Amit Manger Phd-Sociology.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Micro Cottage and Small Entrepreneur Refinancing

l;4fy{ a}+s lnld6]8 != n3' 3/]n tyf ;fgf pBd shf{ s| g zfvf C0fLsf] gfd k||b]z s| g zfvf C0fLsf] gfd k||b]z . 1 Fikkal Sarita Pradhan 1 2101 JANAKPU CHAND TAILORS 2 2 Fikkal Navin Katuwal 1 2102 HETAUD RADHA SUPPLIERS Bagmati 3 Fikkal Rita Shrestha 1 2103 AAMCHO HIMAL FENCY KAPADA PASAL 1 4 Fikkal Pramesh Lamichhane 1 2104 SURKHET TIKA KHADYA TATHA KIRANAPASAL Karnali 5 RAJMARGA CHOWK KANKAI SUPPLIERS 1 2105 DHANGA KARUNA ELECTRONICS Sudurpashchim 6 Sindhuli unique electronic pasal 4 2106 DHANGA ANKIT NASTA PASAL Sudurpashchim 7 Sindhuli Kamal Bahadur khadka 5 2107 BUDIGAN TU FURNITURE UDHOG Sudurpashchim 8 Farsatikar New Kharel Order Suppliers 5 2108 BUDDHA SHUBHECHCHHA FANCY PASAL Gandaki 9 Taplejung Chandani Hotel 1 2109 TULSIPU NEW DANGI PLUMBINGSUPPLIERS 5 10 Taplejung Tej Bir Limbu 1 2110 HETAUD AMRITA KIRANA AND COLDSTORES Bagmati 11 Taplejung Dipak Gurung 1 2111 YASHOD SHUBHAM MOBILE CENTER 5 12 Taplejung Ganga Bahadur Limbu 1 2112 GADHI RAMU WORKSHOP 1 13 Taplejung Som Bimali 1 2113 DHANGA SANJAY AND YAMAN TRADERS Sudurpashchim 14 Taplejung Hari Kumar Limbu 1 2114 GOKULG G.N. ELECTRONICS AND MOBILECENTER Bagmati 15 Taplejung Chhowang Sherpa 1 2115 AAMCHO LOK BAHADUR KIRANA PASAL 1 16 Taplejung Gopal Neupane 1 2116 GHORAHI NEW SABINA HOTEL 5 17 Birauta Prashidddi Tours and Travels Pvt Ltd. Gandaki 2117 BUDIGAN NAUBIS GENERAL STORE Sudurpashchim 18 Chandragadi Sagarmatha Treders 1 2118 BIRATCH KANCHHA BAHUUDESHYAKRISHI FIRM 1 19 Chandragadi Hotel Grindland 1 2119 AAMCHO NANGANU NUYAHANG TRADERS 1 20 Chandragadi Bina books and Stationery 1 2120 AAMCHO SAKENWA PHALPHUL TA. -

