Maize in the Philippines. Production Systems, Constraints, And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mindanao-Pricelist-3Rd-Qtr-2020.Pdf

BANK OF COMMERCE ROPA PRICELIST - MINDANAO As of 3RD QTR, 2020 AREA INDICATIVE PROPERTY DESCRIPTION PROPERTY LOCATION TCT / CCT NO. STATUS (SQM) PRICE REGION IX - WESTERN MINDANAO ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR LAND WITH 1-STOREY LOT 1 BLK 3, JOHNSTON ST., BRGY. SAN JOSE GUSU (BRGY. BALIWASAN), T-223,208 820.00 5,063,000.00 RESIDENTIAL & OFFICE BLDG. ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA DE SUR LOT 513, BRGYS. LA PAZ AND PAMUCUTAN, ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA DEL AGRICULTURAL LOT T-217,923 71,424.00 7,143,000.00 SUR LOT 514-B, BRGYS. LA PAZ AND PAMUCUTAN, ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA AGRICULTURAL LOT T-217,924 12,997.00 1,300,000.00 DEL SUR LOT 509-B, BRGYS. LA PAZ AND PAMUCUTAN, ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA AGRICULTURAL LOT T-217,925 20,854.00 2,086,000.00 DEL SUR LOT 512, BRGYS. LA PAZ AND PAMUCUTAN, ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA DEL AGRICULTURAL LOT T-217,926 11,308.00 1,131,000.00 SUR LOT 510, BRGYS. LA PAZ AND PAMUCUTAN, ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA DEL AGRICULTURAL LOT T-217,927 4,690.00 469,000.00 SUR LOT 511, BRGYS. LA PAZ AND PAMUCUTAN, ZAMBOANGA CITY, ZAMBOANGA DEL AGRICULTURAL LOT T-217,928 17,008.00 1,701,000.00 SUR BLK 8, COUNTRY HOMES SUBD., BRGY. AYALA, ZAMBOANGA CITY (SITE IV), RESIDENTIAL VACANT LOT T-217,929 1,703.00 1,022,000.00 ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR BLK 9, COUNTRY HOMES SUBD., BRGY. AYALA, ZAMBOANGA CITY (SITE IV), RESIDENTIAL VACANT LOT T-217,930 1,258.00 755,000.00 ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR BLK 11, COUNTRY HOMES SUBD., BRGY. -

Republic Act No. 10727

H. No. 4631 ^public nf f If E ^IfilippiiiES filnngrBSs uf f{jB pijUxpjixtiBs (MEfr0(:^m b i ^ucfsEttflf (langrEsa ®Iftrh ^gukr(^Ession Begun and Held in Metro Manila, on Monday, the twenty-seventh day of July, two thousand fifteen. [ Republic act N o. 10 72 7 ] AN ACT SEPARATING THE SILAE NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL - ST. PETER ANNEX IN BARANGAY ST. PETER, CITY OF MALAYBALAY. PROVINCE OF BUKIDNON FROM THE SILAE NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL, CONVERTING IT INTO AN INDEPENDENT NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL TO BE KNOWN AS ST. PETER NATIONAL HIGH SCHOOL AND APPROPRIATING FUNDS THEREFOR Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Philippines in Congress assembled:, . , Section l. Tlie Silae National High School — St. Peter Annex in Barangay St. Peter, City of Malaybalay, Province of BuMdnon is hereby separated from the Silae Nationkl High School and converted into an independent national high school to be known as St. Peter National High School. Sec. 2. All personnel, assets, liabilities and records of the Silae National High School — St. Peter Annex are hereby transferred to and absorbed by the St. Peter National High SchooL Sec. 3. The Secretary of Education shall immediately include in the Department's program the operationalization of the St. Peter National High School, the initial funding of which shall be charged against the current year's appropriation of the Silae National High School - St. Peter Annex. Thereafter, the amount necessary for the continued operation of the school shall be included in the annual General Appropriations Act. Sec. 4. The Secretary of Education shall issue such rules and regulations as may be necessary to carry out the purpose of this Act. -

