Evaluating the Impact of Transit-Oriented Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doug Allen-Dallas

The DART Perspective Doug Allen Executive Vice President Program Development Dallas Area Rapid Transit Why DART? • Growing Mobility Problems • “World Class” Image • Vision 9 Fixed Guideway 9 Multi-modal 9 Regional Mobility History • DART was created to implement a vision 9 Fixed Guideway 9 Multi-modal • We had some problems along the way 9 Local economy 9 Public input 9 Political support 9 Credibility 9 Failure of Bond Referendum History • 1983 – DART established • 1988 – Bond referendum failure • 1989 – New Directions System Plan campaign • 1992 – Rail construction begins • 1996 – Opening of LRT Starter System • 2000 – Long term debt package passed • 2001-02 – Opening of extensions • 2006 – $700 Million FFGA The Mission To build and operate a safe, efficient and effective transportation system that, within the DART Service Area, provides mobility, improves the quality of life, and stimulates economic development. FY 2006 Ridership by Mode 36.1 Million 18.6 Million 18% 36% 44% 2% 2.4 Million 44.3 Million System Overview THE DART SYSTEM BUS • Provides area-wide coverage 9 700 square miles 9 Over 100 routes • Flexible 9 Local 9 Express 9 Crosstown 9 Feeders 9 Paratransit 9 Innovative services • Carries 44.3 million riders/year (FY ’06) System Overview THE DART SYSTEM Light Rail • Provides high capacity, quality transit within busiest corridors 9 20 mile Starter System 9 Additional 25 miles in 2002-3 9 Another 48 miles in planning & design • Benefits include 9 Service Reliability 9 Consistent time savings 9 Attracts new users 9 Stimulates -

ROWLETT STATION Our Speakers Bureau

inmotion the official newsletter of A PUBLICATION OF DALLAS AREA RAPID TRANSIT DALLAS AREA RAPID TRANSIT P.O. BOX 660163 DALLAS, TX 75266-0163 Nevin Grinnell Address Service Requested Vice President Chief Marketing Officer Morgan Lyons Media Relations Director Elena Rohweder Manager, Communications Lyle Miller Senior Manager, Creative Services Denise Johnson Manager, Customer Information / Production Customer Information (routes & schedules) 214.979.1111 Connect with DART DART Administrative Offices 214.749.3278 Karen Ptacek Donn Coburn Communications Representatives Thomas Santana Ron Gray Designers Joe Swift Photography Photographer To subscribe or to update or cancel your subscription to Inmotion, contact Tracy Cantu. 214.749.2543 DART: Live and Online Get updates about DART’s latest developments through DOWNTOWN ROWLETT STATION our Speakers Bureau. Invite a DART representative to talk to your organization about our family of transit services. 214.749.2524 Transit Education offers A special thanks to our partners for their generous support safety education programs for schoolchildren and special presentations and tours for seniors. 214.749.2582 Visit DART.org for the online Trip Planner, route schedules, maps, construction updates and more. BLUE LINE LinKS TO Rowlett McDonald’s ROWLETT McDonald’s 5220 N. MacArthur Irving 132-011-712TS DART Current and Future Services to 2014 A-Train to Denton (operated by DCTA) NW PLANO PARK & RIDE PLANO PARKER ROAD JACK HATCHELL TRANSIT CTR. DOWNTOWN PLANO Presiden t G e sh Turnpike orge Bu BUSH TURNPIKE NORTH CARROLLTON/FRANKFORD Dallas North Tollway GALATYN PARK TRINITY MILLS RICHARDSON T RANSIT ADDISON ARAPAHO CENTER DOWNTOWN CARROLLTON ADDISON TRANSIT CTR. CARROLLTON IS A SPRING VALLEY FARMERS BRANCH DOWNTOWN FARMERS BRANCH GARLAND GARLAND AMILY LBJ/CENTRAL DOWNTOWN F DFW ROWLETT FOREST LANE FOREST/JUPITER ROYAL LANE LBJ/SKILLMAN DFW BELT LINE ROWLETT WALNUT LAKE HIGHLANDS WALNUT HILL/DENTON HILL IRVING CONVENTION CENTER Lake Ray PARK LANE Hubbard NORTH LAKE LAS COLINAS S. -

