Built on Sand an Examination of the Practice of Sand Mining in South Asia with Reflections from the Mahakali and the Teesta Rivers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments and Coping Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin”

MS “Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments Thesis and Coping Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin” “ Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments and Coping and Induced Critical Moments Flood and of Drought Identification Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin River Lower Teesta Prone Hazard Strategies in This thesis paper is submitted to the department of Geography & Environmental Studies, University of Rajshahi, as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MS - 2015. SUBMITTED BY Roll No. 10116087 Registration No. 2850 Session: 2014 - 15 MS Exam: 2015 ” April, 2017 Department of Geography and Sk. Junnun Sk. Al Third Science Building Environmental Studies, Faculty of Life and Earth Science - Hussain Rajshahi University Rajshahi - 6205 April, 2017 “Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments and Coping Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin” This thesis paper is submitted to the department of Geography & Environmental Studies, University of Rajshahi, as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science - 2015. SUBMITTED BY Roll No. 10116087 Registration No. 2850 Session: 2014 - 15 MS Exam: 2015 April, 2017 Department of Geography and Third Science Building Environmental Studies, Faculty of Life and Earth Science Rajshahi University Rajshahi - 6205 Dedicated To My Family i Declaration The author does hereby declare that the research entitled “Identification of Drought and Flood Induced Critical Moments and Coping Strategies in Hazard Prone Lower Teesta River Basin” submitted to the Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, University of Rajshahi for the Degree of Master of Science is exclusively his own, authentic and original study. -

“Sikkim Is Doing Very Well”

ON Tuesday, 05 April, 2005 Vol. 3 No. 291 Gangtok Rs. 3 05 April, 2005; NOW! 1 pg 2 SBI press CREDIT POPE SBI announces Xpress XCredit.XX Personal Loans for JOHN XXX PAUL II net monthly incomes of Rs. 2,500 onwards; 18-times the salary; at The Great 10.25% interest! contact PT Bhutia 9434357921, Unifier Chettri 94340 12824 or P Darnal 9434151288 “SIKKIM IS DOING VERY WELL” UNION HOME MINISTER RETURNS IMPRESSED WITH SIKKIM SUBASH RAI GANGTOK, 04 April: The Union Home Minister, Shivraj Patil, today expressed praise for the Army jawans posted in the frozen heights of Nathula at 14,000 ft. guarding the Indo- China border. “I feel relaxed by the thought that we have such brave and diligent soldiers keeping a watch for us,” he said while speaking to reporters at Nathula today. On the last day of his three- day visit to Sikkim, Mr. Patil, accompanied by his family and the Minister of State for Home, Manik Rao Ganit, was es- corted to the Indo-China bor- der Chief Minister Pawan Chamling and shown around by the GOC 17 Mountain Di- vision, Avadesh Prakash. Leaving early, the Union Home Minister’s entourage trav- elled by road to Nathula this morning. The entire stretch, from 3rd Mile onwards was swathed in fresh snow and reached The Union Home Minister, Shivraj Patil, takes a pony ride with his grand-daughter, from the road-head to Nathula pass on Monday Nathula at around 10 AM. While briefing the media working so efficiently here.” situation, he would deliver the issues like infrastructural devel- perience will certainly help in persons at Nathula, the Home On the opening of Indo- right information to the Prime opment,” he said. -

