The Rule of Law and the Separation of Powers Denise Meyerson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requir

Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Economics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Gérard Roland, Chair Professor Ernesto Dal Bó Associate Professor Fred Finan Associate Professor Yuriy Gorodnichenko Spring 2018 Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences Copyright 2018 by Weijia Li 1 Abstract Meritocracy in Autocracies: Origins and Consequences by Weijia Li Doctor of Philosophy in Economics University of California, Berkeley Professor Gérard Roland, Chair This dissertation explores how to solve incentive problems in autocracies through institu- tional arrangements centered around political meritocracy. The question is fundamental, as merit-based rewards and promotion of politicians are the cornerstones of key authoritarian regimes such as China. Yet the grave dilemmas in bureaucratic governance are also well recognized. The three essays of the dissertation elaborate on the various solutions to these dilemmas, as well as problems associated with these solutions. Methodologically, the disser- tation utilizes a combination of economic modeling, original data collection, and empirical analysis. The first chapter investigates the puzzle why entrepreneurs invest actively in many autoc- racies where unconstrained politicians may heavily expropriate the entrepreneurs. With a game-theoretical model, I investigate how to constrain politicians through rotation of local politicians and meritocratic evaluation of politicians based on economic growth. The key finding is that, although rotation or merit-based evaluation alone actually makes the holdup problem even worse, it is exactly their combination that can form a credible constraint on politicians to solve the hold-up problem and thus encourages private investment. -

CONSTITUTION of MICHIGAN of 1963 ARTICLE V EXECUTIVE BRANCH § 1 Executive Power

STATE CONSTITUTION (EXCERPT) CONSTITUTION OF MICHIGAN OF 1963 ARTICLE V EXECUTIVE BRANCH § 1 Executive power. Sec. 1. Except to the extent limited or abrogated by article V, section 2, or article IV, section 6, the executive power is vested in the governor. History: Const. 1963, Art. V, § 1, Eff. Jan. 1, 1964;Am. Init., approved Nov. 6, 2018, Eff. Dec. 22, 2018. Compiler's note: The constitutional amendment set out above was submitted to, and approved by, the electors as Proposal 18-2 at the November 6, 2018 general election. This amendment to the Constitution of Michigan of 1963 became effective December 22, 2018. Former constitution: See Const. 1908, Art. VI, § 2. § 2 Principal departments. Sec. 2. All executive and administrative offices, agencies and instrumentalities of the executive branch of state government and their respective functions, powers and duties, except for the office of governor and lieutenant governor, and the governing bodies of institutions of higher education provided for in this constitution, shall be allocated by law among and within not more than 20 principal departments. They shall be grouped as far as practicable according to major purposes. Organization of executive branch; assignment of functions; submission to legislature. Subsequent to the initial allocation, the governor may make changes in the organization of the executive branch or in the assignment of functions among its units which he considers necessary for efficient administration. Where these changes require the force of law, they shall be set forth in executive orders and submitted to the legislature. Thereafter the legislature shall have 60 calendar days of a regular session, or a full regular session if of shorter duration, to disapprove each executive order. -

Presidential Executive Orders: the Bureaucracy, Congress, and the Courts

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2017 Presidential Executive Orders: The Bureaucracy, Congress, and the Courts Michael Edward Thunberg Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Thunberg, Michael Edward, "Presidential Executive Orders: The Bureaucracy, Congress, and the Courts" (2017). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 6808. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/6808 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Presidential Executive Orders: The Bureaucracy, Congress, and the Courts Michael Edward Thunberg Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science Jeff Worsham, Ph.D., Co-Chair John Kilwein, Ph.D., Co-Chair Matthew Jacobsmeier, Ph.D. Dave Hauser, Ph.D. Patrick Hickey, Ph.D. Warren Eller, Ph.D. Department of Political Science Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: President, executive order, unilateral power, institutions, bureaucratic controls, U.S. -

Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: a Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J

