Origins There Is Not Enough Evidence to Assert What Conditions Gave Rise to the First Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UCSC Biobibliography - Rick Prelinger 9/21/19, 06�19

UCSC Biobibliography - Rick Prelinger 9/21/19, 0619 Curriculum Vitae September 21, 2019 (last update 2018-01-03) Rick Prelinger Professor Porter College [email protected] RESEARCH INTERESTS Critical archival studies; personal and institutional recordkeeping; access to the cultural and historical record; media and social change; appropriation, remix and reuse; useful cinema (advertising, educational, industrial and sponsored film); amateur and home movies; participatory documentary; digital scholarship; cinema and public history; cinema and cultural geography; urban history and film; history, sociology and culture of wireless communication; media archaeology; community archives and libraries; cultural repositories in the Anthropocene. Research and other activities described at http://www.prelinger.com. TEACHING INTERESTS Useful cinema and ephemeral media; amateur and home movies; found footage; history of television; personal media; critical archival studies; access to cultural record EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Jul 1 2017 - Present Professor, Department of Film & Digital Media, UC Santa Cruz Jul 1999 - Present Director of Moving Images, Consultant, Advisor, and other positions (intermittent between 1999-2016). Currently pro bono consultant and member of the Board of Directors, Internet Archive, San Francisco, California. 1984 - Present Founder and President, Prelinger Associates, Inc. (succeeded by Prelinger Archives LLC) Fall 2013 - Spring 2017 Acting Associate Professor, Department of Film & Digital Media, UC Santa Cruz Oct 3 2005 - Dec 2006 Head, Open Content Alliance, a group of nonprofit organizations, university libraries, archives, publishers, corporations and foundations dedicated to digitizing books and other cultural resources in an open-access environment. OCA was headquartered at Internet Archive and supported by Yahoo, Microsoft Corporation and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. Fall 1998 - Winter 1999 Instructor, MFA Design Program, School of Visual Arts, New York, N.Y. -

Eulogio Rodriguez Jr. Ave, Pasig, 1604 Metro

The World's Property Search Starts Here C O N D O F O R R E N T Eulogio Rodriguez Jr. Ave, Bedrooms 1 Year Built 2017 Pasig, 1604 Metro Manila Bathrooms 1 Date Listed 11/28/2017 Pasig, Metro Manila Size 46 Sq Ft Listing ID GL-1511853657 Philippines Listed by: Property Owner Monthly Rent $700 For more information, visit: https://www.globallistings.com/3222181 Overview The Grove by Rockwell is a prestigious residential district in the center of the city. It continues to grow alongside Rockwell to provide residents a well-balanced lifestyle. Looking for a place to eat? The Retail Row offers great dining experience for your family, friends and neighbors, it features a wide variety of cafes and restaurants right before the entrance, including a convenience store, bank, and a grocery store to satisfy your needs. Looking for a place to exercise? We have a fully equipped gym and if you need guidance, our fitness instructors will assist you according to your workout to put you in peak condition. Some facilities available for an array of choices to enjoy your healthy routine such as our jogging paths, basketball courts, tennis courts and swimming pools. Rockwell is located at the center of Metro Manila, cities such as Mandaluyong, Makati and Ortigas are ease of convenience, especially going to shopping malls like Robinsons Galleria, SM Megamall, Tiendesitas, and Shangri-La and business and social districts like Eastwood City, Ortigas Center, Buendia and so on. for directions, the easiest path going to The Grove is to take the road in C5, if you're coming from the airport terminal, simply take a taxi (preferably Uber) and tell your driver to take the path all the way through at C5 until you get to The Grove. -

