What the Shadows Know 99

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Myth, Metatext, Continuity and Cataclysm in Dc Comics’ Crisis on Infinite Earths

WORLDS WILL LIVE, WORLDS WILL DIE: MYTH, METATEXT, CONTINUITY AND CATACLYSM IN DC COMICS’ CRISIS ON INFINITE EARTHS Adam C. Murdough A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2006 Committee: Angela Nelson, Advisor Marilyn Motz Jeremy Wallach ii ABSTRACT Angela Nelson, Advisor In 1985-86, DC Comics launched an extensive campaign to revamp and revise its most important superhero characters for a new era. In many cases, this involved streamlining, retouching, or completely overhauling the characters’ fictional back-stories, while similarly renovating the shared fictional context in which their adventures take place, “the DC Universe.” To accomplish this act of revisionist history, DC resorted to a text-based performative gesture, Crisis on Infinite Earths. This thesis analyzes the impact of this singular text and the phenomena it inspired on the comic-book industry and the DC Comics fan community. The first chapter explains the nature and importance of the convention of “continuity” (i.e., intertextual diegetic storytelling, unfolding progressively over time) in superhero comics, identifying superhero fans’ attachment to continuity as a source of reading pleasure and cultural expressivity as the key factor informing the creation of the Crisis on Infinite Earths text. The second chapter consists of an eschatological reading of the text itself, in which it is argued that Crisis on Infinite Earths combines self-reflexive metafiction with the ideologically inflected symbolic language of apocalypse myth to provide DC Comics fans with a textual "rite of transition," to win their acceptance for DC’s mid-1980s project of self- rehistoricization and renewal. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

Announces: the SHADOW Composed and Conducted By

Announces: THE SHADOW Composed and Conducted by JERRY GOLDSMITH Intrada Special Collection Volume ISC 204 Universal Pictures' 1994 The Shadow allowed composer Jerry Goldsmith to put his imprimatur on the darkly gothic phase of the superhero genre that developed in the 1990s. Writing for a large orchestra, Goldsmith created a score that found the perfect mix between heroism and menace and resulted in one of his longest scores. Goldsmith’s main title music introduces many of the score’s core elements: an unnerving pitch bend, played by synthesizers; a grandly powerful brass melody for the Shadow; and a bouncing electronic figure that will become a key rhythmic device throughout the score. Goldsmith’s classic sounding Shadow theme and the score’s large scale orchestrations complemented the film’s period setting and lavish look, while the composer’s trademark electronics helped better position the film for a contemporary audience. When the original soundtrack for The Shadow was released in 1994, it presented only a fraction of Jerry Goldsmith’s hour-and-twenty-minute score, reducing the composer’s wealth of action material to two cues and barely hinting at the complete score’s range and scope. In particular, Goldsmith’s elegant and haunting love theme—one of his best of the ’90s—plays only briefly at the very end of the album. This premiere presentation of the complete score represents one of the most substantial restorations of a Goldsmith soundtrack, illuminated by the fact that just 30 minutes of the full 85-minute score appeared on the original 1994 soundtrack album. -

Masculinism, Resistance, and Recognition in Vietnam

NORMA International Journal for Masculinity Studies ISSN: 1890-2138 (Print) 1890-2146 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rnor20 Recognising shadows: masculinism, resistance, and recognition in Vietnam Paul Horton To cite this article: Paul Horton (2019): Recognising shadows: masculinism, resistance, and recognition in Vietnam, NORMA, DOI: 10.1080/18902138.2019.1565166 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/18902138.2019.1565166 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group Published online: 11 Jan 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 110 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rnor20 NORMA: INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR MASCULINITY STUDIES https://doi.org/10.1080/18902138.2019.1565166 Recognising shadows: masculinism, resistance, and recognition in Vietnam Paul Horton Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, Linköping University, Linköping, Sweden ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Pride parades, LGBT rights demonstrations, and revisions to the Received 9 July 2017 Marriage and Family Law highlight the extent to which norms and Accepted 12 November 2018 values related to gender, sexuality, marriage, and the family have KEYWORDS recently been challenged in Vietnam. They also illuminate the Vietnam; LGBT; masculinism; gendered power relations being played out in the socio-cultural recognition; power; context of Vietnam, and thus open up for a more in-depth resistance consideration of the ways in which LGBT people have experienced and resisted these relations in everyday life. Drawing on ethnographic fieldwork conducted in Vietnam’s two largest cities, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, in 2012, this article discusses the relations between these power relations, the dominant Vietnamese discourse of masculinity, or masculinism, and the politics of recognition. -

