The Rule of Law John V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (In a Constitutional Democracy)

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) Imer Flores Georgetown Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-161 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1115 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2156455 Imer Flores, Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy), in LAW, LIBERTY, AND THE RULE OF LAW 77-101 (Imer B. Flores & Kenneth E. Himma eds., Springer Netherlands 2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Chapter6 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) lmer B. Flores Tse-Kung asked, saying "Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one's life?" K'ung1u-tzu said: "Is not reciprocity (i.e. 'shu') such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not ckJ to others." Confucius (2002, XV, 23, 225-226). 6.1 Introduction Taking the "rule of law" seriously implies readdressing and reassessing the claims that relate it to law and liberty, in general, and to a constitutional democracy, in particular. My argument is five-fold and has an addendum which intends to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western civilizations, -

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

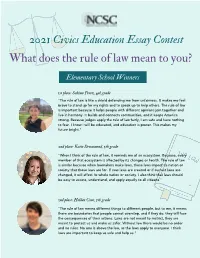

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Rule-Of-Law.Pdf

RULE OF LAW Analyze how landmark Supreme Court decisions maintain the rule of law and protect minorities. About These Resources Rule of law overview Opening questions Discussion questions Case Summaries Express Unpopular Views: Snyder v. Phelps (military funeral protests) Johnson v. Texas (flag burning) Participate in the Judicial Process: Batson v. Kentucky (race and jury selection) J.E.B. v. Alabama (gender and jury selection) Exercise Religious Practices: Church of the Lukumi-Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah (controversial religious practices) Wisconsin v. Yoder (compulsory education law and exercise of religion) Access to Education: Plyer v. Doe (immigrant children) Brown v. Board of Education (separate is not equal) Cooper v. Aaron (implementing desegregation) How to Use These Resources In Advance 1. Teachers/lawyers and students read the case summaries and questions. 2. Participants prepare presentations of the facts and summaries for selected cases in the classroom or courtroom. Examples of presentation methods include lectures, oral arguments, or debates. In the Classroom or Courtroom Teachers/lawyers, and/or judges facilitate the following activities: 1. Presentation: rule of law overview 2. Interactive warm-up: opening discussion 3. Teams of students present: case summaries and discussion questions 4. Wrap-up: questions for understanding Program Times: 50-minute class period; 90-minute courtroom program. Timing depends on the number of cases selected. Presentations maybe made by any combination of teachers, lawyers, and/or students and student teams, followed by the discussion questions included in the wrap-up. Preparation Times: Teachers/Lawyers/Judges: 30 minutes reading Students: 60-90 minutes reading and preparing presentations, depending on the number of cases and the method of presentation selected. -

Rule of Law Freedom Prosperity

George Mason University SCHOOL of LAW The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywick 02-20 LAW AND ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id= The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywicki* After decades of neglect, interest in the nature and consequences of the rule of law has revived in recent years. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered renewed interest in the nature of the rule of law in the Anglo-American tradition. Meanwhile, economists have increasingly come to realize the importance of political and legal institutions, especially the presence of the rule of law, in providing the foundation of freedom and prosperity in developing countries. The emerging economies of Eastern Europe and the developing world in Latin America and Africa have thus sought guidance on how to grow the rule of law in these parts of the world that traditionally have lacked its blessings. This essay summarizes the philosophical and historical foundations of the rule of law, why Bush v. Gore can be understood as a validation of the rule of law, and explores the consequences of the presence or absence of the rule of law in developing countries. I. INTRODUCTION After decades of neglect, the rule of law is much on the minds of legal scholars today. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered a renewed interest in the Anglo-American tradition of the rule of law.1 In the emerging democratic capitalist countries of Eastern Europe, societies have struggled to rediscover the rule of law after decades of Communist tyranny.2 In the developing countries of Latin America, the publication of Hernando de Soto’s brilliant book The Mystery of Capital3 has initiated a fervor of scholarly and political interest in the importance and the challenge of nurturing the rule of law. -

Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law John A

Washington University Jurisprudence Review Volume 9 | Issue 1 2016 Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law John A. Bruegger Follow this and additional works at: http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Theory Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation John A. Bruegger, Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law, 9 Wash. U. Jur. Rev. 081 (2016). Available at: http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Jurisprudence Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREEDOM, LEGALITY, AND THE RULE OF LAW JOHN A. BRUEGGER ABSTRACT There are numerous interactions between the rule of law and the concept of freedom. We can see this by looking at Fuller’s eight principles of legality, the positive and negative theories of liberty, coercive and empowering laws, and the formal and substantive rules of law. Adherence to the rules of formal legality promotes freedom by creating stability and predictability in the law, on which the people can then rely to plan their behaviors around the law—this is freedom under the law. Coercive laws can actually promote negative liberty by pulling people out of a Hobbesian state of nature, and then thereafter can be seen to decrease negative liberty by restricting the behaviors that a person can perform without receiving a sanction. Empowering laws promote negative freedom by creating new legal abilities, which the people can perform. -

A Government of Laws, Not Of

A Government of Laws, Not of Men American Democracy and The Rule of Law Introduction The strength of our democratic institutions relies on the public’s understanding of those institutions. However, we are not preparing Californians with the civic knowledge and skills they need to be active and engaged participants. This white paper is intended to provide concise and accessible context to the understanding of “the rule of law,” and its relevance to the daily lives of individuals. The first of three sections defines the concept of “the rule of law” and provides the historical development from a Western perspective. The second briefly discusses the implementation of “the rule of law” in other countries and jurisdictions, and highlights some of the differences between the United States and countries abroad. While the third underscores the relevance of “the rule of law” to Californians by briefly discussing California’s turbulent past, and modern day advantages to a stable legal system that have helped to create a thriving economy in the great State of California. What is the Rule of Law? The concept of “the rule of law” can be a difficult one to define in specific terms. This section will attempt to assert a general definition of “the rule of law” and provide some context to the development of that definition historically and culturally. Finally, this section covers how “the rule of law” is implemented by the government with a focus on the judicial branch and its interactions with the executive and legislative branches. Overview of the Modern Conception of the Rule of Law A modern view in the United States is that through the separation of powers between the legislative, executive, and judicial branches “that it may be a government of laws and not of men.” 1 This perspective extends to create a system of government where individuals and the government itself are subject to laws that are administered with equity, and neither are subject to 1 Mass. -

Law, Rights, and Other Totemic Illusions: Legal Liberalism and Freud's Theory of the Rule of Law

LAW, RIGHTS, AND OTHER TOTEMIC ILLUSIONS: LEGAL LIBERALISM AND FREUD'S THEORY OF THE RULE OF LAW ROBIN WESTt In the last ten years, a distinctively American jurisprudence has emerged as the dominant liberal theory of law.1 The proponents of this new theory have distinguished it from English legal positivism,2 the old "ruling" liberal theory, by taking seriously what the old theory pur- portedly denied: the autonomous and imperative role of moral rights and principles in legal discourse. Given their serious regard for rights and principles, it is no surprise that the new liberal theorists reject the two definitive claims of legal positivism-that law is the outcome of a positive political procedure and that there exists no necessary connec- tion between law and morality-and endorse instead the natural law- yer's claim that law is both autonomous from politics and essential to the moral progress of civilization.4 These new liberal theo- " Visiting Assistant Professor of Law, Stanford University. B.A. 1976, University of Maryland, Baltimore; J.D. 1979, University of Maryland; J.S.M. 1982, Stanford University. Ronald Dworkin presented a version of this new theory in his 1978 book, Tak- ing Rights Seriously. Dworkin contrasted his theory with legal positivism, which he characterized as the "ruling theory of law." R. DWORKIN, TAKING RIGHTS SERI- OUSLY at vii (1978). English positivism is also widely purported to be a "liberal" the- ory of law. See id. 2 Dworkin is sharply critical of legal positivism, "which holds that the truth of legal propositions consists in facts about the rules that have been adopted by specific social institutions, and in nothing else." Id. -

