Venus Mesosphere and Thermosphere II. Global Circulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nighttime Secondary Ozone Layer During Major Stratospheric Sudden Warmings in Specified-Dynamics WACCM Olga V

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH: ATMOSPHERES, VOL. 118, 8346–8358, doi:10.1002/jgrd.50651, 2013 Nighttime secondary ozone layer during major stratospheric sudden warmings in specified-dynamics WACCM Olga V. Tweedy,1,2 Varavut Limpasuvan,1 Yvan J. Orsolini,3,4 Anne K. Smith,5 Rolando R. Garcia,5 Doug Kinnison,5 Cora E. Randall,6,7 Ole-Kristian Kvissel,8 Frode Stordal,8 V. Lynn Harvey,6,7 and Amal Chandran 9 Received 26 March 2013; revised 5 July 2013; accepted 15 July 2013; published 9 August 2013. [1] A major stratospheric sudden warming (SSW) strongly impacts the entire middle atmosphere up to the thermosphere. Currently, the role of atmospheric dynamics on polar ozone in the mesosphere-lower thermosphere (MLT) during SSWs is not well understood. Here we investigate the SSW-induced changes in the nighttime “secondary” (90–105 km) ozone maximum by examining the dynamics and distribution of key species (like H and O) important to ozone. We use output from the National Center for Atmospheric Research Whole Atmosphere Community Climate Model with “Specified Dynamics” (SD-WACCM), in which the simulation is constrained by meteorological reanalyses below 1 hPa. Composites are made based on six major SSW events with elevated stratopause episodes. Individual SSW cases of temperature and MLT nighttime ozone from the model are compared against the Sounding of the Atmosphere using Broadband Emission Radiometry observations aboard the NASA’s Thermosphere Ionosphere Mesosphere Energetics and Dynamics (TIMED) satellite. The evolution of ozone and major chemical trace species is associated with the anomalous vertical residual motion during SSWs and consistent with photochemical equilibrium governing the MLT nighttime ozone. -

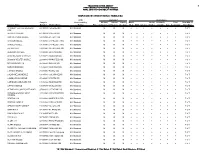

Campus Distinctions by Highest Number Met

TEXAS EDUCATION AGENCY 1 PERFORMANCE REPORTING DIVISION FINAL 2018 ACCOUNTABILITY RATINGS CAMPUS DISTINCTIONS BY HIGHEST NUMBER MET 2018 Domains* Distinctions Campus Accountability Student School Closing Read/ Social Academic Post Num Met of Campus Name Number District Name Rating Note Achievement Progress the Gaps ELA Math Science Studies Growth Gap Secondary Num Eval ACADEMY FOR TECHNOLOGY 221901010 ABILENE ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ENG ALICIA R CHACON 071905138 YSLETA ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ANN RICHARDS MIDDLE 108912045 LA JOYA ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ARAGON MIDDLE 101907051 CYPRESS-FAIRB Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ARNOLD MIDDLE 101907041 CYPRESS-FAIRB Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 B L GRAY J H 108911041 SHARYLAND ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BENJAMIN SCHOOL 138904001 BENJAMIN ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BRIARMEADOW CHARTER 101912344 HOUSTON ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BROOKS WESTER MIDDLE 220908043 MANSFIELD ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BRYAN ADAMS H S 057905001 DALLAS ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BURBANK MIDDLE 101912043 HOUSTON ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 C M RICE MIDDLE 043910053 PLANO ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 CALVIN NELMS MIDDLE 101837041 CALVIN NELMS Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 CAMINO REAL MIDDLE 071905051 YSLETA ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 CARNEGIE VANGUARD H S 101912322 HOUSTON ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● -