Ortigas Avenue St

200m Philippine Overseas Ocampo Employment Agency To Green Hills Zalameda Eton Cyberpod Corinthian Arcadia Avenue Yap Tabuena Notre Dame Fordham Sanso Wack Wack Robinsons Crowne E. Abello Golf & Country Plaza Galleria Galleria Club Manila Poveda Drive Meralco F.M. Zablan St L. Gardner Holiday Inn Complex Galleria CorinthianOrtigas Avenue St. Pedro Manila Executive Regency Lopez Poveda College AIC Rockwell Robinsons Empire Building Business E.D.S.A. Equitable Tower Sapphire Harvard Tower ADB Avenue Center Ortigas Shopping Malls Meralco GarnetAIC Road Grande ショッピングモール City & Tower Gaudix Drive Land Mega Plaza AIC Gold 4つの大型ショッピングモール Tower Ortigas Avenue Greenhills Ortigas のリース可能面積は約80万 Christian Fellowship Building Royal Palm m2であり、現在2,000以上 Asian Grand MC Home Emerald Depot Ortigas のショップが営業中。 Development Tower Wack Wack Road Berkeley ORTIGAS Bank The 中でも、SM Megamallはフ Sapphire STATION Jollibee Bloc ィリピン国内で3番目に大き Joy-Nostalg Plaza Metrowalk なショッピングモール(リース Center Building Strata Union Bank Ruby Road 2000 可能面積は約39,2万m2) Avenue ADB Plaza であるが、更にSM Opal Road Strata Garnet Road Onyx Road Patmera La Isla 100 Emerald Olive Megamall Dが開業予定。 Ansons Condominium Mansion Magnolia OrtigasF. Jr. Road Harvard Center また最近、Shangri-La Raffles Parc BSA Twin Corporate Chateau PlazaもNorth Wingを開業 Discovery Wynsum Center Towers Suntree したため、今後、多くの飲食 The Suites Corp Plaza City SM Prestige Tower Golf 店やファッションブランド等の Podium Emerald Tower Ortigas Megamall A Building Meralco Avenue St. Topaz Road Metro ショップが営業開始予定。 Priceton Bank Drive Francis The Orient Home Depot Dorm Square Square Millennium SM El Pueblo Real Sapphire Place Megamall C de Manila The Taipan Place The Stanford Doña Julia Vargas Avenue Centerpoint Doña Julia Vargas Avenue Doña Julia Vargas Avenue Parc Amberland One Metrobank Royal Antel Cornell Plaza Corporate SM SM Card Corporation Global Tindalo Jade Drive Corporate Center Megamall D Megamall B Center Molave Shaw Boulevard Starmall E.D.S.A. -

Country Report

10th Regional EST Forum in Asia, 14-16 March 2017, Vientiane, Lao PDR Intergovernmental Tenth Regional Environmentally Sustainable Transport (EST) Forum in Asia 2030 Road Map for Sustainable Transport ~Aligning with Sustainable Transport Development Goals (SDGs)~ Country Report (Draft) The Philippines ------------------------------------- This country report was prepared by the Government of The Philippines as an input for the Tenth Regional EST Forum in Asia. The views expressed herein do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations. 10th Regional EST Forum in Asia, 14-16 March 2017, Vientiane, Lao-PDR a) Philippines Country EST Report b) Department of Transportation (covering from Nepal EST c) List other Line Ministries/Agencies contributing to preparation of the Country Forum 2015 to Lao EST Report: Forum 2017) d) Reporting period: 2015-2017 With the objective of demonstrating the renewed interest and commitment of Asian countries towards realizing a promising decade (2010-2020) of sustainable actions and measures for achieving safe, secure, affordable, efficient, and people and environment-friendly transport in rapidly urbanizing Asia, the participating countries of the Fifth Regional EST Forum in Asia discussed and agreed on a goodwill and voluntary declaration - “Bangkok Declaration for 2020 – Sustainable Transport Goals for 2010-2020.” At the Seventh Regional EST Forum held in Bali in 2013, the participating countries adopted the “Bali Declaration on Vision Three Zeros- Zero Congestion, Zero Pollution and Zero Accidents towards Next Generation Transport Systems in Asia” reinforcing the implementation of Bangkok 2020 Declaration (2010-2020) with emphasis to zero tolerance towards congestion, pollution and road accidents in the transport policy, planning and development. -