American University International Law Review Volume 10 | Issue 4 Article 6 1995 Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation Amy J. Weisman Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/auilr Part of the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Weisman, Amy J. "Separation of Powers in Post-Communist Government: A Constitutional Case Study of the Russian Federation." American University International Law Review 10, no. 4 (1995): 1365-1398. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University International Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEPARATION OF POWERS IN POST- COMMUNIST GOVERNMENT: A CONSTITUTIONAL CASE STUDY OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION Amy J. Weisman* INTRODUCTION This comment explores the myriad of issues related to constructing and maintaining a stable, democratic, and constitutionally based govern- ment in the newly independent Russian Federation. Russia recently adopted a constitution that expresses a dedication to the separation of powers doctrine.' Although this constitution represents a significant step forward in the transition from command economy and one-party rule to market economy and democratic rule, serious violations of the accepted separation of powers doctrine exist. A thorough evaluation of these violations, and indeed, the entire governmental structure of the Russian Federation is necessary to assess its chances for a successful and peace- ful transition and to suggest alternative means for achieving this goal. -

Unit 5 (B) Executive

Parliamentary Democracy in India UNIT 5 (B) EXECUTIVE INTRODUCTION A basic feature that characterizes the Parliamentary model is the presence of dual executives. The President of India is the constitutional head of the state whereas the Prime Minister (PM) and his/her Cabinet are the real executive. The PM and Council of Ministers are chosen from the majority party in the Parliament and are responsible to it for their policies and actions. They remain in office, as long as, they enjoy the confidence of the latter. At the head of the central executive is the President of India. Article 53 of the Constitution formally vests in the President the executive powers of the Union, which are exercised by him/her either directly or through officers subordinate to him/her, in accordance with the Constitution. In practice, he/she is aided and advised by the Cabinet which is headed by the PM. Therefore, the executive at the centre consists of the President, the PM, and Cabinet. In this Unit, we will discuss about political executive at the central level in detail. To begin with, is a discussion on President of India. PRESIDENT The President is a Constitutional head of the State in the sense that he/she represents the nation. All actions of the Government are carried out in his name but he is not the ultimate deciding, directing, or determining factor. Article 52 of the Indian Constitution states ‘there shall be a President of India,’ and, as per Article 53(1) in him/her shall be vested the executive powers of the Union, which are exercised by him/her either directly or through officers subordinate to him in accordance with the Constitution.’ In practice he/she is aided and advised by the Council of Ministers headed by the PM. -

Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (In a Constitutional Democracy)

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2013 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) Imer Flores Georgetown Law Center, [email protected] Georgetown Public Law and Legal Theory Research Paper No. 12-161 This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1115 http://ssrn.com/abstract=2156455 Imer Flores, Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy), in LAW, LIBERTY, AND THE RULE OF LAW 77-101 (Imer B. Flores & Kenneth E. Himma eds., Springer Netherlands 2013) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Jurisprudence Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Chapter6 Law, Liberty and the Rule of Law (in a Constitutional Democracy) lmer B. Flores Tse-Kung asked, saying "Is there one word which may serve as a rule of practice for all one's life?" K'ung1u-tzu said: "Is not reciprocity (i.e. 'shu') such a word? What you do not want done to yourself, do not ckJ to others." Confucius (2002, XV, 23, 225-226). 6.1 Introduction Taking the "rule of law" seriously implies readdressing and reassessing the claims that relate it to law and liberty, in general, and to a constitutional democracy, in particular. My argument is five-fold and has an addendum which intends to bridge the gap between Eastern and Western civilizations, -