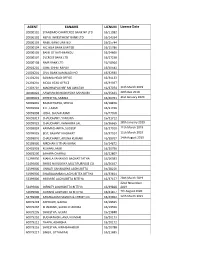

List of Active Agents

AGENT EANAME LICNUM License Date 20000101 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK NP LTD 16/11082 20000102 NEPAL INVESTMENT BANK LTD 16/14334 20000103 NABIL BANK LIMITED 16/15744 20000104 NIC ASIA BANK LIMITED 16/15786 20000105 BANK OF KATHMANDU 16/24666 20000107 EVEREST BANK LTD. 16/27238 20000108 NMB BANK LTD 16/18964 20901201 GIME CHHETRAPATI 16/30543 21001201 CIVIL BANK KAMALADI HO 16/32930 21101201 SANIMA HEAD OFFICE 16/34133 21201201 MEGA HEAD OFFICE 16/34037 21301201 MACHHAPUCHRE BALUWATAR 16/37074 11th March 2019 40000022 AAWHAN BAHUDAYSIYA SAHAKARI 16/35623 20th Dec 2019 40000023 SHRESTHA, SABINA 16/40761 31st January 2020 50099001 BAJRACHARYA, SHOVA 16/18876 50099003 K.C., LAXMI 16/21496 50099008 JOSHI, SHUVALAXMI 16/27058 50099017 CHAUDHARY, YAMUNA 16/31712 50099023 CHAUDHARY, KANHAIYA LAL 16/36665 28th January 2019 50099024 KARMACHARYA, SUDEEP 16/37010 11th March 2019 50099025 BIST, BASANTI KADAYAT 16/37014 11th March 2019 50099026 CHAUDHARY, ARUNA KUMARI 16/38767 14th August 2019 50199000 NIRDHAN UTTHAN BANK 16/14872 50401003 KISHAN LAMKI 16/20796 50601200 SAHARA CHARALI 16/22807 51299000 MAHILA SAHAYOGI BACHAT TATHA 16/26083 51499000 SHREE NAVODAYA MULTIPURPOSE CO 16/26497 51599000 UNNATI SAHAKARYA LAGHUBITTA 16/28216 51999000 SWABALAMBAN LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/33814 52399000 MIRMIRE LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/37157 28th March 2019 22nd November 52499000 INFINITY LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/39828 2019 52699000 GURANS LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/41877 7th August 2020 52799000 KANAKLAXMI SAVING & CREDIT CO. 16/43902 12th March 2021 60079203 ADHIKARI, GAJRAJ -

Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal

UNEQUAL CITIZENS UNEQUAL37966 Public Disclosure Authorized CITIZENS Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Caste and Ethnic Exclusion Gender, THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development SUMMARY BANK The World Bank DFID Nepal Nepal Office P.O. Box 106 P.O. Box 798 Kathmandu, Nepal Yak and Yeti Hotel Tel.: 5542980 Complex Fax: 5542979 Durbar Marg Public Disclosure Authorized Kathmandu, Nepal Tel.: 4226792, 4226793 E-mail Fax: 4225112 [email protected] Websites www.worldbank.org.np, Website www.bishwabank.org.np www.dfid.gov.uk Public Disclosure Authorized DFID Development International Department For ISBN 99946-890-0-2 9 799994 689001 > BANK WORLD THE Public Disclosure Authorized A Kathmandu businessman gets his shoes shined by a Sarki. The Sarkis belong to the leatherworker subcaste of Nepal’s Dalit or “low caste” community. Although caste distinctions and the age-old practices of “untouchability” are less rigid in urban areas, the deeply entrenched caste hierarchy still limits the life chances of the 13 percent of Nepal’s population who belong to the Dalit caste group. UNEQUAL CITIZENS Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal SUMMARY THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development BANK THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development BANK The World Bank DFID Nepal Nepal Office P.O. Box 106 P.O. Box 798 Kathmandu, Nepal Yak and Yeti Hotel Complex Tel.: 5542980 Durbar Marg Fax: 5542979 Kathmandu, Nepal Tel.: 4226792, 4226793 E-mail Fax: 4225112 [email protected] Websites www.worldbank.org.np, Website www.bishwabank.org.np www.dfid.gov.uk A copublication of The World Bank and the Department For International Development, U.K. -

Nationalism and Regional Relations in Democratic Transitions: Comparing Nepal and Bhutan

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2018 Nationalism and Regional Relations in Democratic Transitions: Comparing Nepal and Bhutan Deki Peldon Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Peldon, Deki, "Nationalism and Regional Relations in Democratic Transitions: Comparing Nepal and Bhutan" (2018). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1981. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1981 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONALISM AND REGIONAL RELATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS: COMPARING NEPAL AND BHUTAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By DEKI PELDON Bachelor of Arts, Asian University for Women, 2014 2018 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL [May 4, 2018] I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY DEKI PELDON ENTITLED NATIONALISM AND REGIONAL RELATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS: COMPARING NEPAL AND BHUTAN BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS. Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Thesis Director Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Director, Master of Arts Program in International and Comparative Politics Committee on Final Examination: Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs Pramod Kantha, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs Judson Murray, Ph.D. -

