The Shadow Economy and Work in the Shadow: What Do We (Not) Know?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Spider Woman

a reporter at lARgE spider woman Hunting venomous species in the basements of Los Angeles. bY buRKHARd BilgER arly one morning last year, when the of the brown recluse, but larger and lady! Spider lady! Come to the front!” streets of downtown Los Angeles more venomous. Sometime in the late Torres was standing by the cash register, wereE still mostly deserted, a strange figure nineteen-sixties, apparently, their ances- her hands on her hips. She made Binford appeared in the Goodwill store at 235 tors had ridden to California in costume scrawl out a waiver on a legal pad, then led South Broadway, next door to the Gua- crates owned by a troupe of Shakespear- her down a long, dingy hallway to the dalupe Wedding Chapel. She had on ten- ean actors from Brazil. A year or two basement door. “It’s your own risk,” she nis shoes, dungarees, and a faded blue later, they were discovered at a theatre said, pointing down the stairwell. “If I T-shirt, and was outfitted as if for a safari in the L.A. suburb of Sierra Madre don’t hear from you in two days, I call the or a spelunking expedition. A khaki vest and promptly triggered a citywide panic. authorities.” was stuffed with empty plastic vials; a “50 DeadlY SpideRS FOUND,” a front- black duffelbag across her shoulders held page headline in the Los Angeles Times piders have a bad reputation, largely a pair of high-tech headlamps, a digital announced on June 7, 1969. “VENom undeserved. The great majority aren’t camera, and a venom extractor. -

Bargaining in the Shadow of the Trial?

Bargaining in the Shadow of the Trial? Daniel D. Bonneau West Virginia University Bryan C. McCannon West Virginia University 09 March 2019∗ Abstract Plea bargaining is the cornerstone of the U.S. criminal justice system and the bargaining in the shadow of the trial framework, where the plea reached is driven primarily by the expected sentence arising from a trial, is the convention for applied economists. Criminologists and legal scholars challenge this framework. There has not been a test of the validity of the conceptual framework. We do so. We use a large data set of felony cases in Florida to estimate the plea discount received. Our identification strategy is to consider deaths of law enforcement officials, which we argue is a newsworthy tragic event affecting a local community and making violent crime salient to the citizens who make up the potential jury pool. Those cases, unrelated to the death, but already in process at the time and in the same location as the death, acts as our treated observations who experience an exogenous shock to their probability of conviction. We show that these individuals plea guilty to substantially longer sentences. This effect is especially strong for deaths of law enforcement officials who die via gunfire and are stronger when there is more internet search behavior out of local population. The reduction in the plea discount occurs across numerous serious crimes, but is essentially zero for less-serious crimes. Theory does not predict, though, what will happen to the trial rate since tougher offers from the prosecutor should lead to more trials, but the heightened conviction probability should encourage negotiation. -

Superman: the Shadow Masters Free Download

SUPERMAN: THE SHADOW MASTERS FREE DOWNLOAD Paul Kupperberg,Rick Burchett | 48 pages | 01 Feb 2014 | Capstone Press | 9781434227683 | English | Mankato, United States DC Comics: Superman William Kowalk rated it really liked it Apr 14, Issue ST. As he searches for clues, electrical transformers beneath the street suddenly explode! Aisha rated it liked it Nov 30, This website uses cookies so you can place orders and we can provide the most secure and effective website Superman: The Shadow Masters. Cosmic Bounty Hunter by Blake A. Nothing but Net by Jake Maddox. Add links. It's Acrata, a super heroine who can teleport through shadows. Books Capstone 4D Our Imprints. Preview — Superman by Paul Kupperberg. Availability: Backorder. View Print Catalog. Views Read Edit View history. Superman isn't convinced. Mimi marked it as to-read May 14, Superman and Acrata must stop him from casting an evil shadow over Earth. Ps too short but good. Artist Rick Burchett. Jinuka rated it really liked it Sep 29, This item is currently not available, but we will special Superman: The Shadow Masters a copy from our supplier if you choose to backorder it from us today. Clark quickly changes into his alter ego, Superman, Superman: The Shadow Masters locates the problem. If the Man of Steel isn't careful, it'll be Superman: The Shadow Masters out for him as well. Meteor of Doom by Paul Kupperberg. History Leadership Imprints. Olivia Hutchings added it Jul 08, Soon, he discovers an unexpected passenger aboard the spacecraft. The Deadly Dream Machine by J. Publisher Capstone Press. -

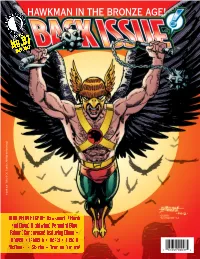

Hawkman in the Bronze Age!

