Pieter Bruegel Parables of Order and Enterprise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

No Solutions for Water-Short Area

Property of the Watertown Historical Society watertownhistoricalsociety.org Timely Coverage Of News in The Fastest Growing Community in Litehfield County Vol. 40 No. 32 SUBSCRIPTION PRICE $12.00 PER, YEAR Car. Rt. P.S. PRICE 30 CENTS August 8, 1985 v Developers Raising Dust Along Main ThoroughfareNo Solutions For Site plan renderings and specifications on, paper that went to town zoning officials last fall are bearing, fruition 'this summer through, a. host of noticeable building projects underway along Main Street. All of it has left Stanley Masayda, zoning enforcement officer, with Water-Short Area; the observation that "things sure are busy!" The largest excavation project occurring these days is next to Pizza Hut, where a large sloped lot almost has been brought down to street level. The project of Anthony Cocchiola and Raymond Brennan even- tually will see a two-story office building on the site. Wells Investigated Plans were submitted to and approved by the Planning and Zoning Residents of the Grandview and Nova Scotia Hill Pair Circuit Avenues area of town, came to Monday night's Town Council meeting hoping to find sonic solu- Lodge Park Complaints tions for their ongoing dilemma of living, without adequate .water. The vice chairman, of the Town, woman Barbara HyincI,. authoriz- ed Town Manager Robert Mid- The only cone I us ion reached was Council Monday night asked the at this moment there is none, and town manager to nave a full report daugh to look into the charges made by Joseph Zu rait is, 555 Nova officials still arc trying to come up prepared for a future Council with a plan. -

Teaching the Short Story: a Guide to Using Stories from Around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 397 453 CS 215 435 AUTHOR Neumann, Bonnie H., Ed.; McDonnell, Helen M., Ed. TITLE Teaching the Short Story: A Guide to Using Stories from around the World. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-1947-6 PUB DATE 96 NOTE 311p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 19476: $15.95 members, $21.95 nonmembers). PUB 'TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) Collected Works General (020) Books (010) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC13 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Authors; Higher Education; High Schools; *Literary Criticism; Literary Devices; *Literature Appreciation; Multicultural Education; *Short Stories; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Comparative Literature; *Literature in Translation; Response to Literature ABSTRACT An innovative and practical resource for teachers looking to move beyond English and American works, this book explores 175 highly teachable short stories from nearly 50 countries, highlighting the work of recognized authors from practically every continent, authors such as Chinua Achebe, Anita Desai, Nadine Gordimer, Milan Kundera, Isak Dinesen, Octavio Paz, Jorge Amado, and Yukio Mishima. The stories in the book were selected and annotated by experienced teachers, and include information about the author, a synopsis of the story, and comparisons to frequently anthologized stories and readily available literary and artistic works. Also provided are six practical indexes, including those'that help teachers select short stories by title, country of origin, English-languag- source, comparison by themes, or comparison by literary devices. The final index, the cross-reference index, summarizes all the comparative material cited within the book,with the titles of annotated books appearing in capital letters. -

Official Directory of the European Union

ISSN 1831-6271 Regularly updated electronic version FY-WW-12-001-EN-C in 23 languages whoiswho.europa.eu EUROPEAN UNION EUROPEAN UNION Online services offered by the Publications Office eur-lex.europa.eu • EU law bookshop.europa.eu • EU publications OFFICIAL DIRECTORY ted.europa.eu • Public procurement 2012 cordis.europa.eu • Research and development EN OF THE EUROPEAN UNION BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑ∆Α • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND • ÖSTERREICH • POLSKA • PORTUGAL • ROMÂNIA • SLOVENIJA • SLOVENSKO • SUOMI/FINLAND • SVERIGE • UNITED KINGDOM • BELGIQUE/BELGIË • БЪЛГАРИЯ • ČESKÁ REPUBLIKA • DANMARK • DEUTSCHLAND • EESTI • ΕΛΛΑΔΑ • ESPAÑA • FRANCE • ÉIRE/IRELAND • ITALIA • ΚΥΠΡΟΣ/KIBRIS • LATVIJA • LIETUVA • LUXEMBOURG • MAGYARORSZÁG • MALTA • NEDERLAND -

