Blackeye Bean Production in California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vegetables, Fruits, Whole Grains, and Beans

Vegetables, Fruits, Whole Grains, and Beans Session 2 Assessment Background Information Tips Goals Vegetables, Fruit, Assessment of Whole Grains, Current Eating Habits and Beans On an average DAY, how many servings of these Could be Needs to foods do you eat or drink? Desirable improved be improved 1. Greens and non-starchy vegetables like collard, 4+ 2-3 0-1 mustard, or turnip greens, salads made with dark- green leafy lettuces, kale, broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, carrots, okra, zucchini, squash, turnips, onions, cabbage, spinach, mushrooms, bell peppers, or tomatoes (including tomato sauce) 2. Fresh, canned (in own juice or light syrup), or 3+ 1-2 0 frozen fruit or 100% fruit juice (½ cup of juice equals a serving) 3a. Bread, rolls, wraps, or tortillas made all or mostly Never Some Most of with white flour of the time the time 3b. Bread, rolls, wraps, or tortillas made all or mostly Most Some Never with whole wheat flour of the time of the time In an average WEEK, how many servings of these foods do you eat? 4. Starchy vegetables like acorn squash, butternut 4-7 2-3 0-1 squash, beets, green peas, sweet potatoes, or yams (do not include white potatoes) 5. White potatoes, including French fries and 1 or less 2-3 4+ potato chips 6. Beans or peas like pinto beans, kidney beans, 3+ 1-2 0 black beans, lentils, butter or lima beans, or black-eyed peas Continued on next page Vegetables, Fruit, Whole Grains, and Beans 19 Vegetables, Fruit, Whole Grains, Assessment of and Beans Current Eating Habits In an average WEEK, how often or how many servings of these foods do you eat? 7a. -

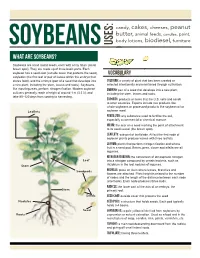

What Are Soybeans?

candy, cakes, cheeses, peanut butter, animal feeds, candles, paint, body lotions, biodiesel, furniture soybeans USES: What are soybeans? Soybeans are small round seeds, each with a tiny hilum (small brown spot). They are made up of three basic parts. Each soybean has a seed coat (outside cover that protects the seed), VOCABULARY cotyledon (the first leaf or pair of leaves within the embryo that stores food), and the embryo (part of a seed that develops into Cultivar: a variety of plant that has been created or a new plant, including the stem, leaves and roots). Soybeans, selected intentionally and maintained through cultivation. like most legumes, perform nitrogen fixation. Modern soybean Embryo: part of a seed that develops into a new plant, cultivars generally reach a height of around 1 m (3.3 ft), and including the stem, leaves and roots. take 80–120 days from sowing to harvesting. Exports: products or items that the U.S. sells and sends to other countries. Exports include raw products like whole soybeans or processed products like soybean oil or Leaflets soybean meal. Fertilizer: any substance used to fertilize the soil, especially a commercial or chemical manure. Hilum: the scar on a seed marking the point of attachment to its seed vessel (the brown spot). Leaflets: sub-part of leaf blade. All but the first node of soybean plants produce leaves with three leaflets. Legume: plants that perform nitrogen fixation and whose fruit is a seed pod. Beans, peas, clover and alfalfa are all legumes. Nitrogen Fixation: the conversion of atmospheric nitrogen Leaf into a nitrogen compound by certain bacteria, such as Stem rhizobium in the root nodules of legumes. -

