Excerpts from Hagakure (In the Shadow of Leaves)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Announces: the SHADOW Composed and Conducted By

Announces: THE SHADOW Composed and Conducted by JERRY GOLDSMITH Intrada Special Collection Volume ISC 204 Universal Pictures' 1994 The Shadow allowed composer Jerry Goldsmith to put his imprimatur on the darkly gothic phase of the superhero genre that developed in the 1990s. Writing for a large orchestra, Goldsmith created a score that found the perfect mix between heroism and menace and resulted in one of his longest scores. Goldsmith’s main title music introduces many of the score’s core elements: an unnerving pitch bend, played by synthesizers; a grandly powerful brass melody for the Shadow; and a bouncing electronic figure that will become a key rhythmic device throughout the score. Goldsmith’s classic sounding Shadow theme and the score’s large scale orchestrations complemented the film’s period setting and lavish look, while the composer’s trademark electronics helped better position the film for a contemporary audience. When the original soundtrack for The Shadow was released in 1994, it presented only a fraction of Jerry Goldsmith’s hour-and-twenty-minute score, reducing the composer’s wealth of action material to two cues and barely hinting at the complete score’s range and scope. In particular, Goldsmith’s elegant and haunting love theme—one of his best of the ’90s—plays only briefly at the very end of the album. This premiere presentation of the complete score represents one of the most substantial restorations of a Goldsmith soundtrack, illuminated by the fact that just 30 minutes of the full 85-minute score appeared on the original 1994 soundtrack album. -

1 Living Beside the Shadow of Death by Grace Lukach It's Hard to Say

1 Living Beside The Shadow of Death By Grace Lukach It’s hard to say when my Grandpa really began to die. Complications from an elective back surgery in 2001 forced him to spend two hundred non-consecutive days of the next year institutionalized—either in the hospital, nursing home, or in-house rehabilitation center. On three separate occasions he was put on a ventilator and for nearly nineteen of those two hundred days he relied on this machine to live. It seemed as though he were dying, but somehow, after all those months of suffering, he recovered his strength and returned home. He had escaped the clutches of death. And though he never again walked independently and would dream of physical activities as simple as driving, he was able to share monthly meals with old co-workers, attend weekly mass, and watch his children—and their children—grow up for six more years. Because of modern medicine, my Grandpa experienced six more years of being alive. But then my Grandpa fell and broke his hip. Back in the hospital, he was intubated and extubated and intubated again. A permanent pacemaker was implanted as well as a dialysis port, a tracheotomy, and a feeding tube. He was on and off the ventilator. Death was the enemy and everyone was fighting with every bit of energy they could muster, but nothing could keep him alive this time. After four months in the hospital, my Grandpa finally died. My Grandma’s journey to death is much clearer. She was a fighter who had regained full mobility after suffering a debilitating stroke that paralyzed her right side at the age of fifty-four. -

GAME DEVELOPERS a One-Of-A-Kind Game Concept, an Instantly Recognizable Character, a Clever Phrase— These Are All a Game Developer’S Most Valuable Assets

HOLLYWOOD >> REVIEWS ALIAS MAYA 6 * RTZEN RT/SHADER ISSUE AUGUST 2004 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>SIGGRAPH 2004 >>DEVELOPER DEFENSE >>FAST RADIOSITY SNEAK PEEK: LEGAL TOOLS TO SPEEDING UP LIGHTMAPS DISCREET 3DS MAX 7 PROTECT YOUR I.P. WITH PIXEL SHADERS POSTMORTEM: THE CINEMATIC EFFECT OF ZOMBIE STUDIOS’ SHADOW OPS: RED MERCURY []CONTENTS AUGUST 2004 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 7 FEATURES 14 COPYRIGHT: THE BIG GUN FOR GAME DEVELOPERS A one-of-a-kind game concept, an instantly recognizable character, a clever phrase— these are all a game developer’s most valuable assets. To protect such intangible properties from pirates, you’ll need to bring out the big gun—copyright. Here’s some free advice from a lawyer. By S. Gregory Boyd 20 FAST RADIOSITY: USING PIXEL SHADERS 14 With the latest advances in hardware, GPU, 34 and graphics technology, it’s time to take another look at lightmapping, the divine art of illuminating a digital environment. By Brian Ramage 20 POSTMORTEM 30 FROM BUNGIE TO WIDELOAD, SEROPIAN’S BEAT GOES ON 34 THE CINEMATIC EFFECT OF ZOMBIE STUDIOS’ A decade ago, Alexander Seropian founded a SHADOW OPS: RED MERCURY one-man company called Bungie, the studio that would eventually give us MYTH, ONI, and How do you give a player that vicarious presence in an imaginary HALO. Now, after his departure from Bungie, environment—that “you-are-there” feeling that a good movie often gives? he’s trying to repeat history by starting a new Zombie’s answer was to adopt many of the standard movie production studio: Wideload Games. -