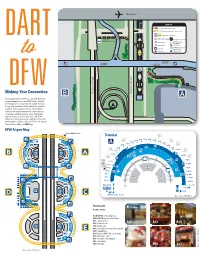

Making Your Connection

DART Rail System Map DOWNTOWN ROWLETT DFW AIRPORT STATION Open 2014 Irving Convention Center Belt Line Making Your Connection During peak times (4:30-7 a.m. and 2:15-5:30 p.m. weekday departures from DFW Airport Station), the Orange Line travels from the station through Irving, into downtown Dallas and to the northern terminus of the system at Parker Road Station in Plano. Off-peak, it follows the same path but terminates at LBJ/Central Station. Select late- night Orange Line trains will travel from DFW Exploring Airport Station to downtown; from there they will Popular Destinations go through Deep Ellum and end at Fair Park Station. Check out schedules at DART.org. DART DFW Airport Map Convention Center District. One of the largest in the nation, the Kay Bailey Hutchison (Dallas) Convention Center hosts major national and international conventions, meetings, antique and Exit to DART Station Terminal auto shows, and other events. The Omni Dallas Hotel is connected to it via sky bridge. Convention Center Station Fair Park. The largest collection of Art Deco exhibit buildings in the U.S., Fair Park is a historical treasure that plays host to the State Fair of Texas®. Other attractions include the Heart of Dallas Bowl football game and year-round museums. Fair Park Station Dallas Arts District. The Dallas Arts District is the largest arts district in the nation, spanning 68 acres and comprising Entry numerous venues of cultural as well as architectural from distinction. Pearl/Arts District Station DART Omni Dallas Hotel Station NorthPark Center. Shoppers from all over the world are drawn to NorthPark’s one-of-a-kind collection of luxury and fashion-forward retailers. -

History of Mass Transit

A NEW WAY TO CONNECT TO TRAVEL Ryan Quast Figure 1.1 A NEW WAY TO CONNECT TO TRAVEL A Design Thesis Submitted to the Department of Architecture and Landscape Architecture of North Dakota State University By Ryan Quast In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Architecture Primary Thesis Advisor Thesis Committee Chair May 2015 Fargo, North Dakota List of Tables and Figures Table of Contents Figure 1.1 Train entering COR station 1 Cover Page................................................................................................1 Taken by author Signature Page....................................................................................... ...3 Figure 1.2 Northstar commuter train 13 Table of Contents......................................................................................4 www.northstartrain.org Tables and Figures....................................................................................5 Thesis Proposal.....................................................................................10 Figure 2.1 Render of The COR 15 Thesis Abstract............................................................................11 coratramsey.com/node/23 Narrative of the Theoretical Aspect of the Thesis..................12 Figure 2.2 Development plan for COR 15 Project Typology.........................................................................13 coratramsey.com/sites/default/files/COR-Development-Plan-6.0.pdf Typological Research (Case Studies)...................................................14 -

Concept of Operations

Concept of Operations Dallas Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) Demonstration Project www.its.dot.gov/index.htm Final Report — December 2010 FHWA-JPO-11-070 1.1.1.1.1.1 1.1.1.1.1.1 Produced by FHWA Office of Operations Support Contract DTFH61-06-D-00004 ITS Joint Program Office Research and Innovative Technology Administration U.S. Department of Transportation Notice This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient’s Catalog No. FHWA-JPO-11-070 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date June 2010 Concept of Operations – Dallas Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) Demonstration Project 6. Performing Organization Code 8. Performing Organization Report No. 7. Author(s) 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) 9. Performing Organization Name And Address 11. Contract or Grant No. 12. Sponsoring Agency Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered U.S. Department of Transportation Research and Innovative Technology Administration (RITA) 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE 14. Sponsoring Agency Code Washington, DC 20590 ITS JPO 15. Supplementary Notes 16. Abstract This concept of operations (Con Ops) for the US-75 Integrated Corridor Management (ICM) Program has been developed as part of the US Department of Transportation Integrated Corridor Management Initiative, which is an innovative research initiative that is based on the idea that independent, individual, network-based transportation management systems—and their cross-network linkages—can be operated in a more coordinated and integrated manner, thereby increasing overall corridor throughput and enhancing the mobility of the corridor users. -