Montesquieu's Mistakes and the True Meaning of Separation Laurence Claus University of San Diego School of Law, [email protected]

University of San Diego Digital USD University of San Diego Public Law and Legal Law Faculty Scholarship Theory Research Paper Series September 2004 Montesquieu's Mistakes and the True Meaning of Separation Laurence Claus University of San Diego School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digital.sandiego.edu/lwps_public Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legal History Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Public Law and Legal Theory Commons Digital USD Citation Claus, Laurence, "Montesquieu's Mistakes and the True Meaning of Separation" (2004). University of San Diego Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series. 11. http://digital.sandiego.edu/lwps_public/art11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Faculty Scholarship at Digital USD. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of San Diego Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series by an authorized administrator of Digital USD. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claus: Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series September 2004 Montesquieu's Mistakes and the True Meaning of Separation Laurence Claus Published by Digital USD, 2004 1 University of San Diego Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper Series, Art. 11 [2004] MONTESQUIEU’S MISTAKES AND THE TRUE MEANING OF SEPARATION 25 Oxford Journal of Legal Studies (forthcoming) Laurence Claus1 “The political liberty of the subject,” said Montesquieu, “is a tranquility of mind arising from the opinion each person has of his safety. In order to have this liberty, it is requisite the government be so constituted as one man needs not be afraid of another.”2 The liberty of which Montesquieu spoke is directly promoted by apportioning power among political actors in a way that minimizes opportunities for those actors to determine conclusively the reach of their own powers. -

Rule of Law Index Shows Sustained Negative Slide Toward Weaker Rule of Law Around the World

UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL: 11 March 2020 (3:00 AM EST) RULE OF LAW DECLINING WORLDWIDE FOR THIRD YEAR IN A ROW 2020 WJP Rule of Law Index Shows Sustained Negative Slide Toward Weaker Rule of Law Around the World Fundamental Rights, Constraints on Government Powers, and Absence of Corruption Lead Areas of Greatest Decline in Global Report WASHINGTON, DC (11 March 2020) – The World Justice Project (WJP) today released the WJP Rule of Law Index® 2020, an annual report based on national surveys of more than 130,000 households and 4,000 legal practitioners and experts around the world. The WJP Rule of Law Index measures rule of law performance in 128 countries and jurisdictions across eight primary factors: Constraints on Government Powers, Absence of Corruption, Open Government, Fundamental Rights, Order and Security, Regulatory Enforcement, Civil Justice, and Criminal Justice. The Index is the world’s leading source for original, independent data on the rule of law. Global Trends More countries declined than improved in overall rule of law performance for a third year in a row, continuing a negative slide toward weakening and stagnating rule of law around the world. The majority of countries showing deteriorating rule of law in the 2020 Index also declined in the previous year, demonstrating a persistent downward trend. This was particularly pronounced in the Index factor measuring Constraints on Government Powers. The declines were widespread and seen in all corners of the world. In every region, a majority of countries slipped backward or remained unchanged in their overall rule of law performance since the 2019 WJP Rule of Law Index. -

