Perpetual Motion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Beatles), 80, 165, 357, 358, 389

Index of Titles Abbey Road (The Beatles), 80, 165, 357, 358, 389 “Abraham, Martin and John” (Dion), 40, 75, 115, 194, 321 Absolutely Free (The Mothers of Invention), 156, 310, 375, 388 “Absolutely Sweet Marie” (Bob Dylan), 207 “The Acid Queen” (The Who), 71 “Across the Universe” (The Beatles), 222, 309, 374 “Action” (Freddy Cannon), 69 “Adagio Per Archi e Organo” (Brian Auger and the Trinity), 72 After Bathing at Baxter’s (Jefferson Airplane), 358, 388 “After the Lights Go Down Low” (Al Hibbler), 337 “Afterglow” (The Small Faces), 357 Aftermath (The Rolling Stones), 292 “Ahab the Arab” (Ray Stevens), 25, 95, 366 “Aiko Biaye” (Ginger Baker’s Air Force), 374 “Ain’t It Funky Now” (James Brown), 212 “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” (Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell), 77, 111–112, 128 “Ain’t That a Shame” (Pat Boone), 314; (Fats Domino), 321 “Ain’t That Peculiar” (Marvin Gaye), 168 “Ain’t Too Proud to Beg” (The Temptations), 105, 124, 226, 319 “The Air That I Breathe” (The Hollies), 196 “Al Di Lá” (Emilio Pericoli), 114–115 “Alabama Song (Whisky Bar)” (The Doors), 115, 366 “Albatross” (Fleetwood Mac), 16, 377 “Albert’s Shuffle” (Mike Bloomfield / Al Kooper / Steve Stills), 62 “Alfie” (Dionne Warwick), 174, 199, 206, 279–280, 386 “Alice’s Restaurant Massacree” (Arlo Guthrie), 141, 203, 270, 327, 364, 379 “Alice’s Rock & Roll Restaurant” (Arlo Guthrie), 31, 327 “All Alone Am I” (Brenda Lee), 182 “All Along the Watchtower” (Bob Dylan), 172, 260 “The All-American Boy” (Bill Parsons), 175 “All Around the World” (Little Willie John), 139 “All Day and -

Download Our Student Guide for Over-18S

St Giles International London Highgate, 51 Shepherds Hill, Highgate, London N6 5QP Tel. +44 (0) 2083400828 E: [email protected] ST GILES GUIDE FOR STUDENTS AGED 18 LONDON IGHGATE AND OVER H Contents Part 1: St Giles London Highgate ......................................................................................................... 3 General Information ............................................................................................................................. 3 On your first day… ............................................................................................................................... 3 Timetable of Lessons ............................................................................................................................ 4 The London Highgate Team ................................................................................................................. 5 Map of the College ............................................................................................................................... 6 Courses and Tests ................................................................................................................................. 8 Self-Access ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Rules and Expectations ...................................................................................................................... 10 College Facilities ............................................................................................................................... -

AHCN2013 Leonardo Piece Ahnert Mod SEA W Fig

John Cotton Steven Cotton John Flood Thomas Whittle's wife Hugh Fox John Devenish Female prisoners in the Counter Mistress Lounford All the true professor and lovers of God's holy gospel John Hullier Cambridge congregation John Hullier's Cambridge congregation London Filles William Cooper John Denley Robert Samuel Robert Samuel's congregation at Barholt? Christian congregation (at Barholt, Suffolk?) Cutbert Simon Jen John Spenser John Harman Mrs Roberts Nicholas Hopkins Katherine Phineas Mistress Wod Amos Tyms Richard Nicholl Tyms - all Gods faithfull seruantes Ms Colfoxe congregation of Freewillers scattered through Suffolk, Norfolk, Essex and Kent Master Chester Henry Burgess a female sustainer Anon_189 godly women from William Tyms's parish of Hockley, Essex Christopher Lister William Tyms's congregation in Hockley, Essex M. William Brasburge William Tyms's friends in Hockley, Essex William Mowrant Cornelius Stevenson Master Pierpoint Walter Sheterden Thomas Simpson John Careless's co-religionist AC John Careless's co-religionists in London g- Nicholas Sheterden's mother John Careless's co-religionist EH Agnes Glascocke Stephen Gratwick Margery Cooke's husband e- Anon_234_female_E.K. Watts Thomas Whittle a- n- John Ardeley John Cavell Margaret Careless Richard Spurge m- Clement Throgmorton r- George Ambrose lo the flock in London u- Nicholas Margery Cooke's mother John Simpson Anon_289_female_E.K. Robert Drake Thomas Spurge we we r- Sister Chyllerde John Tudson n- o Alexander Thomas Harland Thyme/Thynne William Aylesbury p- m- u- John -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 2001, Tanglewood