OMUN – 2Nd Record – Tribute to the Fall

ÓMUN 2019 • NEW ALBUM « TRIBUTE TO THE FALL » WITH www.atelierhurf.net Pascal Charrier: guitar MMXVIII Julien Tamisier: keyboards, electronics Yannis Frier Yannis Philippe Lemoine: tenor saxophone > DESIGN Teun Verbruggen: drumkit, electronics GRAPHIC www.nainoprod.com ÓMUN 1 ÓMUN brings together four musicians from the European contemporary jazz and improvised music scenes: Pascal Charrier (guitar), Julien Tamisier (keyboards, electronics), Philippe Lemoine (tenor saxophone) and Teun Verbruggen (drumkit, electronics). The quartet’s sound is a combination of timbres and resonances. Every kind of approach is taken in a mixture of acoustic, electric, uncommon instrumental sounds as well as electronic and electroacoustic treatment of various sound sources. Dramatic generation of material and soundscapes disrupt bearings and invent a instantaneous poetry through processing, deconstruction and distortion. The listener navigates through a sea of reminiscences, guided by fragments of melodies like the residues of a collective memory. With this new repertory, the music places sound matter at the centre of the drama, questioning notions of permanence (emotions, bodies, ideas) and time (perpetual movement, spirals, abysses). The traditional stage/audience layout is also questioned with the creation of a circular common ground which gives both performers and audience the possibility to move around, thus changing their visual and auditive perception. This project is also pushed forward in the quintet version of the show called ÓMUN-IMAGE, in which -

Addressing the Challenge of High-Priced Prescription Drugs In

OVERVIEW Addressing the challenge of high-priced prescription drugs in the era of precision medicine: A systematic review of drug life cycles, therapeutic drug markets and regulatory frameworks Toon van der Gronde1, Carin A. Uyl-de Groot2, Toine Pieters1* a1111111111 a1111111111 1 Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences (UIPS), Utrecht University, Utrecht, the Netherlands, 2 Institute for Medical Technology Assessment, Department of Health a1111111111 Policy & Management, Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Citation: Gronde Tvd, Uyl-de Groot CA, Pieters T (2017) Addressing the challenge of high-priced Context prescription drugs in the era of precision medicine: Recent public outcry has highlighted the rising cost of prescription drugs worldwide, which in A systematic review of drug life cycles, therapeutic several disease areas outpaces other health care expenditures and results in a suboptimal drug markets and regulatory frameworks. PLoS ONE 12(8): e0182613. https://doi.org/10.1371/ global availability of essential medicines. journal.pone.0182613 Editor: Cathy Mihalopoulos, Deakin University, Method AUSTRALIA A systematic review of Pubmed, the Financial Times, the New York Times, the Wall Street Published: August 16, 2017 Journal and the Guardian was performed to identify articles related to the pricing of Copyright: © 2017 Gronde et al. This is an open medicines. access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and Findings reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Changes in drug life cycles have dramatically affected patent medicine markets, which have Data Availability Statement: All relevant data are long been considered a self-evident and self-sustainable source of income for highly profit- within the paper and its supporting information able drug companies. -