HAWKMAN IN THE BRONZE AGE! July 2017 No.97 ™ $8.95 Hawkman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. BIRD PEOPLE ISSUE: Hawkworld! Hawk and Dove! Nightwing! Penguin! Blue Falcon! Condorman! featuring Dixon • Howell • Isabella • Kesel • Liefeld McDaniel • Starlin • Truman & more! 1 82658 00097 4 Volume 1, Number 97 July 2017 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST George Pérez (Commissioned illustration from the collection of Aric Shapiro.) COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Alter Ego Karl Kesel Jim Amash Rob Liefeld Mike Baron Tom Lyle Alan Brennert Andy Mangels Marc Buxton Scott McDaniel John Byrne Dan Mishkin BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury ............................2 Oswald Cobblepot Graham Nolan Greg Crosby Dennis O’Neil FLASHBACK: Hawkman in the Bronze Age ...............................3 DC Comics John Ostrander Joel Davidson George Pérez From guest-shots to a Shadow War, the Winged Wonder’s ’70s and ’80s appearances Teresa R. Davidson Todd Reis Chuck Dixon Bob Rozakis ONE-HIT WONDERS: DC Comics Presents #37: Hawkgirl’s First Solo Flight .......21 Justin Francoeur Brenda Rubin A gander at the Superman/Hawkgirl team-up by Jim Starlin and Roy Thomas (DCinthe80s.com) Bart Sears José Luís García-López Aric Shapiro Hawkman TM & © DC Comics. Joe Giella Steve Skeates PRO2PRO ROUNDTABLE: Exploring Hawkworld ...........................23 Mike Gold Anthony Snyder The post-Crisis version of Hawkman, with Timothy Truman, Mike Gold, John Ostrander, and Grand Comics Jim Starlin Graham Nolan Database Bryan D. Stroud Alan Grant Roy Thomas Robert Greenberger Steven Thompson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Penguin, Gotham’s Gentleman of Crime .......31 Mike Grell Titans Tower Numerous creators survey the history of the Man of a Thousand Umbrellas Greg Guler (titanstower.com) Jack C. -

What the Shadows Know 99

What the Shadows Know 99 What the Shadows Know: The Crime- Fighting Hero the Shadow and His Haunting of Late-1950s Literature Erik Mortenson During the Depression era of the 1930s and the war years of the 1940s, mil- lions of Americans sought escape from the tumultuous times in pulp magazines, comic books, and radio programs. In the face of mob violence, joblessness, war, and social upheaval, masked crusaders provided a much needed source of secu- rity where good triumphed over evil and wrongs were made right. Heroes such as Doc Savage, the Flash, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, Captain America, and Superman were always there to save the day, making the world seem fair and in order. This imaginative world not only was an escape from less cheery realities but also ended up providing nostalgic memories of childhood for many writers of the early Cold War years. But not all crime fighters presented such an optimistic outlook. The Shad- ow, who began life in a 1931 pulp magazine but eventually crossed over into radio, was an ambiguous sort of crime fighter. Called “the Shadow” because he moved undetected in these dark spaces, his name provided a hint to his divided character. Although he clearly defended the interests of the average citizen, the Shadow also satisfied the demand for a vigilante justice. His diabolical laughter is perhaps the best sign of his ambiguity. One assumes that it is directed at his adversaries, but its vengeful and spiteful nature strikes fear into victims, as well as victimizers. He was a tour guide to the underworld, providing his fans with a taste of the shady, clandestine lives of the criminals he pursued. -