Bean and Tomato Soup

Bean and Tomato Soup Schoharie County Apple Filled Squash Schoharie173 County South Grand StApple Filled Squash 173 SouthCobleskill, Grand St NY 12043 Cobleskill, NY 12043518.234.4303 Ingredients:Ingredients Instructions 518.234.4303518.296.8310 Ingredients Instructions 518.296.8310Fax: 518.234.4305 1 Tablespoon2 acorn, buttercup vegetable or oil 1. Preheat oven to 350° F. Fax: [email protected] 2 acorn,1 mediumbutternut buttercup onion, squash or chopped 1. Preheat oven to 350° F. [email protected] butternut squash 2 garlic cloves, minced 2. Cut squash in half and 2 large apples, peeled,2. Cut squashremove in half seeds. and Otsego County 2 (14½-ounce) cans white kidney beans, Otsego County123 Lake St 2 large cored,apples, chopped peeled, remove seeds. Cooperstown,123 Lake St NY 13326 cored, drained chopped and rinsed 3. Place squash halves in Cooperstown, NY 13326607.547.2536 1 (13¾-ounce)2½ Tablespoons can low brown3. sodium Place chicken squashbaking broth halvesdish cut in side down in 607.547.2536Fax: 607.547.5180 2½ Tablespoons1 cupsugar water brown baking dishabout cut 1 inchside ofdown water. in Fax: [email protected] sugar about 1 inch of water. ¼ teaspoon black pepper [email protected] 2½ Tablespoons melted 4. Bake for 20 minutes. Oneonta Outreach 2½ Tablespoons½ teaspoonbutter Italian melted seasoning, 4. Bake crushed for 20 minutes. Oneonta Outreach31 Maple St butter1 (14½-ounce) can diced tomatoes5. While squash is cooking, mix 31 Maple St Oneonta, NY 13820 5. While squash is cooking, mix Oneonta, NY 13820 1 (10-ounce)½ teaspoon package cinnamon* frozen spinach,chopped thawed apple with other 607.433.2521 ½ teaspoon cinnamon* choppedingredients. -

Directory of Us Bean Suppliers · Quality Grown in the Usa

US DRY DIRECTORY OF US BEAN SUPPLIERS · QUALITY GROWN IN THE USA BEANENGLISH SUPPLIERS DIRECTORY DRY BEANS FROM THE USA edn ll R ryn ma ber avyn eyn S an N idn inkn Cr K P ed R rk a D hernn yen ort cke dneyn zon N Bla Ki ban man at d ar Li e Re G ge r t ar G L h ig L ton Pin Liman ckn y Bla iman n ab y L dzuki B ab A B n e re G U.S. DRY BEANS www.usdrybeans.com International Year of the Pulse 2016 · www.iyop.net 01 n Pink Adzuki Large Lima Pink Garbanzo Dark Red Kidney Great Northern an Lim ge ar L Small Red Navy Black Baby Lima Blackeye Light Red Kidney in dzuk A Green Baby Lima Pinto Cranberry TABLE OF CONTENTS About the US Dry Bean Council 2 US Dry Bean Council Overseas Representatives 3 USDBC Members and Producers Organisations4 Major US Dry Bean Classes 6 Dry Bean Production Across the US 8 Companies by Bean Class 10 Alphabetical Listing Of US Dry Bean Suppliers 14 Nutritional Value 34 About the US Dry Bean Industry 36 USDBC Staff 37 02 ABOUT THE US DRY BEAN COUNCIL (USDBC) The USDBC is a trade association comprised of leaders in the bean industry with the common goal of educating US consumers about the benefits of beans. The USDBC gives a voice to the bean industry and provides information to consumers, health professionals, educators USDBC USA and the media about the good taste, nutritional value and Rebecca Bratter, Executive Director versatility of beans. -