View a PDF of This Publication in a New Window

DALLAS AREA RAPID TRANSIT Progress Report FY 2016 BUILT TODAY. FOR TOMORROW. 132-005-117 Cover Pgs Progress Report FY2016.indd 1 2/21/17 2:36 PM DART CURRENT AND FUTURE SERVICES A-train to Denton (operated by DCTA) NW PLANO PARK & RIDE PLANO PARKER ROAD JACK HATCHELL DOWNTOWN PLANO TRANSIT CTR. SHILOH ROAD Presiden t G e sh Turnpike orge Bu CITYLINE/BUSH NORTH CARROLLTON/FRANKFORD Dallas North Tollway GALATYN PARK TRINITY MILLS ADDISON RICHARDSON ARAPAHO CENTER DOWNTOWN CARROLLTON ADDISON CARROLLTON TRANSIT CTR. SPRING VALLEY FARMERS BRANCH DOWNTOWN FARMERS BRANCH GARLAND GARLAND LBJ/CENTRAL DFW DOWNTOWN ROWLETT AIRPORT FOREST LANE FOREST/JUPITER Terminal A ROYAL LANE LBJ/SKILLMAN DFW BELT LINE ROWLETT WALNUT LAKE HIGHLANDS WALNUT HILL/DENTON HILL IRVING CONVENTION CENTER Lake Ray PARK LANE Hubbard NORTH LAKE LAS COLINAS S. GARLAND COLLEGE URBAN CENTER TRANSIT CTR. UNIVERSITY WHITE ROCK BACHMAN LOVERS UNIVERSITY OF DALLAS PARK LANE LAKE RAY LOVE HIGHLAND HUBBARD FIELD White TRANSIT CTR. BURBANK PARK MOCKINGBIRD Rock INWOOD/LOVE FIELD Lake IRVING SOUTHWESTERN MEDICAL DISTRICT/ PARKLAND DALLAS To Fort Worth CENTREPORT/ WEST IRVING DOWNTOWN IRVING/ MEDICAL/ MARKET CENTER DFW AIRPORT HERITAGE CROSSING MARKET CENTER CITYPLACE/UPTOWN DEEP ELLUM PEARL/ARTS DISTRICT VICTORY ST. PAUL BAYLOR UNIVERSITY MEDICAL CENTER AKARD WEST END FAIR PARK UNION STATION MLK, JR. Tr r in it y Rive CONVENTION CENTER LAWNVIEW CEDARS HATCHER COCKRELL HILL 8TH & CORINTH DALLAS ZOO LAKE JUNE TRE to Fort Worth TYLER/VERNON MORRELL HAMPTON ILLINOIS WESTMORELAND BUCKNER BELL RICHLAND HILLS KIEST VA MEDICAL CENTER RED BIRD LEDBETTER FORT WORTH ITC TRANSIT CTR. T&P STATION FORT WORTH CAMP WISDOM UNT DALLAS Downtown Dallas Rail System Legend GLENN VICTORY HEIGHTS Currently Operating DEEP GLENN HEIGHTS PARK & RIDE DART Rail Red Line ELLUM WEST DART Rail Blue Line TRANSFER PEARL/ARTS DISTRICT DART Rail Green Line ST. -