Starbucks at the Grove Robinsons Galleria Ortigas Ave MRT Station

Robinsons Galleria The Medical City Ortigas Ave MRT Station Starbucks at The Grove Tiendesitas SM Megamall SM Center Pasig Trusted by over 1 million members Try Scribd FREE for 30 days to access over 125 million titles without ads or interruptions! Start Free Trial Cancel Anytime. Trusted by over 1 million members Try Scribd FREE for 30 days to access over 125 million titles without ads or interruptions! Start Free Trial Cancel Anytime. Trusted by over 1 million members Try Scribd FREE for 30 days to access over 125 million titles without ads or interruptions! Start Free Trial Cancel Anytime. *Get to Robinsons Galleria -- MRTT: Get down at Ortigas AAve, then walk towards Rob Galleria (5-10 min walk) -- Bus: Ride the bus marked “Ortigas ILALIM”, ask the conductor to bring you down near Rob Galleria (5 min walk) Mini-Stop Robinsons Galleria Trusted by over 1 million members Try Scribd FREE for 30 days to access over 125 million titles without ads or interruptions! Start Free Trial Cancel Anytime. Trusted by over 1 million members Try Scribd FREE for 30 days to access over 125 million titles without ads or interruptions! Start Free Trial Cancel Anytime. *Transport from Robinsons Galleria -- TTaxi: Ride a taxi cab from taxi terminal in front of Mini-Stop -- Jeep: Walk towards Ortigas AAve, ride a jeep (ROSARIO) from jeep terminal underer the overpass (for lack of better words), tell the driver “IPI lang po” (P8) -- Bus: Walk towards Ortigas AAve, ride a bus (TAAYTAAY/ROSARIO/CAINTA) that will pass by Ortigas Ave, tell the driver “IPI lang po” (P8) Jeep terminal under the overpass Buses tend to stop in this spot Taxi terminal in front of Mini-Stop Trusted by over 1 million members Try Scribd FREE for 30 days to access over 125 million titles without ads or interruptions! Start Free Trial Cancel Anytime. -

The Case of the Pasig City Bus Service

Assessing the Implementation Arrangements for a City Bus Transport System through a Hybrid PPP Model: The Case of the Pasig City Bus Service Annelie LONTOCa, German AVENGOZAb, Nelson DOROYc, Giel Sabrine CRUZd, Alpher DE VERAe , Paolo MANUELf , Candice RAMOS g, ClairedeLune VILLANUEVA h a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h School of Urban and Regional Planning, University of the Philippines a E-mail: [email protected] b E-mail: [email protected] c E-mail: [email protected] d E-mail: [email protected] e E-mail: [email protected] f E-mail: [email protected] g E-mail: [email protected] h E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The Ortigas Center is an important urban center in Metro Manila where its roads are often congested. Pasig City implemented a free bus service within Ortigas to address the need for public transportation. This Study assessed the implementation arrangements for a free bus service in Ortigas. The Study finds that there is a valid demand for the bus service as Ortigas is a key trip generator. However, the present free bus service is not financially viable. The Study shows that a fleet size fitted for demand will be more efficient than the current service. The Study finds that a Hybrid PPP Model for the bus service is more viable than a Pure PPP Model and the current arrangements. Both PPP Models will require the same institutional requirements such as a PPP Ordinance, the setting-up of a PPP Committee, and processes consistent with the awarding of local government contracts. Keywords: Local Public Transport Route Planning, Viability Assessment, PPP Bus Service 1. -

REGISTERED PET SHOPS (As of JANUARY 31, 2021) NO

BUREAU OF ANIMAL INDUSTRY - REGISTERED PET SHOPS (As of JANUARY 31, 2021) NO. REG NO. TRADE NAME BUSINESS ADDRESS NEW/ REGISTRATION VALIDITY REGION RENEWAL DATE 1 PTS - 0061 168 PET SHOP Gov. Alvarez Extension, Tetuan, Renewal 18-Jun-19 18-Jun-23 REGION IX Zamboanga City 2 PTS - 0135 3 BARKEETEERS PETSHOP Stall #4 Pet Village, Tiendesitas, Ugong, New 17-Dec-20 16-Dec-21 NCR Pasig City 3 PTS - 0100 ARJI’S PETSHOP 350 GSIS Street, Gitnang Bayan I, San Renewal 09-Jul-19 09-Jul-22 REGION IVA Mateo, Rizal 4 PTS – 0146 BARK ANG HUG PET SHOP Tiendesitas En Frontera Verde, Ugong, New 17-Dec-20 16-Dec-21 NCR Pasig City 5 PTS – 0147 BIG PAWS PET SHOP Tiendesitas En Frontera Verde, Ugong, New 17-Dec-20 16-Dec-21 NCR Pasig City 6 PTS - 0108 BIO RESEARCH, INC. CCB 43-B SM City North EDSA, Renewal 20-Jun-18 20-Jun-21 NCR North Avenue, Quezon City 7 PTS - 0118 BIO RESEARCH, INC. (SM #040-041A SM Megamall, Dona Vargas Renewal 12-Nov-18 12-Nov-21 NCR MEGAMALL) cor., EDSA, Mandaluyong City 8 PTS - 0126 BLESSETWIN PET SHOP GUITNANGBAYA, San Mateo , Rizal Renewal 03-Aug-20 03-Aug-23 REGION IVA 9 PTS – 0141 CANINE CREW Tiendesitas En Frontera Verde, Ugong, New 17-Dec-20 16-Dec-21 NCR PET SHOP Pasig City 10 PTS – 0142 CHATEAU PET SHOP Tiendesitas En Frontera Verde, Ugong, New 17-Dec-20 16-Dec-21 NCR Pasig City 11 PTS - 0060 CORNERSTONE ANIMAL HOSPITAL Jalandoni St., Jaro, Iloilo City Renewal 17-Oct-18 17-Oct-21 REGION VI AND VETERINARY SUPPLY 12 PTS - 0114 DAVAO PETCO CORPORATION SM Davao Ground Floor, Quimpo Renewal 26-Nov-19 25-Nov-22 REGION XI Boulevard, Ecoland, Davao City, Davao del Sur 13 PTS - 0124 DAVAO PETCO CORPORATION 2/F Abreeza Mall, JP Laurel Avenue, New 26-Nov-19 25-Nov-22 REGION XI (ABREEZA MALL) Bajada, Davao City 14 PTS - 0123 DAVAO PETCO CORPORATION SM Lanang Premier, Brgy. -