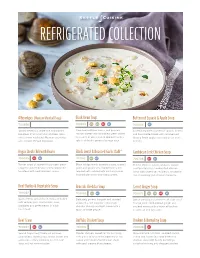

KC Refrigerated Product List 10.1.19.Indd

Created 3.11.09 One Color White REFRIGERATEDWhite: 0C 0M 0Y 0K COLLECTION Albondigas (Mexican Meatball Soup) Black Bean Soup Butternut Squash & Apple Soup 700856 700820 VN VG DF GF 700056 GF Savory meatballs, white rice and vibrant Slow-cooked black beans, red peppers, A blend of puréed butternut squash, onions tomatoes in a handcrafted chicken stock roasted sweet corn and diced green chilies and handcrafted stock with caramelized infused with traditional Mexican aromatics in a purée of vine-ripened tomatoes with a Granny Smith apples and a pinch of fresh and a touch of fresh lime juice. splash of fresh-squeezed orange juice. nutmeg. Angus Steak Chili with Beans Black Lentil & Roasted Garlic Dahl* Caribbean Jerk Chicken Soup 700095 DF GF 701762 VG GF 700708 DF GF Tender strips of seared Angus beef, green Black beluga lentils, sautéed onions, roasted Tender chicken, sweet potatoes, carrots peppers and red beans in slow-simmered garlic and ginger slow-simmered in a rich and tomatoes in a handcrafted chicken tomatoes with Southwestern spices. tomato broth, infused with warming spices, stock with white rice, red beans, traditional finished with butter and heavy cream. jerk seasoning and a hint of molasses. Beef Barley & Vegetable Soup Broccoli Cheddar Soup Carrot Ginger Soup 700023 700063 VG GF 700071 VN VG DF GF Seared strips of lean beef and pearl barley Delicately puréed broccoli and sautéed Sweet carrots puréed with fresh-squeezed with red peppers, mushrooms, peas, onions in a rich blend of extra sharp orange juice, hand-peeled ginger and tomatoes and green beans in a rich cheddar cheese and light cream with a sautéed onions with a touch of toasted beef stock. -

Crediting Legumes in the NSLP and SBP

Crediting Legumes in the National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program This guidance applies to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) meal patterns for grades K-12 and preschoolers (ages 1-4) in the National School Lunch Program (NSLP), School Breakfast Program (SBP), Seamless Summer Option (SSO) of the NSLP, and Afterschool Snack Program (ASP) of the NSLP. For information on the meal patterns and crediting foods for grades K-12, visit the Connecticut State Department of Education’s (CSDE) Meal Patterns for Grades K-12 in School Nutrition Programs and Crediting Foods in School Nutrition Programs webpages. For information on the meal patterns and crediting foods for preschoolers, visit the CSDE’s Meal Patterns for Preschoolers in School Nutrition Programs webpage. Legumes include cooked dry beans and peas, such as black beans, black-eyed peas (mature, dry), edamame (soybeans), garbanzo beans (chickpeas), kidney beans, lentils, navy beans, soybeans, split peas, and white beans. Legumes may credit as either the meat/meat alternates component or the vegetables component, but one serving cannot credit as both components in the same meal or snack. Menu planners must determine in advance how to credit legumes in a meal. A ¼-cup serving of legumes credits as 1 ounce of the meat/meat alternates component or ¼ cup of the vegetables component. Legumes may credit as either component in different meals. For example, lentils may credit as the vegetables component at one lunch, and as the meat/meat alternates component at another lunch. If the meal includes two servings of legumes, the menu planner may choose to credit one serving as the vegetables component and one serving as the meat/meat alternates component. -

Faba Bean (Vicia Faba L.) Breeding for Resistance to Anthracnose (Ascochyta Fabae Speg.) in the Czech Republic

Czech J. Genet. Plant Breed., 43, 2007 (2): 61–68 Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.) Breeding for Resistance to Anthracnose (Ascochyta fabae Speg.) in the Czech Republic Michal ONDřEJ1 and Igor HUňadY2 1Plant Protection Department and 2Grain Legumes Department, AGRITEC Ltd., Šumperk, Czech Republic Abstract: In 2003–2005 faba bean accessions were evaluated in laboratory and field inoculation tests with a mixture of differently virulent isolates for susceptibility to anthracnose caused by the fungus Ascochyta fabae Speg. All tested commercial faba bean cultivars, both colour and white flowering, were found to be susceptible or highly susceptible. The highest level of resistance was found only in declared sources of resistance: 29H, L-8 and Petra. Segregation of F2 plants derived from the cross of cultivar Merlin (susceptible, white flowering) with line Petra (resistant, colour flowering) was observed. The plants were moderately susceptible to highly suscep- tible. This finding indicates a multigenic character of resistance. Repeated selection cycles with the selection of resistant plants in F2 and F3 generations were performed. In the F4 generation, colour flowering lines with a high level of resistance, nearly at the same level as in line Petra, were obtained. In comparison with the parental cultivar Merlin an increase in the resistance of selected white flowering lines was proved. Resistance will be increased/stabilized in further repeated selection cycles. Keywords: faba bean; Vicia faba; Ascochyta fabae; anthracnose; sources of resistance; plant breeding In addition to yield losses faba bean anthracnose Jellis et al. 1984, 1991), Syria (Hanounik & Rob- causes serious problems in seed production due to ertson 1989), Canada (Kharbanda & Bernier the quality deterioration because of a high transfer 1980; Rashid et al. -