SEMI OIAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK PRINCIPAL GUEST CONDUCTOR • i DALE CHIHULY INSTALLATIONS AND SCULPTURE / "^ik \ *t HOLSTEN GALLERIES CONTEMPORARY GLASS SCULPTURE ELM STREET, STOCKBRIDGE, MA 01262 . ( 41 3.298.3044 www. holstenga I leries * Save up to 70% off retail everyday! Allen-Edmoi. Nick Hilton C Baccarat Brooks Brothers msSPiSNEff3svS^:-A Coach ' 1 'Jv Cole-Haan v2^o im&. Crabtree & Evelyn OB^ Dansk Dockers Outlet by Designs Escada Garnet Hill Giorgio Armani .*, . >; General Store Godiva Chocolatier Hickey-Freeman/ "' ft & */ Bobby Jones '.-[ J. Crew At Historic Manch Johnston & Murphy Jones New York Levi's Outlet by Designs Manchester Lion's Share Bakery Maidenform Designer Outlets Mikasa Movado Visit us online at stervermo OshKosh B'Gosh Overland iMrt Peruvian Connection Polo/Ralph Lauren Seiko The Company Store Timberland Tumi/Kipling Versace Company Store Yves Delorme JUh** ! for Palais Royal Phone (800) 955 SHOP WS »'" A *Wtev : s-:s. 54 <M 5 "J* "^^SShfcjiy ORIGINS GAUCftV formerly TRIBAL ARTS GALLERY, NYC Ceremonial and modern sculpture for new and advanced collectors Open 7 Days 36 Main St. POB 905 413-298-0002 Stockbridge, MA 01262 Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Ray and Maria Stata Music Directorship Bernard Haitink, Principal Guest Conductor One Hundred and Twentieth Season, 2000-2001 SYMPHONY HALL CENTENNIAL SEASON Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Peter A. Brooke, Chairman Dr. Nicholas T. Zervas, President Julian Cohen, Vice-Chairman Harvey Chet Krentzman, Vice-Chairman Deborah B. Davis, Vice-Chairman Vincent M. O'Reilly, Treasurer Nina L. Doggett, Vice-Chairman Ray Stata, Vice-Chairman Harlan E. Anderson John F. Cogan, Jr. Edna S. -

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD

A Brief History of Christ Church MEDIEVAL PERIOD Christ Church was founded in 1546, and there had been a college here since 1525, but prior to the Dissolution of the monasteries, the site was occupied by a priory dedicated to the memory of St Frideswide, the patron saint of both university and city. St Frideswide, a noble Saxon lady, founded a nunnery for herself as head and for twelve more noble virgin ladies sometime towards the end of the seventh century. She was, however, pursued by Algar, prince of Leicester, for her hand in marriage. She refused his frequent approaches which became more and more desperate. Frideswide and her ladies, forewarned miraculously of yet another attempt by Algar, fled up river to hide. She stayed away some years, settling at Binsey, where she performed healing miracles. On returning to Oxford, Frideswide found that Algar was as persistent as ever, laying siege to the town in order to capture his bride. Frideswide called down blindness on Algar who eventually repented of his ways, and left Frideswide to her devotions. Frideswide died in about 737, and was canonised in 1480. Long before this, though, pilgrims came to her shrine in the priory church which was now populated by Augustinian canons. Nothing remains of Frideswide’s nunnery, and little - just a few stones - of the Saxon church but the cathedral and the buildings around the cloister are the oldest on the site. Her story is pictured in cartoon form by Burne-Jones in one of the windows in the cathedral. One of the gifts made to the priory was the meadow between Christ Church and the Thames and Cherwell rivers; Lady Montacute gave the land to maintain her chantry which lay in the Lady Chapel close to St Frideswide’s shrine. -