Indigenous Approaches to Knowledge Generation

INDIGENOUS APPROACHES TO KNOWLEDGE GENERATION Unveiling the Ways to Knowledge Generation, Continuation, Distribution and Control of the Pariyars: Commonalities and Points of Departure from School Pedagogy By Ganga Bahadur Gurung This thesis is submitted to the Tribhuvan University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Master of Philosophy in Education January, 2009 Abstract The purpose of the study was to uncover the approaches to knowledge generation, continuation, distribution and control of the Pariyars, one of the least privileged caste groups of Nepal. I even tried to explore the commonalities and points of departure between the Pariyars' indigenous knowledge and our school pedagogy. The principal research question of my study was: How do the Pariyars of Nepal generate the knowledge regarding music and what are the indigenous approaches they use in knowledge generation? To ease my study, I formulated three subsidiary questions focusing on knowledge distribution, control and the ways to knowledge generation at home and at school. The review of the literature covered the general review of different types of literature regarding the Panchai Baja followed by the review of specific theoretical closures regarding the knowledge generation of the Pariyars and the issues linked herewith. As my study area was basically focused on the perceptions of the individuals regarding the culture they live in, their ways of knowledge generation and other ideas associated to indigenous knowledge, I adopted the qualitative research methods. Since my study was more cultural and was more linked with the perceptions of the individuals, I used ethnographic methods to unveil the indigenous knowledge of the Pariyars. -

How Does Social Protection Contribute to Social Inclusion in Nepal?

February 2014 Report How does social protection contribute to social inclusion in Nepal? Evidence from the Child Grant in the Karnali Region Tej Prasad Adhikari1, Fatik Bahadur Thapa1, Sonam Tamrakar1, Prakash Buda Magar1, Jessica Hagen-Zanker2 and Babken Babajanian2 1NEPAN 2ODI This study uses a social exclusion lens to analyse the effects of Nepal’s Child Grant in Karnali region and tests assumptions about the role social protection can play in contributing to social inclusion and poverty reduction. The study used mixed methods and employed a quasi-experimental impact evaluation. The findings show that in the first three years of implementation, the Child Grant has had only small effects on some indicators of social inclusion, most notably access to a more diversified diet. The research suggests that the impact of the Child Grant is limited by both design and implementation bottlenecks. Shaping policy for development odi.org Preface This report is part of a wider research project that assessed the effectiveness and relevance of social protection and labour programmes in promoting social inclusion in South Asia. The research was undertaken in collaboration with partner organisations in four countries, examining BRAC’s life skills education and livelihoods trainings for young women in Afghanistan, the Chars Livelihoods Programme and the Vulnerable Group Development Programme in Bangladesh, India’s National Health Insurance Programme (RSBY) in Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh and the Child Grant in the Karnali region of Nepal. Reports and briefings for each country and a paper providing cross-country analysis and drawing out lessons of relevance for regional and international policy can be found at: www.odi.org/sp-inclusion. -

Nepali Times

#309 4 - 10 August 2006 16 pages Rs 30 Maoists are on a public relations offensive out west Weekly Internet Poll # 309 Q. How hopeful are you that the UN mission will be successful in overseeing arms management? Total votes: 3,359 Sword into ploughshare Weekly Internet Poll # 310. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com Q. Rate the performance of the seven party alliance government after 100 days in office. RAMESWOR BOHARA RAMESWOR BOHARA help us in the fields, so we are power comes from the people. “If Many still think the ceasefire in SURKHET not as afraid as we used to be.” the leaders decide to disband the is another Maoist ploy. But Just three months of ceasefire, PLA we will go along with it,” Comrade Ramesh appears contrite, s he readied his paddy and it is hard to to tell that these says Comrade Pratik of the rebel's “We will now turn from terrace for planting last lush green hills have been soaked Sixth Division. destruction to development.” z Aweek, Ram Bahadur Gurung with blood the past ten years. The of Gumi VDC in Surkhet got a Maoists murdered party workers, pleasant surprise. A group of teachers, traders. More died in armed Maoists volunteered to help brutal crackdowns by state Farewell to arms? him. security. The high-level UN mission lead by Staffan de Mistura returned to New Some comrades ploughed the The rebels cut suspension York Thursday without being able to persuade the Maoists and the field, others used the hoe and the bridges, blew up telecom towers, government to come up with a common position on demilitarising before women guerrillas waded knee-deep roads, radio transmitters, elections. -