Executive Power: the Last Thirty Years

EXECUTIVE POWER: THE LAST THIRTY YEARS GLENN SULMASY* 1. INTRODUCTION The last thirty years have witnessed a continued growth in executive power -with virtually no check by the legislative branch. Regardless of which political party controls the Congress, the institution of the executive continues to grow and increase in power- particularly in the foreign affairs arena. While to many, the end of the Bush administration signaled the end of a perceived "power grab" by the executive branch, nothing could be further from the truth. This short Article will assert that since the founding of this journal thirty years ago, the United States has witnessed several changes that have inevitably led to this rapid expansion of executive power. Section 2 will discuss the Founders' intention that the executive be supreme in the arena of foreign affairs. Section 3 will explore executive power in the twenty-first century, particularly since 9/11 when the vast increases in technology and the ability to inflict massive harm in an instant (often by non-state actors) has necessitated a more aggressive, centralized decisionmaking process within the power of the executive. Additionally, the bureaucratic inefficiencies of the Congress have crippled its ability to actually "check" the executive, for fear of being perceived as "soft on terror" or "weak on defense." With these considerations, this Article recommends that President Barack Obama continue to protect his executive prerogatives as the best means of promoting national security in the twenty-first century. Unfortunately, the real danger is not necessarily the understandable growth in executive power - it is that foreign affairs and wartime decisionmaking is going unchecked by the Congress and is increasingly in the hands of the federal courts and * Glenn Sulmasy is on the law faculty of the United States Coast Guard Academy. -

What Does the Rule of Law Mean to You?

2021 Civics Education Essay Contest What does the rule of law mean to you? Elementary School Winners 1st place: Sabina Perez, 4th grade "The rule of law is like a shield defending me from unfairness. It makes me feel brave to stand up for my rights and to speak up to help others. The rule of law is important because it helps people with different opinions join together and live in harmony. It builds and connects communities, and it keeps America strong. Because judges apply the rule of law fairly, I am safe and have nothing to fear. I know I will be educated, and education is power. This makes my future bright." 2nd place: Katie Drummond, 5th grade "When I think of the rule of law, it reminds me of an ecosystem. Because, every member of that ecosystem is affected by its changes or health. The rule of law is similar because when lawmakers make laws, those laws impact its nation or society that those laws are for. If new laws are created or if current laws are changed, it will affect its whole nation or society. I also think that laws should be easy to access, understand, and apply equally to all citizens." 3nd place: Holden Cone, 5th grade "The rule of law means different things to different people, but to me, it means there are boundaries that people cannot overstep, and if they do, they will face the consequences of their actions. Laws are not meant to restrict, they are meant to protect us and make us safer. -

Rule-Of-Law.Pdf

RULE OF LAW Analyze how landmark Supreme Court decisions maintain the rule of law and protect minorities. About These Resources Rule of law overview Opening questions Discussion questions Case Summaries Express Unpopular Views: Snyder v. Phelps (military funeral protests) Johnson v. Texas (flag burning) Participate in the Judicial Process: Batson v. Kentucky (race and jury selection) J.E.B. v. Alabama (gender and jury selection) Exercise Religious Practices: Church of the Lukumi-Babalu Aye, Inc. v. City of Hialeah (controversial religious practices) Wisconsin v. Yoder (compulsory education law and exercise of religion) Access to Education: Plyer v. Doe (immigrant children) Brown v. Board of Education (separate is not equal) Cooper v. Aaron (implementing desegregation) How to Use These Resources In Advance 1. Teachers/lawyers and students read the case summaries and questions. 2. Participants prepare presentations of the facts and summaries for selected cases in the classroom or courtroom. Examples of presentation methods include lectures, oral arguments, or debates. In the Classroom or Courtroom Teachers/lawyers, and/or judges facilitate the following activities: 1. Presentation: rule of law overview 2. Interactive warm-up: opening discussion 3. Teams of students present: case summaries and discussion questions 4. Wrap-up: questions for understanding Program Times: 50-minute class period; 90-minute courtroom program. Timing depends on the number of cases selected. Presentations maybe made by any combination of teachers, lawyers, and/or students and student teams, followed by the discussion questions included in the wrap-up. Preparation Times: Teachers/Lawyers/Judges: 30 minutes reading Students: 60-90 minutes reading and preparing presentations, depending on the number of cases and the method of presentation selected. -

