Since the Introduction of Extracorporeal Hemodialysis For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WO 2012/148799 Al 1 November 2012 (01.11.2012) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2012/148799 Al 1 November 2012 (01.11.2012) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every A61K 9/107 (2006.01) A61K 9/00 (2006.01) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, A 61 47/10 (2006.0V) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, (21) International Application Number: DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, PCT/US2012/034361 HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, (22) International Filing Date: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, 20 April 2012 (20.04.2012) MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, (25) Filing Language: English SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, (26) Publication Language: English TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (30) Priority Data: (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 61/480,259 28 April 201 1 (28.04.201 1) US kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, (71) Applicant (for all designated States except US): BOARD UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, OF REGENTS, THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SYS¬ TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, TEM [US/US]; 201 West 7th St., Austin, TX 78701 (US). -

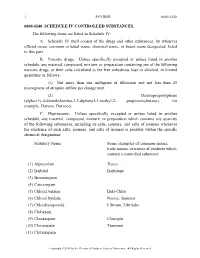

124.210 Schedule IV — Substances Included. 1

1 CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES, §124.210 124.210 Schedule IV — substances included. 1. Schedule IV shall consist of the drugs and other substances, by whatever official name, common or usual name, chemical name, or brand name designated, listed in this section. 2. Narcotic drugs. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation containing any of the following narcotic drugs, or their salts calculated as the free anhydrous base or alkaloid, in limited quantities as set forth below: a. Not more than one milligram of difenoxin and not less than twenty-five micrograms of atropine sulfate per dosage unit. b. Dextropropoxyphene (alpha-(+)-4-dimethylamino-1,2-diphenyl-3-methyl-2- propionoxybutane). c. 2-[(dimethylamino)methyl]-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol, its salts, optical and geometric isomers and salts of these isomers (including tramadol). 3. Depressants. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation which contains any quantity of the following substances, including its salts, isomers, and salts of isomers whenever the existence of such salts, isomers, and salts of isomers is possible within the specific chemical designation: a. Alprazolam. b. Barbital. c. Bromazepam. d. Camazepam. e. Carisoprodol. f. Chloral betaine. g. Chloral hydrate. h. Chlordiazepoxide. i. Clobazam. j. Clonazepam. k. Clorazepate. l. Clotiazepam. m. Cloxazolam. n. Delorazepam. o. Diazepam. p. Dichloralphenazone. q. Estazolam. r. Ethchlorvynol. s. Ethinamate. t. Ethyl Loflazepate. u. Fludiazepam. v. Flunitrazepam. w. Flurazepam. x. Halazepam. y. Haloxazolam. z. Ketazolam. aa. Loprazolam. ab. Lorazepam. ac. Lormetazepam. ad. Mebutamate. ae. Medazepam. af. Meprobamate. ag. Methohexital. ah. Methylphenobarbital (mephobarbital). -

Drugs of Abuseon September Archived 13-10048 No

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE DRUG ENFORCEMENT ADMINISTRATION WWW.DEA.GOV 9, 2014 on September archived 13-10048 No. v. Stewart, in U.S. cited Drugs of2011 Abuse EDITION A DEA RESOURCE GUIDE V. Narcotics WHAT ARE NARCOTICS? Also known as “opioids,” the term "narcotic" comes from the Greek word for “stupor” and originally referred to a variety of substances that dulled the senses and relieved pain. Though some people still refer to all drugs as “narcot- ics,” today “narcotic” refers to opium, opium derivatives, and their semi-synthetic substitutes. A more current term for these drugs, with less uncertainty regarding its meaning, is “opioid.” Examples include the illicit drug heroin and pharmaceutical drugs like OxyContin®, Vicodin®, codeine, morphine, methadone and fentanyl. WHAT IS THEIR ORIGIN? The poppy papaver somniferum is the source for all natural opioids, whereas synthetic opioids are made entirely in a lab and include meperidine, fentanyl, and methadone. Semi-synthetic opioids are synthesized from naturally occurring opium products, such as morphine and codeine, and include heroin, oxycodone, hydrocodone, and hydromorphone. Teens can obtain narcotics from friends, family members, medicine cabinets, pharmacies, nursing 2014 homes, hospitals, hospices, doctors, and the Internet. 9, on September archived 13-10048 No. v. Stewart, in U.S. cited What are common street names? Street names for various narcotics/opioids include: ➔ Hillbilly Heroin, Lean or Purple Drank, OC, Ox, Oxy, Oxycotton, Sippin Syrup What are their forms? Narcotics/opioids come in various forms including: ➔ T ablets, capsules, skin patches, powder, chunks in varying colors (from white to shades of brown and black), liquid form for oral use and injection, syrups, suppositories, lollipops How are they abused? ➔ Narcotics/opioids can be swallowed, smoked, sniffed, or injected. -