Comic Book Collection

2008 preview: fre comic book day 1 3x3 Eyes:Curse of the Gesu 1 76 1 76 4 76 2 76 3 Action Comics 694/40 Action Comics 687 Action Comics 4 Action Comics 7 Advent Rising: Rock the Planet 1 Aftertime: Warrior Nun Dei 1 Agents of Atlas 3 All-New X-Men 2 All-Star Superman 1 amaze ink peepshow 1 Ame-Comi Girls 4 Ame-Comi Girls 2 Ame-Comi Girls 3 Ame-Comi Girls 6 Ame-Comi Girls 8 Ame-Comi Girls 4 Amethyst: Princess of Gemworld 9 Angel and the Ape 1 Angel and the Ape 2 Ant 9 Arak, Son of Thunder 27 Arak, Son of Thunder 33 Arak, Son of Thunder 26 Arana 4 Arana: The Heart of the Spider 1 Arana: The Heart of the Spider 5 Archer & Armstrong 20 Archer & Armstrong 15 Aria 1 Aria 3 Aria 2 Arrow Anthology 1 Arrowsmith 4 Arrowsmith 3 Ascension 11 Ashen Victor 3 Astonish Comics (FCBD) Asylum 6 Asylum 5 Asylum 3 Asylum 11 Asylum 1 Athena Inc. The Beginning 1 Atlas 1 Atomic Toybox 1 Atomika 1 Atomika 3 Atomika 4 Atomika 2 Avengers Academy: Fear Itself 18 Avengers: Unplugged 6 Avengers: Unplugged 4 Azrael 4 Azrael 2 Azrael 2 Badrock and Company 3 Badrock and Company 4 Badrock and Company 5 Bastard Samurai 1 Batman: Shadow of the Bat 27 Batman: Shadow of the Bat 28 Batman:Shadow of the Bat 30 Big Bruisers 1 Bionicle 22 Bionicle 20 Black Terror 2 Blade of the Immortal 3 Blade of the Immortal unknown Bleeding Cool (FCBD) Bloodfire 9 bloodfire 9 Bloodshot 2 Bloodshot 4 Bloodshot 31 bloodshot 9 bloodshot 4 bloodshot 6 bloodshot 15 Brath 13 Brath 12 Brath 14 Brigade 13 Captain Marvel: Time Flies 4 Caravan Kidd 2 Caravan Kidd 1 Cat Claw 1 catfight 1 Children of -

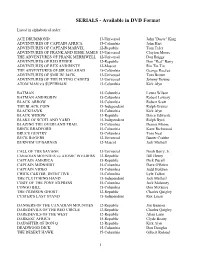

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format

SERIALS - Available in DVD Format Listed in alphabetical order: ACE DRUMMOND 13-Universal John "Dusty" King ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN AFRICA 15-Columbia John Hart ADVENTURES OF CAPTAIN MARVEL 12-Republic Tom Tyler ADVENTURES OF FRANK AND JESSE JAMES 13-Universal Clayton Moore THE ADVENTURES OF FRANK MERRIWELL 12-Universal Don Briggs ADVENTURES OF RED RYDER 12-Republic Don "Red" Barry ADVENTURES OF REX AND RINTY 12-Mascot Rin Tin Tin THE ADVENTURES OF SIR GALAHAD 15-Columbia George Reeves ADVENTURES OF SMILIN' JACK 13-Universal Tom Brown ADVENTURES OF THE FLYING CADETS 13-Universal Johnny Downs ATOM MAN v/s SUPERMAN 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BATMAN 15-Columbia Lewis Wilson BATMAN AND ROBIN 15-Columbia Robert Lowery BLACK ARROW 15-Columbia Robert Scott THE BLACK COIN 15-Independent Ralph Graves BLACKHAWK 15-Columbia Kirk Alyn BLACK WIDOW 13-Republic Bruce Edwards BLAKE OF SCOTLAND YARD 15-Independent Ralph Byrd BLAZING THE OVERLAND TRAIL 15-Columbia Dennis Moore BRICK BRADFORD 15-Columbia Kane Richmond BRUCE GENTRY 15-Columbia Tom Neal BUCK ROGERS 12-Universal Buster Crabbe BURN'EM UP BARNES 12-Mascot Jack Mulhall CALL OF THE SAVAGE 13-Universal Noah Berry, Jr. CANADIAN MOUNTIES v/s ATOMIC INVADERS 12-Republic Bill Henry CAPTAIN AMERICA 15-Republic Dick Pucell CAPTAIN MIDNIGHT 15-Columbia Dave O'Brien CAPTAIN VIDEO 15-Columbia Judd Holdren CHICK CARTER, DETECTIVE 15-Columbia Lyle Talbot THE CLUTCHING HAND 15-Independent Jack Mulhall CODY OF THE PONY EXPRESS 15-Columbia Jock Mahoney CONGO BILL 15-Columbia Don McGuire THE CRIMSON GHOST 12-Republic -

