chief Justice ............................................................................................ 6 To the Office of the Attorney General .................................................................. 6 To the Commissioner General of the Zimbabwe Republic Police .......................... 6 To the Southern African Development Community and the African Union ........... -

Status of Telecommunications Sector in Zimbabwe

TELECOMMUNICATIONS STATUS IN ZIMBABWE Sirewu Baxton [email protected] Background • Postal and Telecommunications Regulatory Authority of Zimbabwe (POTRAZ) o Established by the Postal and Telecommunications Act of 2000. o Started its operations in March 2001 o POTRAZ situated at Emerald Business Park, No. 30 The Chase Harare • Legislation brought about a new institutional framework for telecommunications: o Liberalized the sector o Introduced distinct roles of government, regulator, operators, and consumers. POTRAZ MANDATE • Ensuring provision of sufficient domestic and international telecommunication services • Ensuring provision of services at rates consistent with the provision of an efficient and continuous service • Promote the development of the sector services in accordance with: o Practicable recognised international standards o Public demand POTRAZ MANDATE cont’d • Furthers the advancement of technology • Represents Zimbabwe internationally in matters relating to the sector • Establishes, approves or controls the National Numbering plan • Manages the Radio Frequency Resource • Advises the Government on all matters relating to the telecommunication services General Country Background Location Southern Africa Area 390 590 square Km Population 12.6 Million Population Distribution 38% Urban: 62% Rural • Telecommunication service usage is mainly in urban areas. MARKET STRUCTURE FIXED • One fixed public operator (TelOne.) • Offers local, regional and international voice telephone services. • Has 337 881 subscribers (Lines) • The fixed teledensity is 2.68%. • Of these, 61 % are in the capital Harare. • 53% are residential lines. • 84 % of the lines are connected to the digital exchange. • 17 % of the lines are in rural areas. MARKET STRUCTURE MOBILE • There are three mobile operators: Econet, Net One and Telecel • The current subscriber base as at 30 June 2011 for the operators: Econet 5,521,000 Telecel 1,297,000 Net One 1,349,000 • Mobile teledensity stands at 64.85 %. -

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Basemap

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Basemap Mashonaland Central Karanda Chimandau Guruve MukosaMukosa Guruve Kamusasa Karanda Marymount Matsvitsi Marymount Mary Mount Locations ShinjeShinje Horseshoe Nyamahobobo Ruyamuro RUSHINGA CentenaryDavid Nelson Nyamatikiti Nyamatikiti Province Capital Nyakapupu M a z o w e CENTENARY Mazowe St. Pius MOUNT DARWIN 2 Chipuriro Mount DarwinZRP NyanzouNyanzou Mt Darwin Chidikamwedzi Town 17 GoromonziNyahuku Tsakare GURUVE Jingamvura MAKONDE Kafura Nyamhondoro Place of Local Importance Bepura 40 Kafura Mugarakamwe Mudindo Nyamanyora Chingamuka Bure Katanya Nyamanyora Bare Chihuri Dindi ARDA Sisi Manga Dindi Goora Mission M u s e n g e z i Nyakasoro KondoKondo Zvomanyanga Goora Wa l t o n Chinehasha Madziwa Chitsungo Mine Silverside Donje Madombwe Mutepatepa Nyamaruro C o w l e y Chistungo Chisvo DenderaDendera Nyamapanda Birkdale Chimukoko Nyamapanda Chindunduma 13 Mukodzongi UMFURUDZI SAFARI AREA Madziwa Chiunye KotwaKotwa 16 Chiunye Shinga Health Facility Nyakudya UZUMBA MARAMBA PFUNGWE Shinga Kotwa Nyakudya Bradley Institute Borera Kapotesa Shopo ChakondaTakawira MvurwiMvurwi Makope Raffingora Jester H y d e Maramba Ayrshire Madziwa Raffingora Mvurwi Farm Health Scheme Nyamaropa MUDZI Kasimbwi Masarakufa Boundaries Rusununguko Madziva Mine Madziwa Vanad R u y a Madziwa Masarakufa Shutu Nyamukoho P e m b i Nzvimbo M u f u r u d z i Madziva Teacher's College Vanad Nzvimbo Chidembo SHAMVA Masenda National Boundary Feock MutawatawaMutawatawa Mudzi Rosa Muswewenhede Chakonda Suswe Mutorashanga Madimutsa Chiwarira -