Exhibitors & Sponsors

41197 7/25/07 1:11 AM Page 8 • • • • ICPE Exhibitors and Sponsors • • • • ANNUAL MEETING SPONSORS (as of July 23, 2007) Platinum: 23rd International Conference on $12,000 LJohn Wiley & Sons Pharmacoepidemiology & Therapeutic LPfizer Risk Management Gold: $6,000 Silver: $3,000 LAmgen LAstra Zeneca Canada Sponsors LEli Lilly and Company LGenzyme LGenentech, Inc. LHealthCore LGlaxoSmithKline LPharmaNet & Li3 Drug Safety LSanofi Pasteur LKendle LMerck Research Bronze: $1,500 The International Society for Pharmacoepidemiology Laboratories LAllergan (ISPE) gratefully acknowledges the generous sup- LPharmaceutical LCephalon port of the following organizations and institutions. Research Associates LDrugLogic, Inc. Their contributions helped to enhance the scientific LProctor & Gamble LGPRD program content and increase attendance at the Pharmaceuticals LOutcome ICPE 2007. Thank you. LRoche LRisk Management LRTI Health Solutions Resources Academic Showcase/ LUnited Biosource Exhibitors Welcome Reception Sponsors Corporation LWyeth LCenter for Clinical Epidemiology & Biostatistics, University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine LCollege of Pharmacy, University of Texas LDrug Safety Research Unit, University of Portsmouth LPharmaceutical Health Services Research, University of Maryland, Baltimore LSlone Epidemiology Center, Boston University IN THIS PROGRAM LUniversity of North Carolina at Chapel Hill LDivision of Pharmacoepidemiology & Pharmacotherapy, 23rd ICPE Agenda L Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences Saturday.............................................................7 -

Startlist 2021 IRONMAN 5150 Maastricht - Limburg

Startlist 2021 IRONMAN 5150 Maastricht - Limburg Last update: May 27, 2021 ordered by team name, last name, first name First name Surname Gender Agegroup Country Represented Desiree de Groen FEMALE F18-24 NLD (Netherlands) Deborah GILLARD FEMALE F18-24 BEL (Belgium) Paulien Poisquet FEMALE F18-24 BEL (Belgium) Lisa Roelofs FEMALE F18-24 NLD (Netherlands) Jana Roth FEMALE F18-24 DEU (Germany) Anna Schleifer FEMALE F18-24 DEU (Germany) AnouK van Kan FEMALE F18-24 NLD (Netherlands) Evelien Bourguignon FEMALE F25-29 NLD (Netherlands) Juliette Campione FEMALE F25-29 BEL (Belgium) SoetKin Devolder FEMALE F25-29 BEL (Belgium) Veerle Dijenborgh FEMALE F25-29 NLD (Netherlands) Julia FacKel FEMALE F25-29 DEU (Germany) Myrthe Geelen FEMALE F25-29 BEL (Belgium) Manon Ginesty FEMALE F25-29 FRA (France) Salome Hegi FEMALE F25-29 CHE (Switzerland) Lisa Käseberg FEMALE F25-29 DEU (Germany) Sophia Koch FEMALE F25-29 DEU (Germany) Fabienne Köster FEMALE F25-29 DEU (Germany) SasKia Kreisel FEMALE F25-29 NLD (Netherlands) Claire Laeven FEMALE F25-29 NLD (Netherlands) Aurore Lyon FEMALE F25-29 NLD (Netherlands) Stephanie Nicol FEMALE F25-29 CHE (Switzerland) Marjolein PluymaeKers FEMALE F25-29 NLD (Netherlands) Mirte Poort FEMALE F25-29 NLD (Netherlands) Lisa Ratz FEMALE F25-29 AUT (Austria) Tessa Schneider FEMALE F25-29 NLD (Netherlands) Sophie Smits FEMALE F25-29 NLD (Netherlands) 1 Startlist 2021 IRONMAN 5150 Maastricht - Limburg Last update: May 27, 2021 ordered by team name, last name, first name Valerie Snepvangers FEMALE F25-29 NLD (Netherlands) Evelyn -