The Eagle 1946 (Easter)

THE EAGLE ut jVfagazine SUPPORTED BY MEMBERS OF Sf 'John's College St. Jol.l. CoIl. Lib, Gamb. VOL UME LIl, Nos. 231-232 PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS FOR SUBSCRIBERS ON L Y MCMXLVII Ct., CONTENTS A Song of the Divine Names . PAGE The next number shortly to be published will cover the 305 academic year 1946/47. Contributions for the number The College During the War . 306 following this should be sent to the Editors of The Eagle, To the College (after six war-years in Egypt) 309 c/o The College Office, St John's College. The Commemoration Sermon, 1946 310 On the Possible Biblical Origin of a Well-Known Line in The The Editors will welcome assistance in making the Chronicle as complete a record as possible of the careers of members Hunting of the Snark 313 of the College. The Paling Fence 315 The Sigh 3 1 5 Johniana . 3 16 Book Review 319 College Chronicle : The Adams Society 321 The Debaj:ing Society . 323 The Finar Society 324 The Historical Society 325 The Medical Society . 326 The Musical Society . 329 The N ashe Society . 333 The Natural Science Club 3·34 The 'P' Club 336 Yet Another Society 337 Association Football 338 The Athletic Club 341 The Chess Club . 341 The Cricket Club 342 The Hockey Club 342 L.M.B.C.. 344 Lawn Tennis Club 352 Rugby Football . 354 The Squash Club 358 College Notes . 358 Obituary: Humphry Davy Rolleston 380 Lewis Erle Shore 383 J ames William Craik 388 Kenneth 0 Thomas Wilson 39 J ames 391 John Ambrose Fleming 402 Roll of Honour 405 The Library . -

Annual Report 2016

McGill Library and Archives Annual Report 2016 Annual Report 2016 1 Table of Contents 1. Dean’s Message ------------------------------------------ 1 2. Research and Publications ------------------------------- 2 3. Teaching and Learning ----------------------------------- 3 4. Involvement in the Community --------------------------- 5 5. Human Resources: Milestones --------------------------- 10 6. Honours, Awards and Prizes ----------------------------- 10 7. Fiat Lux -------------------------------------------------- 11 8. Facilities ------------------------------------------------- 12 9. Budget --------------------------------------------------- 13 10. Fundraising ---------------------------------------------- 15 11. Academic Unit Reviews ---------------------------------- 16 Appendices A. Selected Research & Publications ----------------------- 17 B. Human Resources Report -------------------------------- 19 C. Loaned Items -------------------------------------------- 23 D. Notable Rare & Special Acquisitions --------------------- 24 E. Facts and Figures ---------------------------------------- 26 Annual Report 2016 2 Dean’s Message 2016 was a great year for the McGill Library and Archives. We are at a pivotal point in our history and much of the year was dedicated to promoting and advancing Fiat Lux, our ambitious plan to reimagine the McLennan-Redpath Complex for the 21st century. The project team (myself, Planning and Resources and Communications staff, University Advancement, McGill’s Planning Department, VP University Services, -