Lions Clubs International Club Membership Register

LIONS CLUBS INTERNATIONAL CLUB MEMBERSHIP REGISTER SUMMARY THE CLUBS AND MEMBERSHIP FIGURES REFLECT CHANGES AS OF DECEMBER 2016 MEMBERSHI P CHANGES CLUB CLUB LAST MMR FCL YR TOTAL IDENT CLUB NAME DIST NBR COUNTRY STATUS RPT DATE OB NEW RENST TRANS DROPS NETCG MEMBERS 5739 027873 GABORONE BOTSWANA 412 4 12-2016 69 2 1 0 -15 -12 57 5739 027874 LOBATSE BOTSWANA 412 4 12-2016 23 2 0 0 -3 -1 22 5739 027875 SELEBI PHIKWE BOTSWANA 412 4 02-2016 14 0 0 0 0 0 14 5739 032054 FRANCISTOWN BOTSWANA 412 4 12-2016 36 0 0 0 0 0 36 5739 061138 MOLEPOLOLE BOTSWANA 412 4 08-2015 8 0 0 0 0 0 8 5739 061487 FRANCISTOWN NYANGABGWE BOTSWANA 412 4 11-2016 12 0 0 0 0 0 12 5739 061632 FRANCISTOWN JUBILEE BOTSWANA 412 4 11-2016 8 0 0 0 -1 -1 7 5739 061633 FRANCISTOWN TATI BOTSWANA 412 4 11-2016 7 1 0 0 0 1 8 5739 061772 SELEBI-PHIKWE MOKOMOTO BOTSWANA 412 4 12-2016 27 2 0 0 -1 1 28 5739 067304 TONOTA BOTSWANA 412 4 06-2015 7 0 0 0 0 0 7 5739 116360 MAUN-GREATER BOTSWANA 412 4 12-2016 36 2 0 0 -2 0 36 5739 127318 Serowe Central BOTSWANA 412 4 11-2016 22 2 0 0 -5 -3 19 5743 027886 BULAWAYO ZIMBABWE 412 4 11-2016 12 3 0 0 -3 0 12 5743 027887 BULAWAYO MATOPOS ZIMBABWE 412 4 10-2016 21 0 0 0 0 0 21 5743 027889 CHIREDZI ZIMBABWE 412 4 11-2016 28 2 0 0 -9 -7 21 5743 027896 GWERU ZIMBABWE 412 4 12-2016 16 1 0 0 -1 0 16 5743 027898 NYANGA ZIMBABWE 412 4 10-2016 14 2 0 0 0 2 16 5743 027907 NORA VALLEY L C ZIMBABWE 412 4 11-2016 8 0 0 0 0 0 8 5743 027908 KWE KWE ZIMBABWE 412 4 12-2016 16 0 0 0 0 0 16 5743 027909 REDCLIFF ZIMBABWE 412 4 11-2016 30 4 0 0 -4 0 30 5743 027911 -

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Overview Map 26 October 2009 Legend Province Capital