Courier Gazette : October 3, 1939

he ourier azette ■ T E n tered u Second ClassC Mall Matter -G THREE CENTS A COPY Established January, 1846. By The Courier-Gazette, 4(5 Main St. Rockland, Maine, Tuesday, October 3/1939 V o lu m e 9 4 ....................Number 1 18. The Courier-Gazette [EDITORIAL] Annie Rhodes Spoke THREE-TIMES-AWEEK ROOSEVELT GAINS A BIT LIONS CAPTURE VINALHAVEN “THE BLACK CAT” Editor Local Teacher Tells Garden WM. O FULLER Because his foreign policies are much more to the liking Associate Editor of his party than his domestic policies, President Roosevelt Club Of Visit To Audu Zone Meeting Attracts 64 Of the Jungle Folk FRANK A. WINSLOW has gained 3 percent the past month as a third term prospect bon Camp Subscriptions 1300 per year payable This was fully expected as the result of the first war scare. In sdvance: single copies three cents, i This sentiment is strongest ln the South and in the West and An outstanding meeting of the — Emergency Drag Of Lobsters Advertising rates based upon circula tion and very reasonable Middle Atlantic States. In New England, according to the Rockland Garden Club was held NEWSPAPER HD3TORY Sept. 26, at Community Building, American Institute of Public Opinion 34 percent would vote The Vinalhaven Lions Club was Alec Baxter, John Tobey, L. E. The Rockland Oarette was estab with Mrs. Edward J. Hellier as hos lished ln 1846 In 1874 the Courier was for a third term and 66 percent against It. Other sections show Stimson. Michael E. Nagem, B. D. established and consolidated with the tess chairman Miss Caroline Ihost t0 some 47 vlsitin& Lions last these figures: Middle Atlantic, 46 percent for, 55 percent Larson. -

Dementia I N E U R O P E the Alzheimer Europe Magazine

Issue 2 December 2008 DEMENTIA I N E U R O P E THE ALZHEIMER EUROPE MAGAZINE “The fight of all Europeans against Alzheimer’s disease Katalin Levai, MEP, highlights the importance of the European Alzheimer's Alliance is a priority” Nicolas Sarkozy Alzheimer's associations throughout Europe celebrate World Alzheimer's Day Jan Tadeusz Masiel, MEP, talks about the situation in Poland for people with dementia ACT NOW Remember those who cannot 6.1 million people have dementia in Europe THE TIME TO ACT IS NOW MAKE DEMENTIA A EUROPEAN PRIORITY DEMENTIA Issue 2 IN EUROPE December 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE ALZHEIMER EUROPE MAGAZINE 04 Welcome 28 National dementia strategies By Maurice O’Connell, A snapshot of the status of national dementia Chair of Alzheimer Europe strategies within Europe 30 The view from Poland Prioritising dementia Jan Tadeusz Masiel, MEP, talks of the challenges faced by people with dementia and 06 Working together towards a better their carers understanding of dementia Alzheimer Europe reflects on the aims of the 32 Confronting double discrimination European Collaboration on Dementia project Roger Newman and Bill Cashman talk about and talks with Dianne Gove about the social discrimination, inclusion and diversity in the care recommendations context of people with dementia and their carers 09 Fighting dementia together Alzheimer Europe speaks with Katalin Levai, 34 Policy overview MEP A roundup of policy developments in the EU Alzheimer Europe Board 10 36 Learning from each other: Developing the European Pact of Maurice -

Beyond Priesthood Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche Und Vorarbeiten

Beyond Priesthood Religionsgeschichtliche Versuche und Vorarbeiten Herausgegeben von Jörg Rüpke und Christoph Uehlinger Band 66 Beyond Priesthood Religious Entrepreneurs and Innovators in the Roman Empire Edited by Richard L. Gordon, Georgia Petridou, and Jörg Rüpke ISBN 978-3-11-044701-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-044818-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-044764-4 ISSN 0939-2580 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2017 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com TableofContents Acknowledgements VII Bibliographical Note IX List of Illustrations XI Notes on the Contributors 1 Introduction 5 Part I: Innovation: Forms and Limits Jörg Rüpke and FedericoSantangelo Public priests and religious innovation in imperial Rome 15 Jan N. Bremmer Lucian on Peregrinus and Alexander of Abonuteichos: Asceptical viewoftwo religious entrepreneurs 49 Nicola Denzey Lewis Lived Religion amongsecond-century ‘Gnostic hieratic specialists’ 79 AnneMarie Luijendijk On and beyond -

