Analysing Regional Differences of Agricultural Land Use and Land-Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liebenswerteswetzlar

Im Mai 1772 kam Johann Wolfgang Goethe Wartberg Verlag nach Wetzlar und verliebte sich in die jun- ge Charlotte Buff, die aber einem anderen versprochen war. Diese unglückliche Wetz- larer Liebesgeschichte aus Goethes Feder fand Eingang in die Literaturgeschichte – „Die Leiden des jungen Werthers“. Noch heute kann man sich auf den Spuren des Dichters durch die Stadt begeben. Kommen Sie mit auf eine Tour durch Wetz- lar und entdecken Sie den vom Krieg weit- gehend verschont gebliebenen Stadtkern deutsch · english français mit seinen malerischen Fachwerk- und Ba- rockbauten, die über 700 Jahre alte Lahn- brücke, den Dom und vieles andere mehr. In May 1772 Johann Wolfgang Goethe came to Wetzlar and fell in love with the young Charlotte Buff, who was promised to another man, however. This unfortunate love story of Wetzlar written by Goethe found its place in the history of literature – “The sorrows of young Werther”. Still nowadays you can follow the poet’s traces in the town. Join in on a tour through Wetzlar and discover the old town centre with its picturesque half-timbered and Baroque buildings widely unscathed by the war, the over 700-year-old Lahn bridge, the cathedral and a lot more. En mai 1772, Johann Wolfgang Goethe est venu à Wetzlar et s’est épris de la jeune Charlotte Buff qui était toutefois Wetzlar promise à un autre. Cette histoire d’amour malheureuse est entrée dans l’histoire de la littérature par la plume de Goethe avec « Les Souffrances du jeune Werther ». Aujourd’hui encore, on peut suivre les traces du poète à travers la ville. -

How Is the Age of an Anthropogenic Habitat - Calcareous Grasslands - Affecting the Occurrence

How is the age of an anthropogenic habitat - calcareous grasslands - affecting the occurrence of plant species and vegetation composition - a historical, vegetation and habitat ecological analysis Welche Bedeutung hat das Alter eines anthropogenen Lebensraums, der Kalkmagerrasen, für das Vorkommen von Pflanzenarten und die Zusammensetzung der Vegetation - eine kulturhistorische, vegetations- und standortökologische Analyse. DISSERTATION ZUR ERLANGUNG DES DOKTORGRADES DER NATURWISSENSCHAFTEN (DR. RER. NAT.) DER FAKULTÄT FÜR BIOLOGIE UND VORKLINISCHE MEDIZIN DER UNIVERSITÄT REGENSBURG VORGELEGT VON Petr Karlík aus Prag im Jahr 2018 Promotionsgesuch eingereicht am: 13.12.2018 Die Arbeit wurde angeleitet von: Prof. Dr. Peter Poschlod Prüfungsausschuss: Vorsitzender: Prof. Dr. Christoph Reisch Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Peter Poschlod Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Karel Prach Drittprüfer: PD Dr. Jan Oettler 2 Contents Chapter 1 General introduction 5 Chapter 2 History or abiotic filter: which is more important in determining the species composition of calcareous grasslands? 13 Chapter 3 Identifying plant and environmental indicators of ancient and recent calcareous grasslands 31 Chapter 4 Soil seed bank composition reveals the land-use history of calcareous grasslands. 59 Chapter 5 Soil seed banks and aboveground vegetation of a dry grassland in the Bohemian Karst 87 Chapter 6 Perspectives of using knowledge about the history of grasslands in the nature conservation and restoration practice 97 Summary 104 Literature 107 Danksagung 122 3 4 Chapter 1 General introduction Dry grasslands – an extraordinary habitat When we evaluate natural habitats, we often ask why they are valuable from a conservation point of view. Oftentimes we evaluate their species diversity. For individual species, we consider whether they are original or not. -