Highland Park Addison Garland Richardson

LAKE LEWISVILLE CUSTER SH 121 COMMUNICATIONS EADQ H U A R T EXCHANGE PKWY E PLANO LEGACY 211 R EXCHANGE PKWY S D 208 R GOLINK FRITO LAY LEGACY DR FAR NORTH PLANO SHOPS AT 452 GOLINK 452 LEGACY SPRING CREEK SPRING TENNYSON LEGACY DR LAKE LEWISVILLE 347 P 183 451 CUSTER NORTH CENTRAL PLANO/ 211 208 NORTHWEST PLANO CHASE OAKS PARK AND RIDE OHIO SH 121 PRESTON RD GOLINK COMMUNICATIONS 183, 208, 211, 347, 451, EADQ H U 452, GoLink A SPRING CREEK PKWY R 211 T EXCHANGE PKWY 211 E PLANO LEGACY 452 211 R EXCHANGE PKWY S SPRING CREEK PKWY D SH 121 R GOLINK 208 LAKESIDE US-75 N. CENTRAL EXPWY. COLLIN COUNTY FRITO LAY LEGACY DR MARKET FAR NORTH PLANO COMMUNITY 350 COLLEGE SHOPS AT 452 GOLINK JUPITER RD LEGACY 350 452 211 AVE K SPRING CREEK SPRING 451 TENNYSON LEGACY DR TEXAS HEALTH PRESBYTERIAN 347 P 183 451 HOSPITAL PLANO PARKER RD 452 COMMUNICATIONS NORTH CENTRAL347 PLANO/ PARKER RD 211 208 PARKER RD PARKER ROAD STATION CHASE OAKS 211, 350, 410, 452, GoLink NORTHWEST PLANO PRESTON RD. PARK AND RIDE OHIO 183 PRESTON RD GOLINK 410 183, 208, 211, 347, 451, 452, GoLink 350 211 SPRING CREEK PKWY CUSTER RD 211 RD COIT 452 SHOPS AT PARK BLVD PARK BLVD CREEK INDEPENDENCE WILLOWBEND ALMA 410 SH 121 SPRING CREEK PKWY LAKESIDE ARBOR 531 347 PARK BLVD 350 US-75 N. CENTRAL EXPWY. COLLIN COUNTY PARK BLVD MARKET CHEYENNE 870 COMMUNITY HEBRON 350 COLLEGE 451 18TH BAYLOR MEDICAL CTR. JUPITER RD DOWNTOWN PLANO STATION 870 AT CARROLLTON 350 211 MEDICAL CENTER PLANO 870 FLEX 208 OF PLANO 15TH AVE K 15TH TEXAS HEALTH 451 OHIO 14TH IN PRESBYTERIAN T PARKWOOD E R 350 13TH 870 HOSPITAL PLANO N PLANO PKWY A 208 210 PARKER RD 452 TIO COLLIN CREEK MALL FM 544 COMMUNICATIONS N JACK HATCHELL TRANSIT CENTER AL P 347 PARKER RD KWY 841PARKER RD 208, 210, 350, 451, 452, 841 347PARKER ROAD STATION 350 FLEX 211, 350, 410, 452, GoLink 208 BAYLOR REGIONAL 870 PRESTON RD. -

Take DART and TRE to Area Winter Wonderlands

Media Relations Contact: Morgan Lyons Mark A. Ball November 24, 2008 Holiday events just a train ride away Take DART and TRE to area winter wonderlands Looking to save money to feed your family of reindeer while enjoying the area's winter events? You can if you park your sleigh and ride Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) Rail or the Trinity Railway Express (TRE). Plan your trip by using the online DART Trip Planner at www.dart.org or call DART Customer Information at 214-979-1111. TRE information is at www.trinityrailwayexpress.org. Parades Nov. 28 The Parade of Lights kicks off the holiday season at 6 p.m. in Sundance Square with more than 100 brightly illuminated floats, bands, horse-drawn carriages, antique cars and characters decked out in their holiday best. The annual tree lighting follows, and Santa is on hand every weekend through Dec. 21 at his Nutcracker Village on Main Street. Information: 817-255- 5700, www.sundancesquare.com or www.fortworthparadeoflights.org. Ride the Trinity Railway Express (TRE) to ITC Station, then the T's bus route 1 or 15. (Note: Last eastbound TRE train to Dallas Union Station departs ITC Station at 10:36 p.m. Monday through Friday. Last eastbound TRE train to Dallas Union Station departs ITC Station at 10:36 p.m. Saturdays. No TRE service on Sundays.) Dec. 6 The Neiman Marcus Adolphus Children's Parade is fun for kids of all ages with colorful floats, giant balloons, bands, clowns, equestrian units and a visit by Santa. The parade begins at 10 a.m. -