London National Park City Week 2018

London National Park City Week 2018 Saturday 21 July – Sunday 29 July www.london.gov.uk/national-park-city-week Share your experiences using #NationalParkCity SATURDAY JULY 21 All day events InspiralLondon DayNight Trail Relay, 12 am – 12am Theme: Arts in Parks Meet at Kings Cross Square - Spindle Sculpture by Henry Moore - Start of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail, N1C 4DE (at midnight or join us along the route) Come and experience London as a National Park City day and night at this relay walk of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail. Join a team of artists and inspirallers as they walk non-stop for 48 hours to cover the first six parts of this 36- section walk. There are designated points where you can pick up the trail, with walks from one mile to eight miles plus. Visit InspiralLondon to find out more. The Crofton Park Railway Garden Sensory-Learning Themed Garden, 10am- 5:30pm Theme: Look & learn Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, SE4 1AZ The railway garden opens its doors to showcase its plans for creating a 'sensory-learning' themed garden. Drop in at any time on the day to explore the garden, the landscaping plans, the various stalls or join one of the workshops. Free event, just turn up. Find out more on Crofton Park Railway Garden Brockley Tree Peaks Trail, 10am - 5:30pm Theme: Day walk & talk Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, London, SE4 1AZ Collect your map and discount voucher before heading off to explore the wider Brockley area along a five-mile circular walk. The route will take you through the valley of the River Ravensbourne at Ladywell Fields and to the peaks of Blythe Hill Fields, Hilly Fields, One Tree Hill for the best views across London! You’ll find loads of great places to enjoy food and drink along the way and independent shops to explore (with some offering ten per cent for visitors on the day with your voucher). -

336737 1 En Bookfrontmatter 1..24

Universitext Universitext Series editors Sheldon Axler San Francisco State University Carles Casacuberta Universitat de Barcelona Angus MacIntyre Queen Mary University of London Kenneth Ribet University of California, Berkeley Claude Sabbah École polytechnique, CNRS, Université Paris-Saclay, Palaiseau Endre Süli University of Oxford Wojbor A. Woyczyński Case Western Reserve University Universitext is a series of textbooks that presents material from a wide variety of mathematical disciplines at master’s level and beyond. The books, often well class-tested by their author, may have an informal, personal even experimental approach to their subject matter. Some of the most successful and established books in the series have evolved through several editions, always following the evolution of teaching curricula, into very polished texts. Thus as research topics trickle down into graduate-level teaching, first textbooks written for new, cutting-edge courses may make their way into Universitext. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/223 W. Frank Moore • Mark Rogers Sean Sather-Wagstaff Monomial Ideals and Their Decompositions 123 W. Frank Moore Sean Sather-Wagstaff Department of Mathematics School of Mathematical and Statistical Wake Forest University Sciences Winston-Salem, NC, USA Clemson University Clemson, SC, USA Mark Rogers Department of Mathematics Missouri State University Springfield, MO, USA ISSN 0172-5939 ISSN 2191-6675 (electronic) Universitext ISBN 978-3-319-96874-2 ISBN 978-3-319-96876-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-96876-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018948828 Mathematics Subject Classification (2010): 13-01, 05E40, 13-04, 13F20, 13F55 © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2018 This work is subject to copyright. -

Proceedings and Notes 2011

THE ART WORKERS’ GUILD PROCEEDINGS AND NOTES : NUMBER 26 : FEBRUARY 2012 MESSAGE FROM THE MASTER At this time of year, January/February, the moment comes to rake the fire in the hope of getting it going again in the morning. It is my favourite time of the year, by reason of the subtlety of colour which draws your attention to the slightest change of tone both in nature and in buildings. The sedge is with’red on the lake And no bird sings. Filigree trees, almost colourless horizons, dark accents in the foreground that are not really dark at all. It is not that this light can’t be found in Europe or elsewhere, but to uncover the beauty to be found in such insignificance you need to live in these islands. The colours reminiscent of the raw materials of craft, of vegetable dyes, semi-precious stones, various kinds of wood and a hundred different shades of brick; dead- ness without rottenness. Cold weather that is invigorating, mild weather which is somnolent and almost inert; this is a good time of year to put one’s house in order. I take my place in a very long line of people who have railed against the destruction of the countryside, but actually it hasn’t all gone (as I like to tell myself) and in fact, if it is destroyed it grows back remarkably quickly. It is the same with the arts. If at any time standards seem to slip one doesn’t have to wait long before a new avenue opens up in which those lost virtues can be expressed. -