Andy Warhol Shadows Exhibition Brochure.Pdf

Andy Warhol Shadows On Tuesday I hung my painting(s) at the Heiner Friedrich gallery in SoHo. Really it’s presentation. Since the number of panels shown varies according to the available and altered through the abstraction of the silkscreen stencil and the appli- one painting with 83 parts. Each part is 52 inches by 76 inches and they are all sort size of the exhibition space, as does the order of their arrangement, the work in cation of color to reconfigure context and meaning. The repetition of each of the same except for the colors. I called them “Shadows” because they are based total contracts, expands, and recalibrates with each installation. For the work’s famous face drains the image of individuality, so that each becomes a on a photo of a shadow in my office. It’s a silk screen that I mop over with paint. first display, the gallery accommodated 83 panels that were selected and arranged stand-in for non-individuated and depersonalized notions of celebrity.5 The I started working on them a few years ago. I work seven days a week. But I get by Warhol’s assistants in two rooms: the main gallery and an adjacent office. replication of a seemingly abstract gesture (a jagged peak and horizontal the most done on weekends because during the week people keep coming by extension) across the panels of Shadows further minimizes the potential to talk. The all-encompassing (if modular) scale of Shadows simultaneously recalls to ascribe any narrative logic to Warhol’s work. Rather, as he dryly explained, The painting(s) can’t be bought. -

Spider Woman

a reporter at lARgE spider woman Hunting venomous species in the basements of Los Angeles. bY buRKHARd BilgER arly one morning last year, when the of the brown recluse, but larger and lady! Spider lady! Come to the front!” streets of downtown Los Angeles more venomous. Sometime in the late Torres was standing by the cash register, wereE still mostly deserted, a strange figure nineteen-sixties, apparently, their ances- her hands on her hips. She made Binford appeared in the Goodwill store at 235 tors had ridden to California in costume scrawl out a waiver on a legal pad, then led South Broadway, next door to the Gua- crates owned by a troupe of Shakespear- her down a long, dingy hallway to the dalupe Wedding Chapel. She had on ten- ean actors from Brazil. A year or two basement door. “It’s your own risk,” she nis shoes, dungarees, and a faded blue later, they were discovered at a theatre said, pointing down the stairwell. “If I T-shirt, and was outfitted as if for a safari in the L.A. suburb of Sierra Madre don’t hear from you in two days, I call the or a spelunking expedition. A khaki vest and promptly triggered a citywide panic. authorities.” was stuffed with empty plastic vials; a “50 DeadlY SpideRS FOUND,” a front- black duffelbag across her shoulders held page headline in the Los Angeles Times piders have a bad reputation, largely a pair of high-tech headlamps, a digital announced on June 7, 1969. “VENom undeserved. The great majority aren’t camera, and a venom extractor. -

Bargaining in the Shadow of the Trial?

Bargaining in the Shadow of the Trial? Daniel D. Bonneau West Virginia University Bryan C. McCannon West Virginia University 09 March 2019∗ Abstract Plea bargaining is the cornerstone of the U.S. criminal justice system and the bargaining in the shadow of the trial framework, where the plea reached is driven primarily by the expected sentence arising from a trial, is the convention for applied economists. Criminologists and legal scholars challenge this framework. There has not been a test of the validity of the conceptual framework. We do so. We use a large data set of felony cases in Florida to estimate the plea discount received. Our identification strategy is to consider deaths of law enforcement officials, which we argue is a newsworthy tragic event affecting a local community and making violent crime salient to the citizens who make up the potential jury pool. Those cases, unrelated to the death, but already in process at the time and in the same location as the death, acts as our treated observations who experience an exogenous shock to their probability of conviction. We show that these individuals plea guilty to substantially longer sentences. This effect is especially strong for deaths of law enforcement officials who die via gunfire and are stronger when there is more internet search behavior out of local population. The reduction in the plea discount occurs across numerous serious crimes, but is essentially zero for less-serious crimes. Theory does not predict, though, what will happen to the trial rate since tougher offers from the prosecutor should lead to more trials, but the heightened conviction probability should encourage negotiation. -