Workshop on Moon in Transition: Apollo 14, Kreep, and Evolved Lunar Rocks

WORKSHOP ON MOON IN TRANSITION: APOLLO 14, KREEP, AND EVOLVED LUNAR ROCKS (NASA-CR-I"'-- N90-I_02o rRAN31TION: APJLLN l_p KRFEP, ANu _VOLVFD LUNAR ROCKS (Lunar and Pl_net3ry !nst.) I_7 p C_CL O3B Unclas G3/91 0253133 LPI Technical Report Number 89-03 UNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE 3303 NASA ROAD 1 HOUSTON, TEXAS 77058-4399 7 WORKSHOP ON MOON IN TRANSITION: APOLLO 14, KREEP, AND EVOLVED LUNAR ROCKS Edited by G. J. Taylor and P. H. Warren Sponsored by Lunar and Planetary Institute NASA Johnson Space Center November 14-16, 1988 Houston, Texas Lunar and Planetary Institute 330 ?_NASA Road 1 Houston, Texas 77058-4399 LPI Technical Report Number 89-03 Compiled in 1989 by the LUNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE The Institute is operated by Universities Space Research Association under Contract NASW-4066 with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Material in this document may be copied without restraint for Library, abstract service, educational, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any portion requires the written permission of the authors as well as appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. This report may be cited as: Taylor G. J. and Warren PI H., eds. (1989) Workshop on Moon in Transition: Apo{l_ 14 KREEP, and Evolved Lunar Rocks. [PI Tech. Rpt. 89-03. Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. 156 pp. Papers in this report may be cited as: Author A. A. (1989) Title of paper. In W_nkshop on Moon in Transition: Ap_llo 14, KREEP, and Evolved Lunar Rocks (G. J. Taylor and P. H. Warren, eds.), pp. xx-yy. LPI Tech. Rpt. -

A Discussion of Co and 0 on Venus and Mars

, >::. X·620.,J2-209 PREPRINT ~ '. , A DISCUSSION OF CO AND 0 ON VENUS AND MARS - (NASA-T8-X-65950) A DISCUSSION OF CO AND 0 N72-28848 ON VENUS AND MARS M. Shimizu (NASA) Jun. 1972 24 p CSCL 03B Unclas G3/30 36042 MIKIO SHIMIZU JUNE 1972 -- GODDARD SPACE fLIGHT CENTER -- GREENBE~T, MARYLAND I Roproduced by NATIONAL TECHNICAL INFORMATION SERVICE us Dcparlmont 0/ Comm"rc" Springfield, VA. 22151 ~- --- -I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I A DISCUSSION OF CO AND 0 ON VENUS AND MARS by Mikio Shimizu* Laboratory for Planetary Atmospheres Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland * NAS-NRC Senior Research Associate, on leave from ISAS, The University of Tokyo -I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I ABSTRACT The absorption of solar ultraviolet radiation in the wavelength o range 2000 - 2200 A by CO 2 strongly reduces the dissociation rate of HC1 on Venus. The C1 catalytic reaction for the rapid recombination of o and CO and the yellow coloration of the Venus haze by OC1 and C1 3 a~pears to be unlikely. At the time of the Martian dust storm, the dissociation of H20 in the vicinity of the surface may vanish. -

Fall 2014 New York City Campus Dean's List

DYSON COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DEAN'S LIST NEW YORK CITY CAMPUS FALL 2014 First Honors Second Honors Third Honors Brandon Adam Cristian Abbrancati Elizabeth A. Abere Pamela Marianelli V. Agbulos Katrina Abreu Yasmine Achibat Nanichi Aguado Foy Mirandah E. Ackley Kayla R. Adens Fatima A. Ahmed Daria Afanaseva Raphael E. Ades-Aron Tiffany Amaro Salazar Yasamin Aftahi Diana D. Akelin Shabena N. Amzad Melissa Agosto Fathima Z. Alam Alexander R. Angelis Marine Alaberkian Ariana M. Alexander Shivani A. Annirood Alanoud A. Alammar Tania G. Ali Kseniya Arekhava Veronica R. Albarella Lucas M. Allen Shalynne A. Armstrong Shimma I. Almabruk Jennifer Almanzar Isabella M. Asali Rania I. Alrashoodi Michael B. Andersen Samuel W. Ashby Polina Altunina Ashley M. Aquilo Malek Assad Cody N. Alvord Alexis G. Argentine Sabeen Aziz Kerstin B. Anderson Abbey E. Ashley Stefanie C. Bacarella Alexandra L. Anschutz Marayah A. Ayoub-Schreifeldt Cara Badalamenti Savannah R. Apple Tiffany C. Babb Maria G. Baker Gabriel D. Armentano Kathryn M. Balitsos Ryan E. Barone Joshua L. Arnold Carlina S. Baptista Amani J. Basaeed Ami H. Asakawa Lucia A. Barneche Yousra Bashir Solmaz Azimi Michael A. Basil Allison E. Bass Antonina M. Bacchi Marie A. Basile Ryan C. Beaghler Michelle Back Garth O. Bates Katherine Becker Galia J. Backal Ayanna R. Bates Katherine D. Behm Connie Bahng Dahnay O. Bazunu Marilyn H. Beichner Adena E. Baichan Ashley A. Beadle Suzanne E. Beiter Matthew S. Bailey Latiana J. Blue Anastasia Beliakova Sylwia B. Baj Maria V. Borgo Adrienne R. Bengtsson Conor J. Baker Amber P. Brazil Thomas April S. Benshoshan Elisabeth Balachova Conor J. -