A. Schedule IV Shall Consist Of

1 REVISOR 6800.4240 6800.4240 SCHEDULE IV CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES. The following items are listed in Schedule IV: A. Schedule IV shall consist of the drugs and other substances, by whatever official name, common or usual name, chemical name, or brand name designated, listed in this part. B. Narcotic drugs. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation containing any of the following narcotic drugs, or their salts calculated as the free anhydrous base or alkaloid, in limited quantities as follows: (1) Not more than one milligram of difenoxin and not less than 25 micrograms of atropine sulfate per dosage unit. (2) Dextropropoxyphene (alpha-(+)-4-dimethylamino-1,2-diphenyl-3-methyl-2- propionoxybutane), for example, Darvon, Darvocet. C. Depressants. Unless specifically excepted or unless listed in another schedule, any material, compound, mixture, or preparation which contains any quantity of the following substances, including its salts, isomers, and salts of isomers whenever the existence of such salts, isomers, and salts of isomers is possible within the specific chemical designation: Statutory Name Some examples of common names, trade names, or names of products which contain a controlled substance (1) Alprazolam Xanax (2) Barbital Barbitone (3) Bromazepam (4) Camazepam (5) Chloral betaine Beta-Chlor (6) Chloral hydrate Noctec, Somnos (7) Chlordiazepoxide Librium, Libritabs (8) Clobazam (9) Clonazepam Clonopin (10) Clorazepate Tranxene (11) Clotiazepam Copyright ©2013 -

152.02 Schedules of Controlled Substances; Administration of Chapter

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2010 152.02 152.02 MS 1967 [Repealed, 1969 c 933 s 22] 152.02 SCHEDULES OF CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES; ADMINISTRATION OF CHAPTER. Subdivision 1. Five schedules. There are established five schedules of controlled substances, to be known as Schedules I, II, III, IV, and V. Such schedules shall initially consist of the substances listed in this section by whatever official name, common or usual name, chemical name, or trade name designated. Subd. 2. Schedule I. The following items are listed in Schedule I: (1) Any of the following substances, including their isomers, esters, ethers, salts, and salts of isomers, esters, and ethers, unless specifically excepted, whenever the existence of such isomers, esters, ethers and salts is possible within the specific chemical designation: Acetylmethadol; Allylprodine; Alphacetylmethadol; Alphameprodine; Alphamethadol; Benzethidine; Betacetylmethadol; Betameprodine; Betamethadol; Betaprodine; Clonitazene; Dextromoramide; Dextrorphan; Diampromide; Diethyliambutene; Dimenoxadol; Dimepheptanol; Dimethyliambutene; Dioxaphetyl butyrate; Dipipanone; Ethylmethylthiambutene; Etonitazene; Etoxeridine; Furethidine; Hydroxypethidine; Ketobemidone; Levomoramide; Levophenacylmorphan; Morpheridine; Noracymethadol; Norlevorphanol; Normethadone; Norpipanone; Phenadoxone; Phenampromide; Phenomorphan; Phenoperidine; Piritramide; Proheptazine; Properidine; Racemoramide; Trimeperidine. (2) Any of the following opium derivatives, their salts, isomers and salts of isomers, unless specifically excepted, whenever -