Micro Cottage and Small Entrepreneur Refinancing

l;4fy{ a}+s lnld6]8 != n3' 3/]n tyf ;fgf pBd shf{ s| g zfvf C0fLsf] gfd k||b]z s| g zfvf C0fLsf] gfd k||b]z . 1 Fikkal Sarita Pradhan 1 2101 JANAKPU CHAND TAILORS 2 2 Fikkal Navin Katuwal 1 2102 HETAUD RADHA SUPPLIERS Bagmati 3 Fikkal Rita Shrestha 1 2103 AAMCHO HIMAL FENCY KAPADA PASAL 1 4 Fikkal Pramesh Lamichhane 1 2104 SURKHET TIKA KHADYA TATHA KIRANAPASAL Karnali 5 RAJMARGA CHOWK KANKAI SUPPLIERS 1 2105 DHANGA KARUNA ELECTRONICS Sudurpashchim 6 Sindhuli unique electronic pasal 4 2106 DHANGA ANKIT NASTA PASAL Sudurpashchim 7 Sindhuli Kamal Bahadur khadka 5 2107 BUDIGAN TU FURNITURE UDHOG Sudurpashchim 8 Farsatikar New Kharel Order Suppliers 5 2108 BUDDHA SHUBHECHCHHA FANCY PASAL Gandaki 9 Taplejung Chandani Hotel 1 2109 TULSIPU NEW DANGI PLUMBINGSUPPLIERS 5 10 Taplejung Tej Bir Limbu 1 2110 HETAUD AMRITA KIRANA AND COLDSTORES Bagmati 11 Taplejung Dipak Gurung 1 2111 YASHOD SHUBHAM MOBILE CENTER 5 12 Taplejung Ganga Bahadur Limbu 1 2112 GADHI RAMU WORKSHOP 1 13 Taplejung Som Bimali 1 2113 DHANGA SANJAY AND YAMAN TRADERS Sudurpashchim 14 Taplejung Hari Kumar Limbu 1 2114 GOKULG G.N. ELECTRONICS AND MOBILECENTER Bagmati 15 Taplejung Chhowang Sherpa 1 2115 AAMCHO LOK BAHADUR KIRANA PASAL 1 16 Taplejung Gopal Neupane 1 2116 GHORAHI NEW SABINA HOTEL 5 17 Birauta Prashidddi Tours and Travels Pvt Ltd. Gandaki 2117 BUDIGAN NAUBIS GENERAL STORE Sudurpashchim 18 Chandragadi Sagarmatha Treders 1 2118 BIRATCH KANCHHA BAHUUDESHYAKRISHI FIRM 1 19 Chandragadi Hotel Grindland 1 2119 AAMCHO NANGANU NUYAHANG TRADERS 1 20 Chandragadi Bina books and Stationery 1 2120 AAMCHO SAKENWA PHALPHUL TA. -

Chapter II: River System and Drainage

Chapter II: River System and Drainage 2.11ntroduction The sub-Himalayan Jalpaiguri district is endowed with intricate river systems originating from the Sikkim, Darjeeling, Bhutan and Tibetan Himalayas draining across the Himalayas (figure 2.1 ). The piedmont zone is dissected by mountain streams of various sizes. The proportion of river length and catchment area between zone of erosion and deposition in various types differ considerably (Starkel, L & Sarkar, S, 2002). The river systems of sub Himalayan Jalpaiguri district have been genetically classified in following 7 types by Starkel et.al, in 2008. (i) Large transit river originated in high Himalaya. This group is represented by three rivers Tista. Torsa and Sankosh, with perennial discharge, feed both by rain and melt waters. Deep canyons in marginal part and mega-fans in the foreland indicate very high water discharge and high sediment load. Great alluvial fans and braided channels with frequent avulsions extend far up to the river Brahmaputra. (ii Rivers dissecting Lesser Hm1alaya. Only river .laldhaka under this group dwin·, catchment. Jeeply mctsed also in the Duars. \Vhere it is draining the active rismg blocks. As a result. its tan surface is developing farther dcnvnstream. Other nvers dissecting southern part of Lesser Himalaya with catchments between 50-l 00 km) are located in the belt of higher precipitation (Clish. CheL DaimL Chmnurchi. Ret!.. \. ;abur Basra. Jainti etc. land form targe allm1al lims. :\ggradations tollow upstream mto the hills and farther downstream braided channels change to the meandering ones. (iii) Seasonal or episodic rivers draining only frontal zone of the Himalaya with highly 2 dissected catchments with an area between 10-30 km . -

