Discrimination by Omission, Or We Can Call It “Exclusion from the Process,” Or It Can Be Called a ‘Lack of Voice,’ and ‘Invisibility.’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCSC Biobibliography - Rick Prelinger 9/21/19, 06�19

UCSC Biobibliography - Rick Prelinger 9/21/19, 0619 Curriculum Vitae September 21, 2019 (last update 2018-01-03) Rick Prelinger Professor Porter College [email protected] RESEARCH INTERESTS Critical archival studies; personal and institutional recordkeeping; access to the cultural and historical record; media and social change; appropriation, remix and reuse; useful cinema (advertising, educational, industrial and sponsored film); amateur and home movies; participatory documentary; digital scholarship; cinema and public history; cinema and cultural geography; urban history and film; history, sociology and culture of wireless communication; media archaeology; community archives and libraries; cultural repositories in the Anthropocene. Research and other activities described at http://www.prelinger.com. TEACHING INTERESTS Useful cinema and ephemeral media; amateur and home movies; found footage; history of television; personal media; critical archival studies; access to cultural record EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Jul 1 2017 - Present Professor, Department of Film & Digital Media, UC Santa Cruz Jul 1999 - Present Director of Moving Images, Consultant, Advisor, and other positions (intermittent between 1999-2016). Currently pro bono consultant and member of the Board of Directors, Internet Archive, San Francisco, California. 1984 - Present Founder and President, Prelinger Associates, Inc. (succeeded by Prelinger Archives LLC) Fall 2013 - Spring 2017 Acting Associate Professor, Department of Film & Digital Media, UC Santa Cruz Oct 3 2005 - Dec 2006 Head, Open Content Alliance, a group of nonprofit organizations, university libraries, archives, publishers, corporations and foundations dedicated to digitizing books and other cultural resources in an open-access environment. OCA was headquartered at Internet Archive and supported by Yahoo, Microsoft Corporation and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Fall 1998 - Winter 1999 Instructor, MFA Design Program, School of Visual Arts, New York, N.Y. -

Native Peoples of North America

Native Peoples of North America Dr. Susan Stebbins SUNY Potsdam Native Peoples of North America Dr. Susan Stebbins 2013 Open SUNY Textbooks 2013 Susan Stebbins This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Published by Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library (IITG PI) State University of New York at Geneseo, Geneseo, NY 14454 Cover design by William Jones About this Textbook Native Peoples of North America is intended to be an introductory text about the Native peoples of North America (primarily the United States and Canada) presented from an anthropological perspective. As such, the text is organized around anthropological concepts such as language, kinship, marriage and family life, political and economic organization, food getting, spiritual and religious practices, and the arts. Prehistoric, historic and contemporary information is presented. Each chapter begins with an example from the oral tradition that reflects the theme of the chapter. The text includes suggested readings, videos and classroom activities. About the Author Susan Stebbins, D.A., Professor of Anthropology and Director of Global Studies, SUNY Potsdam Dr. Susan Stebbins (Doctor of Arts in Humanities from the University at Albany) has been a member of the SUNY Potsdam Anthropology department since 1992. At Potsdam she has taught Cultural Anthropology, Introduction to Anthropology, Theory of Anthropology, Religion, Magic and Witchcraft, and many classes focusing on Native Americans, including The Native Americans, Indian Images and Women in Native America. Her research has been both historical (Traditional Roles of Iroquois Women) and contemporary, including research about a political protest at the bridge connecting New York, the Akwesasne Mohawk reservation and Ontario, Canada, and Native American Education, particularly that concerning the Native peoples of New York. -

BAD RIVER BAND of LAKE SUPERIOR TRIBE of CHIPPEWA INDIANS CHIEF BLACKBIRD CENTER Box 39 ● Odanah, Wisconsin 54861