Drugs and Medical Devices Group

TEXAS DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AUSTIN, TEXAS INTER-OFFICE MEMORANDUM TO: Charles E. Bell, M.D. Executive Deputy Commissioner THRU: Susan K. Steeg, General Counsel Office of General Counsel THRU: Debra C. Stabeno, M.P.H. Deputy Commissioner for Programs FROM: Richard B. Bays Associate Commissioner for Consumer Health Protection DATE: October 11, 2001 SUBJECT: Order Amending Controlled Substance Schedules • Pursuant to Section 481.034(g), as amended by the 75th legislature, of the Texas Controlled Substances, Act Chapter 481, Health and Safety Code, your signature as Executive Deputy Commissioner and the seal of the Department are required on the attached order. Please note date of signing to be entered in the last paragraph of the order. • If you concur, please return the original document bearing your signature and seal to the Drugs and Medical Devices Division where it will be retained as an official record. Attachments The Acting Administrator of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has issued a final rule listing the substance dichloralphenazone, including its salts, isomers, and salts of isomers in Schedule IV of the Federal Controlled Substances Act (CSA). Dichloralphenazone is a sedative typically used in combination with isometheptene mucate and acetaminophen in formulating prescription pharmaceuticals for the relief of tension and vascular headache. Since dichloralphenazone is a compound containing chloral hydrate, it is likewise a Schedule IV depressant. This action was based on the following: (1) dichloralphenazone is a compound containing two molecules of chloral hydrate and one molecule of phenazone; (2) chloral hydrate is a Schedule IV depressant; and, (3) since dichloralphenazone has not been recognized as a compound containing chloral hydrate and confusion has existed with regard to its control status, the DEA issued a proposed rule in the Federal Register on December 11, 2000 to expressly list dichloralphenazone as a Schedule IV depressant. -

Jack Deruiter, Principles of Drug Action 2, Fall 2003 1

Jack DeRuiter, Principles of Drug Action 2, Fall 2003 BARBITURATE ANALOGUES AND OTHER SEDATIVE-HYPNOTICS I. Primidone (Mysoline) O CH2CH3 O CH2CH3 R H N N H ON O N O H H H Phenobarbital Primidone ("2-deoxyphenobarbital") Structure, Chemistry and Actions: The 2-deoxy analogue of phenobarbital. Primidone is similar to phenobarbital in its chemical properties, except that it is not acidic (not an imide!). It is metabolized by oxidation to phenobarbital and phenylethylmalonamide (PEMA), both of which have anticonvulsant activity (tonic/clonic and partial seizures) and may express their actions by a mechanism similar to the barbiturates (GABA actions). Thus primidone could be considered to be a prodrug: O CH2CH3 H N O CH2CH3 O N O H O CH2CH3 CYP H N H Phenobarbital H CYP N N O H HO H N O O CH CH H 2 3 Primidone H (2-deoxyphenobarbital) H2N Oxidation Intermediate H2N O PEMA Absorption/Distribution: Primidone is readily absorbed from the GI tract yielding peak serum concentrations occur in 3 hours. Peak serum concentrations of PEMA occur after 7 to 8 hours. Phenobarbital appears in plasma after several days of continuous therapy. Protein binding of primidone and PEMA is negligible; phenobarbital is about 50% protein bound. Monitoring of primidone therapy should include plasma level determinations of primidone and phenobarbital. Metabolism/Execretion: PEMA is the major metabolite and is less active than primidone. Phenobarbital formation ranges from 15% to 25%. The plasma half-life of primidone is 5-15 hours. PEMA and phenobarbital have longer half-lives (10-18 hours and 53-140 hours, respectively) and accumulate with chronic use. -

Drug/Substance Trade Name(S)