Nepal Studies Association Bulletin, No. 10 Nepal Studies Association

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Nepal Studies Association Newsletter Yale Himalaya Initiative Spring 1976 Nepal Studies Association Bulletin, No. 10 Nepal Studies Association Donald A. Messerschmidt Washington State University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ yale_himalaya_initiative_nepal_studies Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Forest Management Commons, Geography Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Nepal Studies Association and Messerschmidt, Donald A., "Nepal Studies Association Bulletin, No. 10" (1976). Nepal Studies Association Newsletter. 10. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/yale_himalaya_initiative_nepal_studies/10 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by the Yale Himalaya Initiative at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nepal Studies Association Newsletter by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'NEPAL STUDIES ASSOCIATION BULLETIN SPRING 1976 THREE TIMES ANNUALLY NUMBER 10 TABLE OF CONTENTS IN THIS ISSUE - SPECIAL NOTE: INFORMATION FOR THE MEMBERS: p.2 Election for Executive Committee Please vote for the three Executive Membership Fees Due Committeemen (for terms 1976-1979) p.3 Treasurer's Report on the attached colored ballot form. Report from Kathmandu See page 2 for details. p.4 Report from Claremont Nepalese Students at SIU Please pay your membership dues SEMINARS AND MEETINGS: promptly. The future of this p.5 Humanities Seminar (in Nepal) Bulletin depends on them! See page Hill Lands Seminar (in USA) 2 and the Treasurer's Report, page 3. -

(EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli

FAMILY (EN) GROUP (EN) KEYWORD (EN) SYNONYMS, ALTERNATIVE TR Percussion Bells Abanangbweli Wind Accordions Accordion Strings Zithers Accord‐zither Percussion Drums Adufe Strings Musical bows Adungu Strings Zithers Aeolian harp Keyboard Organs Aeolian organ Wind Others Aerophone Percussion Bells Agogo Ogebe ; Ugebe Percussion Drums Agual Agwal Wind Trumpets Agwara Wind Oboes Alboka Albogon ; Albogue Wind Oboes Algaita Wind Flutes Algoja Algoza Wind Trumpets Alphorn Alpenhorn Wind Saxhorns Althorn Wind Saxhorns Alto bugle Wind Clarinets Alto clarinet Wind Oboes Alto crumhorn Wind Bassoons Alto dulcian Wind Bassoons Alto fagotto Wind Flugelhorns Alto flugelhorn Tenor horn Wind Flutes Alto flute Wind Saxhorns Alto horn Wind Bugles Alto keyed bugle Wind Ophicleides Alto ophicleide Wind Oboes Alto rothophone Wind Saxhorns Alto saxhorn Wind Saxophones Alto saxophone Wind Tubas Alto saxotromba Wind Oboes Alto shawm Wind Trombones Alto trombone Wind Trumpets Amakondere Percussion Bells Ambassa Wind Flutes Anata Tarca ; Tarka ; Taruma ; Turum Strings Lutes Angel lute Angelica Percussion Rattles Angklung Mechanical Mechanical Antiphonel Wind Saxhorns Antoniophone Percussion Metallophones / Steeldrums Anvil Percussion Rattles Anzona Percussion Bells Aporo Strings Zithers Appalchian dulcimer Strings Citterns Arch harp‐lute Strings Harps Arched harp Strings Citterns Archcittern Strings Lutes Archlute Strings Harps Ardin Wind Clarinets Arghul Argul ; Arghoul Strings Zithers Armandine Strings Zithers Arpanetta Strings Violoncellos Arpeggione Keyboard -

Caste Based Discrimination in Nepal” Has Been Taken out from Our Report on Caste Based Discrimination in South Asia

