Generating and Organizing Variety in the Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 148.Pmd

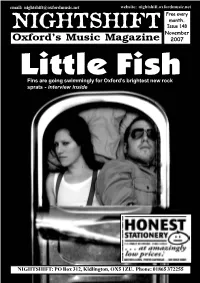

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 148 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 Little Fish Fins are going swimmingly for Oxford’s brightest new rock sprats - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] AS HAS BEEN WIDELY Oxford, with sold-out shows by the REPORTED, RADIOHEAD likes of Witches, Half Rabbits and a released their new album, `In special Selectasound show at the Rainbows’ as a download-only Bullingdon featuring Jaberwok and album last month with fans able to Mr Shaodow. The Castle show, pay what they wanted for the entitled ‘The Small World Party’, abum. With virtually no advance organised by local Oxjam co- press or interviews to promote the ordinator Kevin Jenkins, starts at album, `In Rainbows’ was reported midday with a set from Sol Samba to have sold over 1,500,000 copies as well as buskers and street CSS return to Oxford on Tuesday 11th December with a show at the in its first week. performers. In the afternoon there is Oxford Academy, as part of a short UK tour. The Brazilian elctro-pop Nightshift readers might remember a fashion show and auction featuring stars are joined by the wonderful Metronomy (recent support to Foals) that in March this year local act clothes from Oxfam shops, with the and Joe Lean and the Jing Jang Jong. Tickets are on sale now, priced The Sad Song Co. - the prog-rock main concert at 7pm featuring sets £15, from 0844 477 2000 or online from wegottickets.com solo project of Dive Dive drummer from Cyberscribes, Mr Shaodow, Nigel Powell - offered a similar deal Brickwork Lizards and more. -

BOY S GOLD Mver’S Windsong M If for RCA Distribim

Lion, joe f AND REYNOLDS/ BOY S GOLD mver’s Windsong M if For RCA Distribim ARM Rack Jobbe Confab cercise In Commi i cation ista Celebrates 'st Year ith Convention, Concert tal’s Private Stc ijoys 1st Birthd , usexpo Makes I : TED NUGENFS HIGH WIRED ACT. Ted Nugent . Some claim he invented high energy. Audiences across the country agree he does it best. With his music, his songs and his very plugged-in guitar, Ted Nugent’s new album, en- titled “Ted Nugent,” raises the threshold of high energy rock and roll. Ted Nugent. High high volume, high quality. 0n Epic Records and Tapes. High Energy, Zapping Cross-Country On Tour September 18 St. Louis, Missouri; September 19 Chicago, Illinois; September 20 Columbus, Ohio; September 23 Pitts, Penn- sylvania; September 26 Charleston, West Virginia; September 27 Norfolk, Virginia; October 1 Johnson City, Tennessee; Octo- ber 2 Knoxville, Tennessee; October 4 Greensboro, North Carolina; October 5 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; October 8 Louisville, x ‘ Kentucky; October 11 Providence, Rhode Island; October 14 Jonesboro, Arkansas; October 15 Joplin, Missouri; October 17 Lincoln, Nebraska; October 18 Kansas City, Missouri; October 21 Wichita, Kansas; October 24 Tulsa, Oklahoma -j 1 THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC-RECORD WEEKLY C4SHBCX VOLUME XXXVII —NUMBER 20 — October 4. 1975 \ |GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW cashbox editorial Executive Vice President Editorial DAVID BUDGE Editor In Chief The Superbullets IAN DOVE East Coast Editorial Director Right now there are a lot of superbullets in the Cash Box Top 1 00 — sure evidence that the summer months are over and the record industry is gearing New York itself for the profitable dash towards the Christmas season. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period. -

Icebreaker: Apollo

Icebreaker: Apollo Start time: 7.30pm Running time: 2 hours 20 minutes with interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Martin Aston looks into the history behind Apollo alongside other works being performed by eclectic ground -breaking composers. When man first stepped on the moon, on July 20th, 1969, ‘ambient music’ had not been invented. The genre got its name from Brian Eno after he’d released the album Discreet Music in 1975, alluding to a sound ‘actively listened to with attention or as easily ignored, depending on the choice of the listener,’ and which existed on the, ‘cusp between melody and texture.’ One small step, then, for the categorisation of music, and one giant leap for Eno’s profile, which he expanded over a series of albums (and production work) both song-based and ambient. In 1989, assisted by his younger brother Roger (on piano) and Canadian producer Daniel Lanois, Eno provided the soundtrack for Al Reinert’s documentary Apollo: the trio’s exquisitely drifting, beatific sound profoundly captured the mood of deep space, the suspension of gravity and the depth of tranquillity and awe that NASA’s astronauts experienced in the missions that led to Apollo 11’s Neil Armstrong taking that first step on the lunar surface. ‘One memorable image in the film was a bright white-blue moon, and as the rocket approached, it got much darker, and you realised the moon was above you,’ recalls Roger Eno. ‘That feeling of immensity was a gift: you just had to accentuate the majesty.’ In 2009, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of that epochal trip, Tim Boon, head of research at the Science Museum in London, conceived the idea of a live soundtrack of Apollo to accompany Reinert’s film (which had been re-released in 1989 in a re-edited form, and retitled For All Mankind. -