Robin Sutherland Oral History

Robin Sutherland Oral History San Francisco Conservatory of Music Library & Archives San Francisco Conservatory of Music Library & Archives 50 Oak Street San Francisco, CA 94102 Interview conducted January 29 and February 29, 2016 Tessa Updike, Interviewer San Francisco Conservatory of Music Library & Archives Oral History Project The Conservatory’s Oral History Project has the goal of seeking out and collecting memories of historical significance to the Conservatory through recorded interviews with members of the Conservatory's community, which will then be preserved, transcribed, and made available to the public. Among the narrators will be former administrators, faculty members, trustees, alumni, and family of former Conservatory luminaries. Through this diverse group, we will explore the growth and expansion of the Conservatory, including its departments, organization, finances and curriculum. We will capture personal memories before they are lost, fill in gaps in our understanding of the Conservatory's history, and will uncover how the Conservatory helped to shape San Francisco's musical culture through the past century. Robin Sutherland Interview This interview was conducted at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music on January 29 and February 29, 2016 in the Conservatory’s archives by Tessa Updike. Tessa Updike Tessa Updike is the archivist for the San Francisco Conservatory of Music. Tessa holds a B.A. in visual arts and has her Masters in Library and Information Science with a concentration in Archives Management from Simmons College in Boston. Previously she has worked for the Harvard University Botany Libraries and Archives and the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Use and Permissions This manuscript is made available for research purposes. -

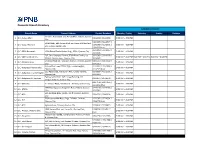

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE

Domestic Branch Directory BANKING SCHEDULE Branch Name Present Address Contact Numbers Monday - Friday Saturday Sunday Holidays cor Gen. Araneta St. and Aurora Blvd., Cubao, Quezon 1 Q.C.-Cubao Main 911-2916 / 912-1938 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 912-3070 / 912-2577 / SRMC Bldg., 901 Aurora Blvd. cor Harvard & Stanford 2 Q.C.-Cubao-Harvard 913-1068 / 912-2571 / 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Sts., Cubao, Quezon City 913-4503 (fax) 332-3014 / 332-3067 / 3 Q.C.-EDSA Roosevelt 1024 Global Trade Center Bldg., EDSA, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 332-4446 G/F, One Cyberpod Centris, EDSA Eton Centris, cor. 332-5368 / 332-6258 / 4 Q.C.-EDSA-Eton Centris 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM EDSA & Quezon Ave., Quezon City 332-6665 Elliptical Road cor. Kalayaan Avenue, Diliman, Quezon 920-3353 / 924-2660 / 5 Q.C.-Elliptical Road 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 924-2663 Aurora Blvd., near PSBA, Brgy. Loyola Heights, 421-2331 / 421-2330 / 6 Q.C.-Katipunan-Aurora Blvd. 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 421-2329 (fax) 335 Agcor Bldg., Katipunan Ave., Loyola Heights, 929-8814 / 433-2021 / 7 Q.C.-Katipunan-Loyola Heights 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Quezon City 433-2022 February 07, 2014 : G/F, Linear Building, 142 8 Q.C.-Katipunan-St. Ignatius 912-8077 / 912-8078 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM Katipunan Road, Quezon City 920-7158 / 920-7165 / 9 Q.C.-Matalino 21 Tempus Bldg., Matalino St., Diliman, Quezon City 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM 924-8919 (fax) MWSS Compound, Katipunan Road, Balara, Quezon 927-5443 / 922-3765 / 10 Q.C.-MWSS 9:00 AM – 4:00 PM City 922-3764 SRA Building, Brgy. -