Conference Book.Pdf

, - % . !" #! $#% &' ( ))" )*&+ International Conference on Loess Deposits as Archives of Environmental Change in the Past YEREVAN, ARMENIA, 1 -22 September, 2019 International Conference on Loess Deposits as Archives of Environmental Change in the Past YEREVAN, ARMENIA, 1 -22 September, 2019 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES OF THE REPU,LIC OF ARMENIA INSTITUTE OF -EOLO-ICAL SCIENCES International Symposium on "Loess Deposits as Archives of Environmental Change in the Past" September 15-22, 2019 Yerevan (Armenia) International Conference on Loess Deposits as Archives of Environmental Change in the Past YEREVAN, ARMENIA, 1 -22 September, 2019 CONFERENCE VENUE The Armenian National Academy of Sciences is easy to reach: 0019 Yerevan, 24 Marshal Baghramyan Avenue. Institute of Geological Sciences Round Hall of the Presidium of the Armenian National Academy of Sciences International Conference on Loess Deposits as Archives of Environmental Change in the Past YEREVAN, ARMENIA, 1 -22 September, 2019 CONFERENCE PROGRAM Sunday , September 15, 2019 18 :00 Icebreaker and Registration Icebreaker will be organized in the evening in the Geological Museum of the Institute of Geological Sciences of NAS RA, Yerevan, 24a Marshal Baghramyan Avenue Montag, September 16, 2019 09:00 - 9:10 Opening and Welcome address by Director of IGS, Dr. Sci. Kh. Meliksetian 09:00 - 9:40 Introduction Dominik Faust & Markus Fuchs 09: 40 – 11:00 Session I – Loess records - Stratigraphy and palaeoenvironmental information Chairperson: Pierre Antoine 09:40 – 10:00 Jary Z. , Krawczyk M., Raczyk J., Skurzy ski J. Abrupt cold and warm events recorded in last glacial loess in Poland and Western Ukraine. 10:00 – 10:20 Pötter St. , Bösken J., Obreht I., Veres D., Hambach U., Scheidt S., Berg S., Klasen N., Lehmkuhl F. -

Borstgrasrasen

Tuexenia 39: 287–308. Göttingen 2019. doi: 10.14471/2019.39.017, available online at www.zobodat.at Pflanzengesellschaft des Jahres 2020: Borstgrasrasen Plant Community of the Year 2020: Mat grassland (Nardus stricta grassland) Angelika Schwabe1, *, Sabine Tischew2, Erwin Bergmeier3, Eckhard Garve4, Werner Härdtle5, Thilo Heinken6, Norbert Hölzel7, Cord Peppler-Lisbach8, Dominique Remy9 & Hartmut Dierschke3 1Technische Universität Darmstadt, Fachbereich Biologie, Schnittspahnstr. 10, 64287 Darmstadt, Germany; 2Hochschule Anhalt, FB Landwirtschaft, Ökotrophologie und Landschaftsentwicklung, Strenzfelder Allee 28, 06406 Bernburg, Germany; 3Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Albrecht-von- Haller Institut für Pflanzenwissenschaften, Abteilung für Vegetationsanalyse und Phytodiversität, Untere Karspüle 2, 37073 Göttingen, Germany; 4Haydnstraße 30, 31157 Sarstedt, Germany; 5Leuphana Universität Lüneburg, Institut für Ökologie, Universitätsallee 1, 21335 Lüneburg, Germany; 6Universität Potsdam, Institut für Biochemie und Biologie, Maulbeerallee 3, 14469 Potsdam, Germany; 7Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Institut für Landschaftsökologie, Heisenbergstr. 2, 48149 Münster, Germany; 8Universität Oldenburg, Institut für Biologie und Umweltwissenschaften, AG Landschaftsökologie, Carl von Ossietzky Str. 9-11, 26129 Oldenburg, Germany;9Universität Osnabrück, FB5, AG Ökologie, Barbarastraße 13, 49076 Osnabrück, Germany *Korrespondierende Autorin, E-Mail: [email protected] Zusammenfassung Wie erstmals 2019 wird auch für das Jahr 2020 -