BAD RIVER BAND OF LAKE SUPERIOR TRIBE OF CHIPPEWA INDIANS CHIEF BLACKBIRD CENTER Box 39 ● Odanah, Wisconsin 54861 July 11, 2020 Ben Callan, WDNR Division of External Services PO Box 7921 Madison, WI 53708-7921 [email protected] RE: Comments Concerning the Enbridge Energy, LLC Line 5 Relocation around the Bad River Reservation regarding the WDNR Wetland and Water Crossing Permits and the EIS Scoping Dear Mr. Callan, As a sovereign nation with regulatory authority over downstream waters within the Bad River Watershed, on-Reservation air quality, and an interest in the use and enjoyment of the sacred waters of Anishinaabeg-Gichigami, or Lake Superior, pursuant to treaties we signed with the United States, we submit our comments related to the potential Line 5 Reroute around the Bad River Reservation proposed by Enbridge Energy, LLC (henceforth, “company” or “applicant”). The Bad River Band of Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians (henceforth, “Tribe”) is a federally-recognized Indian Tribe centered on the northern shores of Wisconsin and Madeline Island, where the Bad River Indian Reservation is located, but the Tribe also retains interest in ceded lands in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota. These lands were ceded to the United States government in the Treaties of 18371, 18422, and 18543. The proposed Line 5 Reroute falls within these ceded lands where the Tribe has retained usufructuary rights to use treaty resources. In addition, it threatens the water quality of the Tribe’s waters downstream, over which the Tribe has regulatory authority as a sovereign nation and as delegated by the federal government under the Clean Water Act. -

Born of Clay Ceramics from the National Museum of The

bornclay of ceramics from the National Museum of the American Indian NMAI EDITIONS NATIONAL MUSEUM OF THE AMERICAN INDIAN SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION WASHINGTON AND NEW YORk In partnership with Native peoples and first edition cover: Maya tripod bowl depicting a their allies, the National Museum of 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 bird, a.d. 1–650. campeche, Mexico. the American Indian fosters a richer Modeled and painted (pre- and shared human experience through a library of congress cataloging-in- postfiring) ceramic, 3.75 by 13.75 in. more informed understanding of Publication data 24/7762. Photo by ernest amoroso. Native peoples. Born of clay : ceramics from the National Museum of the american late Mississippian globular bottle, head of Publications, NMai: indian / by ramiro Matos ... [et a.d. 1450–1600. rose Place, cross terence Winch al.].— 1st ed. county, arkansas. Modeled and editors: holly stewart p. cm. incised ceramic, 8.5 by 8.75 in. and amy Pickworth 17/4224. Photo by Walter larrimore. designers: ISBN:1-933565-01-2 steve Bell and Nancy Bratton eBook ISBN:978-1-933565-26-2 title Page: tile masks, ca. 2002. Made by Nora Naranjo-Morse (santa clara, Photography © 2005 National Museum “Published in conjunction with the b. 1953). santa clara Pueblo, New of the american indian, smithsonian exhibition Born of Clay: Ceramics from Mexico. Modeled and painted ceram institution. the National Museum of the American - text © 2005 NMai, smithsonian Indian, on view at the National ic, largest: 7.75 by 4 in. 26/5270. institution. all rights reserved under Museum of the american indian’s Photo by Walter larrimore. -

African Journal of Criminology and Justice Studies: AJCJS, Vol.4, No.1

African Journal of Criminology and Justice Studies: AJCJS, Vol.8, Special Issue 1: Indigenous Perspectives and Counter Colonial Criminology November 2014 ISSN 1554-3897 Indigenous Feminists Are Too Sexy for Your Heteropatriarchal Settler Colonialism Andrea Smith University of California Abstract Within the creation myths of the United States, narratives portray Native peoples as hypersexualized and sexually desiring white men and women. Native men in captivity narratives are portrayed as wanting to rape white women and Native women such as Pocahontas are constituted as desiring the love and sexual attention of white men at the expense of her Native community. In either of these accounts of settler colonialism, Native men and women’s sexualities are read as out of control and unable to conform to white heteropatriarchy. Many Native peoples respond to these images by desexualizing our communities and conforming to heteronormativity in an attempt to avoid the violence of settler-colonialism. I interrogate these images and provide sex-positive alternatives for Native nation building as an important means of decolonizing Native America. Keywords Indigenous feminists, heteropatriarchy, settler colonialism, anti-violence. Introduction . Sexy futures for Native feminisms. Chris Finley (2012) Chris Finley signals a new direction emerging out of the Indigenous anti-violence movement in Canada and the United States. This strand of the anti-violence organizing and scholarship builds on the work of previous indigenous anti-violence advocates who have centered gender violence as central to anti-colonial struggle. However, as the issue of violence against Indigenous women gains increasing state recognition, this strand has focused on building indigenous autonomous responses to violence that are not state-centered. -