Superman: the Shadow Masters Free Download

SUPERMAN: THE SHADOW MASTERS FREE DOWNLOAD Paul Kupperberg,Rick Burchett | 48 pages | 01 Feb 2014 | Capstone Press | 9781434227683 | English | Mankato, United States DC Comics: Superman William Kowalk rated it really liked it Apr 14, Issue ST. As he searches for clues, electrical transformers beneath the street suddenly explode! Aisha rated it liked it Nov 30, This website uses cookies so you can place orders and we can provide the most secure and effective website Superman: The Shadow Masters. Cosmic Bounty Hunter by Blake A. Nothing but Net by Jake Maddox. Add links. It's Acrata, a super heroine who can teleport through shadows. Books Capstone 4D Our Imprints. Preview — Superman by Paul Kupperberg. Availability: Backorder. View Print Catalog. Views Read Edit View history. Superman isn't convinced. Mimi marked it as to-read May 14, Superman and Acrata must stop him from casting an evil shadow over Earth. Ps too short but good. Artist Rick Burchett. Jinuka rated it really liked it Sep 29, This item is currently not available, but we will special Superman: The Shadow Masters a copy from our supplier if you choose to backorder it from us today. Clark quickly changes into his alter ego, Superman, Superman: The Shadow Masters locates the problem. If the Man of Steel isn't careful, it'll be Superman: The Shadow Masters out for him as well. Meteor of Doom by Paul Kupperberg. History Leadership Imprints. Olivia Hutchings added it Jul 08, Soon, he discovers an unexpected passenger aboard the spacecraft. The Deadly Dream Machine by J. Publisher Capstone Press. -

Hawkman in the Bronze Age!

HAWKMAN IN THE BRONZE AGE! July 2017 No.97 ™ $8.95 Hawkman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. BIRD PEOPLE ISSUE: Hawkworld! Hawk and Dove! Nightwing! Penguin! Blue Falcon! Condorman! featuring Dixon • Howell • Isabella • Kesel • Liefeld McDaniel • Starlin • Truman & more! 1 82658 00097 4 Volume 1, Number 97 July 2017 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER John Morrow Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST George Pérez (Commissioned illustration from the collection of Aric Shapiro.) COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Alter Ego Karl Kesel Jim Amash Rob Liefeld Mike Baron Tom Lyle Alan Brennert Andy Mangels Marc Buxton Scott McDaniel John Byrne Dan Mishkin BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury ............................2 Oswald Cobblepot Graham Nolan Greg Crosby Dennis O’Neil FLASHBACK: Hawkman in the Bronze Age ...............................3 DC Comics John Ostrander Joel Davidson George Pérez From guest-shots to a Shadow War, the Winged Wonder’s ’70s and ’80s appearances Teresa R. Davidson Todd Reis Chuck Dixon Bob Rozakis ONE-HIT WONDERS: DC Comics Presents #37: Hawkgirl’s First Solo Flight .......21 Justin Francoeur Brenda Rubin A gander at the Superman/Hawkgirl team-up by Jim Starlin and Roy Thomas (DCinthe80s.com) Bart Sears José Luís García-López Aric Shapiro Hawkman TM & © DC Comics. Joe Giella Steve Skeates PRO2PRO ROUNDTABLE: Exploring Hawkworld ...........................23 Mike Gold Anthony Snyder The post-Crisis version of Hawkman, with Timothy Truman, Mike Gold, John Ostrander, and Grand Comics Jim Starlin Graham Nolan Database Bryan D. Stroud Alan Grant Roy Thomas Robert Greenberger Steven Thompson BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Penguin, Gotham’s Gentleman of Crime .......31 Mike Grell Titans Tower Numerous creators survey the history of the Man of a Thousand Umbrellas Greg Guler (titanstower.com) Jack C. -