Magazine of the Friedhelm Loh Group

Issue 02 | 2016 Magazine of the Friedhelm Loh Group EXPERTISE Cooling technology – High-tech from Northern Italy EXPERIENCE Automotive industry – Stahlo fulfils the highest standards COMMITMENT Integration – Results of a pilot project for refugees LOH GROUP LOH LM EDHE I THE FR F NE O I AZ G MA Friedhelm Loh Stiftung & Co. KG Rudolf-Loh-Straße 1 35708 Haiger, Germany Phone +49 2773 924-0 Fax +49 2773 924-3129 E-mail: [email protected] FOCUS EXTREMES XWW00026EN1611 www.friedhelm-loh-group.com 2016 | Top performers Issue 02 EDITORIAL THE COURAGE TO DARE Dear readers, Boldness is a trait of character. An act of will. It enables people to dare to take action, achieve exceptional results and not be de- terred by risks – as so vividly expressed by the word “audacity”. What actually drives people to be bold and to risk going to ex- tremes? Why do athletes, and even engineers for that matter, push things to their limits and beyond? It’s the great, often unparalleled opportunities that present themselves in these moments. The chance to make the impossible possible. To venture forth into un- charted territory, where no one has gone before. This determination is something that we’ve taken to heart at the Friedhelm Loh Group from the very beginning. We wouldn’t be here today if we hadn’t had the boldness to always try new things and take risks. And that this still holds true today is demonstrated by our current investments at our German locations: with 250 million euros among other things, we’re completely realigning Rittal’s pro- DR FRIEDHELM LOH duction landscape here in the region. -

First Report on the Seroprevalence of Neospora Caninum in Goats from the Federal State of Hesse, Germany

Berliner und Münchener Tierärztliche Wochenschrift 130, Heft 11/12 (2017), Seiten 17–22 17 Berl Münch Tierärztl Wochenschr Clinic for Obstetrics, Gynecology and Andrology of Large and Small Animals with DOI 10.2376/000-9366-17017 Veterinary Ambulance, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Justus Liebig University Giessen, Giessen, Germany1 © 2017 Schlütersche Population Medicine Research Program, School of Veterinary Medicine, Verlagsgesellschaft mbH & Co. KG Universidad Nacional, Heredia, Costa Rica2 ISSN 000-9366 Institute of Parasitology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Justus Liebig University Giessen, Giessen, Germany3 Korrespondenzadresse: Rodolfo.A.Villagra-Blanco@vetmed. uni-giessen.de First report on the seroprevalence of Neospora caninum in goats Eingegangen: 09.03.2017 Angenommen: 1.06.2017 from the Federal State of Hesse, Germany Online first: 23.10.2017 http://vetline.de/facharchiv/18/3222 Erster Bericht über die Seroprävalenz von Neospora caninum in hessischen Ziegenbeständen Rodolfo Villagra-Blanco1,2,3, Henrik Wagner1, Gaby Dolz2, Juan José Romero- Zúñiga2, Anja Taubert3, Axel Wehrend1, Carlos Hermosilla3 Summary A total of 41 goat serum samples from 26 flocks in Hesse, Central Germany, were analyzed for the presence of specific antibodies against the abortion-causing apicomplexan parasite Neospora (N.) caninum by immuno-enzyme assay (ELISA). In total, three serum samples were seropositive for N. caninum with two of them originating from a flock in Middle-Hesse and one sample coming from a flock in Northern Hesse. Western Blotting confirmed two of three ELISA-positive samples proving a low overall prevalence of 2/41 (0.48%) for caprine neosporosis. No clinical signs related to neosporosis were detected in any seropositive animal. -

Dual Study Programme

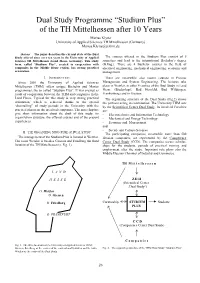

Dual Study Programme “Studium Plus” of the TH Mittelhessen after 10 Years Marius Klytta University of Applied Sciences TH Mittelhessen (Germany) [email protected] Abstract — The paper describes the current state of the Dual Study offered since over ten years in the University of Applied The courses offered in the Studium Plus consist of 6 Sciences TH Mittelhessen (Land Hesse, Germany). This study semesters and lead to the international Bachelor´s degree form, called “Studium Plus”, created in cooperation with (B.Eng.). There are 4 Bachelor courses in the field of companies in the Middle Hesse region, has strong practical electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, economy and orientation. management. I. INTRODUCTION There are meanwhile also master courses in Process Since 2001 the University of Applied Sciences Management and System Engineering. The lectures take Mittelhessen (THM) offers unique Bachelor and Master place in Wetzlar, in other 4 centres of the Dual Study in Land programmes, the so called “Studium Plus ”. It was created as Hesse (Biedenkopf, Bad Hersfeld, Bad Wildungen, result of cooperation between the THM and companies in the Frankenberg) and in Giessen. Land Hesse. Typical for this study is very strong practical The organizing structure of the Dual Study (Fig.2) shows orientation, which is achieved thanks to the special the partners acting in combination. The University THM acts “dovetailing” of study periods in the University with the by the Scientifical Center Dual Study . Its involved Faculties practical phases in the involved companies. The next chapters are: give short information about the draft of this study, its - Electrotechnics and Information Technology organization structure, the offered courses and of the present - Mechanical and Energy Technology experiences. -