Nazca Culture Azca Flourished in the Ica and Rio Grande De Nazca River Valleys of Southern Peru, Nin an Extremely Arid Coastal Zone Just West of the Andes

Nazca Culture azca flourished in the Ica and Rio Grande de Nazca river valleys of southern Peru, Nin an extremely arid coastal zone just west of the Andes. Nazca chronology is generally broken into four main periods: 1) Proto-Nazca or Nazca 1, from the decline of Paracas culture in the second century BCE until about 0 CE; 2) Early Nazca (or Nazca 2–4), from ca. 0 CE to 450 CE; 3) A transitional Nazca 5 from 450–550 CE; and 4) Late Nazca (phases 6–7), from about 550–750 CE. Nazca 5 witnesses the beginning of environmental changes thought to be associated with the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO), cycles of warm and cold water that interrupt the cold, low-salinity Humboldt Current that flows along the Peruvian coast. A 2009 study in Latin American Antiquity suggests that the Nazca may have contributed to this environmental collapse by clearing the land of huarango trees (Prosopis pallida, a kind of mesquite) which played a crucial role in preventing erosion. While best known for their pottery and the Nazca lines (geoglyphs created in the surrounding desert), perhaps their greatest achievement was the construction of extensive puquios, or underground aqueducts channeling water from aquifers, similar in purpose and construction to the qanats of the ancient Middle East. Through the use of puquios the ancient Nazca made parts of the desert bloom; many Nazca puquios remain in use today. Some scholars long doubted that the puquios were made by the Nazca, but in 1995 chronometric dates using accelerator mass spectrometry confirmed dates in the sixth century CE and earlier. -

Beyond Blood Quantum: the Legal and Political Implications of Expanding Tribal Enrollment

American Indian Law Journal Volume 3 Issue 1 Article 8 12-15-2014 Beyond Blood Quantum: The Legal and Political Implications of Expanding Tribal Enrollment Tommy Miller Harvard Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/ailj Part of the Cultural Heritage Law Commons, and the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Tommy (2014) "Beyond Blood Quantum: The Legal and Political Implications of Expanding Tribal Enrollment," American Indian Law Journal: Vol. 3 : Iss. 1 , Article 8. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/ailj/vol3/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications and Programs at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in American Indian Law Journal by an authorized editor of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Beyond Blood Quantum: The Legal and Political Implications of Expanding Tribal Enrollment Cover Page Footnote Tommy Miller is a 2015 J.D. Candidate at Harvard Law School and a member of the Colville Confederated Tribes. He would like to thank his family for their constant support and inspiration, Professor Joe Singer for his guidance, and the staff of the American Indian Law Journal for their hard work. This article is available in American Indian Law Journal: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/ailj/vol3/iss1/8 AMERICAN INDIAN LAW JOURNAL Volume III, Issue I – Fall 2014 BEYOND BLOOD QUANTUM THE LEGAL AND POLITICAL IMPLICATIONS OF EXPANDING TRIBAL ENROLLMENT ∗ Tommy Miller INTRODUCTION Tribal nations take many different approaches to citizenship. -

