Spatio-Temporal Suspension and Imagery in Popular Music Recordings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Issue 148.Pmd

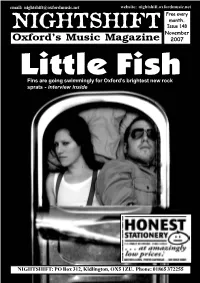

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 148 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 Little Fish Fins are going swimmingly for Oxford’s brightest new rock sprats - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] AS HAS BEEN WIDELY Oxford, with sold-out shows by the REPORTED, RADIOHEAD likes of Witches, Half Rabbits and a released their new album, `In special Selectasound show at the Rainbows’ as a download-only Bullingdon featuring Jaberwok and album last month with fans able to Mr Shaodow. The Castle show, pay what they wanted for the entitled ‘The Small World Party’, abum. With virtually no advance organised by local Oxjam co- press or interviews to promote the ordinator Kevin Jenkins, starts at album, `In Rainbows’ was reported midday with a set from Sol Samba to have sold over 1,500,000 copies as well as buskers and street CSS return to Oxford on Tuesday 11th December with a show at the in its first week. performers. In the afternoon there is Oxford Academy, as part of a short UK tour. The Brazilian elctro-pop Nightshift readers might remember a fashion show and auction featuring stars are joined by the wonderful Metronomy (recent support to Foals) that in March this year local act clothes from Oxfam shops, with the and Joe Lean and the Jing Jang Jong. Tickets are on sale now, priced The Sad Song Co. - the prog-rock main concert at 7pm featuring sets £15, from 0844 477 2000 or online from wegottickets.com solo project of Dive Dive drummer from Cyberscribes, Mr Shaodow, Nigel Powell - offered a similar deal Brickwork Lizards and more. -

BOY S GOLD Mver’S Windsong M If for RCA Distribim

Lion, joe f AND REYNOLDS/ BOY S GOLD mver’s Windsong M if For RCA Distribim ARM Rack Jobbe Confab cercise In Commi i cation ista Celebrates 'st Year ith Convention, Concert tal’s Private Stc ijoys 1st Birthd , usexpo Makes I : TED NUGENFS HIGH WIRED ACT. Ted Nugent . Some claim he invented high energy. Audiences across the country agree he does it best. With his music, his songs and his very plugged-in guitar, Ted Nugent’s new album, en- titled “Ted Nugent,” raises the threshold of high energy rock and roll. Ted Nugent. High high volume, high quality. 0n Epic Records and Tapes. High Energy, Zapping Cross-Country On Tour September 18 St. Louis, Missouri; September 19 Chicago, Illinois; September 20 Columbus, Ohio; September 23 Pitts, Penn- sylvania; September 26 Charleston, West Virginia; September 27 Norfolk, Virginia; October 1 Johnson City, Tennessee; Octo- ber 2 Knoxville, Tennessee; October 4 Greensboro, North Carolina; October 5 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; October 8 Louisville, x ‘ Kentucky; October 11 Providence, Rhode Island; October 14 Jonesboro, Arkansas; October 15 Joplin, Missouri; October 17 Lincoln, Nebraska; October 18 Kansas City, Missouri; October 21 Wichita, Kansas; October 24 Tulsa, Oklahoma -j 1 THE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC-RECORD WEEKLY C4SHBCX VOLUME XXXVII —NUMBER 20 — October 4. 1975 \ |GEORGE ALBERT President and Publisher MARTY OSTROW cashbox editorial Executive Vice President Editorial DAVID BUDGE Editor In Chief The Superbullets IAN DOVE East Coast Editorial Director Right now there are a lot of superbullets in the Cash Box Top 1 00 — sure evidence that the summer months are over and the record industry is gearing New York itself for the profitable dash towards the Christmas season. -

IPG Spring 2020 Rock Pop and Jazz Titles

Rock, Pop, and Jazz Titles Spring 2020 {IPG} That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde Daryl Sanders Summary That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound is the definitive treatment of Bob Dylan’s magnum opus, Blonde on Blonde , not only providing the most extensive account of the sessions that produced the trailblazing album, but also setting the record straight on much of the misinformation that has surrounded the story of how the masterpiece came to be made. Including many new details and eyewitness accounts never before published, as well as keen insight into the Nashville cats who helped Dylan reach rare artistic heights, it explores the lasting impact of rock’s first double album. Based on exhaustive research and in-depth interviews with the producer, the session musicians, studio personnel, management personnel, and others, Daryl Sanders Chicago Review Press chronicles the road that took Dylan from New York to Nashville in search of “that thin, wild mercury sound.” 9781641602730 As Dylan told Playboy in 1978, the closest he ever came to capturing that sound was during the Blonde on Pub Date: 5/5/20 On Sale Date: 5/5/20 Blonde sessions, where the voice of a generation was backed by musicians of the highest order. $18.99 USD Discount Code: LON Contributor Bio Trade Paperback Daryl Sanders is a music journalist who has worked for music publications covering Nashville since 1976, 256 Pages including Hank , the Metro, Bone and the Nashville Musician . He has written about music for the Tennessean , 15 B&W Photos Insert Nashville Scene , City Paper (Nashville), and the East Nashvillian . -