System Map 551 829 HOPKINS R 500 DFW KIRBY 500 LEWISVILLE 987

LAKE LEWISVILLE 346 348 EXCHANGE PKWY 348 LEGACY DR PARKWOOD SH 121 SHOPS AT 452 348 452 LEGACY 346346 LEGACY DR TENNYSON 347 P 183 451 208 NORTH PLANO NORTHWEST PLANO DART ON-CALL ZONE PARK AND RIDE 183, 208, 346, 347, PRESTON RD 348, 451, 452 SPRING CREEK PKWY 452 SPRING CREEK PKWY 829 LAKESIDE US-75 N. CENTRAL EXPWY. COLLIN COUNTY MARKET COMMUNITY 350 COLLEGE JUPITER RD 350 TEXAS HEALTH 451 PLANO RD PRESBYTERIAN HOSPITAL PLANO PARKER RD 452 R RD COMMUNICATIONS 347 PARKER RD PARKER ROAD STATION PARKE 350, 410, 452 183 PRESTON RD. DART ON-CALL, TI Shuttle, Texoma Express 410 CUSTER RD SHOPS AT RD COIT PARK BLVD INDEPENDENCE PARK BLVD CREEK WILLOWBEND 410 ALMA ARBOR 531 347 PARK BLVD PARK BLVD CHEYENNE 870 451 BAYLOR MEDICAL CTR. 18TH 870 AT CARROLLTON HEBRON PLANO DOWNTOWN PLANO STATION MEDICAL CENTER 870 FLEX 208 OF PLANO 15TH 15TH OHIO 14TH IN T PARKWOOD E 350 R 13TH 870 N A PLANO PKWY TI 210 COLLIN CREEK MALL ON JACK HATCHELL TRANSIT CENTER FM 544 AL P KWY 841 210, 350, 451, 452, 841 FLEX SH-121 347 210 BAYLOR REGIONAL 870 843 AVE K AVE 843 841 MEDICAL CTR. ROSEMEADE PKWY 534 841 PLANO PKWY PLANO PKWY HEBRON to Denton (operated by DCTA) 531 347 841 MARSH LUNA 350 841 410 WAL-MART 883 Fri/Sun 841 ROUND GROVE NPIKE NORTH STAR RD TIMBERGREEN H TUR NORTH CARROLLTON/FRANKFORD STATION P S BUSH TURNPIKE STATION 333 U 883 UTD Shuttle, 841-843 FLEX PEAR RIDGE PEAR B IH-35E STEMMONS FRWY. -