The Importance of the Rule of Law for a Robust, Functioning Democracy

BRIEFING PAPER #4 Svend Erik Skaaning, Aarhus University & V-Dem Project Manager for Civil liberties The Importance of the Rule of Law for a Robust, Functioning Democracy KEY POINTS: DEFINITIONS: • The Rule of Law is a necessary and • The Rule of Law means that laws are general, defining requisite of Liberal Democracy possible to obey, and fairly applied. • The Rule of Law and Electoral Democracy • Electoral Democracy means that access to political are distinct but empirically reinforcing power is determined by free, fair, and inclusive aspects of governance elections under the condition of freedom of expression and association. • There is no optimal sequence between the Rule of Law and Electoral Democracy and • Liberal Democracy is the combination of electoral both are important for human democracy and adherence to civil liberties, checks development and balances, and the rule of law. According to the United Nations General Assembly, the rule of law and democracy are interlinked and mutually reinforcing, and they belong to a set universal and indivisible core values and principles. Democracy and the rule of law, however, are both essentially contested concepts. There is widespread agreement about their positive value, but there is also significant disagreement about their particular meanings. What is more, the relationship between rule of law and democracy can be conceived in different ways. On the one hand, the rule of law is a defining attribute of Liberal Democracy together with free and fair elections, liberal freedoms (such as freedom of expression, association, and religion), and checks and balances. On the other hand, based on a thinner definition of Electoral Democracy, democracy and the rule of law can be seen as distinct phenomena that are empirically related. -

Neo-Liberal Constitutionalism: Ideology, Government and the Rule of Law

Journal of Politics and Law June, 2008 Neo-Liberal Constitutionalism: Ideology, Government and the Rule of Law Rachel S. Turner Research Institute for Law, Politics and Justice, Keele University Keele, Staffordshire, ST5 5BG, UK E-mail: [email protected] Abstract This article explores the centrality of constitutionalism and the rule of law in neo-liberal ideology. It argues that neo-liberalism is not simply a one-dimensional set of economic ideas directed at promoting the free market, but is an ideology with broader political dimensions. At the core of neo-liberalism is a serious doctrine about politics and the proper role of government. Neo-liberals like F.A. Hayek, Milton Friedman and James Buchanan recognised that in order to have a functioning market order, a corresponding political order is a vital corollary. However, the article points out that a number of contradictions and tensions sit at the heart of the neo-liberal conception of politics: those that exist between freedom and the state, liberty and democracy, and law and legislation. The article suggests that one of the most daunting tasks facing neo-liberal politicians and theorists in the twenty-first century will be to overcome the constitutional ‘ignorance’ of Western democracies and institute a framework of rules, conventions or procedures through which the powers of government can be adequately constrained. Keywords: Neo-liberalism, Constitution, Rechtsstaat, Law, Legislation 1. Introduction Neo-liberalism acknowledges the need for government, but is, at the same time, acutely aware of the dangers that government embodies. The constitution is a fundamental concept for neo-liberalism as it represents the only acceptable means through which the powers of government and other state officials may be curtailed. -

Honor Brabazon (Ed.). Neoliberal Legality: Understanding the Role of Law in the Neoliberal Project

Book Reviews 1071 international levels have sought so much guidance on how to proceed from professionals versed in, and advising on the basis of, international law – guidance that was ignored, confused or dis- missed by the politicians, who nonetheless debated the appropriate course of action by sustained reference to international law, as understood or opportunistically framed by them. It is an object lesson in occupational humility, imparted in modest style. Roger O’Keefe Professor of International Law Bocconi University Email: [email protected] doi:10.1093/ejil/chz053 Honor Brabazon (ed.). Neoliberal Legality: Understanding the Role of Law in the Neoliberal Project. New York: Routledge, 2016. Pp. 214. £93.99. ISBN: 9781138684171 In this book, Honor Brabazon and her co-authors advance the debate on the nature of the re- lationship between law and neoliberalism. Since scholarship on the subject first took off in the early 2000s, considerable attention has been dedicated to tracing the intellectual influences of neoliberal theorists, identifying what is distinctive about the political ideology of neoliberalism and documenting and dissecting neoliberalism’s manifestation as economic policy and practices of governmentality. By now, critical writing on neoliberalism has achieved the status of some- thing like a sub-speciality in the social sciences and humanities. Yet, as Brabazon impresses in her introduction to the volume, ‘the role of law in the neoliberal story has been relatively ne- glected, and the idea of neoliberalism as a juridical project has not been considered’ (at 1).1 Part of the explanation for this scholarly shortcoming may be that, for a number of years, the anti- statist, free market rhetoric of neoliberal politicians was taken at face value by many analysts.