The Rule of Law As a Law of Rules Antonin Scaliat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding the Value of Law Related and Civic Education 34P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 429 879 SO 029 531 AUTHOR Cornett, Jeffrey W. TITLE Understanding the Value of Law Related and Civic Education for Youth: A Review of the Literature. PUB DATE 1998-05-00 NOTE 34p.; Report prepared for the American Bar Association, April 1997. Paper presented at the Civitas: An International Civic Exchange Program Conference (Vogosca-Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, May 7-13, 1998). PUB TYPE Information Analyses (070)=- Speeches/Meeting Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Citizenship Education; *Civics; Critical Thinking; *Law Related Education; Literature Reviews; *Scholarship; Secondary Education; Social Studies; Student Attitudes; Student Behavior IDENTIFIERS Civic Values ABSTRACT Research in law-related education (LRE) and related fields is reviewed in this report. For the past two decades, researchers consistently have reported that law-related curricula and instruction make a positive impact on youth when compared to traditional approaches to teaching and learning law, civics, and government. The overall conclusion is that LRE programs have a positive effect on student knowledgeabout law and legal processes, and individual rights and responsibilities. Inaddition, there is evidence that LRE programs have a positive influence on student attitudes and behavior. The most positive changes in student behavior often are associated with LRE programs where the following elements are present: instruction is of high quality and promotes higher order thinking; students are actively involved in the instructional process; teachers thoughtfully mediate the curriculum through wise selection of materials and outside resource persons; administrators actively support the program; and instructors have a network of professional peer support. This review incorporates an analysis of the major databases that yielded 9 technical reports, 6 scholarly papers, and 25 dissertations directly linked to law-related education. -

The World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law Index® 2020 Board of Directors: Sheikha Abdulla Al-Misnad, Report Was Prepared by the World Justice Project

World Justice .:�=; Project World Justice Project ® Rule of Law Index 2020 The World Justice Project Rule The World Justice Project of Law Index® 2020 The World Justice Project (WJP) Rule of Law Index® 2020 Board of Directors: Sheikha Abdulla Al-Misnad, report was prepared by the World Justice Project. Kamel Ayadi, William C. Hubbard, Hassan Bubacar The Index’s conceptual framework and methodology Jallow, Suet-Fern Lee, Mondli Makhanya, Margaret were developed by Juan Carlos Botero, Mark David McKeown, William H. Neukom, John Nery, Ellen Agrast, and Alejandro Ponce. Data collection and Gracie Northfleet, James R. Silkenat and Petar Stoyanov. analysis for the 2020 report was performed by Lindsey Bock, Erin Campbell, Alicia Evangelides, Emma Frerichs, Directors Emeritus: President Dr. Ashraf Ghani Ahmadzai Joshua Fuller, Amy Gryskiewicz, Camilo Gutiérrez Patiño, Matthew Harman, Alexa Hopkins, Ayyub Officers: Mark D. Agrast, Vice President; Deborah Ibrahim, Sarah Chamness Long, Rachel L. Martin, Jorge Enix-Ross, Vice President; Nancy Ward, Vice A. Morales, Alejandro Ponce, Natalia Rodríguez President; William C. Hubbard, Chairman of the Cajamarca, Leslie Solís Saravia, Rebecca Silvas, and Board; Gerold W. Libby, General Counsel and Adriana Stephan, with the assistance of Claudia Secretary; William H. Neukom, Founder and CEO; Bobadilla, Gabriel Hearn-Desautels, Maura McCrary, James R. Silkenat, Director and Treasurer. Emma Poplack, and Francesca Tinucci. The report was produced under the executive direction of Elizabeth Executive Director: Elizabeth Andersen Andersen. Chief Research Officer: Alejandro Ponce Lead graphic designer for this report was Priyanka Khosla, with assistance from Courtney Babcock. The WJP Rule of Law Index 2020 report was made possible by the generous supporters of the work of the Lead website designer was Pitch Interactive, with World Justice Project listed in this report on page 203. -