In the Studio: the Role of Recording Techniques in Rock Music (2006)

21 In the Studio: The Role of Recording Techniques in Rock Music (2006) John Covach I want this record to be perfect. Meticulously perfect. Steely Dan-perfect. -Dave Grohl, commencing work on the Foo Fighters 2002 record One by One When we speak of popular music, we should speak not of songs but rather; of recordings, which are created in the studio by musicians, engineers and producers who aim not only to capture good performances, but more, to create aesthetic objects. (Zak 200 I, xvi-xvii) In this "interlude" Jon Covach, Professor of Music at the Eastman School of Music, provides a clear introduction to the basic elements of recorded sound: ambience, which includes reverb and echo; equalization; and stereo placement He also describes a particularly useful means of visualizing and analyzing recordings. The student might begin by becoming sensitive to the three dimensions of height (frequency range), width (stereo placement) and depth (ambience), and from there go on to con sider other special effects. One way to analyze the music, then, is to work backward from the final product, to listen carefully and imagine how it was created by the engineer and producer. To illustrate this process, Covach provides analyses .of two songs created by famous producers in different eras: Steely Dan's "Josie" and Phil Spector's "Da Doo Ron Ron:' Records, tapes, and CDs are central to the history of rock music, and since the mid 1990s, digital downloading and file sharing have also become significant factors in how music gets from the artists to listeners. Live performance is also important, and some groups-such as the Grateful Dead, the Allman Brothers Band, and more recently Phish and Widespread Panic-have been more oriented toward performances that change from night to night than with authoritative versions of tunes that are produced in a recording studio. -

Icebreaker: Apollo

Icebreaker: Apollo Start time: 7.30pm Running time: 2 hours 20 minutes with interval Please note all timings are approximate and subject to change Martin Aston looks into the history behind Apollo alongside other works being performed by eclectic ground -breaking composers. When man first stepped on the moon, on July 20th, 1969, ‘ambient music’ had not been invented. The genre got its name from Brian Eno after he’d released the album Discreet Music in 1975, alluding to a sound ‘actively listened to with attention or as easily ignored, depending on the choice of the listener,’ and which existed on the, ‘cusp between melody and texture.’ One small step, then, for the categorisation of music, and one giant leap for Eno’s profile, which he expanded over a series of albums (and production work) both song-based and ambient. In 1989, assisted by his younger brother Roger (on piano) and Canadian producer Daniel Lanois, Eno provided the soundtrack for Al Reinert’s documentary Apollo: the trio’s exquisitely drifting, beatific sound profoundly captured the mood of deep space, the suspension of gravity and the depth of tranquillity and awe that NASA’s astronauts experienced in the missions that led to Apollo 11’s Neil Armstrong taking that first step on the lunar surface. ‘One memorable image in the film was a bright white-blue moon, and as the rocket approached, it got much darker, and you realised the moon was above you,’ recalls Roger Eno. ‘That feeling of immensity was a gift: you just had to accentuate the majesty.’ In 2009, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of that epochal trip, Tim Boon, head of research at the Science Museum in London, conceived the idea of a live soundtrack of Apollo to accompany Reinert’s film (which had been re-released in 1989 in a re-edited form, and retitled For All Mankind. -