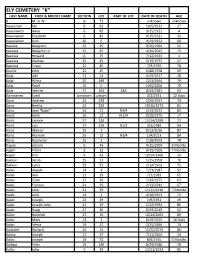

Ely Cemetery "K" Last Name First & Middle Name Section Lot Part of Lot Date of Death Age K M

ELY CEMETERY "K" LAST NAME FIRST & MIDDLE NAME SECTION LOT PART OF LOT DATE OF DEATH AGE K M. or W. 6 71 unknown unknown Kaasainen Ida 6 63 10/5/1912 27 Kaasalainen Anna 6 83 9/15/1921 4 Kaasalainen Elizabeth 6 83 9/15/1921 32 Kaasalainen John 20 6 4/29/1953 68 Kaatala Benjamin 25 45 9/26/1969 52 Kaatiala Benjamin Jr. 25 45 4/10/2015 73 Kaatiala Howard 6 75 7/12/1925 1 Kaatiala Idamae 25 45 3/19/1975 57 Kaatiala Susan 25 45 7/9/1970 78 Kaatila John 25 45 6/28/1958 69 Kaija Ade 11 14 4/19/1927 48 Kaija Hilma 25 189 12/3/1964 79 Kaija Pearl 10 6 10/6/2006 79 Kaija Werner 27 165 S&S 8/19/1981 63 Kainnianen Evert unknown unkwn 4/1/1921 12 Days Kainz Andrew 22 229 2/20/1957 74 Kainz Bertha 22 229 10/16/1971 81 Kainz Ione "Babe" 26 12 N3/4 5/19/2012 83 Kainz Keith 26 12 N 3/4 9/28/1970 17 Kainz Lenore 27 126 11/14/1999 77 Kainz Leo 27 126 N1/2 3/1/1989 69 Kainz Marion 25 2 8/13/2016 87 Kainz Norman 26 12 N3/4 1/4/2013 84 Kainz Raymond 25 2 1/18/2002 78 Kajute Johann 6 46 4/15/1904 4 Months Kajuti Infant 9 33 9/20/1900 7 Months Kajuti Erik 9 43 10/24/1900 33 Kakkuri Jacob 25 51 12/5/1958 70 Kakkuri Lydia 25 51 2/14/1963 73 Kalan Angela 14 3 7/23/1987 92 Kalan Ann 21 29 7/3/1983 65 Kalan Clare 27 36 7/24/1975 63 Kalan Frances 21 29 2/13/1944 67 Kalan John 21 29 11/22/1918 7 Months Kalan John 14 1 4/18/1953 72 Kalan Joseph 21 29 1/9/1931 49 Kalan Joseph John 21 29 1/12/1994 86 Kalan Kraig 27 36 8/29/2019 52 Kalan Rudolph 27 36 10/24/2003 89 Kalan Mary 14 1 8/29/1925 18 Days Kalan Verna 19 37 2/25/1996 74 Kalander Richard 26 16 11/22/1974 80 Kalata Joseph 17 37 7/11/1964 24 Kalcic Joseph 16 72 8/6/1910 5 Months Kalkaja Peter 19 136 8/29/1946 78 Kallio John 5 29 12/21/1933 85 LAST NAME FIRST & MIDDLE NAME SECTION LOT PART OF LOT DATE OF DEATH AGE Kallio Loviisa 5 29 10/23/1924 77 Kalouski John 9 49 9/1/1900 9 Kalovski Elizabeth 8 35 3/13/1914 62 Kammunen Jack 11 44 12/20/1939 68 Kalsich John Jr. -

Parcel Numbers

AddressStatus AddressType Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole for RV Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole for RV Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole for RV Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active Temporary Power Pole General Active <Null> Active <Null> Active Single Family Location Active <Null> Active <Null> Active <Null> Active <Null> Active Single Family Location Active Commercial Location Active Single Family Location Active <Null> Active <Null> Active Commercial Location Active <Null> Active Single Family Location Active Single Family Location Active <Null> Active