Philip Glass

DEBARTOLO PERFORMING ARTS CENTER PRESENTING SERIES PRESENTS MUSIC BY PHILIP GLASS IN A PERFORMANCE OF AN EVENING OF CHAMBER MUSIC WITH PHILIP GLASS TIM FAIN AND THIRD COAST PERCUSSION MARCH 30, 2019 AT 7:30 P.M. LEIGHTON CONCERT HALL Made possible by the Teddy Ebersol Endowment for Excellence in the Performing Arts and the Gaye A. and Steven C. Francis Endowment for Excellence in Creativity. PROGRAM: (subject to change) PART I Etudes 1 & 2 (1994) Composed and Performed by Philip Glass π There were a number of special events and commissions that facilitated the composition of The Etudes by Philip Glass. The original set of six was composed for Dennis Russell Davies on the occasion of his 50th birthday in 1994. Chaconnes I & II from Partita for Solo Violin (2011) Composed by Philip Glass Performed by Tim Fain π I met Tim Fain during the tour of “The Book of Longing,” an evening based on the poetry of Leonard Cohen. In that work, all of the instrumentalists had solo parts. Shortly after that tour, Tim asked me to compose some solo violin music for him. I quickly agreed. Having been very impressed by his ability and interpretation of my work, I decided on a seven-movement piece. I thought of it as a Partita, the name inspired by the solo clavier and solo violin music of Bach. The music of that time included dance-like movements, often a chaconne, which represented the compositional practice. What inspired me about these pieces was that they allowed the composer to present a variety of music composed within an overall structure. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

The Underrepresentation of Female Personalities in EDM

The Underrepresentation of Female Personalities in EDM A Closer Look into the “Boys Only”-Genre DANIEL LUND HANSEN SUPERVISOR Daniel Nordgård University of Agder, 2017 Faculty of Fine Art Department of Popular Music There’s no language for us to describe women’s experiences in electronic music because there’s so little experience to base it on. - Frankie Hutchinson, 2016. ABSTRACT EDM, or Electronic Dance Music for short, has become a big and lucrative genre. The once nerdy and uncool phenomenon has become quite the profitable business. Superstars along the lines of Calvin Harris, David Guetta, Avicii, and Tiësto have become the rock stars of today, and for many, the role models for tomorrow. This is though not the case for females. The British magazine DJ Mag has an annual contest, where listeners and fans of EDM can vote for their favorite DJs. In 2016, the top 100-list only featured three women; Australian twin duo NERVO and Ukrainian hardcore DJ Miss K8. Nor is it easy to find female DJs and acts on the big electronic festival-lineups like EDC, Tomorrowland, and the Ultra Music Festival, thus being heavily outnumbered by the go-go dancers on stage. Furthermore, the commercial music released are almost always by the male demographic, creating the myth of EDM being an industry by, and for, men. Also, controversies on the new phenomenon of ghost production are heavily rumored among female EDM producers. It has become quite clear that the EDM industry has a big problem with the gender imbalance. Based on past and current events and in-depth interviews with several DJs, both female and male, this paper discusses the ongoing problems women in EDM face. -

Third Coast Percussion

Third Coast Percussion Start time: 8pm Running time: 1 hour 45 minutes – including interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Ruth Kilpatrick delves into tonight’s programme, and the ensemble’s passion for collaborative new composition. Chicago’s Third Coast Percussion is a Grammy Award winning ensemble, world renowned for their impressive arrangements of classic works, powerful new pieces and always inspiring performances. This concert sees them at the Barbican for the first time, with a programme celebrating the wealth of possibility that comes from open, honest collaboration. Featuring four UK premieres, the evening begins with Philip Glass’s Madeira River; re-named after the Amazon River and its tributaries by Brazilian group Uakti for their own custom-made instruments back in 1999. For their 2017 album Paddle To The Sea, Third Coast Percussion took inspiration from both the original piano works and the Uakti arrangement, to create their own six-minute piece. Perhaps their most well-known work to date, the classically trained quartet released an album of Steve Reich’s works in celebration of his 80th birthday in 2016, on Cedille Records, winning the Grammy for Best Chamber Music / Small Ensemble Performance. Reich’s influence on modern composition is vast; with Mallet Quartet offering a more melodic take on his perhaps more minimalist past. Scored for two marimbas and two vibraphones, the three movements over fifteen-minutes offer rhythmic energy and room for reflection all at once. The last piece of the first half is Perpetulum; composed for and in collaboration with Third Coast Percussion by Philip Glass. -