Mediated Music Makers. Constructing Author Images in Popular Music

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in auditorium XII, on the 10th of November, 2007 at 10 o’clock. Laura Ahonen Mediated music makers Constructing author images in popular music Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. © Laura Ahonen Layout: Tiina Kaarela, Federation of Finnish Learned Societies ISBN 978-952-99945-0-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-952-10-4117-4 (PDF) Finnish Society for Ethnomusicology Publ. 16. ISSN 0785-2746. Contents Acknowledgements. 9 INTRODUCTION – UNRAVELLING MUSICAL AUTHORSHIP. 11 Background – On authorship in popular music. 13 Underlying themes and leading ideas – The author and the work. 15 Theoretical framework – Constructing the image. 17 Specifying the image types – Presented, mediated, compiled. 18 Research material – Media texts and online sources . 22 Methodology – Social constructions and discursive readings. 24 Context and focus – Defining the object of study. 26 Research questions, aims and execution – On the work at hand. 28 I STARRING THE AUTHOR – IN THE SPOTLIGHT AND UNDERGROUND . 31 1. The author effect – Tracking down the source. .32 The author as the point of origin. 32 Authoring identities and celebrity signs. 33 Tracing back the Romantic impact . 35 Leading the way – The case of Björk . 37 Media texts and present-day myths. .39 Pieces of stardom. .40 Single authors with distinct features . 42 Between nature and technology . 45 The taskmaster and her crew. -

BBC Radio 2 | Fri 01 Jan - Sat 31 Dec 2016 Between 00:00 and 24:00 Compared to 06 Jan 2017 Between 00:00 and 24:00

BBC Radio 2 | Fri 01 Jan - Sat 31 Dec 2016 between 00:00 and 24:00 Compared to 06 Jan 2017 between 00:00 and 24:00 Pos LW Artist Title Company Owner R. date Plays LW plays Trend 1 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling RCA SME 06 May 2016 155 New -- 2 Lukas Graham 7 Years Warner Bros R.. WMG 23 Jun 2015 140 New -- 3 DNCE Cake By The Ocean Island UMG 15 Sep 2015 131 New -- 4 Coldplay Hymn For The Weekend Parlophone WMG 04 Dec 2015 108 New -- 5 Shadows, The Foot Tapper Columbia SME - 106 New -- 6 Travis 3 Miles High Caroline Inte.. UMG 26 Feb 2016 103 New -- 7 ABC Viva Love Virgin EMI UMG 08 Apr 2016 98 New -- 8 Sigma feat. Take That Cry 3beat Ind. 15 Jul 2016 97 New -- 9 Emeli Sandé Breathing Underwater Virgin EMI UMG 27 Oct 2016 95 New -- 9 Gwen Stefani Make Me Like You Interscope UMG 25 Mar 2016 95 New -- 9 Michael Bublé Nobody But Me Warner Bros R.. WMG 18 Aug 2016 95 New -- 12 ABC The Flames Of Desire Virgin EMI UMG 27 May 2016 94 New -- 12 Shaun Escoffery When The Love Is Gone Dome/MVKA Ind. 17 Jun 2016 94 New -- 12 Tom Odell Magnetised Columbia SME 14 Apr 2016 94 New -- 15 Jamie Lawson Cold In Ohio Atlantic WMG 16 Dec 2015 93 New -- 15 Joe & Jake You're Not Alone Sony CMG SME 23 Feb 2016 93 New -- 15 Rag'N'Bone Man Human Columbia SME 20 Jul 2016 93 New -- 18 Travis Animals Caroline Inte. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

The Underrepresentation of Female Personalities in EDM

The Underrepresentation of Female Personalities in EDM A Closer Look into the “Boys Only”-Genre DANIEL LUND HANSEN SUPERVISOR Daniel Nordgård University of Agder, 2017 Faculty of Fine Art Department of Popular Music There’s no language for us to describe women’s experiences in electronic music because there’s so little experience to base it on. - Frankie Hutchinson, 2016. ABSTRACT EDM, or Electronic Dance Music for short, has become a big and lucrative genre. The once nerdy and uncool phenomenon has become quite the profitable business. Superstars along the lines of Calvin Harris, David Guetta, Avicii, and Tiësto have become the rock stars of today, and for many, the role models for tomorrow. This is though not the case for females. The British magazine DJ Mag has an annual contest, where listeners and fans of EDM can vote for their favorite DJs. In 2016, the top 100-list only featured three women; Australian twin duo NERVO and Ukrainian hardcore DJ Miss K8. Nor is it easy to find female DJs and acts on the big electronic festival-lineups like EDC, Tomorrowland, and the Ultra Music Festival, thus being heavily outnumbered by the go-go dancers on stage. Furthermore, the commercial music released are almost always by the male demographic, creating the myth of EDM being an industry by, and for, men. Also, controversies on the new phenomenon of ghost production are heavily rumored among female EDM producers. It has become quite clear that the EDM industry has a big problem with the gender imbalance. Based on past and current events and in-depth interviews with several DJs, both female and male, this paper discusses the ongoing problems women in EDM face. -

The Xx Slipper Video - 'On Hold'