MASHONALAND EAST PROVINCE - Overview Map 26 October 2009 Legend Province Capital Hunyani Casembi Key Location Chikafa Chidodo Muzeza Musengezi Mine Mushumbi Musengezi Pools Chadereka Mission Mbire Mukumbura Place of Local Importance Hoya Kaitano Kamutsenzere Kamuchikukundu Bwazi Muzarabani Mavhuradonha Village Bakasa St. St. Gunganyama Pachanza Centenary Alberts Alberts Nembire Road Network Kazunga Chawarura Dotito Primary Chironga Rushinga Mount Rushinga Mukosa Guruve Karanda Rusambo Marymount Chimanda Secondary Marymount Shinje Darwin Rusambo Centenary Nyamatikiti Guruve Feeder azowe MashonalandMount M River Goromonzi Darwin Mudindo Dindi Kafura Bure Nyamanyora Railway Line Central Goora Kondo Madombwe Chistungo Mutepatepa Dendera Nyamapanda International Boundary Madziwa Borera Chiunye Kotwa Nyakudya Shinga Bradley Jester Mvurwi Madziwa Vanad Kasimbwi Institute Masarakufa Nzvimbo Madziwa Province Boundary Feock Mutawatawa Mudzi Muswewenhede Chakonda Suswe Mudzi Mutorashanga Charewa Chikwizo Howard District Boundary Nyota Shamva Nyamatawa Gozi Institute Bindura Chindengu Kawere Muriel Katiyo Rwenya Freda & Mont Dor Caesar Nyamuzuwe River Mazowe Rebecca Uzumba Nyamuzuwe Katsande Makaha River Shamva Mudzonga Makosa Trojan Shamva Nyamakope Fambe Glendale BINDURA MarambaKarimbika Sutton Amandas Uzumba All Nakiwa Kapondoro Concession Manhenga Kanyongo Souls Great Muonwe Mutoko PfungweMuswe Dyke Mushimbo Chimsasa Lake/Waterbody Madamombe Jumbo Bosha Nyadiri Avila Makumbe Mutoko Jumbo Mazowe Makumbe Parirewa Nyawa Rutope Conservation Area -

Urban Agriculture in Harare: Between Suspicion and Repression

CITY CASE STUDY HARARE URBAN AGRICULTURE IN HARARE: BETWEEN SUSPICION AND REPRESSION Beacon Mbiba 1. Introduction Harare is the capital, the largest commercial centre, and the seat of political and administrative power in Zimbabwe. The 1998 population of Harare was around 1.9 million inhabitants. The second largest city of Zimbabwe, Bulawayo, has 1 million inhabitants. Harare's history as a modern city dates back to 1890, when it was established as a fort by settler colonialists sponsored by the British South Africa Company. Harare is located on a watershed in the Northeast of what is called the high veld of Zimbabwe. This is a plateau 1500-2000 m above sea level, which stretches from the southwest of the country, encompassing Harare, extends northwest to Chinhoyi City and to the east beyond Marondera. The high veld climate is cool, with annual temperatures in the range of 10-26oC and with an average annual rainfall of 800-1000 mm. The terrain is relatively flat savanna grassland (HCMPA 1985: 9). Table 1: Key Statistics for Zimbabwe and Harare City Zimbabwe Harare Area 390 757 km2 872 km2 Population (1998) 12.2 million 1.9 million Growth rate 3.5% 5% Natural growth rate 3.5% 3.1% Persons / km2 31 2179 Nuclear household 5 4 size Poverty levels 40%1 or 62%2 44%3 Unemployment 45-50% 45-50% Urbanisation levels 40-50% Not applicable Major threats AIDS, unemployment & AIDS, unemployment economic collapse & economic collapse Harare has a sprawling structure dominated by a radial road network with the central business district (CBD) at its core and industrial areas to the east and south. -

Domestic Workers in Zimbabwe KNOW YOUR RIGHTS and OBLIGATIONS

Domestic Workers in Zimbabwe KNOW YOUR RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS An information guide for domestic workers in Zimbabwe 2016 Free copy 1. WHAT IS THE GUIDE ABOUT? 2. BEFORE ACCEPTING A JOB 3. YOUR BASIC RIGHTS AS A HUMAN BEING IN ZIMBABWE 4. YOUR RIGHTS AND OBLIGATIONS AS A DOMESTIC WORKER IN ZIMBABWE 5. WHO CAN HELP? CONTENTS USEFUL CONTACTS FOR DOMESTIC WORKERS 6. SENDING MONEY BACK HOME 7. SAMPLE CONTRACT Employment Contract for Domestic Worker 2 1. WHAT IS THE GUIDE ABOUT ? This information guide is published by the organisations listed on the back cover. Its objective is to provide up-to-date, reliable information to people who are considering working or already working as domestic workers in Zimbabwe The guide provides information on: Ÿ What you should consider before accepting to work as a domestic worker Ÿ Your basic rights as a human being in Zimbabwe Ÿ Your rights and obligations as a domestic worker in Zimbabwe Ÿ Practical information about sending money to your family Each section provides a list of useful numbers of organizations that can help you. 3 2. BEFORE accepting a job Taking your decision: Ÿ Only make your decision on the basis of verified information: do not trust anyone simply on their word; verify information from different people and organizations. Ÿ Compare the income you currently have and the minimum income you can reasonably hope for in the new job. Ÿ Research the standard conditions of work that apply to your position. Ÿ Try to work out all your costs including accommodation, transport to work, food & toiletries, etc to see whether you will be able to save anything. -

