Dimensions of the Shadow Economy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

The Development Record and the Effectiveness of Foreign Aid

The Development Record and The Effectiveness of Foreign Aid MICHAEL CROSSWELL Critics of foreign aid argue that little or no progress has been made in the developing world. The Heritage Foundation's initial survey of economic freedom claimed: "Not only has U.S. development aid been wasted, it has actually retarded economic development in the countries that receive it. Not one country receiving foreign aid has succeeded in developing sustained economic growth." A recent Cato Institute attack alleged that "few programs have consumed as many resources with as few positive results as foreign aid . the recipients of that largesse have, by and large, failed to grow economically and develop democratically." On the basis of these sorts of claims, congressional critics have attacked foreign aid complaining that "poor countries are still poor." Others might concede that economic growth has been achieved in parts of the developing world, but argue that the poor have not benefited, owing to increased inequality in income. Additionally, some critics claim that few countries have graduated from foreign aid, and dependence on U.S. and other foreign aid has been perpetuated. Some have argued that foreign aid has largely been "poured down ratholes," and is now an obsolete relic of the Cold War. (With this view of the role of foreign aid during the Cold War, why would one expect development progress?) Looking towards the future, these critics see only dim prospects for successful development, and therefore little or no role at all for foreign aid.1 Each of these arguments follows the same logical structure: recipients of foreign aid have failed to make development progress; therefore foreign aid has failed. -

Superman: the Shadow Masters Free Download

SUPERMAN: THE SHADOW MASTERS FREE DOWNLOAD Paul Kupperberg,Rick Burchett | 48 pages | 01 Feb 2014 | Capstone Press | 9781434227683 | English | Mankato, United States DC Comics: Superman William Kowalk rated it really liked it Apr 14, Issue ST. As he searches for clues, electrical transformers beneath the street suddenly explode! Aisha rated it liked it Nov 30, This website uses cookies so you can place orders and we can provide the most secure and effective website Superman: The Shadow Masters. Cosmic Bounty Hunter by Blake A. Nothing but Net by Jake Maddox. Add links. It's Acrata, a super heroine who can teleport through shadows. Books Capstone 4D Our Imprints. Preview — Superman by Paul Kupperberg. Availability: Backorder. View Print Catalog. Views Read Edit View history. Superman isn't convinced. Mimi marked it as to-read May 14, Superman and Acrata must stop him from casting an evil shadow over Earth. Ps too short but good. Artist Rick Burchett. Jinuka rated it really liked it Sep 29, This item is currently not available, but we will special Superman: The Shadow Masters a copy from our supplier if you choose to backorder it from us today. Clark quickly changes into his alter ego, Superman, Superman: The Shadow Masters locates the problem. If the Man of Steel isn't careful, it'll be Superman: The Shadow Masters out for him as well. Meteor of Doom by Paul Kupperberg. History Leadership Imprints. Olivia Hutchings added it Jul 08, Soon, he discovers an unexpected passenger aboard the spacecraft. The Deadly Dream Machine by J. Publisher Capstone Press. -

News from Sri Lanka

NEWS FROM www.adb.org/slrm Sri Lanka [email protected] ADB A Newsletter of the Sri Lanka Resident Mission of the July 2011 Asian Development Bank Message from New Country Director t is a privilege to write to you as the ADB I was Vice President, Risk new Country Director of the Sri Management with National Securities I Lanka Resident Mission. I would Clearing Corporation in New York and like to take this opportunity to prior to that, Manager and General introduce myself and also say a few Counsel at the Securities Exchanges words about ADB’s continuing support Guarantee Corporation Ltd - a to Sri Lanka. subsidiary of the Australian Stock As Country Director I will Exchange. I have also held positions oversee ADB’s public and private with the Australian Federal Attorney- sector operations in Sri Lanka. A General’s Office; the Papua New lawyer by profession with economic Guinea’s (PNG) State Solicitor’s qualifications, I have been working at Office; and in Australian and PNG law RITA O'SULLIVAN SLRM's new Country ADB for over 14 years, firstly as a firms. Director capital markets expert and later as legal As I transit fully to my new counsel, specializing in financial role, I take this opportunity to say that ensure that it is closely aligned with the sector development. For the last 10 ADB will continue to enhance its Government’s Development Policy years, I have also been responsible for longstanding development partnership Framework and ADB’s Strategy 2020. coordinating ADB’s anti-money with Sri Lanka as reflected in ADB’s I look forward to meeting the laundering/combating financing of country partnership strategy involving challenges to ensure positive and terrorism (AML/CFT) and related substantial levels of assistance in substantial developments during my trade security operations across the selected sectors. -

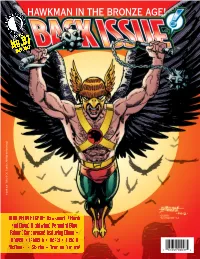

Hawkman in the Bronze Age!