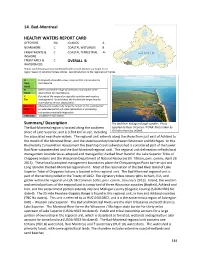

14-Bad-Montreal BCA Regional Unit Background Chapter

14. Bad-Montreal HEALTHY WATERS REPORT CARD OFFSHORE NA ISLANDS A NEARSHORE C COASTAL WETLANDS B EMBAYMENTS & C COASTAL TERRESTRIAL A+ INSHORE TRIBUTARIES & C OVERALL B WATERSHEDS Report card denotes general condition/health of each biodiversity target in the region based on condition/stress indices. See introduction to the regional summaries. A Ecologically desirable status; requires little intervention for Very maintenance Good B Within acceptable range of variation; may require some Good intervention for maintenance. C Outside of the range of acceptable variation and requires Fair management. If unchecked, the biodiversity target may be vulnerable to serious degradation. D Allowing the biodiversity target to remain in this condition for Poor an extended period will make restoration or preventing extirpation practically impossible. Unknown Insufficient information. Summary/ Description The Bad River Kakagon Slough complex. Photo The Bad-Montreal region is located along the southern supplied by Ryan O’Connor, WDNR. Photo taken by shore of Lake Superior, and is 3,764 km2 in size, including Christina Isenring, WDNR. the associated nearshore waters. The regional unit extends along the shore from just east of Ashland to the mouth of the Montreal River, and the state boundary line between Wisconsin and Michigan. In this Biodiversity Conservation Assessment the Beartrap Creek subwatershed is considered part of the Lower Bad River subwatershed and the Bad-Montreal regional unit. This regional unit delineation reflects local management boundaries as adopted and managed by the Bad River Band of the Lake Superior Tribe of Chippewa Indians and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (N. Tillison, pers. comm., April 26 2013). -

Origins There Is Not Enough Evidence to Assert What Conditions Gave Rise to the First Cities

City A city is a relatively large and permanent human settlement.[1][2] Although there is no agreement on how a city is distinguished from a town within general English language meanings, many cities have a particular administrative, legal, or historical status based on local law. Cities generally have complex systems for sanitation, utilities, land usage, housing, and transportation. The concentration of development greatly facilitates interaction between people and businesses, benefiting both parties in the process, but it also presents challenges to managing urban growth.[3] A big city or metropolis usually has associated suburbs and exurbs. Such cities are usually associated with metropolitan areas and urban areas, creating numerous business commuters traveling to urban centers for employment. Once a city expands far enough to reach another city, this region can be deemed aconurbation or megalopolis. Origins There is not enough evidence to assert what conditions gave rise to the first cities. However, some theorists have speculated on what they consider suitable pre- conditions, and basic mechanisms that might have been important driving forces. The conventional view holds that cities first formed after the Neolithic revolution. The Neolithic revolution brought agriculture, which made denser human populations possible, thereby supporting city development.[4] The advent of farming encouraged hunter-gatherers to abandon nomadic lifestyles and to settle near others who lived by agricultural production. The increased population-density encouraged by farming and the increased output of food per unit of land created conditions that seem more suitable for city-like activities. In his book, Cities and Economic Development, Paul Bairoch takes up this position in his argument that agricultural activity appears necessary before true cities can form. -

Sexual Violence Against the Outsiders of Society in The Round House

Sexual Violence Against the Outsiders of Society in The Round House, Bitter in the Mouth, and The Color Purple by Toni Lee December, 2020 Director of Thesis: Dr. Richard Taylor Major Department: English This thesis will examine why the outsiders to society are more susceptible to violence, particularly sexual violence. America has been led predominantly by white males, white males who have oppressed individuals who do not fit into the white male majority for years. It is my argument that when women of color are born, they are automatically labeled as outsiders due to their race and gender. An outsider is simply one who does not fit into a particular group, the group in this case being white males. While some white women experience sexual violence, their socioeconomic status and race often allows them to receive justice, especially if their perpetrator is a man of color. I will also examine other factors that lead to sexual violence, particularly rape for these outsiders, such as social class and age. This thesis analyzes three primary texts: the 2010 novel Bitter in the Mouth by Monique Truong, the 2012 novel The Round House by Louise Erdrich, and the 1982 novel The Color Purple by Alice Walker. The women in these novels, Linda, Geraldine, and Celie, respectively are sexually assaulted. It is my argument that women of color’s race/ethnicity make them more susceptible to violence, both physical and sexual, from others. These texts showcase how women are labelled as outsiders because of their races and their gender, creating a dual outsider status in the white male dominated America; thus, making them more vulnerable to sexual assault and less likely to receive justice. -