EEO Is the Law Poster Supplement

“EEO is the Law” Poster Supplement Employers Holding Federal Contracts or Subcontracts Section Revisions The Executive Order 11246 section is revised as follows: RACE, COLOR, RELIGION, SEX, SEXUAL ORIENTATION, GENDER IDENTITY, NATIONAL ORIGIN Executive Order 11246, as amended, prohibits employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, or national origin, and requires affirmative action to ensure equality of opportunity in all aspects of employment. PAY SECRECY Executive Order 11246, as amended, protects applicants and employees from discrimination based on inquiring about, disclosing, or discussing their compensation or the compensation of other applicants or employees. The Individuals with Disabilities section is revised as follows: INDIVIDUALS WITH DISABILITIES Section 503 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, as amended, protects qualified individuals with disabilities from discrimination in hiring, promotion, discharge, pay, fringe benefits, job training, classification, referral, and other aspects of employment. Disability discrimination includes not making reasonable accommodation to the known physical or mental limitations of an otherwise qualified individual with a disability who is an applicant or employee, barring undue hardship to the employer. Section 503 also requires that Federal contractors take affirmative action to employ and advance in employment qualified individuals with disabilities at all levels of employment, including the executive level. The Vietnam Era, Special Disabled Veterans section is revised as follows: PROTECTED VETERANS The Vietnam Era Veterans’ Readjustment Assistance Act of 1974, as amended, 38 U.S.C. 4212, prohibits employment discrimination against, and requires affirmative action to recruit, employ, and advance in employment, disabled veterans, recently separated veterans (i.e., within three years of discharge or release from active duty), active duty wartime or campaign badge veterans, or Armed Forces service medal veterans. -

The Fundamentals of Constitutional Courts

Constitution Brief April 2017 Summary The Fundamentals of This Constitution Brief provides a basic guide to constitutional courts and the issues that they raise in constitution-building processes, and is Constitutional Courts intended for use by constitution-makers and other democratic actors and stakeholders in Myanmar. Andrew Harding About MyConstitution 1. What are constitutional courts? The MyConstitution project works towards a home-grown and well-informed constitutional A written constitution is generally intended to have specific and legally binding culture as an integral part of democratic transition effects on citizens’ rights and on political processes such as elections and legislative and sustainable peace in Myanmar. Based on procedure. This is not always true: in the People’s Republic of China, for example, demand, expert advisory services are provided it is clear that constitutional rights may not be enforced in courts of law and the to those involved in constitution-building efforts. constitution has only aspirational, not juridical, effects. This series of Constitution Briefs is produced as If a constitution is intended to be binding there must be some means of part of this effort. enforcing it by deciding when an act or decision is contrary to the constitution The MyConstitution project also provides and providing some remedy where this occurs. We call this process ‘constitutional opportunities for learning and dialogue on review’. Constitutions across the world have devised broadly two types of relevant constitutional issues based on the constitutional review, carried out either by a specialized constitutional court or history of Myanmar and comparative experience. by courts of general legal jurisdiction. -

All Mixed up About Mixed Questions

The Journal of Appellate Practice and Process Volume 7 Issue 1 Article 7 2005 All Mixed Up about Mixed Questions Randall H. Warner Follow this and additional works at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/appellatepracticeprocess Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Randall H. Warner, All Mixed Up about Mixed Questions, 7 J. APP. PRAC. & PROCESS 101 (2005). Available at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/appellatepracticeprocess/vol7/iss1/7 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Appellate Practice and Process by an authorized administrator of Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE JOURNAL OF APPELLATE PRACTICE AND PROCESS ARTICLES ALL MIXED UP ABOUT MIXED QUESTIONS* Randall H. Warner** I. INTRODUCTION "Elusive abominations."' Among the countless opinions that wrestle with so-called "mixed questions of law and fact," one from the Court of Claims best summed up the problem with these two words. The Ninth Circuit was more direct, if less poetic, when it said that mixed question jurisprudence "lacks clarity and coherence."2 And as if to punctuate the point, Black's Law Dictionary offers a definition that is perfectly clear and perfectly circular: "A question depending for solution on questions of both law and fact, but is really a question3 of either law or fact to be decided by either judge or jury." * © 2005 Randall H. Warner. All rights reserved. ** The author is an appellate lawyer with the Phoenix firm of Jones, Skelton & Hochuli, PLC. -