Rule of Law Freedom Prosperity

George Mason University SCHOOL of LAW The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywick 02-20 LAW AND ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES This paper can be downloaded without charge from the Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection: http://ssrn.com/abstract_id= The Rule of Law, Freedom, and Prosperity Todd J. Zywicki* After decades of neglect, interest in the nature and consequences of the rule of law has revived in recent years. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered renewed interest in the nature of the rule of law in the Anglo-American tradition. Meanwhile, economists have increasingly come to realize the importance of political and legal institutions, especially the presence of the rule of law, in providing the foundation of freedom and prosperity in developing countries. The emerging economies of Eastern Europe and the developing world in Latin America and Africa have thus sought guidance on how to grow the rule of law in these parts of the world that traditionally have lacked its blessings. This essay summarizes the philosophical and historical foundations of the rule of law, why Bush v. Gore can be understood as a validation of the rule of law, and explores the consequences of the presence or absence of the rule of law in developing countries. I. INTRODUCTION After decades of neglect, the rule of law is much on the minds of legal scholars today. In the United States, the Supreme Court’s decision in Bush v. Gore has triggered a renewed interest in the Anglo-American tradition of the rule of law.1 In the emerging democratic capitalist countries of Eastern Europe, societies have struggled to rediscover the rule of law after decades of Communist tyranny.2 In the developing countries of Latin America, the publication of Hernando de Soto’s brilliant book The Mystery of Capital3 has initiated a fervor of scholarly and political interest in the importance and the challenge of nurturing the rule of law. -

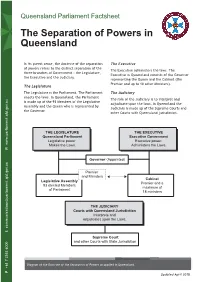

The Separation of Powers in Queensland

Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland In its purest sense, the doctrine of the separation The Executive of powers refers to the distinct separation of the The Executive administers the laws. The three branches of Government - the Legislature, Executive in Queensland consists of the Governor the Executive and the Judiciary. representing the Queen and the Cabinet (the Premier and up to 18 other Ministers). The Legislature The Legislature is the Parliament. The Parliament The Judiciary enacts the laws. In Queensland, the Parliament The role of the Judiciary is to interpret and is made up of the 93 Members of the Legislative adjudicate upon the laws. In Queensland the Assembly and the Queen who is represented by Judiciary is made up of the Supreme Courts and the Governor. other Courts with Queensland jurisdiction. T ST T T Queensland Parliaent eutie oernent eislatie er ecutie er www.parliament.qld.gov.au aes the as dministers the as W Goernor inted Premier and inisters Cainet Leislatie ssel Premier and a elected emers maimum Parliament ministers T ourts with Queensland urisdition nterrets and adudicates un the as E [email protected] E [email protected] Supree ourt and ther urts ith tate urisdictin Diagram of the Doctrine of the Separation of Powers as applied in Queensland. +61 7 3553 6000 P Updated April 2018 Queensland Parliament Factsheet The Separation of Powers in Queensland Theoretically, each branch of government must be separate and not encroach upon the functions of the other branches. Furthermore, the persons who comprise these three branches must be kept separate and distinct. -

Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law John A

Washington University Jurisprudence Review Volume 9 | Issue 1 2016 Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law John A. Bruegger Follow this and additional works at: http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Theory Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation John A. Bruegger, Freedom, Legality, and the Rule of Law, 9 Wash. U. Jur. Rev. 081 (2016). Available at: http://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol9/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Jurisprudence Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FREEDOM, LEGALITY, AND THE RULE OF LAW JOHN A. BRUEGGER ABSTRACT There are numerous interactions between the rule of law and the concept of freedom. We can see this by looking at Fuller’s eight principles of legality, the positive and negative theories of liberty, coercive and empowering laws, and the formal and substantive rules of law. Adherence to the rules of formal legality promotes freedom by creating stability and predictability in the law, on which the people can then rely to plan their behaviors around the law—this is freedom under the law. Coercive laws can actually promote negative liberty by pulling people out of a Hobbesian state of nature, and then thereafter can be seen to decrease negative liberty by restricting the behaviors that a person can perform without receiving a sanction. Empowering laws promote negative freedom by creating new legal abilities, which the people can perform.