2018 Project Implementation Review (PIR)

2018 Project Implementation Report 2018 Project Implementation Review (PIR) PHL SLM Basic Data ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Overall Ratings ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Development Progress ............................................................................................................................ 4 Implementation Progress ...................................................................................................................... 25 Critical Risk Management ..................................................................................................................... 26 Adjustments ........................................................................................................................................... 27 Ratings and Overall Assessments ........................................................................................................ 28 Gender .................................................................................................................................................. 33 Social and Environmental Standards .................................................................................................... 34 Communicating Impact ......................................................................................................................... -

The-Revenue-Code-Of-Malaybalay

Republic of the Philippines Province of Bukidnon City of Malaybalay * * * Office of the Sangguniang Panlungsod EXCERPT FROM THE MINUTES OF THE 19TH REGULAR SESSION FOR CY 2016 OF THE 7TH SANGGUNIANG PANLUNGSOD OF THE CITY OF MALAYBALAY, BUKIDNON HELD AT THE SP SESSION HALL ON NOVEMBER 29, 2016. PRESENT: Hon. City Councilor Jay Warren R. Pabillaran Hon. City Councilor Lorenzo L. Dinlayan, Jr. Hon. City Councilor Hollis C. Monsanto Hon. City Councilor Rendon P. Sangalang Hon. City Councilor George D. Damasco, Sr. Hon. City Councilor Jaime P. Gellor, Jr., Temporary Presiding Officer Hon. City Councilor Louel M. Tortola Hon. City Councilor Nicolas C. Jurolan Hon. City Councilor Manuel M. Evangelista, Sr. ABSENT: Hon. City Vice Mayor Roland F. Deticio (Official Business) Hon. City Councilor Anthony Canuto G. Barroso (Official Business) Hon. City Councilor Provo B. Antipasado, Jr. (Official Business) Hon. City Councilor Bede Blaise S. Omao (Official Business) --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ORDINANCE NO. 880 Series of 2016 Sponsored by the Committee on Ways and Means Chairman - Hon. Hollis C. Monsanto Members - Hon. Jaime P. Gellor, Jr. - Hon. Louel M. Tortola Chapter One GENERAL PROVISIONS Article 1 TITLE, SCOPE AND DEFINITION OF TERMS Section 1. Title. This ordinance shall be known as the Revenue Code of the City of Malaybalay. Section 2. Scope and Application. This Code shall govern the levy, assessment, and collection of taxes, fees, charges and other impositions within the territorial jurisdiction of this City. 1 Article 2 CONSTRUCTION OF PROVISIONS Section 3. Words and Phrases Not Herein Expressly Defined. Words and phrases embodied in this Code not herein specifically defined shall have the same definitions as found in R.A No. -

From the Uplands of Mindanao © 2019 International Association of Jesuit Business Schools11

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ateneo de Manila University: Journals Online Journal of Management for Global Sustainability Volume 7, Issue 2 (2019): 11–24 From the Uplands of Mindanao © 2019 International Association of Jesuit Business Schools11 FROM THE UPLANDS OF MINDANAO Healing a Fragmented Land and Its People Through an Integral Ecological Approach J. ANDRES F. IGNACIO Institute of Environmental Science for Social Change (ESSC) Ateneo de Manila University, Quezon City, Philippines [email protected] ABSTRACT Upland degradation has been a growing concern in the Philippines in the wake of extensive logging and clearing in the 1970s–1980s. As forests vital to the water supplies of burgeoning communities were depleted, the chances of these areas regenerating were set back by the encroachment of intensive agriculture that extended into the uplands. Genetically modified (GM) corn heavily marketed from the early 2000s onward now dominates the marginal uplands of Northern and Central Mindanao through burning in the dry season, adjacent to remaining forest stands and grasslands. Together with the abuse of the soil in pursuit of economic growth, a parallel exploitation of smallholder corn farmers has fueled this degradation, one that has increasingly pushed upland communities into poverty and debt through the unscrupulous financing of private individuals. This paper thus seeks to bring to the fore, among national and local stakeholders, the gravity and urgency of the socioeconomic, social justice, and land use change crises looming in the uplands of this part of Mindanao. An emphasis on alternative and appropriate forms of livelihood for upland communities is being developed to address land degradation in the form of capacity building in forest and water management, eco-agriculture, and bamboo production, processing, and building, to name a few. -