Cultural Wealth. Culture Map of Hesse … a Cultural Discovery Tour

www.hessen-tourism.com Preserving our cultural wealth. CULTURE MAP OF HESSE … a cultural discovery tour EUROPEAN UNION Investing in Your Future European Regional Development Fund RZ_Titel_Kulturkarte_engl.indd 1 03.12.2009 12:07:12 Uhr Dear Guest, ... take our suggestions for your cultural adventure through the state of Hesse. Experience the variety and contrast of the enchanting state of Hesse. Hesse´s cultural offer is also distinguished by contrast and variety. 350 castles, over 300 museums, impressive abbeys, attractive parks and gar- dens, picturesque half-timbered towns and fi ve UNESCO-world heritage sites – discover Hesse’s rich past and present. The vibrant theater scene from the Opera House that has already recei- ved multiple awards to modern theater to experimental free theater is compelling. Artists and institutions in music, literature, dance, fi lm and the new media, fi ne arts as well as high-quality exhibitions and festivals also invite you to come to Hesse- the range of subjects is rich and enti- cing, nurtures the mind and senses. This cultural map can provide you with a little cross section of the extensive range of cultural activities in the state of Hesse. For further information please go to the specifi ed Internet addresses. Experience culture in Hesse – We look forward to meeting you! Tip: For information on environmentally-friendly travel to Hesse go to www.bahn.de/ hessen History, Architecture, Townscape Hersfeld and Lorsch must be added to this spectrum. Numerous locations such as the State Archives in Marburg, Darmstadt and Wiesbaden provide information on the shifting political fortunes of the state. -

Output 4 Pilot Projects Report

2014-1-ES01-KA202-004679 OUTPUT 4 PILOT PROJECTS REPORT April 2016 Table of Contents ABOUT THE SIMOVET PROJECT ................................................................................. 6 APPROACH OF THE PILOT PROJECTS ......................................................................... 7 FOUNDATIONS FOR THE DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION OF A FORESIGHT MODEL IN LANBIDE-BASQUE EMPLOYMENT SERVICE ................................................................ 8 Rationale / Background ............................................................................................................. 8 Context and setting/ State of the art ........................................................................................ 9 Objectives of the pilot project................................................................................................. 10 Inspiring European approaches and practices ........................................................................ 11 Working group......................................................................................................................... 12 Methods and activities ............................................................................................................ 13 Results of the project- Outputs, Outcomes, Impact ............................................................... 18 Human, technical and financial resources .............................................................................. 19 Follow up activities ................................................................................................................. -

Twelve Good Reasons to Be a Member BENEFITS OF

Rhein-Main-Taunus BENEFITS OF MEMBERSHIP Active participation in negotiating and Ladies and Gentlemen, formulating collective bargaining agreements; Twelve Good Reasons guidance on implementation to Be a Member As the employers’ association of the biggest branch of indu- stry in Hesse, we offer our members the seal of quality of a Legal guidance on all employment matters collective bargaining agreement on a social partnership basis. and representation Political consulting and lobbying Security This indicates you are an attractive employer who regulates COST SAVINGS employment conditions and differentiated remuneration Flexibility Media relations on corporate topics and AND with the help of the professional negotiations of collective advice on recruitment marketing PERFORMANCE Competence bargaining agreements. It ensures a good working atmos- IMPROVEMENT Conflict Resolution phere, provides stability in terms of planning and contributes Ergonomic analysis of process optimisation Reliability to the success of your business. Networking and exchanging experiences Change In addition, we competently advise and support all of our Experience members in all issues related to employment conditions: as Company-oriented education, training and The Employers’ Association for attorneys on labor law, as ergonomics experts on process coaching* the Metal and Electrical Network optimisation, as lobbyists in politics, as communications advisors for success on the public opinion market and in Recruitment agencies and transfer-oriented Engineering Industries in Hesse Performance recruitment marketing, as trainers in all matters of further outplacement* education and as human resources service providers. Trust *Services provided by partners Communication Reputation Friedrich Avenarius Managing Director HESSENMETALL Rhein-Main-Taunus "Even large international companies need local networks. HESSENMETALL offers companies value- adding clusters to promote problem-solving together on a cross-company basis.” „Flexible responses to a crisis require competent partners. -