NO RAMBLING ON: the LISTLESS COWBOYS of HORSE Jon Davies

WARHOL pages_BFI 25/06/2013 10:57 Page 108 If Andy Warhol’s queer cinema of the 1960s allowed for a flourishing of newly articulated sexual and gender possibilities, it also fostered a performative dichotomy: those who command the voice and those who do not. Many of his sound films stage a dynamic of stoicism and loquaciousness that produces a complex and compelling web of power and desire. The artist has summed the binary up succinctly: ‘Talk ers are doing something. Beaut ies are being something’ 1 and, as Viva explained about this tendency in reference to Warhol’s 1968 Lonesome Cowboys : ‘Men seem to have trouble doing these nonscript things. It’s a natural 5_ 10 2 for women and fags – they ramble on. But straight men can’t.’ The brilliant writer and progenitor of the Theatre of the Ridiculous Ronald Tavel’s first two films as scenarist for Warhol are paradigmatic in this regard: Screen Test #1 and Screen Test #2 (both 1965). In Screen Test #1 , the performer, Warhol’s then lover Philip Fagan, is completely closed off to Tavel’s attempts at spurring him to act out and to reveal himself. 3 According to Tavel, he was so up-tight. He just crawled into himself, and the more I asked him, the more up-tight he became and less was recorded on film, and, so, I got more personal about touchy things, which became the principle for me for the next six months. 4 When Tavel turned his self-described ‘sadism’ on a true cinematic superstar, however, in Screen Test #2 , the results were extraordinary. -

1 Living Beside the Shadow of Death by Grace Lukach It's Hard to Say

1 Living Beside The Shadow of Death By Grace Lukach It’s hard to say when my Grandpa really began to die. Complications from an elective back surgery in 2001 forced him to spend two hundred non-consecutive days of the next year institutionalized—either in the hospital, nursing home, or in-house rehabilitation center. On three separate occasions he was put on a ventilator and for nearly nineteen of those two hundred days he relied on this machine to live. It seemed as though he were dying, but somehow, after all those months of suffering, he recovered his strength and returned home. He had escaped the clutches of death. And though he never again walked independently and would dream of physical activities as simple as driving, he was able to share monthly meals with old co-workers, attend weekly mass, and watch his children—and their children—grow up for six more years. Because of modern medicine, my Grandpa experienced six more years of being alive. But then my Grandpa fell and broke his hip. Back in the hospital, he was intubated and extubated and intubated again. A permanent pacemaker was implanted as well as a dialysis port, a tracheotomy, and a feeding tube. He was on and off the ventilator. Death was the enemy and everyone was fighting with every bit of energy they could muster, but nothing could keep him alive this time. After four months in the hospital, my Grandpa finally died. My Grandma’s journey to death is much clearer. She was a fighter who had regained full mobility after suffering a debilitating stroke that paralyzed her right side at the age of fifty-four. -

Elementary Secondary Education Act Title This Seventh Grade Math

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 100 668 88 SE 018 359 PITTS Mathematics 7, Environmental Education Guide. INSTITUTION Project I-C-E, Green Bay, Wis. SPONS AGENCY Bureau of Elementary and Secondary Education (DHPW/OP), Washington, D.C.; Wisconsin State Dept. of Education, Madison. PUB DATE (74] NOT! 44p. EPRS PR/CE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Conservation Education; *Environmental Education; Grade 7; Instructional Materials; Interdisciplinary Approach; Learning Activities; *Mathematical Applications; Mathematics Education; Natural Resources; Outdoor Education; Science Education; Secondary Education; *Secondary School Mathematics; *Teaching Guides IDENTIFII2RS Computtion; Elementary Secondary Education Act Title III; ESEA Title III; *Project I C E; Proportion ABSTRACT This seventh grade mathematics guide ,s one of a series of guides, K-12, that were developed by teachers to help introduce environmental education into the total curriculum. The guides are supplementary in design, containing a series of episodes (minilessons) that reinforce the relationships between ecology and mathematics. It is the teacher's decision when the episodes may best be integrated into the existing classroom curriculum. The episodes are built around 12 major environmental concepts that form a framework for each grade or subject area, as well as for the entire K-12 program. Although the same concepts are used throughout the K-12 program, emphasis is placed on different aspects of each concept at different grade levels or subject levels. This guide focuses on aspects such as proportion, computation, and percent. The 12 concepts are covered in one of the episodes contained in the guide. Further, each episode offers subject area integration, subject area activities, interdisciplinary activities, cognitive and affective behavioral objectives, and suggested references and resource materials useful to teachers and students. -