Mindanao Spatial Strategy/Development Framework (Mss/Df) 2015-2045

National Economic and Development Authority MINDANAO SPATIAL STRATEGY/DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK (MSS/DF) 2015-2045 NEDA Board - Regional Development Committee Mindanao Area Committee ii MINDANAO SPATIAL STRATEGY/DEVELOPMENT FRAMEWORK (MSS/DF) MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIRPERSON For several decades, Mindanao has faced challenges on persistent and pervasive poverty, as well as chronic threats to peace. Fortunately, it has shown a considerable amount of resiliency. Given this backdrop, an integrative framework has been identified as one strategic intervention for Mindanao to achieve and sustain inclusive growth and peace. It is in this context that the role of the NEDA Board-Regional Development Committee-Mindanao becomes crucial and most relevant in the realization of inclusive growth and peace in Mindanao, that has been elusive in the past. I commend the efforts of the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) for initiating the formulation of an Area Spatial Development Framework such as the Mindanao Spatial Strategy/Development Framework (MSS/DF), 2015-2045, that provides the direction that Mindanao shall take, in a more spatially-defined manner, that would accelerate the physical and economic integration and transformation of the island, toward inclusive growth and peace. It does not offer “short-cut solutions” to challenges being faced by Mindanao, but rather, it provides guidance on how Mindanao can strategically harness its potentials and take advantage of opportunities, both internal and external, to sustain its growth. During the formulation and legitimization of this document, the RDCom-Mindanao Area Committee (MAC) did not leave any stone unturned as it made sure that all Mindanao Regions, including the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), have been extensively consulted as evidenced by the endorsements of the respective Regional Development Councils (RDCs)/Regional Economic Development and Planning Board (REDPB) of the ARMM. -

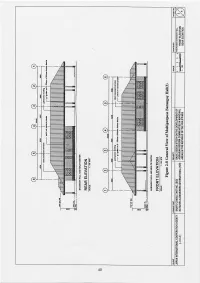

11641115 10.Pdf

22---222---44 Implementation Plan 2-2-4-1 Implementation Policy (1) Outline of Facilities The project components are summarized below. The project sites are located in the Marangog area, Leyte Island and the Silae-Dalacutan area, Mindanao Island. Summary of Project Facilities Construction Silae - Facilities Details Unit Marangog /Rehabilitation Dalacutan Road Newly Conception Bridge No. 1 - construction Access road A Rehabilitation Km 3.84 - Access road B Rehabilitation Km 2.92 - Farm road A Rehabilitation Km - 2.28 Farm road B Rehabilitation Km 3.22 - Dalacutan road Rehabilitation No. - 7 Post-harvest Newly Solar dry yard No. 3 2 construction Newly Ware-house No. 3 2 construction Rural water supply Newly Feeder pipeline m 1,380 2,110 construction Distribution Newly m 3,580 1,340 pipeline construction Newly Faucet No. 12 22 construction Newly Deep well No. - 2 construction Barangay Meeting room, Day Newly multi-purpose hall care center, Health No. 1 1 construction center The Conception Bridge will be built to cross the Salug River (width: about 200 m) with the length of 110.7 m and width of 4.6 m, excluding 90-meter flood release section. The bridge is a submerged type with nine spans of continuous reinforced concrete slab beams, which will be placed in-situ. The type of piers and abutments are concrete piles with 45-cm2 sections, and ten meters of bearing piles will be installed, coping with the geological features of riverbed. All project roads are paved with gravel except for concrete 42 pavement sections that are limited to steep slopes. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BUKIDNON

2010 Census of Population and Housing Bukidnon Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population BUKIDNON 1,299,192 BAUNGON 32,868 Balintad 660 Buenavista 1,072 Danatag 2,585 Kalilangan 883 Lacolac 685 Langaon 1,044 Liboran 3,094 Lingating 4,726 Mabuhay 1,628 Mabunga 1,162 Nicdao 1,938 Imbatug (Pob.) 5,231 Pualas 2,065 Salimbalan 2,915 San Vicente 2,143 San Miguel 1,037 DAMULOG 25,538 Aludas 471 Angga-an 1,320 Tangkulan (Jose Rizal) 2,040 Kinapat 550 Kiraon 586 Kitingting 726 Lagandang 1,060 Macapari 1,255 Maican 989 Migcawayan 1,389 New Compostela 1,066 Old Damulog 1,546 Omonay 4,549 Poblacion (New Damulog) 4,349 Pocopoco 880 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bukidnon Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Sampagar 2,019 San Isidro 743 DANGCAGAN 22,448 Barongcot 2,006 Bugwak 596 Dolorosa 1,015 Kapalaran 1,458 Kianggat 1,527 Lourdes 749 Macarthur 802 Miaray 3,268 Migcuya 1,075 New Visayas 977 Osmeña 1,383 Poblacion 5,782 Sagbayan 1,019 San Vicente 791 DON CARLOS 64,334 Cabadiangan 460 Bocboc 2,668 Buyot 1,038 Calaocalao 2,720 Don Carlos Norte 5,889 Embayao 1,099 Kalubihon 1,207 Kasigkot 1,193 Kawilihan 1,053 Kiara 2,684 Kibatang 2,147 Mahayahay 833 Manlamonay 1,556 Maraymaray 3,593 Mauswagon 1,081 Minsalagan 817 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Bukidnon Total Population by Province, -