Caste-based Discrimination in Nepal Krishna B. Bhattachan Tej B. Sunar Yasso Kanti Bhattachan (Gauchan) Working Paper Series Indian Institute of Dalit Studies New Delhi Foreword Indian Institute of Dalit Studies (IIDS) has been amongst the first research organizations in India to focus exclusively on development concerns of the marginalized groups and socially excluded communities. Over the last six year, IIDS has carried-out several studies on different aspects of social exclusion and discrimination of the historically marginalized social groups, such as the Scheduled Caste, Schedule Tribes and Religious Minorities in India and other parts of the sub-continent. The Working Paper Series disseminates empirical findings of the ongoing research and conceptual development on issues pertaining to the forms and nature of social exclusion and discrimination. Some of our papers also critically examine inclusive policies for the marginalized social groups. This Working Paper “Caste Based Discrimination in Nepal” has been taken out from our report on Caste Based Discrimination in South Asia. Drawn from the country report of Nepal, the paper provides insights to a number of historical markers that have been responsible for re-structuring of the State including the practice of caste-based discrimination and untouchability against Dalits in Nepal. This study prominently draws attention to the diverse nature of Dalit population which has to a greater extent revealed the in-depth nature of regional, linguistic, religious, and cultural, gender and class-based discrimination and exclusion. It further provides a detailed study of Constitutional provisions and policies with prior focus on historical discourses and present situation simultaneously; complementing the role of civil society organisations. -

National Population and Housing Census 2011 (National Report)

Volume 01, NPHC 2011 National Population and Housing Census 2011 (National Report) Government of Nepal National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Kathmandu, Nepal November, 2012 Acknowledgement National Population and Housing Census 2011 (NPHC2011) marks hundred years in the history of population census in Nepal. Nepal has been conducting population censuses almost decennially and the census 2011 is the eleventh one. It is a great pleasure for the government of Nepal to successfully conduct the census amid political transition. The census 2011 has been historical event in many ways. It has successfully applied an ambitious questionnaire through which numerous demographic, social and economic information have been collected. Census workforce has been ever more inclusive with more than forty percent female interviewers, caste/ethnicities and backward classes being participated in the census process. Most financial resources and expertise used for the census were national. Nevertheless, important catalytic inputs were provided by UNFPA, UNWOMEN, UNDP, DANIDA, US Census Bureau etc. The census 2011 has once again proved that Nepal has capacity to undertake such a huge statistical operation with quality. The professional competency of the staff of the CBS has been remarkable. On this occasion, I would like to congratulate Central Bureau of Statistics and the CBS team led by Mr.Uttam Narayan Malla, Director General of the Bureau. On behalf of the Secretariat, I would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Population and Housing census 2011 headed by Honorable Vice-Chair of the National Planning commission. Also, thanks are due to the Members of various technical committees, working groups and consultants. -

Times in India, EKT Edition

This is a daily collection of all sorts of interesting stuff for you to read about during the trip. The guides can’t cover everything; so this is a way for me to fill in some of those empty spaces about many of the different aspects of this fascinating culture. THE Once Upon a TIMES OF INDIA PUBLISHED FOR EDDIE’S KOSHER TRAVEL GUESTS, WITH TONGUE IN CHEEK OCTOBER 2014 בן בג בג אומר: ”הפוך בה והפוך בה, דכולא בה“ )אבות ה‘( INDIA! - An Explorer’s Note Thanks to Eddie’s Kosher still dark. Thousands of peo- concept completely. Do not WELCOME Travel and you, I am coming ple were all over the place look upon India with western back to India now for the waiting for trains, I imagine, eyes, and do not judge it. If TO INDIA! 25th time; and every time I’m and sleeping on the station you do, you will diminish not quite sure what type of platforms. Here too, many both it and your experience. India I will find. Over the beggars are already at "work" Learn it. Feel it. Imbibe it. years that I have travelled coming up to me with hands Accept it. Wrap your head here regularly, I have grown outstretched. While I under- around it. Understand it for to love India, specially its stand the Indian worldview of what it is. For it is India. people, who seemed to have caste and karma, and why by an attitude of "there is always and large no one helps the When I was here for the first room for one more." I find poverty stricken, I find it time in 1999, India’s popula- the people in India to be pa- very, very disturbing.