Preserving the Record

Chapter Seven: Preserving the Record Edward G. O’Connor, Esquire Patrick R. Kingsley, Esquire Echert Seamans Cherin & Mellot Pittsburgh PRESERVING THE RECORD I. THE IMPORTANCE OF PRESERVING THE RECORD. Evidentiary rulings are seldom the basis for a reversal on appeal. Appellate courts are reluctant to reverse because of an error in admitting or excluding evidence, and sometimes actively search for a way to hold that a claim of error in an evidence ruling is barred. R. Keeton, Trial Tactics and Methods, 191 (1973). It is important, therefore, to preserve the record in the trial court to avoid giving the Appellate Court the opportunity to ignore your claim of error merely because of a technicality. II. PRESERVING THE RECORD WHERE THE TRIAL COURT HAS LET IN YOUR OPPONENT’S EVIDENCE. A. The Need to Object: 1. Preserving the Issue for Appeal. A failure to object to the admission of evidence ordinarily constitutes a waiver of the right to object to the admissibility or use of that evidence. Taylor v. Celotex Corp., 393 Pa. Super. 566, 574 A.2d 1084 (1990). If there is no objection, the court is not obligated to exclude improper evidence being offered. Errors in admitting evidence at trial are usually waived on appeal unless a proper, timely objection was made during the trial. Commonwealth v. Collins, 492 Pa. 405, 424 A.2d 1254 (1981). The rules of appellate procedure are meant to afford the trial judge an opportunity to correct any mistakes that have been made before these mistakes can be a basis of appeal. A litigator will not be allowed to ambush the trial judge by remaining silent at trial and voice an objection to the Appellate Court only after an unfavorable verdict or judgment is reached. -

Theorizing Legal Needs: Towards a Caring Legal System

Theorizing Legal Needs: Towards a Caring Legal System Benjamin Miller A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the MA degree in Political Science School of Political Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Ottawa Ottawa, Canada 2016 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents Abstract...................................................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 7 The Ethics of Care: An Introduction ........................................................................................ 8 Plan of the Work ....................................................................................................................11 Method & Conceptual Framework .........................................................................................12 Practical Value ......................................................................................................................15 Prima Facie Issues ................................................................................................................15 Chapter 1: Legal Needs ............................................................................................................18 -

Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (In a Constitutional Democracy)

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) Imer Flores Georgetown Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-161 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1115 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2156455 Imer Flores, Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy), in LAW, LIBERTY, AND THE RULE OF LAW 77-101 (Imer B. Flores & Kenneth E. Himma eds., Springer Netherlands 2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Chapter6 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) lmer B. Flores Tse-Kung asked, saying "Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one's life?" K'ung1u-tzu said: "Is not reciprocity (i.e. 'shu') such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not ckJ to others." Confucius (2002, XV, 23, 225-226). 6.1 Introduction Taking the "rule of law" seriously implies readdressing and reassessing the claims that relate it to law and liberty, in general, and to a constitutional democracy, in particular. My argument is five-fold and has an addendum which intends to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western civilizations, -

I Am Coming to a Court Hearing, What Do I Need to Know?