GAME DEVELOPERS a One-Of-A-Kind Game Concept, an Instantly Recognizable Character, a Clever Phrase— These Are All a Game Developer’S Most Valuable Assets

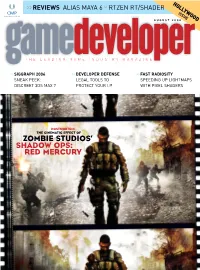

HOLLYWOOD >> REVIEWS ALIAS MAYA 6 * RTZEN RT/SHADER ISSUE AUGUST 2004 THE LEADING GAME INDUSTRY MAGAZINE >>SIGGRAPH 2004 >>DEVELOPER DEFENSE >>FAST RADIOSITY SNEAK PEEK: LEGAL TOOLS TO SPEEDING UP LIGHTMAPS DISCREET 3DS MAX 7 PROTECT YOUR I.P. WITH PIXEL SHADERS POSTMORTEM: THE CINEMATIC EFFECT OF ZOMBIE STUDIOS’ SHADOW OPS: RED MERCURY []CONTENTS AUGUST 2004 VOLUME 11, NUMBER 7 FEATURES 14 COPYRIGHT: THE BIG GUN FOR GAME DEVELOPERS A one-of-a-kind game concept, an instantly recognizable character, a clever phrase— these are all a game developer’s most valuable assets. To protect such intangible properties from pirates, you’ll need to bring out the big gun—copyright. Here’s some free advice from a lawyer. By S. Gregory Boyd 20 FAST RADIOSITY: USING PIXEL SHADERS 14 With the latest advances in hardware, GPU, 34 and graphics technology, it’s time to take another look at lightmapping, the divine art of illuminating a digital environment. By Brian Ramage 20 POSTMORTEM 30 FROM BUNGIE TO WIDELOAD, SEROPIAN’S BEAT GOES ON 34 THE CINEMATIC EFFECT OF ZOMBIE STUDIOS’ A decade ago, Alexander Seropian founded a SHADOW OPS: RED MERCURY one-man company called Bungie, the studio that would eventually give us MYTH, ONI, and How do you give a player that vicarious presence in an imaginary HALO. Now, after his departure from Bungie, environment—that “you-are-there” feeling that a good movie often gives? he’s trying to repeat history by starting a new Zombie’s answer was to adopt many of the standard movie production studio: Wideload Games. -

Press Release (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y 14 December 2015 My camera and I, together we have the power to confer or to take away. —Richard Avedon They always say that time changes things, but you actually have to change them yourself. —Andy Warhol Gagosian London is pleased to present the first major exhibition to pair works by Richard Avedon and Andy Warhol. Both artists rose to prominence in postwar America with parallel artistic output that occasionally overlapped. Their most memorable images, produced in response to changing cultural mores, are icons of the twentieth century. Portraiture was a shared focus of both artists, and they made use of repetition and serialization: Avedon through the reproducible medium of photography, and in his group photographs, for which he meticulously positioned, collaged, and reordered images; Warhol in his method of stacked screenprinting, which enabled the consistent reproduction of an image. Avedon’s distinctive gelatin-silver prints and Warhol's boldly colored silkscreens variously depict many of the same recognizable faces, including Marella Agnelli, Bianca Jagger, Jacqueline Kennedy, Marilyn Monroe, and Rudolf Nureyev. Both Avedon and Warhol originated from modest beginnings and had tremendous commercial success working for major magazines in New York, beginning in the 1940s. The 1960s marked artistic turning points for both artists as they moved away increasingly from strictly commercial work towards their mature independent styles. The works in the exhibition, which date from the 1950s through the 1990s, emphasize such common themes as social and political power; the evolving acceptance of cultural differences; the inevitability of mortality; and the glamour and despair of celebrity.