Soy Allergy Avoidance List Hidden Names for Soy Compiled by Debra A

Soy Allergy Avoidance List Hidden Names for Soy Compiled by Debra A. Indorato RD, LDN, member of KFA’s Medical Advisory Team Foods covered by the FDA labeling laws that contain soy must be labeled in plain English to declare that it “contains soy.” However, there are many foods and products that are not covered by FDA allergen labeling laws, so it is still important to know how to read a label for soy ingredients. Products exempt from plain English labeling rules: foods that are not regulated by the FDA (tinyurl.com/KFA-FALCPA), cosmetics and personal care products, prescription and over-the-counter medications or supplements, pet food, toys and crafts. contain soy The following ingredients found on a label indicate the presence of soy protein. All labels should be read carefully before consuming a product, even if it has been used safely in the past. Bean curd Soya may contain soy Edamame (soybeans in pods) Soya Flour Artificial flavoring Hydrolyzed soy protein Soybeans Asian foods (e.g. Japanese, Kinnoko flour Soybean granules Chinese, Thai, etc.) Kyodofu (freeze dried tofu) Soybean curd Hydrolyzed plant protein Miso Soybean flour Hydrolyzed vegetable protein (HVP) Natto Soy lecithin* Natural flavoring Okara (soy pulp) Soybean paste Vegetable broth Shoyu sauce Supro Vegetable gum Soy albumin Tamari Vegetable starch Soy bran Tempeh Soy concentrate Teriyaki sauce should be safe Soy oil (except cold pressed, expeller Soy fiber Textured soy flour (TSF) pressed or extruded soybean oil) Soy flour Textured soy protein (TSP) Soy formula Textured vegetable protein (TVP) Vegetable oil derived from soy Soy grits Tofu These soy derivatives should be safe Soy milk Yakidofu for most soy-allergic individuals. -

Common Bean (Phaseolus Vulgaris L.) Intercropping Response to Population Density of Component Crop in Wolaita Zone Southern Ethiopia

Journal of Natural Sciences Research www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3186 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0921 (Online) Vol.6, No.15, 2016 Maize (Zea mays L.) -Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) Intercropping Response to Population Density of Component Crop in Wolaita Zone Southern Ethiopia Abera Habte * Mesfin Kassa Adera Sisay Department of Plant Science, College of Agriculture, Wolaita Sodo University Abstract Intercropping is the common types of multiple cropping which is taken as one of the best options to increase crop productivity in area with low land holding capacity. For better effectiveness of this cropping system, optimum density of the component crops should be determined. A field experiment was conducted to evaluate the growth and yield performance of maize intercropped with different population density of common bean in Wolaita Zone, Southern Ethiopia in 2013/2014. Four ranges of population density (44444 maize ha -1 + 93750 bean ha -1, 44444 maize ha -1 + 62500 bean ha -1, 44444maize ha -1 + 0 bean ha -1 and 0 maize ha -1 + 125000 bean ha -1) were arranged in a randomized complete block design with three replications. There was no significant difference between sole cropped and intercropped maize on crop phenology, days to physiological maturity, growth parameters, yield and yield components. Sole cropped common bean had significantly higher leaf area and leaf area index than intercropped bean. Population density had significant effect on yield of common bean. The analysis of partial land equivalent ratio of the component crops showed that intercropping pattern had significant (P<0.05) effect on the partial land equivalent ratio of the bean component and but not for maize component . -

Bean Inspection Handbook (Pdf)