R,U,.' Casisan& Malaybalay Gty

Depanment ofEducation J,iE,% Region X-Northern Mindanao DIVISION OF MALAYBALAY CITY r,u,.' Casisan& Malaybalay Gty ---tr|frlog-n-fiK DrvtstoN M EMORANOUM qt DePED-l,4AtAYB,lur (ii /t r/r- , No. 0 s. 2018 RELETISED oare:JA.u1-L4-2lllflrur; ll 24 TO Chief Education Supervisors and Staff- CIO and SGOD EY: *0fu Public/Private Elementary and Secondary School Heads AllOthers Concerned This Division FROM E oPLENARTA, CESO Vr on Superintendent / t DATE: January 24, 2018 SUBJECT: RESULTS OF 2018 METROBANK- MTAP- DEPED MATH CHALLENGE OIVISION ELIMINATION ROUNDS AND SCHOOTS QUALIFIED FOR THE DIVISION TEAM FINALS 1. This Office announces Ure official results ofthe 2018 Metrobank-MTAP-DepEd Math Challenge Divirion Elimination Rounds conducted lastJanuary 18, 2018 foa Elementary levelat the four (4) testng centers: Sumpong CentralS.hool, Malaybalay City Central School, Linabo Central School and Zamboanguita CentralSchool and on January 19, 2018 for the lunior High School level at Malaybalay City National High S.hool, San lose, Malaybalay City. A. Elementary Level: (All schools listed orc quohlied to NfticiNte ih the Division Teom Orol Fittuls. These ore the top 20 Schools) . NO GRAOE 1 6RAOE 2 GRADT 3 GNADE 4 GRADE 5 GRADI6 I BUKSU-ELS MCCS San lsidro MCCS MCCS Saint Johl's CoU Elern School 2 New llocos ES Aghyan CS MCCS BUKSU-ESL Saint John's Malaybalay Schoot City CS 3 Ksla$mgay CS BUKSU-ESL BUKSI,I-ESL BBCA San Isidro Linabo CS Coll€ge-Elern- 4 Zamboeguita San Isidro Belhel Baptist Saint John's Airpon Village San Isidro cs Collese-Etem. -

Teacher Induction Program for Newly Hired Teachers

2o?o- l+ba1 oM 2.o2,o - og- dot 0tPt0 MAt YIILAY clrY ClyJiiJA 6 REI.IA5ED Ei-!J{s-lDr, atrrtlir d ttr pliumtlrr !.1!a DelErtment of Gluation REGION X. NORT}IERN MINDANAO DMSION OF MALAYBAIAY CITY DIVISION MEMORAN'DUM No. Ao1 s. 2020 Assistant Schools Division Superitrtendent Chief Education Supervisors, SGOD and CID Education hogram Supervisors Public Schools District Supervisors All School Heads All Others Concemed This Division F rom ^VICTORI v. GAZO,PhD,CESO V Di SuFrintendent \chools f Date August 7, Subject: TEACHER INDUCTION PROGRAM FOR NEWLY HIRED TEACHERS I . tn line wrth DepEd order No. 43, series 2017 on 7e dcher lnduchon Program Polic, that supports the continuing prolessional development and Fogress of the newly hired teachers based on the principle of lifelong learning and the Department's commitment to the development of new and beginning teachers, this OIIice in coordinatron with the Human Resource Development Section will conduct a Teacher Induction Program for Newly Hired Teachers on August 11-13,2020 at Iniza's Pavillion, Casissng,Malsybslay City. 2. The participants to this program are newly hired Elementary, Junior and Senior High School Teachers ( Enclosure I ) The actiyity mafix and pool of speakers of the activrty is attached for reference ( Enclosure 2 ). 3. Further, in observance to the lnter-Agency Task Force Health Protocol in the conduct of social gatherings, participants are advised to observe physical distancing and wearing of face mask/face shield ftroughout the aclivrty. 4 Meals and Snacks of the participants shalt b€ charged to Human Resource AddressiSayre Hiway, PL,ror 5, Casisao& MalaybalayCty felefar No.: O8E-314-m94j Telephone No.i 088{13-1246 EmailAddr€ss: E A4rIIir ot S? 3!fiilDirur Deprtmert ot @torstiotr REGION X. -