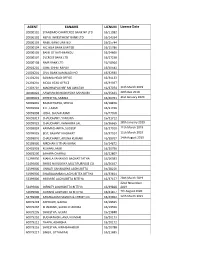

List of Active Agents

AGENT EANAME LICNUM License Date 20000101 STANDARD CHARTERED BANK NP LTD 16/11082 20000102 NEPAL INVESTMENT BANK LTD 16/14334 20000103 NABIL BANK LIMITED 16/15744 20000104 NIC ASIA BANK LIMITED 16/15786 20000105 BANK OF KATHMANDU 16/24666 20000107 EVEREST BANK LTD. 16/27238 20000108 NMB BANK LTD 16/18964 20901201 GIME CHHETRAPATI 16/30543 21001201 CIVIL BANK KAMALADI HO 16/32930 21101201 SANIMA HEAD OFFICE 16/34133 21201201 MEGA HEAD OFFICE 16/34037 21301201 MACHHAPUCHRE BALUWATAR 16/37074 11th March 2019 40000022 AAWHAN BAHUDAYSIYA SAHAKARI 16/35623 20th Dec 2019 40000023 SHRESTHA, SABINA 16/40761 31st January 2020 50099001 BAJRACHARYA, SHOVA 16/18876 50099003 K.C., LAXMI 16/21496 50099008 JOSHI, SHUVALAXMI 16/27058 50099017 CHAUDHARY, YAMUNA 16/31712 50099023 CHAUDHARY, KANHAIYA LAL 16/36665 28th January 2019 50099024 KARMACHARYA, SUDEEP 16/37010 11th March 2019 50099025 BIST, BASANTI KADAYAT 16/37014 11th March 2019 50099026 CHAUDHARY, ARUNA KUMARI 16/38767 14th August 2019 50199000 NIRDHAN UTTHAN BANK 16/14872 50401003 KISHAN LAMKI 16/20796 50601200 SAHARA CHARALI 16/22807 51299000 MAHILA SAHAYOGI BACHAT TATHA 16/26083 51499000 SHREE NAVODAYA MULTIPURPOSE CO 16/26497 51599000 UNNATI SAHAKARYA LAGHUBITTA 16/28216 51999000 SWABALAMBAN LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/33814 52399000 MIRMIRE LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/37157 28th March 2019 22nd November 52499000 INFINITY LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/39828 2019 52699000 GURANS LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA 16/41877 7th August 2020 52799000 KANAKLAXMI SAVING & CREDIT CO. 16/43902 12th March 2021 60079203 ADHIKARI, GAJRAJ -

Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal

UNEQUAL CITIZENS UNEQUAL37966 Public Disclosure Authorized CITIZENS Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal Caste and Ethnic Exclusion Gender, THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development SUMMARY BANK The World Bank DFID Nepal Nepal Office P.O. Box 106 P.O. Box 798 Kathmandu, Nepal Yak and Yeti Hotel Tel.: 5542980 Complex Fax: 5542979 Durbar Marg Public Disclosure Authorized Kathmandu, Nepal Tel.: 4226792, 4226793 E-mail Fax: 4225112 [email protected] Websites www.worldbank.org.np, Website www.bishwabank.org.np www.dfid.gov.uk Public Disclosure Authorized DFID Development International Department For ISBN 99946-890-0-2 9 799994 689001 > BANK WORLD THE Public Disclosure Authorized A Kathmandu businessman gets his shoes shined by a Sarki. The Sarkis belong to the leatherworker subcaste of Nepal’s Dalit or “low caste” community. Although caste distinctions and the age-old practices of “untouchability” are less rigid in urban areas, the deeply entrenched caste hierarchy still limits the life chances of the 13 percent of Nepal’s population who belong to the Dalit caste group. UNEQUAL CITIZENS Gender, Caste and Ethnic Exclusion in Nepal SUMMARY THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development BANK THE Department For International WORLD DFID Development BANK The World Bank DFID Nepal Nepal Office P.O. Box 106 P.O. Box 798 Kathmandu, Nepal Yak and Yeti Hotel Complex Tel.: 5542980 Durbar Marg Fax: 5542979 Kathmandu, Nepal Tel.: 4226792, 4226793 E-mail Fax: 4225112 [email protected] Websites www.worldbank.org.np, Website www.bishwabank.org.np www.dfid.gov.uk A copublication of The World Bank and the Department For International Development, U.K. -

District Survey Report of Kalimpong District

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT OF KALIMPONG DISTRICT (For mining of minor minerals) As per Notification No. S.O.3611 (E) New Delhi Dated 25th of July 2018 and Enforcement & Monitoring Guidelines for Sand Mining (EMGSM) January 2020, Issued by Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF & CC) Government of West Bengal (WORK ORDER No: MDTC/PM-5/160/66, dated 20.01.2020) July, 2021 CONSULTANT District Survey Report Kalimpong District, West Bengal Table of Content Chapter No Subject Page No 1 Preface 1-2 2 Introduction 3-15 3 General Profile of The District 16-36 a. General Information 16-17 b. Climate Condition 18 c. Rainfall and humidity 18-20 d. Topography & Terrain 20 e. Water courses and Hydrology 21-22 f. Ground water Development 23 g. Drainage System 23-25 h. Demography 25-27 i. Cropping pattern 27 j. Land Form and Seismicity 27-31 k. Flora 31-34 l. Fauna 34-36 4 Physiography of the District 37-41 4.1 General Landforms 37-38 4.2 Soil and rock pattern 38-40 4.3 Different geomorphology units 40-41 5 Land Use Pattern of The District 42-51 5.1 Forest 44-46 5.2 Agriculture and Irrigation 46-50 Work order No. MDTC/PM-5/160/66; dt. 20.1.2020 District Survey Report Kalimpong District, West Bengal 5.3 Horticulture 50-51 5.4 Mining 51 6 Geology 52-54 Regional and local geology with geological succession 52-54 7 Mineral Wealth 55-79 7.1 Overview of mineral resources 55 7.2 Details of Resources 55-77 7.2.1 Sand and other riverbed minerals 55-73 I. -