United States Department of Agriculture Bean Marketing and Regulatory Programs Agricultural Inspection Marketing Service Federal Grain Inspection Service Handbook Washington, D.C. July 2021 United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Marketing Service Federal Grain Inspection Service July 2021 Program Handbook Bean Inspection Handbook Foreword The Bean Inspection Handbook sets forth the policies and procedures for sampling, inspecting, and certifying dry beans in accordance with the regulations under the Agricultural Marketing Act (AMA) of 1946, as amended. These regulations establish the basic guidelines for inspecting beans and authorize the issuance of such additional guidelines as may be necessary for the interpretation and application of the United States Standards for Beans. The information contained in this handbook is applicable to official bean inspection services performed by the Federal Grain Inspection Service (FGIS), a program under the Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS), an agency or department of the Federal Government which has an interagency agreement, a State Agency or other entity which has an agreement with FGIS to conduct commodity inspection services under the AMA. Persons interested in obtaining official services may call or write any FGIS field office or cooperator. Trade names are used solely to provide specific information. The mention of trade names does not constitute a guarantee or warranty of the product by the U.S. Department of Agriculture or an endorsement by the Department over other products -

Effects of Nitrogen Fetilizer Applications in a Bean – Maize Based Intercropping Systems and Locations on Seed Quality of Common Bean in Western Kenya

International Research Journal of Agricultural Science and Soil Science (ISSN: 2251-0044) Vol. 2(11) pp. 481-492, November 2012 Available online http://www.interesjournals.org/IRJAS Copyright ©2012 International Research Journals Full Length Research Paper Effects of nitrogen fetilizer applications in a bean – maize based intercropping systems and locations on seed quality of common bean in Western Kenya 1Ogutu M.O., 2 Muasya R. and 3 Ouma G. 1Kenya Agricultural Research Institute, P.O. Box 1490, Kisumu, Kenya 2Moi University, Department of Seed Crop and Horticultural Sciences, P.O. Box 1125, Eldoret, Kenya 3School of Agriculture, Food Security and Biodiversity, Bondo University College, P.O Box 210-40601, Bondo, Kenya Abstract Common bean ( Phaseolus vulgaris L.) is an important crop in western Kenya. It is usually intercropped with maize ( Zea mays ). Combined effects of N fertilizer at two levels i.e. without N fertilizer and 50 Kg N per ha and cropping systems comprising research practice and Farmers’ practice at two planting locations in western Kenya were studied and evaluated in an intercrop system of maize and beans in the year 2006. The objectives of the study were to determine the effects of cropping systems and N fertilizer levels at different locations on the seed quality parameters of beans. Two field experiments were conducted at two Kenya Agricultural Research Institute (K.A.R.I) centers at Kibos and Kisii. The cultivars used were KK8 and H 614 for beans and maize respectively. The experiments comprised two cropping systems and two N fertilizer levels in a Completely Randomized Block design Replicated four times. -

Farm to Fork Sciences at North Dakota State University, Dr

Dr. Hall is an Associate Professor of Food Farm to Fork Sciences at North Dakota State University, Dr. Clifford Hall Fargo, North Dakota, and a Member of the [email protected] Bean Institute Editorial Board. The Cycle On the Farm Processing of the Bean The Fork Production “Farm to fork” is a model that encompasses the flow of food from the time the seed is planted until the finished product reaches the consumer’s plate. Understanding that what happens on the farm can influence the product consumed allows for the Storage production of higher quality Your Table and safer food. Processing The Cycle On the Farm Processing of the Bean The Fork Beans belong to the family of plants called legumes. A legume is a plant that produces seeds in a pod (fruit) and may have the ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen. The physi- cal shape of the seed helps distinguish beans from peas and lentils. Usually, beans are kidney-shaped or oval, peas are round and lentils are flat disks. Most dry beans grown in this country belong to the species Phaseolus vulgaris, or common bean. The term “dry beans” includes varieties of beans other than green beans, string beans and soybeans. Dry beans are available uncooked in sealed bags or pre-cooked in cans. The type or variety of bean grown is dependent on how the bean will be consumed. The beans below represent a hand full of the beans grown worldwide. Light Red Kidney Beans Pinto Beans Black Beans Navy Beans Small Red Beans The Cycle On the Farm Processing of the Bean The Fork Agronomics Bean Production: Planting Agronomics is the science and economics of crop production and land management.