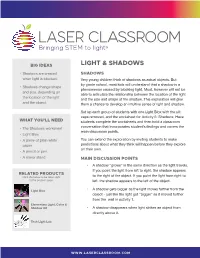

Light & Shadows

BIG IDEAS LIGHT & SHADOWS • Shadows are created SHADOWS when light is blocked. Very young children think of shadows as actual objects. But by grade school, most kids will understand that a shadow is a • Shadows change shape phenomenon caused by blocking light. Most, however will not be and size, depending on able to articulate the relationship between the location of the light the location of the light and the size and shape of the shadow. This exploration will give and the object. them a chance to develop an intuitive sense of light and shadow. Set up each group of students with one Light Blox with the slit caps removed, and the worksheet for Activity 5: Shadows. Have WHAT YOU’LL NEED students complete the worksheets and then hold a classroom conversation that incorporates student’s findings and covers the • The Shadows worksheet main discussion points. • Light Blox • A piece of plain white You can extend the exploration by inviting students to make paper predictions about what they think will happen before they explore on their own. • A pencil or pen • A mirror stand MAIN DISCUSSION POINTS • A shadow “grows” in the same direction as the light travels. If you point the light from left to right, the shadow appears RELATED PRODUCTS Click the below to be taken right to the right of the object. If you point the light from right to to the product page. left, the shadow appears to the left of the object. Light Blox • A shadow gets bigger as the light moves further from the object - just like the light got “bigger” as it moved further from the wall in activity 1. -

What the Shadows Know 99

What the Shadows Know 99 What the Shadows Know: The Crime- Fighting Hero the Shadow and His Haunting of Late-1950s Literature Erik Mortenson During the Depression era of the 1930s and the war years of the 1940s, mil- lions of Americans sought escape from the tumultuous times in pulp magazines, comic books, and radio programs. In the face of mob violence, joblessness, war, and social upheaval, masked crusaders provided a much needed source of secu- rity where good triumphed over evil and wrongs were made right. Heroes such as Doc Savage, the Flash, Wonder Woman, Green Lantern, Captain America, and Superman were always there to save the day, making the world seem fair and in order. This imaginative world not only was an escape from less cheery realities but also ended up providing nostalgic memories of childhood for many writers of the early Cold War years. But not all crime fighters presented such an optimistic outlook. The Shad- ow, who began life in a 1931 pulp magazine but eventually crossed over into radio, was an ambiguous sort of crime fighter. Called “the Shadow” because he moved undetected in these dark spaces, his name provided a hint to his divided character. Although he clearly defended the interests of the average citizen, the Shadow also satisfied the demand for a vigilante justice. His diabolical laughter is perhaps the best sign of his ambiguity. One assumes that it is directed at his adversaries, but its vengeful and spiteful nature strikes fear into victims, as well as victimizers. He was a tour guide to the underworld, providing his fans with a taste of the shady, clandestine lives of the criminals he pursued. -

The Invincible Shiwan Khan

THE INVINCIBLE SHIWAN KHAN Maxwell Grant THE INVINCIBLE SHIWAN KHAN Table of Contents THE INVINCIBLE SHIWAN KHAN..............................................................................................................1 Maxwell Grant.........................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. SPELL OF THE PAST.....................................................................................................1 CHAPTER II. DEATH'S CHOICE.........................................................................................................5 CHAPTER III. THE MASTER SPEAKS...............................................................................................9 CHAPTER IV. THREADS TO CRIME................................................................................................12 CHAPTER V. FROM SIX TO SEVEN................................................................................................16 CHAPTER VI. THE BRONZE KNIFE.................................................................................................21 CHAPTER VII. THE SECOND SUICIDE...........................................................................................24 CHAPTER VIII. QUEST OF MISSING MEN.....................................................................................27 CHAPTER IX. THE LONE TRAIL......................................................................................................31 CHAPTER X. PATH OF DARKNESS.................................................................................................35 -