28-11-2016 16:31 CET The xx slipper video - 'On Hold' The xx slipper video regissert av Alasdair McLellan Se video HER - Limited Edition ‘On Hold’ 7” vinyl tilgjengelig nå. - 7 kvelder på London’s O2 Academy Brixton utsolgt på 1 dag. Mandag 28.november 2016 – The xx slipper i dag video for ‘On Hold’, den første singelen fra trioens etterlengtede tredje album ‘I See You’. Videoen ble skutt i Marfa, Texas, hvor bandet skrev og spilte inn deler av albumet ‘I See You’, og er regissert av den anerkjente filmskaperen og fotografen Alasdair McLellan. Se video ‘On Hold’ HER The xx sier:“Today we get to share our new video for ‘On Hold’ with you! The video is directed by the brilliant Alasdair McLellan, whose work we all adore... It was filmed in Marfa, Texas, a very special place to us, where we wrote and recorded some of our new album. We have a lot of love and respect for the people of the USA, having played hundreds of shows across the country over the past years. We hope this video reflects just some of the warmth and acceptance we have encountered there.” The xx annonserer også at ‘On Hold’ slippes på en helt spesiell limitert 7” vinyl. Den limiterte 7" vinylen. Denne kan forhåndsbestilles hos oss nå. I tillegg kan The xx dele at de har satt ny salgsrekord på Londons O2 Academy Brixton. Trioen tar over den legendariske konsertscenen 8-15 mars, og spiller for totalt 35.000 personer over syv kvelder. Alle billettene forsvant på rekordfart. -

THE BIRTH of HARD ROCK 1964-9 Charles Shaar Murray Hard Rock

THE BIRTH OF HARD ROCK 1964-9 Charles Shaar Murray Hard rock was born in spaces too small to contain it, birthed and midwifed by youths simultaneously exhilarated by the prospect of emergent new freedoms and frustrated by the slow pace of their development, and delivered with equipment which had never been designed for the tasks to which it was now applied. Hard rock was the sound of systems under stress, of energies raging against confnement and constriction, of forces which could not be contained, merely harnessed. It was defned only in retrospect, because at the time of its inception it did not even recognise itself. The musicians who played the frst ‘hard rock’ and the audiences who crowded into the small clubs and ballrooms of early 1960s Britain to hear them, thought they were playing something else entirely. In other words, hard rock was – like rock and roll itself – a historical accident. It began as an earnest attempt by British kids in the 1960s, most of whom were born in the 1940s and raised and acculturated in the 1950s, to play American music, drawing on blues, soul, R&B, jazz and frst-generation rock, but forced to reinvent both the music, and its world, in their own image, resulting in something entirely new. However, hard rock was neither an only child, nor born fully formed. It shared its playpen, and many of its toys, with siblings (some named at the time and others only in retrospect) like R&B, psychedelia, progressive rock, art-rock and folk-rock, and it emerged only gradually from the intoxicating stew of myriad infuences that formed the musical equivalent of primordial soup in the uniquely turbulent years of the second (technicolour!) half of the 1960s. -

Seven Nation Army Lyrics Pdf

Seven nation army lyrics pdf Continue 2003 single The White Stripes Seven Nation ArmySingle by The White Stripesfrom the album ElephantB-sideGood to MeReleasedMarch 7, 2003StudioTo Rag 2002 (London)Genre Alternative Rock Garage Rock Length3:52Label XL V2 Third Man Author Songs (s) Jack WhiteProducer (s) Jack WhiteThe White band singles chronology Candy Cane Children (2002) Seven Nation Army (2003) I Just Don't Know What to Do With Myself (2003) Music video Seven Nation Army on YouTube Seven Nation Army - song of American rock duo White Stripes. It debuted on their fourth studio album, Elephant, and was released by XL Recordings and V2 Records in March 2003 as the lead single, through 7-inch vinyl and CD formats. Written and produced by Jack White, the song consists of distorted vocals, a simple drum rhythm and a bass-like riff created by playing guitar through the step-change effect. The song was written in the charts of many countries, and its success contributed to the popularity of the White Stripes and the movement of the revival of garage rock. In addition to praising his riff and drumbeat, critics rated Seven Nation Army as one of the best songs of the 2000s decade. It won Best Rock Song at the 46th Annual Grammy Awards, and the music video for director Alex and Martin's song won Best Editing in a Video at the 2003 MTV Video Music Awards. Seven Nation Army became a sporting anthem, usually appearing in audience chants, in which a series of o sounds or the name of an athlete are sung to the tune of a riff of a song.