Wisconsin's Wetland Gems

100 WISCONSIN WETLAND GEMS ® Southeast Coastal Region NE-10 Peshtigo River Delta o r SC-1 Chiwaukee Prairie NE-11 Point Beach & Dunes e i SC-2 Des Plaines River NE-12 Rushes Lake MINNESOTA k e r a p Floodplain & Marshes NE-13 Shivering Sands & L u SC-3 Germantown Swamp Connected Wetlands S SC-4 Renak-Polak Woods NE-14 West Shore Green Bay SU-6 SU-9 SC-5 Root River Riverine Forest Wetlands SU-8 SU-11 SC-6 Warnimont Bluff Fens NE-15 Wolf River Bottoms SU-1 SU-12 SU-3 SU-7 Southeast Region North Central Region SU-10 SE-1 Beulah Bog NC-1 Atkins Lake & Hiles Swamp SU-5 NW-4 SU-4 SE-2 Cedarburg Bog NC-2 Bear Lake Sedge Meadow NW-2 NW-8 MICHIGAN SE-3 Cherokee Marsh NC-3 Bogus Swamp NW-1 NW-5 SU-2 SE-4 Horicon Marsh NC-4 Flambeau River State Forest NW-7 SE-5 Huiras Lake NC-11 NC-12 NC-5 Grandma Lake NC-9 SE-6 Lulu Lake NC-6 Hunting River Alders NW-10 NC-13 SE-7 Milwaukee River NC-7 Jump-Mondeaux NC-8 Floodplain Forest River Floodplain NW-6 NC-10 SE-8 Nichols Creek NC-8 Kissick Alkaline Bog NW-3 NC-5 NW-9 SE-9 Rush Lake NC-9 Rice Creek NC-4 NC-1 SE-10 Scuppernong River Area NC-10 Savage-Robago Lakes NC-2 NE-7 SE-11 Spruce Lake Bog NC-11 Spider Lake SE-12 Sugar River NC-12 Toy Lake Swamp NC-6 NC-7 Floodplain Forest NC-13 Turtle-Flambeau- NC-3 NE-6 SE-13 Waubesa Wetlands Manitowish Peatlands W-7 NE-9 WISCONSIN’S WETLAND GEMS SE-14 White River Marsh NE-2 Northwest Region NE-8 Central Region NE-10 NE-4 NW-1 Belden Swamp W-5 NE-12 WH-5 Mink River Estuary—Clint Farlinger C-1 Bass Lake Fen & Lunch NW-2 Black Lake Bog NE-13 NE-14 ® Creek Sedge Meadow NW-3 Blomberg Lake C-4 WHAT ARE WETLAND GEMS ? C-2 Bear Bluff Bog NW-4 Blueberry Swamp WH-2WH-7 C-6 NE-15 NE-1 Wetland Gems® are high quality habitats that represent the wetland riches—marshes, swamps, bogs, fens and more— C-3 Black River NW-5 Brule Glacial Spillway W-1 WH-2 that historically made up nearly a quarter of Wisconsin’s landscape. -

A Journey to the Wetlands of the Penokee Hills, Caroline Lake, and the Kakagon/Bad River Sloughs

A Journey to the Wetlands of the Penokee Hills, Caroline Lake, and the Kakagon/Bad River Sloughs Join Wisconsin Wetlands Association’s Executive Director Tracy Hames and the Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa on this 2-day journey to one of Wisconsin’s highest quality and most threatened watersheds. This top-to-bottom tour will introduce you to the wetland resources of the Bad River Watershed. We will explore headwater wetlands in the Penokee Hills at the site of a proposed iron mine, and visit the tribe’s extensive wild rice beds in the internationally-recognized Kakagon/Bad River Sloughs estuary along the shores of Lake Superior. We will discuss the role these wetlands play regulating the water throughout the watershed, the importance of these wetlands and rice beds to the Bad River People, and the potential impacts to these resources of a proposed iron mine. Choose from three tours: Tour 1 July 17-18, 2014 Tour 2 July 23-24, 2014 Tour 3 September 18-19, 2014 Tour Guides: Tracy Hames, Executive Director, Wisconsin Wetlands Association (all three tours) Mike Wiggins, Jr., Tribal Chairman, Bad River Band of Lake Superior Chippewa (first tour) Naomi Tillison, Water Program Director, Bad River Tribal Natural Resources (2nd & 3rd tour) Cinnamon fern in upper watershed wetland (photo by Tracy Hames) Itinerary (subject to adjustment as needed) We’ll be traveling to the Penokee Hills the morning of first day of each tour and visiting the upper watershed in the afternoon. That evening we’ll have dinner at the Deepwater Grille in Ashland.