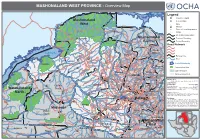

MASHONALAND WEST PROVINCE - Overview Map

MASHONALAND WEST PROVINCE - Overview Map Kanyemba Mana Lake C. Bassa Pools Legend Province Capital Mashonaland Key Location r ive R Mine zi West Hunyani e Paul V Casembi b Chikafa Chidodo Mission Chirundu m Angwa Muzeza a Bridge Z Musengezi Place of Local Importance Rukomechi Masoka Mushumbi Musengezi Mbire Pools Chadereka Village Marongora St. International Boundary Cecelia Makuti Mashonaland Province Boundary Hurungwe Hoya Kaitano Kamuchikukundu Bwazi Chitindiwa Muzarabani District Boundary Shamrocke Bakasa Central St. St. Vuti Alberts Alberts Nembire KARIBA Kachuta Kazunga Chawarura Road Network Charara Lynx Centenary Dotito Kapiri Mwami Guruve Mount Lake Kariba Dora Shinje Masanga Centenary Darwin Doma Mount Maumbe Guruve Gachegache Darwin Railway Line Chalala Tashinga KAROI Kareshi Magunje Bumi Mudindo Bure River Hills Charles Mhangura Nyamhunga Clack Madadzi Goora Mola Mhangura Madombwe Chanetsa Norah Silverside Mutepatepa Bradley Zvipane Chivakanyama Madziwa Lake/Waterbody Kariba Nyakudya Institute Raffingora Jester Mvurwi Vanad Mujere Kapfunde Mudzumu Nzvimbo Shamva Conservation Area Kapfunde Feock Kasimbwi Madziwa Tengwe Siyakobvu Chidamoyo Muswewenhede Chakonda Msapakaruma Chimusimbe Mutorashanga Howard Other Province Negande Chidamoyo Nyota Zave Institute Zvimba Muriel Bindura Siantula Lions Freda & Mashonaland West Den Caesar Rebecca Rukara Mazowe Shamva Marere Shackleton Trojan Shamva Chete CHINHOYI Sutton Amandas Glendale Alaska Alaska BINDURA Banket Muonwe Map Doc Name: Springbok Great Concession Manhenga Tchoda Golden -

Zimbabwe Lean Season Assistance – Januar Y - Apr Il 2021

Zimbabwe Lean Season assistance – Januar y - Apr il 2021 This map aims to represent the level of achievement related to food assistance response for the period Jan-Apr 2021. The selection of the period derives from two major factors: 1) data are available for all actors, and 2) the period coincides with the peak and end of the lean season response plan of major aid agencies. The gradient of the colours shows the ratio of the achievement at district level, calculated considering all beneficiaries reached against the estimation of people in need elaborated in October 2020, and according to the following criteria: People reached:for each agency, it was considered the maximum number of beneficiaries reported in any month. This is because food assistance is supposed to operate by monthly cycle for the same households being served every month of the programme. Both government and non-governmental agencies, including the UN, are included in this map. People in need:it was used the estimation of people in need from the ZimVAC rural assessment, and the WFP CARI report for the urban areas. This choice was made in order to consider all people in need who were supposed to be reached by the implementation of all programmes. Mbire Hurungwe Centenary/ Muzarabani Kariba Urban Mount Rushinga Guruve Darwin Karoi Kariba Bindura Mvurwi Mudzi Mashonaland Shamva Mashonaland West Chinhoyi Bindura Urban UMP East Makonde Mazowe Mutoko Gokwe North Zvimba Goromonzi Harare Binga Harare Murehwa Victoria Chegutu NortonHarare Rural Falls Sanyati Chitungwiza Gokwe Chegutu