Nationalism and Regional Relations in Democratic Transitions: Comparing Nepal and Bhutan

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2018 Nationalism and Regional Relations in Democratic Transitions: Comparing Nepal and Bhutan Deki Peldon Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the International Relations Commons Repository Citation Peldon, Deki, "Nationalism and Regional Relations in Democratic Transitions: Comparing Nepal and Bhutan" (2018). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 1981. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/1981 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NATIONALISM AND REGIONAL RELATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS: COMPARING NEPAL AND BHUTAN A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By DEKI PELDON Bachelor of Arts, Asian University for Women, 2014 2018 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL [May 4, 2018] I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY DEKI PELDON ENTITLED NATIONALISM AND REGIONAL RELATIONS IN DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS: COMPARING NEPAL AND BHUTAN BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS. Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Thesis Director Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. Director, Master of Arts Program in International and Comparative Politics Committee on Final Examination: Laura M. Luehrmann, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs Pramod Kantha, Ph.D. School of Public and International Affairs Judson Murray, Ph.D. -

ENVIS Sikkim

ACTION PLAN FOR REJUVENATION OF FOUR IDENTIFIED POLLUTED RIVER STRETCHES OF SIKKIM SUBMITTED BY: RIVER REJUVENATION COMMITTEE -SIKKIM CONSTITUTED VIDE NOTIFICATION NO. GOS/FEWMD/PR.SEC-PCCF/161 DATED 23.01.2019 CONTENTS 1. Chapter 1 1 Introduction 2. Chapter 2 4 2.1 Identification of Polluted River Stretches 2.2. Criteria for priority five 4 3. Chapter 3 6 Components of Action Plan 4. Chapter 4 7 The Maney Khola (Adampool to Burtuk stretch) rejuvenation Action Plan. 5. Chapter 5 13 The Rangit Revjuvenation Plan (Dam site NHPC to Triveni Stretch). 6. Chapter 6 18 The Rani-Chu (Namli to Singtam Stretch) rejuvenation plan. 7. Chapter 7 25 The Teesta River (Melli to Chungthang Stretch) Rejuvenation Plan. LIST OF FIGURES 1. Map of Sikkim 2 2. Map showing the rivers of Sikkim 3 3. Map showing the river stretch between Adampool and Burtuk. 9 4. Map showing the river stretch between Rangit NHPC Dam site 14 and Triveni. 5. Map showing the river stretch between Namli and Singtam. 20 6. Map showing river stretch between Chungthang and Melli. 27 LIST OF TABLES 1. NWMP Stations 5 2. List of Hospitals in Gangtok 8 3. Action Plan for Maney Khola 10 4. List of water based industries along Rangit river 13 5. Action Plan for Rangit River 15 6. List of water based industries along Rani Chu 18 7. Action Plan for Rani Chu river 21 8. List of water based industries along Teesta river 25 9. Action Plan for Teesta River 28 River Rejuvenation Action Plan -Sikkim ACTION PLAN FOR REJUVENATION OF FOUR (04) IDENTIFIED POLLUTED RIVER STRETCHES OF SIKKIM CHAPTER 1 1. -