Where will my hearing take place? When will the judge make a decision? ISLEISLE OFOF MANMAN The hearing may take place in any of the court- The judge will normally tell you what decision has COURTS OF JUSTICE rooms, which have equipment to record the pro- been reached when all the evidence has been given. ceedings. A written copy of the decision (an ‘order’) will be sent I am coming to a court hearing, to you after the hearing. The order will not set out what do I need to know? HCG07 The judge decides if the hearing will be held either: the reasons for the decision. The judge may tell you Claimant guidance in the Small Claims Procedure • in public – members of the public are allowed to do something, such as pay money to the other to be present at the hearing if there is sufficient party or begin preparing your evidence for trial, as room; or part of the decision. • in private – generally, only the people involved You should carry out the instructions when you are in the case (called the parties), their witnesses told to do so and not wait until the written order ar- and advocates can be present at the hearing. rives. What happens at the hearing? If the judge needs more time to reach a decision you The judge will normally want to hear first from the will be sent a notice telling you the time, date and claimant (the person who started the case, or place the decision will be given. This is called made the application) then the defendant (the per- ‘reserving judgment’. -

![The Constitution of the United States [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2214/the-constitution-of-the-united-states-pdf-432214.webp)

The Constitution of the United States [PDF]

THE CONSTITUTION oftheUnitedStates NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER We the People of the United States, in Order to form a within three Years after the fi rst Meeting of the Congress more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic of the United States, and within every subsequent Term of Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote ten Years, in such Manner as they shall by Law direct. The the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this thirty Thousand, but each State shall have at Least one Constitution for the United States of America. Representative; and until such enumeration shall be made, the State of New Hampshire shall be entitled to chuse three, Massachusetts eight, Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations one, Connecticut fi ve, New-York six, New Jersey four, Pennsylvania eight, Delaware one, Maryland Article.I. six, Virginia ten, North Carolina fi ve, South Carolina fi ve, and Georgia three. SECTION. 1. When vacancies happen in the Representation from any All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a State, the Executive Authority thereof shall issue Writs of Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Sen- Election to fi ll such Vacancies. ate and House of Representatives. The House of Representatives shall chuse their SECTION. 2. Speaker and other Offi cers; and shall have the sole Power of Impeachment. The House of Representatives shall be composed of Mem- bers chosen every second Year by the People of the several SECTION. -

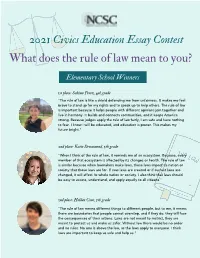

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Rule-Of-Law.Pdf

RULE OF LAW Analyze how landmark Supreme Court decisions maintain the rule of law and protect minorities. About These Resources Rule of law overview Opening questions Discussion questions Case Summaries Express Unpopular Views: Snyder v. Phelps (military funeral protests) Johnson v. Texas (flag burning) Participate in the Judicial Process: Batson v. Kentucky (race and jury selection) J.E.B. v. Alabama (gender and jury selection) Exercise Religious Practices: Church of the Lukumi-Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah (controversial religious practices) Wisconsin v. Yoder (compulsory education law and exercise of religion) Access to Education: Plyer v. Doe (immigrant children) Brown v. Board of Education (separate is not equal) Cooper v. Aaron (implementing desegregation) How to Use These Resources In Advance 1. Teachers/lawyers and students read the case summaries and questions. 2. Participants prepare presentations of the facts and summaries for selected cases in the classroom or courtroom. Examples of presentation methods include lectures, oral arguments, or debates. In the Classroom or Courtroom Teachers/lawyers, and/or judges facilitate the following activities: 1. Presentation: rule of law overview 2. Interactive warm-up: opening discussion 3. Teams of students present: case summaries and discussion questions 4. Wrap-up: questions for understanding Program Times: 50-minute class period; 90-minute courtroom program. Timing depends on the number of cases selected. Presentations maybe made by any combination of teachers, lawyers, and/or students and student teams, followed by the discussion questions included in the wrap-up. Preparation Times: Teachers/Lawyers/Judges: 30 minutes reading Students: 60-90 minutes reading and preparing presentations, depending on the number of cases and the method of presentation selected.