Scientists Like Timber-Framed Houses They Are Developing a New Therapy for Pulmonary Infections, Work in the US and Meet in Unter- Seibertenrod

Scientists like timber-framed houses They are developing a new therapy for pulmonary infections, work in the US and meet in Unter- Seibertenrod. The idea came from the founder of the pharmaceutical company, Dr. Thomas Hofmann. His grandparents’ house is located in our village and that’s where he and his team are meeting. By Joachim Legatis Thomas Hofmann currently lives in Doylestown located in the state of Pennsylvania, but his summer vacations are spent in his old home town. That’s when his son and daughter can play with the neighbor’s children, the same way Dr. Hofmann did when he was a child and like the generations before him. He values the calm atmosphere of the Vogelsberg region and he gets his colleagues excited about the rugged landscape of the state of Middle Hesse. Dr. Kevin Stapleton flew in two days ago from Los Angeles and he admires the diverse surroundings here. Dr. Brandon Banaschewski is impressed by the small villages here: “Everybody knows everyone”. Being from Canada originally, he loves the historic timber-framed farm houses. They all stay in the historic Hofmann farm house, built in 1733. Obstacles with Skype Dr. Hofmann scheduled a work meeting for his company Qrumpharma in Unter-Seibertenrod. During their one week stay the six medical experts discuss plans over the next few months for their new drug under development: QRM-003, an antibiotic therapy to treat a particular type of lung infection. Caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), these infections are different from the bacterium being responsible for the better known tuberculosis. -

1849, Eine in Fließgewässern Des Marburger Umlandes (Mittelhessen) Häufige Hydra- Enidae-Art (Coleoptera: Hydrophiloidea)

©Erik Mauch Verlag, Dinkelscherben, Deutschland,133 Download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Lauterbornia H. 25: 133-137, Dinkelscherben, Juni 1996 Hydraena excisa Kieswetter 1849, eine in Fließgewässern des Marburger Umlandes (Mittelhessen) häufige Hydra- enidae-Art (Coleoptera: Hydrophiloidea) [Hydraena excisa Kies w etter 1849, a Hydraenid beetle common in lotic habitats near Marburg (Middle Hesse) (Coleoptera: Hydrophiloidea)] Wolfram Sondermann und Hans-Wilhelm Bohle Mit 2 Abbildungen Schlagwörter: Hydraena, Hydraenidae, Coleoptera, Insecta, Lahn, Rhein, Hessen, Deutschland, Fundmeldung, Faunistik Hydraena excisa gilt als in Deutschland sehr seltener und "stark gefährdeter" (RL-Kat.l) Was serkäfer. Im Zuge coleopterologisch orientierter Fließgewässeruntersuchungen im Raum Mar burg/Lahn konnte die Art an 12 Probestellen nachgewiesen werden und muß im Gebiet als häufig gelten. In Germany Hydraena excisa is a waterbeetle taken for very rare and endangered. In the course of coleopterological investigations of lotic habitats near Marburg/Lahn (Germany, Middle Hesse) now the species was found in 12 sample stations and has to be concerned as a common one in the area. 1 Einleitung Während im westlichen Rheinischen Schiefergebirge zahlreiche umfassende Ma- krozoobenthon-Erfassungen in Fließgewässern vorgenommen worden sind, bei denen auch die aquatischen Coleoptera Berücksichtigung gefunden haben, muß der hessische Teil des Schiefergebirges als in dieser Hinsicht nahezu unbearbei tet gelten. Ähnliches gilt auch für die rechts der Lahn gelegenen Gebiete Mittel hessens. K arner (o. J.) beklagt die generell fragmentarische Kenntnis der Kä ferfauna der nördlichen und mittleren Landesteile. Die vorliegende Arbeit möchte das Vorkommen von Hydraena excisa im Marburger Umland beleuchten und zur Kenntnis der Verbreitung der Art in Deutschland beitragen. 2 Untersuchungsgebiet (Abb.1) und Methode Zwischen 1993 und 1995 wurde die Käferfauna zahlreicher Bäche im näheren und weiteren Marburger Umland untersucht.