Tender Notice

GOVERNMENT OF SIKKIM OFFICE OF THE CONSERVATOR OF FOREST (TERRITORIAL) FORESTS, ENVIRONMENT& WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT DEORALI 737102, GANGTOK. TENDER NOTICE Sealed tenders are invited by the Forest Environment and Wildlife Management Department to grant license for temporary collection of loose boulders, sand and stone from the following sites during the year 2015-16 (1st July, 2015 to 31st December, 2016) i.e. for a period of 18 months. Interested parties may collect the tender forms from 11th June, 2015 to 25th June, 2015 in the concerned Divisional Forest Office (Territorial) and last date of submission of the form is 25th June, 2015 before 12:00 pm to the concerned Divisional Forest Officer (Territorial) in their respective district offices at Gangtok/Mangan/Namchi and Gyalshing. Tender shall opened at 01:00 pm on 26th June, 2015 by the Committee constituted for the purpose in the office of the DFO (Territorial) at Gangtok/Mangan/Namchi and Gyalshing, respectively. NORTH (17) Earnest Type of Money to Offset Sl. Range Location Area Unit Produce be Price for No. available deposited Tender by TDR 1 Lachen Chhuba Khola 5000 sq ft Sand/Stone 1,500 15,000 2 Lachen Zema Chhu(above bridge) 10000 sq ft Sand/Stone 3,000 30,000 3 Lachen Zema Chuu(below bridge) 24000 sq ft Sand/Stone 7,200 72,000 4 Mangan Sangkalang River bed 100000 sq ft Sand/Stone 30,000 300,000 5 Mangan Rangrang river bed 4000 sq ft Sand/Stone 1,200 12,000 6 Mangan Lower Tingchim 45000 sq ft Sand/Stone 13,500 135,000 7 Tsungthang Munsithang let bank(A) 5000 sq ft Sand/Stone -

How Does Social Protection Contribute to Social Inclusion in Nepal?

February 2014 Report How does social protection contribute to social inclusion in Nepal? Evidence from the Child Grant in the Karnali Region Tej Prasad Adhikari1, Fatik Bahadur Thapa1, Sonam Tamrakar1, Prakash Buda Magar1, Jessica Hagen-Zanker2 and Babken Babajanian2 1NEPAN 2ODI This study uses a social exclusion lens to analyse the effects of Nepal’s Child Grant in Karnali region and tests assumptions about the role social protection can play in contributing to social inclusion and poverty reduction. The study used mixed methods and employed a quasi-experimental impact evaluation. The findings show that in the first three years of implementation, the Child Grant has had only small effects on some indicators of social inclusion, most notably access to a more diversified diet. The research suggests that the impact of the Child Grant is limited by both design and implementation bottlenecks. Shaping policy for development odi.org Preface This report is part of a wider research project that assessed the effectiveness and relevance of social protection and labour programmes in promoting social inclusion in South Asia. The research was undertaken in collaboration with partner organisations in four countries, examining BRAC’s life skills education and livelihoods trainings for young women in Afghanistan, the Chars Livelihoods Programme and the Vulnerable Group Development Programme in Bangladesh, India’s National Health Insurance Programme (RSBY) in Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh and the Child Grant in the Karnali region of Nepal. Reports and briefings for each country and a paper providing cross-country analysis and drawing out lessons of relevance for regional and international policy can be found at: www.odi.org/sp-inclusion. -

Rivers of India

Downloaded From examtrix.com Compilation of Rivers www.onlyias.in Mahanadi RiverDownloaded From examtrix.com Source: Danadkarnya Left bank: Sheonath, Hasdo and Mand Right bank: Tel, Jonk, Ong Hirakund dam Olive Ridley Turtles: Gahirmatha beach, Orissa: Nesting turtles River flows through the states of Chhattisgarh and Odisha. River Ends in Bay of Bengal Mahanadi RiverDownloaded From examtrix.com Mahanadi RiverDownloaded From examtrix.com • The Mahanadi basin extends over states of Chhattisgarh and Odisha and comparatively smaller portions of Jharkhand, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, draining an area of 1.4 lakh Sq.km. • It is bounded by the Central India hills on the north, by the Eastern Ghats on the south and east and by the Maikala range on the west. • The Mahanadi (“Great River”) follows a total course of 560 miles (900 km). • It has its source in the northern foothills of Dandakaranya in Raipur District of Chhattisgarh at an elevation of 442 m. • The Mahanadi is one of the major rivers of the peninsular rivers, in water potential and flood producing capacity, it ranks second to the Godavari. Mahanadi RiverDownloaded From examtrix.com • Other small streams between the Mahanadi and the Rushikulya draining directly into the Chilka Lake also forms the part of the basin. • After receiving the Seonath River, it turns east and enters Odisha state. • At Sambalpur the Hirakud Dam (one of the largest dams in India) on the river has formed a man-made lake 35 miles (55 km) long. • It enters the Odisha plains near Cuttack and enters the Bay of Bengal at False Point by several channels.