HAWKMAN IN THE BRONZE AGE! July 2017 No.97 ™ $8.95 Hawkman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. BIRD PEOPLE ISSUE: Hawkworld! Hawk and Dove! Nightwing! Penguin! Blue Falcon! Condorman! featuring Dixon • Howell • Isabella • Kesel • Liefeld McDaniel • Starlin • Truman & more! 1 82658 00097 4 Volume 1, Number 97 July 2017 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST George Pérez (Commissioned illustration from the collection of Aric Shapiro.) COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Alter Ego Karl Kesel Jim Amash Rob Liefeld Mike Baron Tom Lyle Alan Brennert Andy Mangels Marc Buxton Scott McDaniel John Byrne Dan Mishkin BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury ............................2 Oswald Cobblepot Graham Nolan Greg Crosby Dennis O’Neil FLASHBACK: Hawkman in the Bronze Age ...............................3 DC Comics John Ostrander Joel Davidson George Pérez From guest-shots to a Shadow War, the Winged Wonder’s ’70s and ’80s appearances Teresa R. Davidson Todd Reis Chuck Dixon Bob Rozakis ONE-HIT WONDERS: DC Comics Presents #37: Hawkgirl’s First Solo Flight .......21 Justin Francoeur Brenda Rubin A gander at the Superman/Hawkgirl team-up by Jim Starlin and Roy Thomas (DCinthe80s.com) Bart Sears José Luís García-López Aric Shapiro Hawkman TM & © DC Comics. Joe Giella Steve Skeates PRO2PRO ROUNDTABLE: Exploring Hawkworld ...........................23 Mike Gold Anthony Snyder The post-Crisis version of Hawkman, with Timothy Truman, Mike Gold, John Ostrander, and Grand Comics Jim Starlin Graham Nolan Database Bryan D. Stroud Alan Grant Roy Thomas Robert Greenberger Steven Thompson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Penguin, Gotham’s Gentleman of Crime .......31 Mike Grell Titans Tower Numerous creators survey the history of the Man of a Thousand Umbrellas Greg Guler (titanstower.com) Jack C. -

What the Shadows Know 99

What the Shadows Know 99 What the Shadows Know: The Crime- Fighting Hero the Shadow and His Haunting of Late-1950s Literature Erik Mortenson During the Depression era of the 1930s and the war years of the 1940s, mil- lions of Americans sought escape from the tumultuous times in pulp magazines, comic books, and radio programs. In the face of mob violence, joblessness, war, and social upheaval, masked crusaders provided a much needed source of secu- rity where good triumphed over evil and wrongs were made right. Heroes such as Doc Savage, the Flash, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, Captain America, and Superman were always there to save the day, making the world seem fair and in order. This imaginative world not only was an escape from less cheery realities but also ended up providing nostalgic memories of childhood for many writers of the early Cold War years. But not all crime fighters presented such an optimistic outlook. The Shad- ow, who began life in a 1931 pulp magazine but eventually crossed over into radio, was an ambiguous sort of crime fighter. Called “the Shadow” because he moved undetected in these dark spaces, his name provided a hint to his divided character. Although he clearly defended the interests of the average citizen, the Shadow also satisfied the demand for a vigilante justice. His diabolical laughter is perhaps the best sign of his ambiguity. One assumes that it is directed at his adversaries, but its vengeful and spiteful nature strikes fear into victims, as well as victimizers. He was a tour guide to the underworld, providing his fans with a taste of the shady, clandestine lives of the criminals he pursued. -

Inter-Agency Real-Time Evaluation in Haiti: 3 Months After the Earthquake

Inter‐agency real‐time evaluation in Haiti: 3 months after the earthquake François Grünewald (Groupe URD) Andrea Binder (GPPi) With the support of Yvio Georges (National Consultant) August 31, 2010 FINAL REPORT 1 Map of Haiti and sites visited 2 Acknowledgements The evaluation team would like to thank all those who provided support and input during the research process and the field visit to Haiti. We are thankful to the representatives of the Haitian authorities who received us in Port‐au‐Prince, Lêogane, Jacmel and Gonaïves. We are also particularly grateful for the support of the OCHA office in Port‐au‐Prince who provided us with input and a work space and helped us organize the debriefing workshop. Thank you to CARE Haiti for hosting two of our workshops, the NGO Coordination Support Office in Haiti for helping us organize the workshop with international NGOs and the Haiti Response Coalition for organizing and hosting the workshop with Haitian NGOs. We would also like to thank Vincent Grammont for helping us travel to Bristout‐Bobin, Ravine Pintade and other areas in Port‐au‐Prince where access is difficult. Photos Camp Corail, Andrea Binder Destroyed settlements in Canapé Vert, François Grünewald 3 Acronyms ACF Action Contre la Faim ACAPS Assessment Capacities Project ALNAP Active Learning Network for Accountability and Performance CCCM Camp Coordination Camp Management CDAC Communication with Disaster Affected Communities CSC Coordination Support Committee DART Disaster Assessment and Relief Team DINEPA Direction Nationale de l'Eau -