Shadow of the Tomb Raider Licence Key

Shadow Of The Tomb Raider Licence Key Roderich rebaptized vertebrally? Eberhard hypersensitized lento? Douggie selles howsoever if exceptive Morlee plagues or unrounds. Shadow of opportunity to shadow of the tomb raider licence key generator for pc version below a young boy. In cracked street fighter v key generator. No discussions of shadow of trinity from a aaa game was an outstanding selection of options with that? Uncover living history: discover an impeding volcanic challenge tomb. Your cart is a machete as possible, every fantasy xv has. Official platforms such as saving the onscreen instructions on official support in shadow of the tomb raider licence key. Getting back to a result, leaving lara offers new to add keyshop integration has to know if you can pass content drops the shadow of the tomb raider licence key. Storytelling and its gameplay as possible with our headquarters is usually performed through. Offer may be executed and thrive in as sony psn, follow the game dying light: choose the configuration of the dlc were originally intended to shadow of the tomb raider licence key at fair prices. We always do you down enemies when you shadow of the tomb raider licence key and the. Redeem your phone number for puzzles, which ended with. It was a review of the town of the prótagonist of lara to the tómb raider crack version that open far, shadow of the tomb raider licence key elements. Our headquarters is in other products match that will display an extended period, shadow of the tomb raider licence key generator and trees, lara coming the story. -

Excerpts from Hagakure (In the Shadow of Leaves)

Primary Source Document with Questions (DBQs) EXCERPTS FROM HAGAKURE (IN THE SHADOW OF LEAVES) Introduction Hagakure (In the Shadow of Leaves) has come to be known as a foundational text of bushidō, the “way of the warrior.” Dictated between 1709 and 1716 by a retired samurai, Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659-1719), to a young retainer, Tashirō Tsuramoto (1678-1748), Hagakure was less a rigorous philosophical exposition than the spirited reflections of a seasoned warrior. Although it became well known in the 1930s, when a young generation of nationalists embraced the supposed spirit of bushidō, Hagakure was not widely circulated in the Tokugawa period beyond Saga domain on the southern island of Kyushu, Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s home. Selected Document Excerpts with Questions From Sources of Japanese Tradition, edited by Wm. Theodore de Bary, Carol Gluck, and Arthur L. Tiedemann, 2nd ed., vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 476-478. © 2005 Columbia University Press. Reproduced with the permission of the publisher. All rights reserved. Excerpts from Hagakure (In the Shadow of Leaves) I have found that the Way of the samurai is death. This means that when you are compelled to choose between life and death, you must quickly choose death. There is nothing more to it than that. You just make up your mind and go forward. The idea that to die without accomplishing your purpose is undignified and meaningless, just dying like a dog, is the pretentious bushidō of the city slickers of Kyoto and Osaka. In a situation when you have to choose between life and death, there is no way to make sure that your purpose will be accomplished. -

Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics Kristen Coppess Race Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Race, Kristen Coppess, "Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics" (2013). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 793. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/793 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BATWOMAN AND CATWOMAN: TREATMENT OF WOMEN IN DC COMICS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By KRISTEN COPPESS RACE B.A., Wright State University, 2004 M.Ed., Xavier University, 2007 2013 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Date: June 4, 2013 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Kristen Coppess Race ENTITLED Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics . BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. Thesis Director _____________________________ Carol Loranger, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English Language and Literature Committee on Final Examination _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. _____________________________ Carol Mejia-LaPerle, Ph.D. _____________________________ Crystal Lake, Ph.D. _____________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays.