Modeled O2 Nightglow Distributions in the Venusian Atmosphere Marie-Ève Gagné,1,2 Stella M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campus Distinctions by Highest Number Met

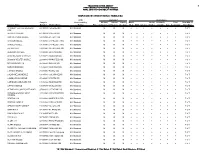

TEXAS EDUCATION AGENCY 1 PERFORMANCE REPORTING DIVISION FINAL 2018 ACCOUNTABILITY RATINGS CAMPUS DISTINCTIONS BY HIGHEST NUMBER MET 2018 Domains* Distinctions Campus Accountability Student School Closing Read/ Social Academic Post Num Met of Campus Name Number District Name Rating Note Achievement Progress the Gaps ELA Math Science Studies Growth Gap Secondary Num Eval ACADEMY FOR TECHNOLOGY 221901010 ABILENE ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ENG ALICIA R CHACON 071905138 YSLETA ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ANN RICHARDS MIDDLE 108912045 LA JOYA ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ARAGON MIDDLE 101907051 CYPRESS-FAIRB Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ARNOLD MIDDLE 101907041 CYPRESS-FAIRB Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 B L GRAY J H 108911041 SHARYLAND ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BENJAMIN SCHOOL 138904001 BENJAMIN ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BRIARMEADOW CHARTER 101912344 HOUSTON ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BROOKS WESTER MIDDLE 220908043 MANSFIELD ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BRYAN ADAMS H S 057905001 DALLAS ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BURBANK MIDDLE 101912043 HOUSTON ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 C M RICE MIDDLE 043910053 PLANO ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 CALVIN NELMS MIDDLE 101837041 CALVIN NELMS Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 CAMINO REAL MIDDLE 071905051 YSLETA ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 CARNEGIE VANGUARD H S 101912322 HOUSTON ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● -

Workshop on Moon in Transition: Apollo 14, Kreep, and Evolved Lunar Rocks

WORKSHOP ON MOON IN TRANSITION: APOLLO 14, KREEP, AND EVOLVED LUNAR ROCKS (NASA-CR-I"'-- N90-I_02o rRAN31TION: APJLLN l_p KRFEP, ANu _VOLVFD LUNAR ROCKS (Lunar and Pl_net3ry !nst.) I_7 p C_CL O3B Unclas G3/91 0253133 LPI Technical Report Number 89-03 UNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE 3303 NASA ROAD 1 HOUSTON, TEXAS 77058-4399 7 WORKSHOP ON MOON IN TRANSITION: APOLLO 14, KREEP, AND EVOLVED LUNAR ROCKS Edited by G. J. Taylor and P. H. Warren Sponsored by Lunar and Planetary Institute NASA Johnson Space Center November 14-16, 1988 Houston, Texas Lunar and Planetary Institute 330 ?_NASA Road 1 Houston, Texas 77058-4399 LPI Technical Report Number 89-03 Compiled in 1989 by the LUNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE The Institute is operated by Universities Space Research Association under Contract NASW-4066 with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Material in this document may be copied without restraint for Library, abstract service, educational, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any portion requires the written permission of the authors as well as appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. This report may be cited as: Taylor G. J. and Warren PI H., eds. (1989) Workshop on Moon in Transition: Apo{l_ 14 KREEP, and Evolved Lunar Rocks. [PI Tech. Rpt. 89-03. Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. 156 pp. Papers in this report may be cited as: Author A. A. (1989) Title of paper. In W_nkshop on Moon in Transition: Ap_llo 14, KREEP, and Evolved Lunar Rocks (G. J. Taylor and P. H. Warren, eds.), pp. xx-yy. LPI Tech. Rpt. -

A Discussion of Co and 0 on Venus and Mars

, >::. X·620.,J2-209 PREPRINT ~ '. , A DISCUSSION OF CO AND 0 ON VENUS AND MARS - (NASA-T8-X-65950) A DISCUSSION OF CO AND 0 N72-28848 ON VENUS AND MARS M. Shimizu (NASA) Jun. 1972 24 p CSCL 03B Unclas G3/30 36042 MIKIO SHIMIZU JUNE 1972 -- GODDARD SPACE fLIGHT CENTER -- GREENBE~T, MARYLAND I Roproduced by NATIONAL TECHNICAL INFORMATION SERVICE us Dcparlmont 0/ Comm"rc" Springfield, VA. 22151 ~- --- -I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I A DISCUSSION OF CO AND 0 ON VENUS AND MARS by Mikio Shimizu* Laboratory for Planetary Atmospheres Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland * NAS-NRC Senior Research Associate, on leave from ISAS, The University of Tokyo -I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I ABSTRACT The absorption of solar ultraviolet radiation in the wavelength o range 2000 - 2200 A by CO 2 strongly reduces the dissociation rate of HC1 on Venus. The C1 catalytic reaction for the rapid recombination of o and CO and the yellow coloration of the Venus haze by OC1 and C1 3 a~pears to be unlikely. At the time of the Martian dust storm, the dissociation of H20 in the vicinity of the surface may vanish. -

Fall 2014 New York City Campus Dean's List

DYSON COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DEAN'S LIST NEW YORK CITY CAMPUS FALL 2014 First Honors Second Honors Third Honors Brandon Adam Cristian Abbrancati Elizabeth A. Abere Pamela Marianelli V. Agbulos Katrina Abreu Yasmine Achibat Nanichi Aguado Foy Mirandah E. Ackley Kayla R. Adens Fatima A. Ahmed Daria Afanaseva Raphael E. Ades-Aron Tiffany Amaro Salazar Yasamin Aftahi Diana D. Akelin Shabena N. Amzad Melissa Agosto Fathima Z. Alam Alexander R. Angelis Marine Alaberkian Ariana M. Alexander Shivani A. Annirood Alanoud A. Alammar Tania G. Ali Kseniya Arekhava Veronica R. Albarella Lucas M. Allen Shalynne A. Armstrong Shimma I. Almabruk Jennifer Almanzar Isabella M. Asali Rania I. Alrashoodi Michael B. Andersen Samuel W. Ashby Polina Altunina Ashley M. Aquilo Malek Assad Cody N. Alvord Alexis G. Argentine Sabeen Aziz Kerstin B. Anderson Abbey E. Ashley Stefanie C. Bacarella Alexandra L. Anschutz Marayah A. Ayoub-Schreifeldt Cara Badalamenti Savannah R. Apple Tiffany C. Babb Maria G. Baker Gabriel D. Armentano Kathryn M. Balitsos Ryan E. Barone Joshua L. Arnold Carlina S. Baptista Amani J. Basaeed Ami H. Asakawa Lucia A. Barneche Yousra Bashir Solmaz Azimi Michael A. Basil Allison E. Bass Antonina M. Bacchi Marie A. Basile Ryan C. Beaghler Michelle Back Garth O. Bates Katherine Becker Galia J. Backal Ayanna R. Bates Katherine D. Behm Connie Bahng Dahnay O. Bazunu Marilyn H. Beichner Adena E. Baichan Ashley A. Beadle Suzanne E. Beiter Matthew S. Bailey Latiana J. Blue Anastasia Beliakova Sylwia B. Baj Maria V. Borgo Adrienne R. Bengtsson Conor J. Baker Amber P. Brazil Thomas April S. Benshoshan Elisabeth Balachova Conor J. -

Florida Atlantic University

FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY Commencement Classes d196S -1969 Sunday, June 8, 1969 Two o'Clock THE CAMPUS Boca Raton, Florida !fJrogram Prelude Prelude and Fugue in C. Major- ]. S. Bach Processional Pomp and Circumstance- Edward Elgar B. Graham Ellerbee, Organist Introductions Dr. Clyde R. Burnett University Marshal Invocation The Rev. Donald Barrus United Campus Ministries National Anthem - Key- Sousa Richard Wright Instructor in Music Presiding Dr. Kenneth R. Williams President Florida Atlantic University Address "The Generation of City Builders" Dr. Robert C. Wood Director Joint Center for Urban Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Presentation of Baccalaureate Degrees Dr. S. E. Wimberly Vice President for Academic Affairs For the College of Business and Public Administration Dean Robert L. Froemke For the College of Education Dean Robert R. Wiegman For the College of Humanities Dean Jack Suberman For the Department of Ocean Engineering Professor Charles R. Stephan For the College of Science Dean Kenneth M. Michels For the College of Social Science Dean John M. DeGrove Presentation of the Master of Education, Master of Public Administration, Master of Science and Master of Arts Degrees Deans of the Respective Colleges Benediction The Reverend Barrus Recessional Recessional - Martin Shaw The Audience will please remain in their places until the Faculty and Graduates have left the area. 1 THE ORDER OF THE PROCE SS IO N The Marshal of the Colleges The Marshals and Candidates of the College of Business and Public Administration -

Venus Mesosphere and Thermosphere II. Global Circulation

ICARUS 68, 284--312 (1986) Venus Mesosphere and Thermosphere II. Global Circulation, Temperature, and Density Variations S. W. BOUGHER,*'t R. E. DICKINSON,$ E. C. RIDLEY,§ R. G. ROBLE,* A. F. NAGY, II AND T. E. CRAVENS II *High Altitude Observatory, ~fAdvanced Study Program, $Atmospheric Analysis and Prediction, and §Scientific Computing Division, National Center for Atmospheric Research, I P.O. Box 3000, Boulder, Colorado 80307; and IISpace Physics Research Laboratory, 2455 Hayward, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 Received February 13, 1986; revised July 11, 1986 Recent Pioneer Venus observations have prompted a return to comprehensive hydrodynamical modeling of the thermosphere of Venus. Our approach has been to reexamine the circulation and structure of the thermosphere using the framework of the R. E. Dickinson and E. C. Ridley (1977, Icarus 30, 163-178), symmetric two-dimensional model. Sensitivity tests were conducted to see how large-scale winds, eddy diffusion and conduction, and strong 15-/xm cooling affect day-night contrasts of densities and temperatures. The calculated densities and temperatures are compared to symmetric empirical model fields constructed from the Pioneer Venus data base. We find that the observed day-to-night variation of composition and temperatures can be derived largely by a wave- drag parameterization that gives a circulation system weaker than predicted prior to Pioneer Venus. The calculated mesospheric winds are consistent with Earth-based observations near 115 km. Our studies also suggest that eddy diffusion is only a minor contributor to the maintenance of observed day and nightside densities, and that eddy coefficients are smaller than values used by previous one-dimensional composition models. -

Fluid Outflows from Venus Impact Craters

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 97, NO. E8, PAGES 13,643-13,665 AUGUST 25, 1992 Fluid Outflows From Venus Impact Craters' AnalysisFrom Magellan Data PAUL D. A SIMOW1 Departmentof Earth and Planeta .rySciences, ttarvard Universi.ty,Cambridge, Massachusetts JOHN A. WOOD SmithsonianAstrophysical Observato .rv, Cambridge, Massachusetts Many impactcraters on Venushave unusualoutflow features originating in or underthe continuousejecta blanketsand continuing downhill into the surroundingterrain. Thesefeatures clearly resulted from flow of low- viscosityfluids, but the identityof thosefluids is not clear. In particular,it shouldnot be assumeda priori that the fluid is an impact melt. A numberof candidateprocesses by which impact eventsmight generatethe observedfeatures are considered,and predictionsare made concerningthe theologicalcharacter of flows producedby each mechanism. A sampleof outflowswas analyzedusing Magellan imagesand a model of unconstrainedBingham plastic flow on inclinedplanes, leading to estimatesof viscosityand yield strengthfor the flow materials. It is arguedthat at leasttwo different mechanismshave producedoutflows on Venus: an erosive,channel-forming process and a depositionalprocess. The erosivefluid is probablyan impactmelt, but the depositionalfluid may consistof fluidizedsolid debris, vaporized material, and/or melt. INTRODUCTION extremelydiverse in appearanceand may representmore than one distinctprocess and/or material. Recentlyacquired high-resolution radar images of Venusfrom the Magellan spacecraft have revealed surface features in unprecedenteddetail. In addition to new views of previously SETtING AND MORPHOLOGY OF VENUS CRATER OUTFLOW known features,a seriesof completelynew and often enigmatic FEATURES features have been discovered. Among the new phenomena Over 800 impactcraters were identifiedin imagesproduced by observed,the characterof ejecta depositsaround impact craters the Magellan missionduring its first cycle of orbital mapping, ranks as one of the most enigmatic. -

Transfers 2020

City of Petersburg Transfers 1/1/2020 - 12/31/2020 Use Parcel Property Address Grantor Grantee Code Transfer Dat Consideration 1010900043834 Allegheny AveMORING,EDWARD E SHIRLEY G LUCAS ENTERPRISES LLC 400 1/21/2020 $25,000.00 0562000082316 Anderson StHARRIS,JAMES JANICE MAE HARRIS 101 5/13/2020 $0.00 0562000092322 Anderson StTHE PRIME EQUITY GROUP LLC, KIARRA R COX-BLAND 101 4/22/2020 $143,900.00 0542400081859 Arch StCOLE,BENJAMIN L CENTRAL VA HOME IMPROVEMENT LLC 101 6/2/2020 $65,000.00 0542800071875 Arch StJR PROPERTY INVESTORS LLC, GEORGE ARTHUR FERNANDEZ & KARLA J 101 7/6/2020 $174,900.00 0452100071196 Arlington StFAITH INVESTMENTS FOUNDATION INC, FAITH INVESTMENTS LLC 101 3/18/2020 $0.00 029190002819 Augusta AveWHEATLEY,CLIFFORD SG-GARLAND AVE LLC 101 3/30/2020 $44,000.00 029170020836 Augusta AveBROWN,PHYLLIS BLAND 836 AUGUSTA AVENUE SERIES 101 2/25/2020 $40,001.00 0453800191325 Baylors LnCARROLL,RAMONDA CHRISTINA WHITTEN-AMADON 101 3/2/2020 $76,000.00 0453600051430 Baylors LnSTEWART,ELBERT C KIMBERLY ANN ET ALS STEWART 101 1/15/2020 $0.00 066030010327 Beauregard AveDORR,LUCY R PAMELA D SHANDS 101 4/22/2020 $188,000.00 066020002408 Beauregard AveWOOTEN,MARIAN M DERRICK COAXUM 101 2/28/2020 $113,007.00 066020002408 Beauregard AveSECRETARY OF HSG & URBAN DEV, DERRICK COAXUM 101 6/30/2020 $122,000.00 067140012437 Beauregard AveLAKEVIEW LOAN SVCG LLC, GAP INVESTMENTS LLC 101 6/19/2020 $104,900.00 047140018423 Beech StWALKER,SHARON D SHARON DENISE WALKER & SELWYN A W 201 5/29/2020 $0.00 City of Petersburg Transfers 1/1/2020 - 12/31/2020 -

Minutes: August 17-18, 2020

NASAADVISORY COUNCIL PLANETARYSCIENCEADVISORYCOMMITTEE August 17-18, 2020 NASAHeadquarters Washington, DC MEETINGREPORT Anne Verbiscer, Chair STEPHENRINEHA RTDigitallysignedbySTEPHENRINEHART Date:2020.10.021 8.::38.::37-04'00" Stephen Rinehart , Executive Secretary Table of Contents Opening and Announcements, Introductions 3 PSD Status Report 3 PSD R&A Status 6 Planetary Decadal Survey Update 8 Mars Exploration Program 9 Mars Sample Return 11 Lunar Program/ESSIO 11 VIPER 13 Planetary Defense Coordination Office 13 GPRAMA 14 Discussion 14 ExoPAG 15 CAPTEM 15 LEAG 15 MAPSIT 16 SBAG 17 MExAG 18 OPAG 18 VEXAG 19 MEPAG 20 Findings and Recommendations Discussion 20 Public Comment 22 Discussion/Wrap-up 22 Appendix A- Attendees Appendix B- Membership roster Appendix C- Agenda Appendix D- Presentations Prepared by Joan M. Zimmermann Zantech, Inc. August 17, 2020 2 Opening and Announcements, Introductions Executive Secretary of the Planetary Science Advisory Committee (PAC), Dr. Stephen Rinehart welcomed members of the committee and held a roll call, noting that this is the last meeting for a number of members: Drs. Anne Verbiscer (PAC Chair), Timothy Lyons, Robin Canup, Rhonda Stroud, Francis McCubbin, Aki Roberge, and Chris German. New members coming on board are: Drs. Joseph Westlake, Jennifer Glass, Serina Diniega, and Conor Nixon. Dr. Amy Mainzer will become the new PAC Chair. PSD Status Report Dr. Lori Glaze, Director of the Planetary Science Division (PSD), presented an update on the division, tendered her thanks to the PAC members rolling off, and reported that the new PAC members are in their final phase of confirmation paperwork. Dr. Glaze announced newly arrived staff at PSD: Drs. -

Adirondack Chronology

An Adirondack Chronology by The Adirondack Research Library of the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks Chronology Management Team Gary Chilson Professor of Environmental Studies Editor, The Adirondack Journal of Environmental Studies Paul Smith’s College of Arts and Sciences PO Box 265 Paul Smiths, NY 12970-0265 [email protected] Carl George Professor of Biology, Emeritus Department of Biology Union College Schenectady, NY 12308 [email protected] Richard Tucker Adirondack Research Library 897 St. David’s Lane Niskayuna, NY 12309 [email protected] Last revised and enlarged – 20 January (No. 43) www.protectadks.org Adirondack Research Library The Adirondack Chronology is a useful resource for researchers and all others interested in the Adirondacks. It is made available by the Adirondack Research Library (ARL) of the Association for the Protection of the Adirondacks. It is hoped that it may serve as a 'starter set' of basic information leading to more in-depth research. Can the ARL further serve your research needs? To find out, visit our web page, or even better, visit the ARL at the Center for the Forest Preserve, 897 St. David's Lane, Niskayuna, N.Y., 12309. The ARL houses one of the finest collections available of books and periodicals, manuscripts, maps, photographs, and private papers dealing with the Adirondacks. Its volunteers will gladly assist you in finding answers to your questions and locating materials and contacts for your research projects. Introduction Is a chronology of the Adirondacks really possible? -

Hamilton, W. B., Plumeless Venus Preserves an Ancient Impact

Geological Society of America Special Paper 388 2005 Plumeless Venus preserves an ancient impact-accretionary surface Warren B. Hamilton* Department of Geophysics, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, Colorado 80401, USA ABSTRACT Venus displays thousands of old circular structures, with topographic rims 5– 2000 km in diameter, that have the morphology and cookie-cutter superposition required of impact craters and basins. Many structures have interior central or ring uplifts or broad, low volcanic constructs. Many are multiring. Old uplands are satu- rated with variably degraded structures, whereas lowland structures are variably buried by sediments. The youngest include three of the largest (rim diameters of 800–2000 km), for which analogy with the dated Imbrium impact basin on the Moon indicates likely ages of ca. 3.90 Ga. Venus is argued here to preserve much of its sur- face of late-stage main planetary accretion. The Venus of conventional interpretation, by contrast, was wholly resurfaced, mostly by plume-driven processes, no earlier than 1 Ga, and preserves no ancient fea- tures. This speculation is extrapolated from terrestrial conjectures, and rationalizes away voluminous contrary evidence from Venus itself. Interpreters of early Venusian radar imagery accepted the possible impact origin and great age of the structures, but impact explanations were soon replaced, almost without analysis, by plume conjectures. Nearly all specialists now assume that Venus has internal mobility comparable to the exaggerated mobility assumed for Earth, and that the only Venusian impact structures are “pristine” small- to mid-size craters and basins with an age younger than 1.0 Ga. (Ages to 3.9 Ga for these are advocated here.) The older circular structures are con- ventionally attributed to mantle plumes and upwellings that deformed crust and upper mantle from beneath, with or without lava extrusion. -

U.S. Senate and House ·:Ca.Ndidates

r •rt") (/ ' ] : J · Yufi..\~ ~~1 I ~1 ·~ y • • ~ "ID~ N0\?.01\c:Vt- · j ~ -::::r' .....__. ):: ~ .J l. j i] i i ] / . I . .. ,/" ] PAC.Mone-y :- .. ] ... Contributed to ' 'l .' t~\.... • I ! U.S. Senate., and 1.'! ''] House ; ·:Ca.ndidates . lI ... ,.•. 1977-1982 ! .1 / . J, .. J ·<· I . .·- r . ·.~. .. l .J . l .J FEDERAL ELECTION COMMISSION 1325 K Street, N.W. ll· Wash~n, D.C. '20463 ~J ' .• t,~ .~. .. l OCTOBER 1984 -:-). \ . ,AI. PAC MONEY CONTRIBUTED TO U.S. SENATE AND HOUSE CANDIDATES 1977-1982 The following information is taken from previously published FEC Reports on Financial Activity - U.S. Senate and House Campaigns: 1981-1982 Final Report, 1979-1980 Final Report, and 1977-1978 Interim Report No.5. • Within each election cycle, Senate candidates are listed separately from House candidates. Each list is in descending order by the amount of PAC money given to a candidate. Where equal amounts are shown for two or more candidates, the candidates are listed in alphabetical order. • Two-year PAC money figures are listed only for candidates involved in a particular election cycle. Therefore, the listings do not include PAC money given to candidates who were not seeking election or re-election during those two years, (for example, Senate candidates or retiring House members.) • Negative amounts indicate PAC contributions returned by a candidate in excess of what he or she may have received. This often occurs when money was received in one election cycle and returned in another cycle. Copies may be obtained from the Federal Election Commission, Public Records Office, 1325 K Street, N.