A B C D E F G H I J K 1 Drug/Substance Trade Name(s) Drug Class Existing Penalty Class Special Notation T1:Doping/Endangerment Level T2: Mismanagement Level Comments Methylenedioxypyrovalerone is a stimulant of the cathinone class which acts as a 3,4-methylenedioxypyprovaleroneMDPV, “bath salts” norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor. It was first developed in the 1960s by a team at 1 A Yes A A 2 Boehringer Ingelheim. No 3 Alfentanil Alfenta Narcotic used to control pain and keep patients asleep during surgery. 1 A Yes A No A Aminoxafen, Aminorex is a weight loss stimulant drug. It was withdrawn from the market after it was found Aminorex Aminoxaphen, Apiquel, to cause pulmonary hypertension. 1 A Yes A A 4 McN-742, Menocil No Amphetamine is a potent central nervous system stimulant that is used in the treatment of Amphetamine Speed, Upper 1 A Yes A A 5 attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, narcolepsy, and obesity. No Anileridine is a synthetic analgesic drug and is a member of the piperidine class of analgesic Anileridine Leritine 1 A Yes A A 6 agents developed by Merck & Co. in the 1950s. No Dopamine promoter used to treat loss of muscle movement control caused by Parkinson's Apomorphine Apokyn, Ixense 1 A Yes A A 7 disease. No Recreational drug with euphoriant and stimulant properties. The effects produced by BZP are comparable to those produced by amphetamine. It is often claimed that BZP was originally Benzylpiperazine BZP 1 A Yes A A synthesized as a potential antihelminthic (anti-parasitic) agent for use in farm animals. -

Hypnotic Drugs RUSSELL R

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.46.535.314 on 1 May 1970. Downloaded from Pcstgraduate Medical Journal (May 1970) 46, 314-317. CURRENT SURVEY Hypnotic drugs RUSSELL R. MILLER* DIRK V. DEYOUNG Pharm. D. M.D. Director, Drug Communications Study, Assistant Medical Director, University of Chicago Continental Assurance Company, Chicago JAMES PAXINOS B.S (Pharm.) Assistant Director for Clinical Services, Department ofPharmacy, University of Chicago Hospitals and Clinics THIS review will treat the more commonly prescribed Human pharmacology hypnotic agents and their sleep-inducing properties. In the past, hypnotics have been divided into Hypnotic agents that are seldom used (paraldehyde), barbiturates and non-barbiturates. This classification, drugs that are not singularly soporific but may be based on chemical structure, has little contemporary used either alone or as adjuncts in inducing sleep [e.g. clinical significance since compounds in each group meprobamate (Equanil, Miltown), chlordiazepoxide have essentially the same qualitative pharmacologic (Librium) and diazepam (Valium)] and drugs that properties. Naturally, there are quantitative differ- copyright. have little soporific effect [antihistamines, bromides ences in onset and duration of action. and methylparafynol (Oblivon, Dormison) (Lasagna, 1954)] will not be discussed. Onset of action Indications Onset is generally rapid with liquid preparations Insomnia is an extremely common complaint with such as syrup of chloral hydrate (Noctec, Somnos), which are confronted. -

A Summary of California's Alcohol and Drug Abuse Laws

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. A SUMMARY OF CALIFORNIA'S ALCOHOL AND DRUG ABUSE LAWS Prepared pursuant to SB 2599 (Seymour), (Chapter 983, Statutes of 1988) Prepared by: SENATE OFFICE OF RESEARCH Elisabeth Kersten, Director June 3D, 1989 462-8 127464 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the person or organization originating It. Points of view or opinions stated In this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted bl:: California Legislature to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further reproduction outside of the NCJRS system requires permis sion of the copyright owner. A SUMMARY OF CALIFORNIA'S ALCOHOL AND DRUG ABUSE LAWS Prepared pursuant to SB 2599 (Seymour), (Chapter 983, Statutes of 1988) June 30, 1989 Prepared by: SENATE OFFICE OF RESEARCH, Ken Hurdle, Project Director, Kim Connor, Dan Englund, Dolores Sanchez, Lenore Tate Edited by: Judith A. Ryder, Thomas F. Wilspn ~;:- ~~~: ~M8ERS: ~ILLIAM A. CRAVEN to DAVIS CALIFORNIA LEGISLATURE VADIE DEDDEH TERRI DELGADILLO ~'ECIL GREEN , COMMITTEE CONSULTANT ;'ARY HART !ILL" LOCKYER STATE CAPITOL. ROOM 3074 !'E8ECCA MORGAN SACRAMENTO. CA 95814 ilCHOLAS PETRIS (916) 445-4264 to ROYCE ~ANEWATSON ~ SENATE SELECT COMMITTEE ~ ON ~ ~:, SUBSTANCE ABUSE r~, ~ t; JOHN SEYMOUR ~: !i CHAIRMAN 1 ~~ tl December 19, 1989 r1 \i ~ ~, As Chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Substance l\ Abuse, I am pleased to participate with the Senate Office of I' Research in the release of A Summary of California's Alcohol ~ and Drug Abuse Laws. -