Roxy Music to Play a Day on the Green with Original Line up Including the Legendary Bryan Ferry

Media Release: Thursday 18 th November ROXY MUSIC TO PLAY A DAY ON THE GREEN WITH ORIGINAL LINE UP INCLUDING THE LEGENDARY BRYAN FERRY With support from Nathan Haines Roundhouse Entertainment and Andrew McManus Presents is proud to announce that Roxy Music, consisting of vocalist Bryan Ferry, guitarist Phil Manzanera, saxophonist Andy Mackay and the great Paul Thompson on drums, are coming to New Zealand for one A Day On The Green show only at Villa Maria Estate Winery on Sunday 6 th March. Roxy Music will perform material from their entire catalogue including such hits as, Dance Away , Avalon , Let's Stick Together, Take A Chance With Me , Do the Strand , Angel Eyes , Oh Yeah , In the Midnight Hour , Jealous Guy, Love Is The Drug , More Than This and many more. Distinguished by their visual and musical sophistication and their preoccupation with style and glamour Roxy Music were highly influential, as leading proponents of the more experimental element of glam rock as well as a significant influence on early English punk music. They also provided a model for many new wave acts and the experimental electronic groups of the early 1980s. In 2004, Rolling Stone Magazine ranked Roxy Music on its list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time and the band are regarded as one of the most influential art-rock bands in music history. Roxy Music exploded onto the scene in 1972 with their progressive self-titled debut album. The sound challenged the constraints of pop music and was lauded by critics and popular among fans, peaking at #4 on the UK album charts. -

Rethinking Minimalism: at the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism

Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter Shelley A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2013 Reading Committee Jonathan Bernard, Chair Áine Heneghan Judy Tsou Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Music Theory ©Copyright 2013 Peter Shelley University of Washington Abstract Rethinking Minimalism: At the Intersection of Music Theory and Art Criticism Peter James Shelley Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. Jonathan Bernard Music Theory By now most scholars are fairly sure of what minimalism is. Even if they may be reluctant to offer a precise theory, and even if they may distrust canon formation, members of the informed public have a clear idea of who the central canonical minimalist composers were or are. Sitting front and center are always four white male Americans: La Monte Young, Terry Riley, Steve Reich, and Philip Glass. This dissertation negotiates with this received wisdom, challenging the stylistic coherence among these composers implied by the term minimalism and scrutinizing the presumed neutrality of their music. This dissertation is based in the acceptance of the aesthetic similarities between minimalist sculpture and music. Michael Fried’s essay “Art and Objecthood,” which occupies a central role in the history of minimalist sculptural criticism, serves as the point of departure for three excursions into minimalist music. The first excursion deals with the question of time in minimalism, arguing that, contrary to received wisdom, minimalist music is not always well understood as static or, in Jonathan Kramer’s terminology, vertical. The second excursion addresses anthropomorphism in minimalist music, borrowing from Fried’s concept of (bodily) presence. -

Roxy Music in 1972: Phil Manzanera, Bryan Ferry, Andy Mackay, Brian Eno, Rik Kenton, and Paul Thompson (From Le )

Roxy Music in 1972: Phil Manzanera, Bryan Ferry, Andy Mackay, Brian Eno, Rik Kenton, and Paul Thompson (from le ) > > Roxy 20494_RNRHF_Text_Rev0_54-120.pdfMusic 9 3/5/19 10:32 AM A THE ICONOCLASTIC BAND’S MUSIC CHANGED DRASTICALLY WHILE BALANCING FINE TASTE WITH MAVERICK STYLE BY JIM FARBER n what universe does the story of Roxy Mu- Since the group formed in 1972, Roxy messed with sic make sense? They began with a sound everyone’s notion of what music should sound like, as fired by cacophonous outbursts and wild well as how a band should present itself. The songs on aectations, only to evolve into one of the their first two albums often landed like punchlines, most finely controlled and heartfelt bands of fired by guitar, synth, and sax solos as exaggerated as all time. On the one hand, they lampooned cartoons. It was a sonic pastiche of the most anarchic, glamour, romance, and style, while on the gleeful, and sublime kind, created by a cast of inspired other epitomizing their highest expressions. And strays. And, amid their early ranks were two players – while they drew on common genres – including Bryan Ferry and Brian Eno – who would come to stand glam, free jazz, and art rock – they suered none of among music’s most creative forces. Given the scope of their clichés. Oh, and somewhere along the way, they the pair’s talents, it’s no surprise Roxy could contain Imade oboe solos a thing. them both for only two years. 20494_RNRHF_Text_Rev0_54-120.pdf 10 3/5/19 10:32 AM 20494_RNRHF_Text_Rev0_54-120.pdf 11 3/5/19 10:32 AM Opposite page: Bryan Ferry in the studio, 1971.