Responses to the RFI

Embarcadero Historic District Request for Interest Responses to the RFI 1 Port of San Francisco Historic Piers Request for Interest Responses Table of Contents Contents #1. Ag Building / Ferry Plaza: Ferry Plaza 2.0 ................................................................................................................................................................. 4 #2. Red and White Excursions ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 31 #3. Piers 38-40: Restaurants and Recreation At South Beach ..................................................................................................................................... 34 #4. Heart of San Francisco Gondola ............................................................................................................................................................................. 47 #5. The Menlo Companies ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 50 #6. The International House of Prayer For Children ................................................................................................................................................... 53 #7 Plug and Play SF (Co-working space for startups) .................................................................................................................................................. -

A Comparative Case Study of the Transformation Fron Industry to Leisure in the Ports of San Francisco and Oakland, California

Inquiry: The University of Arkansas Undergraduate Research Journal Volume 12 Article 4 Fall 2011 Industrial Evolution: A Comparative Case Study of the Transformation fron Industry to Leisure in the Ports of San Francisco and Oakland, California. Annie Fulton University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/inquiry Part of the Environmental Design Commons, and the Urban, Community and Regional Planning Commons Recommended Citation Fulton, Annie (2011) "Industrial Evolution: A Comparative Case Study of the Transformation fron Industry to Leisure in the Ports of San Francisco and Oakland, California.," Inquiry: The University of Arkansas Undergraduate Research Journal: Vol. 12 , Article 4. Available at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/inquiry/vol12/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Inquiry: The nivU ersity of Arkansas Undergraduate Research Journal by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Fulton: Industrial Evolution: A Comparative Case Study of the Transformat ARCHITECTURE: Annie Fulton 3 INDUSTRIAL EVOLUTION: A COMPARATIVE CASE STUDY OF THE TRANSFORMATION FROM INDUSTRY TO LEISURE IN THE PORTS OF SAN FRANCISCO AND OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA By Annie Fulton Department of Architecture Faculty Mentor: Kim Sexton Department of Architecture Abstract successful conversion of an industrial port into a recreational This case study examined two waterfront sites on the San urban waterfront. Two optimal cases for study are found in the Francisco Bay – The Piers in San Francisco and Jack London San Francisco Bay Area: Piers 1 ½, 3, and 5 (constructed in 1931) Square in Oakland. -

Department of Liberal Studies School of Humanities and Liberal Studies College of Liberal and Creative Arts

Department of Liberal Studies School of Humanities and Liberal Studies College of Liberal and Creative Arts Seventh Cycle Program Review – Self Study Report December 2018 The enclosed self-study report was submitted for external review on December 13, 2017 and sent to external reviewers on March , 2018 19 1 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary 3 2. Overview of the Program 4 3. Program Indicators 6 3.1 Program Planning 6 3.2 Student Learning and Achievement 11 3.3 Curriculum 17 3.4 Faculty 23 3.5 Resources 34 4. Conclusions, Plans, and Goals 35 5. Appendices 36 5.1 Planning Worksheets 37 5.2 School of HUM & LS RTP Criteria 41 5.3 Student Evaluation of Teaching form 48 5.4 ESMR Course Scope submitted to CCTC 49 5.5 Faculty and Lecturer CVs 53 2 SECTION ONE: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Liberal Studies faculty has undertaken this self-study in the midst of a transition that has already engaged us in significant reflection on the goals, successes, and challenges of the Liberal Studies Program. In this Self-Study, we will attempt to clearly lay out where we have been, where we are now, and where we hope to be as a result of this reflection. In Spring 2015, in response to pressure from the Interim Dean of the College of Liberal and Creative Arts, the Liberal Studies program merged with the Humanities department, becoming what is now called the School of Humanities and Liberal Studies (HUMLS). The School offers three majors (Humanities, Liberal Studies, American Studies), four minors (Humanities, American Studies, California Studies and Comics Studies), and one MA program (Humanities).