TOD in Dallas: Successes & the Future

TOD in Dallas: Successes & the Future Cheri Bush, PMP Senior Planner Economic Development & Planning Dallas Area Rapid Transit September 2005 TRANSIT-ORIENTED HOUSING • DEMAND DOUBLE IN THE NEXT 20 YEARS. • 71% OF OLDER HOUSEHOLDS WANT TO BE WITHIN WALKING DISTANCE OF TRANSIT. Source: “Hidden In Plain Sight Capturing the Demand for Housing Near Transit” Reconnecting America’s Center for Transit Oriented Development (2004) BY 2025, The Dallas Area • WILL ADD 260,000+ TOD UNITS • MORE THAN A 350% INCREASE. • WILL RANK SECOND ONLY TO L.A. 61 Hours A Year Stuck in Traffic $1.3 Billion in Transit- Oriented Development RAILRAIL --SERVEDSERVED PROPERTIESPROPERTIES :: Residential: 39% greater increase Office: 53% greater increase Mockingbird Station Mockingbird Station Hotel Palomar-Mockingbird Station East Plano-Before Rail Downtown Plano Station Area Eastside Village 15 th Street Village Development "It's an amenity that is very attractive to many people … DART adds a whole new dimension of convenience to a lot of people." 15 th Street Developer Richard Howe Galatyn Park Station Area West Village Downtown Dallas Urban Market-Downtown Dallas CityVillage at Southwestern Medical District South Side On Lamar South Side On Lamar Victory Station Area Park Lane Place Planned Farmers Branch Station Planned Carrollton Square Station Carrollton or Farmers Branch conceptual drawing Planned Irving Station Area City of Dallas Resolution recognizes DART’s role in: • Increasing tax base • Improving quality of life • Spurring TOD A JOINT DEVELOPMENT BETWEEN… • CITIES • TRANSIT AGENCIES • DEVELOPERS & INVESTORS For Further Information: Cheri Bush,PMP Senior Planner •214.749.2568 •[email protected] www.dart.org/economicdevelopment.asp. -

Gold Line Corridor Economic Development and Community Services Strategy

Final Report Gold Line Corridor Economic Development and Community Services Strategy Prepared for: Gold Line Corridor Working Group and Denver Regional Council of Governments Prepared by: Economic & Planning Systems, Inc. with ArLand Land Use Economics and Ordonez and Vogelsang, LLC January 16, 2015 EPS #143020 Table of Contents 1. GOLD LINE CORRIDOR ASSESSMENT ........................................................................... 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Vision and Goals ....................................................................................................... 1 Gold Line Corridor Strengths and Weaknesses .............................................................. 2 Corridor Market Potentials .......................................................................................... 3 2. CORRIDOR-WIDE STRATEGIES .................................................................................. 6 Complete Transit Corridor .......................................................................................... 6 Corridor-wide Collaboration ........................................................................................ 8 3. STATION AREA ACTION PLANS ................................................................................ 12 41st and Fox ........................................................................................................... 12 Pecos Junction ....................................................................................................... -

RED Light Rail Time Schedule & Line Route

RED light rail time schedule & line map Dart Light Rail - Red Line View In Website Mode The RED light rail line (Dart Light Rail - Red Line) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Northbound: 12:20 AM - 11:51 PM (2) Southbound: 12:04 AM - 11:32 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest RED light rail station near you and ƒnd out when is the next RED light rail arriving. Direction: Northbound RED light rail Time Schedule 26 stops Northbound Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:20 AM - 11:51 PM Monday 12:20 AM - 12:46 AM Westmoreland Station Tuesday Not Operational Hampton Station 1636 S Hollywood Ave, Dallas Wednesday 12:20 AM - 11:51 PM Tyler Vernon Station Thursday 12:20 AM - 11:51 PM 900 Lebanon Ave, Dallas Friday 12:20 AM - 11:51 PM Zoo Station Saturday 12:20 AM - 11:51 PM 702 S Marsalis Ave, Dallas 8th & Corinth Station 1803 E 8th St, Dallas RED light rail Info Santa Fe Junction Direction: Northbound 1115 Parker St, Dallas Stops: 26 Trip Duration: 54 min Cedars Station Line Summary: Westmoreland Station, Hampton 555 2nd Ave, Dallas Station, Tyler Vernon Station, Zoo Station, 8th & Corinth Station, Santa Fe Junction, Cedars Station, Convention Center Station Convention Center Station, Ebj Union Station, West End Station, Akard Station, St Paul Station, Ebj Union Station Pearl/Arts District Station, Cityplace/Uptown 411 S Houston St, Dallas Station, Smu/Mockingbird Station, Lovers Lane Station, Park Lane Station, Walnut Hill Station, West End Station Forest Ln Station, LBJ / Central Station, Spring