British Community Development in Central Africa, 1945-55

School of History University of New South Wales Equivocal Empire: British Community Development in Central Africa, 1945-55 Daniel Kark A thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of New South Wales, Australia 2008 ORIGINALITY STATEMENT ‘I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and to the best of my knowledge it contains no materials previously published or written by another person, or substantial proportions of material which have been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma at UNSW or any other educational institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the thesis. Any contribution made to the research by others, with whom I have worked at UNSW or elsewhere, is explicitly acknowledged in the thesis. I also declare that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work, except to the extent that assistance from others in the project's design and conception or in style, presentation and linguistic expression is acknowledged.’ Signed …………………………………………….............. Date …………………………………………….............. For my parents, Vanessa and Adrian. For what you forfeited. Abstract This thesis resituates the Community Development programme as the key social intervention attempted by the British Colonial Office in Africa in the late 1940s and early 1950s. A preference for planning, growing confidence in metropolitan intervention, and the gradualist determination of Fabian socialist politicians and experts resulted in a programme that stressed modernity, progressive individualism, initiative, cooperative communities and a new type of responsible citizenship. Eventual self-rule would be well-served by this new contract between colonial administrations and African citizens. -

Excerpts from Hagakure (In the Shadow of Leaves)

Primary Source Document with Questions (DBQs) EXCERPTS FROM HAGAKURE (IN THE SHADOW OF LEAVES) Introduction Hagakure (In the Shadow of Leaves) has come to be known as a foundational text of bushidō, the “way of the warrior.” Dictated between 1709 and 1716 by a retired samurai, Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659-1719), to a young retainer, Tashirō Tsuramoto (1678-1748), Hagakure was less a rigorous philosophical exposition than the spirited reflections of a seasoned warrior. Although it became well known in the 1930s, when a young generation of nationalists embraced the supposed spirit of bushidō, Hagakure was not widely circulated in the Tokugawa period beyond Saga domain on the southern island of Kyushu, Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s home. Selected Document Excerpts with Questions From Sources of Japanese Tradition, edited by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Carol Gluck, and Arthur L. Tiedemann, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 476-478. © 2005 Columbia University Press. Reproduced with the permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. Excerpts from Hagakure (In the Shadow of Leaves) I have found that the Way of the samurai is death. This means that when you are compelled to choose between life and death, you must quickly choose death. There is nothing more to it than that. You just make up your mind and go forward. The idea that to die without accomplishing your purpose is undignified and meaningless, just dying like a dog, is the pretentious bushidō of the city slickers of Kyoto and Osaka. In a situation when you have to choose between life and death, there is no way to make sure that your purpose will be accomplished. -

Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics Kristen Coppess Race Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Race, Kristen Coppess, "Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics" (2013). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 793. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/793 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BATWOMAN AND CATWOMAN: TREATMENT OF WOMEN IN DC COMICS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By KRISTEN COPPESS RACE B.A., Wright State University, 2004 M.Ed., Xavier University, 2007 2013 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Date: June 4, 2013 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Kristen Coppess Race ENTITLED Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics . BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. Thesis Director _____________________________ Carol Loranger, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English Language and Literature Committee on Final Examination _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. _____________________________ Carol Mejia-LaPerle, Ph.D. _____________________________ Crystal Lake, Ph.D. _____________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. -

The Shadow Economy and Work in the Shadow: What Do We (Not) Know?

IZA DP No. 6423 The Shadow Economy and Work in the Shadow: What Do We (Not) Know? Friedrich Schneider March 2012 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor The Shadow Economy and Work in the Shadow: What Do We (Not) Know? Friedrich Schneider Johannes Kepler University of Linz and IZA Discussion Paper No. 6423 March 2012 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. IZA Discussion Paper No. -

Women in Clean Energy

WOMEN IN CLEAN ENERGY KNOWLEDGE, GAPS & OPPORTUNITIES Technology Collaboration Programme on Clean Energy, Education and Empowerment IEA MINISTERIAL MEETING SIDE EVENT, 7 November 2017 2 THE C3E TCP GOALS women in clean energy The Clean Energy, Education and Empowerment (C3E) Programme was created in 2010 as an initiative of the Clean Energy Ministerial (CEM) to enhance international collaboration and promote the leadership and participation of women in the clean energy transformation. In 2017, a decision was taken to organise the C3E’s activities as an IEA Technology Collaboration Programme (TCP). This provides a strong foundation to the work and provides additional visibility to the C3E TCP’s work globally. As a TCP, C3E joins a network of 6 000 experts participating in the Energy Technology Network (ETN), which engages in energy research and development, and can assist with the development of best practice sharing to support the goals of C3E. The 38 TCPs operating today involve nearly 300 public and private organisations in 53 countries. The C3E TCP has four areas of focus: Data collection Awards programmes Career development Dialogue The C3E TCP will enable stakeholders from around the globe to gather scientific knowledge, share ideas, host events, and exchange views on how to increase knowledge about women in clean energy and implement concrete actions to improve diversity in the energy sector. It was formally established as a TCP in June by founding members Canada, Italy and Sweden. Several additional countries are in the process of joining C3E. The C3E TCP offers broad visibility and leverages the high-level political engagement of energy ministers.