The Shadow of an Invisible Cathedral

THE SHADOW OF AN INVISIBLE CATHEDRAL Change how a person conceives of space in his or her mind, I reflected, and you transform how they experience it in the world. I was in a state of near panic when the phone rang. Broke and unemployed, I was startled to recognize the voice of Berkeley’s architecture department director as she told me that a senior faculty member had died during the final days of summer and the school wanted me to teach her graduate seminar, Theories of Architectural Space. Frightened by the prospect of teaching a class for which I was grossly ill-prepared, yet desperate for work, I quickly reshaped the course in my mind into something I felt qualified to teach. “Sure I can do it,” I told the director after an awkward silence, “no problem.” My life at that point was falling apart. I had just completed my Ph.D. in architectural history and theory, and I was already weary of architecture as both a discipline and a means of employment. Unable to afford Berkeley rents, I had moved to a rundown Oakland apartment by a highway overpass. There weren’t any jobs, and I spent most of my days fantasizing an alternative life for myself as a successful novelist. Teaching was my only chance of supporting myself, so I used my love of fiction writing to jump-start my interest in architecture and molded the course into a seven-week graduate seminar I re-titled Spatial Narratives. Rather than presenting a survey of discursive touchstones on space, as the deceased professor had, I would have the students read short stories and excerpts from novels in which buildings figured prominently. -

PINBALL NVRAM GAME LIST This List Was Created to Make It Easier for Customers to Figure out What Type of NVRAM They Need for Each Machine

PINBALL NVRAM GAME LIST This list was created to make it easier for customers to figure out what type of NVRAM they need for each machine. Please consult the product pages at www.pinitech.com for each type of NVRAM for further information on difficulty of installation, any jumper changes necessary on your board(s), a diagram showing location of the RAM being replaced & more. *NOTE: This list is meant as quick reference only. On Williams WPC and Sega/Stern Whitestar games you should check the RAM currently in your machine since either a 6264 or 62256 may have been used from the factory. On Williams System 11 games you should check that the chip at U25 is 24-pin (6116). See additional diagrams & notes at http://www.pinitech.com/products/cat_memory.php for assistance in locating the RAM on your board(s). PLUG-AND-PLAY (NO SOLDERING) Games below already have an IC socket installed on the boards from the factory and are as easy as removing the old RAM and installing the NVRAM (then resetting scores/settings per the manual). • BALLY 6803 → 6116 NVRAM • SEGA/STERN WHITESTAR → 6264 OR 62256 NVRAM (check IC at U212, see website) • DATA EAST → 6264 NVRAM (except Laser War) • CLASSIC BALLY → 5101 NVRAM • CLASSIC STERN → 5101 NVRAM (later Stern MPU-200 games use MPU-200 NVRAM) • ZACCARIA GENERATION 1 → 5101 NVRAM **NOT** PLUG-AND-PLAY (SOLDERING REQUIRED) The games below did not have an IC socket installed on the boards. This means the existing RAM needs to be removed from the board & an IC socket installed. -

Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics Kristen Coppess Race Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Race, Kristen Coppess, "Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics" (2013). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 793. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/793 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BATWOMAN AND CATWOMAN: TREATMENT OF WOMEN IN DC COMICS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By KRISTEN COPPESS RACE B.A., Wright State University, 2004 M.Ed., Xavier University, 2007 2013 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Date: June 4, 2013 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Kristen Coppess Race ENTITLED Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics . BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. Thesis Director _____________________________ Carol Loranger, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English Language and Literature Committee on Final Examination _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. _____________________________ Carol Mejia-LaPerle, Ph.D. _____________________________ Crystal Lake, Ph.D. _____________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D.