State of Oklahoma

1 STATE OF OKLAHOMA 2 2nd Session of the 53rd Legislature (2012) 3 COMMITTEE SUBSTITUTE FOR 4 HOUSE BILL NO. 2808 By: Roberts (Sean) 5 6 7 COMMITTEE SUBSTITUTE 8 An Act relating to public health and safety; amending 63 O.S. 2011, Section 2-210, which relates to 9 Schedule IV controlled substances; prohibiting the sale of certain products except by certain 10 individuals; requiring determination be made prior to dispensing certain products; providing basis of 11 determination; permitting State Board of Pharmacy to adopt certain rules, review determinations, and take 12 disciplinary action; excluding civil liability from certain determination; prohibiting certain 13 individuals from selling certain products to certain underage individuals; requiring proof of age and 14 identity prior to sale of certain products; defining term; permitting Board to adopt rules which add to 15 list of certain drugs; and providing an effective date. 16 17 18 19 BE IT ENACTED BY THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA: 20 SECTION 1. AMENDATORY 63 O.S. 2011, Section 2-210, is 21 amended to read as follows: 22 Section 2-210. A. Any material, compound, mixture, or 23 preparation which contains any quantity of the following substances 24 Req. No. 9906 Page 1 1 having a potential for abuse associated with a stimulant or 2 depressant effect on the central nervous system: 3 1. Chloral betaine; 4 2. Chloral hydrate; 5 3. Ethchlorvynol; 6 4. Ethinamate; 7 5. Meprobamate; 8 6. Paraldehyde; 9 7. Petrichloral; 10 8. Diethylpropion; 11 9. Phentermine; 12 10. Pemoline; 13 11. Chlordiazepoxide; 14 12. -

Proposed Regulation of the State Board Of

PROPOSED REGULATION OF THE STATE BOARD OF PHARMACY LCB File No. R079-15 September 16, 2015 EXPLANATION – Matter in italics is new; matter in brackets [omitted material] is material to be omitted. AUTHORITY: §1, NRS 453.146, 453.2182 and 639.070. A REGULATION relating to controlled substances; adding lorcaserin to the controlled substances listed in schedule IV in conformity with federal regulations; and providing other matters properly relating thereto. Legislative Counsel’s Digest: Existing law authorizes the State Board of Pharmacy to adopt regulations to add, delete or reschedule substances listed as controlled substances in schedules I, II, III, IV and V of the Uniform Controlled Substances Act. (NRS 453.146) Existing law also provides that if a substance is designated, rescheduled or deleted as a controlled substance pursuant to federal law, the Board is required, with certain limited exceptions, to similarly treat the substance under the Uniform Controlled Substances Act. (NRS 453.2182) The Drug Enforcement Administration of the United States Department of Justice has added lorcaserin to the list of controlled substances in schedule IV of the federal Controlled Substances Act. (78 Fed. Reg. 26,701-26,705) This regulation brings the treatment of lorcaserin into conformity with federal regulations by adding it to the list of controlled substances in schedule IV of the Uniform Controlled Substances Act. Section 1. NAC 453.540 is hereby amended to read as follows: 453.540 1. Schedule IV consists of the drugs and other substances listed in this section, by whatever official, common, usual, chemical or trade name designated. 2.