PROGRAM NOTES Guided Tour

13/14 Season SEP-DEC Ted Kurland Associates Kurland Ted The New Gary Burton Quartet 70th Birthday Concert with Gary Burton Vibraphone Julian Lage Guitar Scott Colley Bass Antonio Sanchez Percussion PROGRAM There will be no intermission. Set list will be announced from stage. Sunday, October 6 at 7 PM Zellerbach Theatre The Annenberg Center's Jazz Series is funded in part by the Brownstein Jazz Fund and the Philadelphia Fund For Jazz Legacy & Innovation of The Philadelphia Foundation and Philadelphia Jazz Project: a project of the Painted Bride Art Center. Media support for the 13/14 Jazz Series provided by WRTI and City Paper. 10 | ABOUT THE ARTISTS Gary Burton (Vibraphone) Born in 1943 and raised in Indiana, Gary Burton taught himself to play the vibraphone. At the age of 17, Burton made his recording debut in Nashville with guitarists Hank Garland and Chet Atkins. Two years later, Burton left his studies at Berklee College of Music to join George Shearing and Stan Getz, with whom he worked from 1964 to 1966. As a member of Getz's quartet, Burton won Down Beat Magazine's “Talent Deserving of Wider Recognition” award in 1965. By the time he left Getz to form his own quartet in 1967, Burton had recorded three solo albums. Borrowing rhythms and sonorities from rock music, while maintaining jazz's emphasis on improvisation and harmonic complexity, Burton's first quartet attracted large audiences from both sides of the jazz-rock spectrum. Such albums as Duster and Lofty Fake Anagram established Burton and his band as progenitors of the jazz fusion phenomenon. -

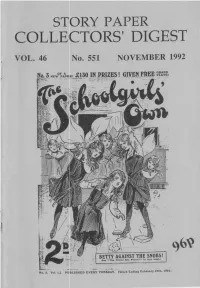

Colle1ctors' Digest

S PRY PAPER COLLE 1CTORS' DIGEST VOL. 46 No. 551 NOVEMBER 1992 BETTY AGAINST THE SNOBSI 8M u TIH Fri ... d atie ,..,,.,,d I'' II\ thi• IHllt.) - • ..a.... - No, 3, Vol . I ,) PU81. I SH£0 £VER Y TUESDAY, [Wnk End•nll f'~b,.,&ry l&th, 191 1, ONCORPORATING NORMAN SHAW) ROBIN OSBORNE, 84 BELVEDERE ROAD, LONDON SE 19 2HZ PHONE (BETWEEN 11 A.M . • 10 P.M.) 081-771 0541 Hi People, Varied selection of goodies on offer this month:- J. Many loose issues of TRIUMPH in basically very good condition (some staple rust) £3. each. 2. Round volume of TRIUMPH Jan-June 1938 £80. 3. GEM . bound volumes· all unifonn · 581. 620 (29/3 · 27.12.19) £110 621 . 646 (Jan· June 1920) £ 80 647 • 672 (July · Dec 1920) £ 80 4. 2 Volumes of MAGNET uniformly bound:- October 1938 - March 1939 £ 60 April 1939 - September 1939 £ 60 (or the pair for £100) 5. SWIFT - Vol. 7, Nos.1-53 & Vol. 5 Nos.l-52, both bound in single volumes £50 each. Many loose issues also available at £1 each - please enquire. 6. ROBIN - Vol.5, Nos. 1-52, bound in one volume £30. Many loose issues available of this title and other pre-school papers like PLA YHOUR, BIMBO, PIPPIN etc. at 50p each (substantial discounts for quantity), please enquire. 7. EAGLE - many issues of this popular paper. including some complete unbound volumes at the following rates: Vol. 1-10, £2 each, and Vol. 11 and subsequent at £1 each. Please advise requirements. 8. 2000 A.D.