Community Management Plan PHI: Integrated Natural Resources And

Community Management Plan July 2019 PHI: Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project Higaonon Ancestral Domain Prepared by Bukidnon-Higaonon community of Malabalay City, Bukidnon for the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the Asian Development Bank i Abbreviations ADB - Asian Development Bank ADSDPP - Ancestral Domain Sustainable Development and Protection Plan ANR - Assisted Natural Regeneration BUHITAI - Bukidnon Higaonon Tribal Association Incorporated CADC - Certificate of Ancestral Domain Claim CADT - Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title CBPM - Community-Based Protection and Monitoring CMP - Community Management Plan CP - Certification Pre-condition CSC - Certificate of Stewardship Contract DA - Department of Agriculture DENR - Department of Environment and Natural Resources FPIC - Free Prior Inform Consent ICC - Indigenous Cultural Communities INREMP - Integrated Natural Resources and Environmental Management Project IP - Indigenous People IPDF - Indigenous People’s Development Framework IPO - Indigenous People’s Organization IPRA - Indigenous People’s Rights Act IR - Involuntary Resettlement ISF - Integrated Social Forestry LGU - Local Government Unit LRA - Land Registration Authority M&E - Monitoring and Evaluation NCIP - National Commission on Indigenous People NGP - National Greening Program NRM - Natural Resources Management OFW - Overseas Filipino Worker PD - Presidential Decree PDAF - Priority Development Assistance Fund PES - Payment for Ecological Services PO - People’s Organization -

(LSA) in Bukidnon As of October 29, 2020

AGRICULTURAL TRAINING INSTITUTE-REGIONAL TRAINING CENTER X List of Certified Learning Site for Agriculture (LSA) in Bukidnon As of October 29, 2020 DATE NO. CERTIFICATE NUMBER NAME OF FARM SITE COOPERATOR CITY/MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY PROVINCE DISTRICT LOCATION OF FARM DATE ACCREDITTED BY ATI CONTACT NUMBER EMAIL ADDRESS LAND AREA BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF FARM ESTABLISHED There are 8,000 mushroom fruiting bags that provides daily income, native pigs, free-range chickens, different vegetables, and spices. Also, they are growing Purok 8, Kalasungay, numerianoquemado@g 1 LSA-2020-09-198 Mushroom City Numeriano O. Quemado III Malaybalay City Kalasungay Bukidnon 2nd 2019 09-Sep-20 9051033365 1.1 ha several types of trees such as Talisay, Malaybalay City, Bukidnon mail.com Coconut, Pink Trumpet, Yellow Trumpet, Cacao, Rambutan, Durian, and other fruit bearing trees. The 16 hectare farm land is practicing diversified farming. They are growing corn, sugarcane, rice, coconut intercropped with banana, black pepper, Caderao's Integrated P-6, Langcataon, [email protected] 2 LSA-2020-09-197 Antonio C. Caderao Pangantucan Langcataon Bukidnon 4th 1989 09-Sep-20 9555568187 16 ha assorted kind of fruit trees, ginger, and Farm Pangantucan, Bukidnon m cacao. They also engage in free-range chicken production and livestock raising. They are processing coco honey, coco sugar, coco vinegar, and cacao tablea. They acquired the 1.25 hectare farm land last 2015 and planted with sugarcane but the result was not quite good. So they converted it into a diversified and integrated farm. Part of the area was planted with cacao, coconuts, bananas, Payag ni Daday P-8A South Poblacion, [email protected] 3 LSA-2020-09-196 Jesus G.