Florida Atlantic University

FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY Commencement Classes d196S -1969 Sunday, June 8, 1969 Two o'Clock THE CAMPUS Boca Raton, Florida !fJrogram Prelude Prelude and Fugue in C. Major- ]. S. Bach Processional Pomp and Circumstance- Edward Elgar B. Graham Ellerbee, Organist Introductions Dr. Clyde R. Burnett University Marshal Invocation The Rev. Donald Barrus United Campus Ministries National Anthem - Key- Sousa Richard Wright Instructor in Music Presiding Dr. Kenneth R. Williams President Florida Atlantic University Address "The Generation of City Builders" Dr. Robert C. Wood Director Joint Center for Urban Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Presentation of Baccalaureate Degrees Dr. S. E. Wimberly Vice President for Academic Affairs For the College of Business and Public Administration Dean Robert L. Froemke For the College of Education Dean Robert R. Wiegman For the College of Humanities Dean Jack Suberman For the Department of Ocean Engineering Professor Charles R. Stephan For the College of Science Dean Kenneth M. Michels For the College of Social Science Dean John M. DeGrove Presentation of the Master of Education, Master of Public Administration, Master of Science and Master of Arts Degrees Deans of the Respective Colleges Benediction The Reverend Barrus Recessional Recessional - Martin Shaw The Audience will please remain in their places until the Faculty and Graduates have left the area. 1 THE ORDER OF THE PROCE SS IO N The Marshal of the Colleges The Marshals and Candidates of the College of Business and Public Administration -

Response of the Mesosphere-Thermosphere- Ionosphere System to Global Change - CAWSES-II Contribution Jan Laštovička1*, Gufran Beig2 and Daniel R Marsh3

Laštovička et al. Progress in Earth and Planetary Science 2014, 1:21 http://www.progearthplanetsci.com/content/1/1/21 REVIEW Open Access Response of the mesosphere-thermosphere- ionosphere system to global change - CAWSES-II contribution Jan Laštovička1*, Gufran Beig2 and Daniel R Marsh3 Abstract Long-term trends in the mesosphere, thermosphere, and ionosphere are areas of research of increasing importance both because they are sensitive indicators of climatic change and because they affect satellite-based technologies which are increasingly important to modern life. Their study was an important part of CAWSES-II project, as they were a topic of Task Group 2 (TG-2) ‘How Will Geospace Respond to Changing Climate’. Three individual projects of TG-2 were focused on important problems in trend investigations. Significant progress was reached in several areas such as understanding and quantifying the role of stratospheric ozone changes in trends in the upper atmosphere, reaching reasonable agreement between observed and simulated trends in mesospheric temperatures and polar mesospheric clouds, or understanding of why the thermospheric density trends are much stronger under solar cycle minimum conditions. The TG-2 progress that is reviewed in this paper together with some results reached outside CAWSES-II so as to have the full context of progress in trends in the upper atmosphere and ionosphere. Keywords: Mesosphere; Thermosphere; Ionosphere; Long-term trends; Climatic change Review Laštovička et al. 2012). The thermosphere is the operating Introduction environment of many satellites, including the Inter- The anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases carbon national Space Station, and thousands of pieces of danger- dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O) ous space debris, the orbital lifetime of which depends on influence the troposphere, weather, and particularly cli- long-term changes of thermospheric density. -

The Upper Atmosphere of Venus Observed by Venus Express

THE UPPER ATMOSPHERE OF VENUS OBSERVED BY VENUS EXPRESS MIGUEL A. LOPEZ-VALVERDE´ , GABRIELLA GILLI, MAYA GARC´IA-COMAS Departamento Sistema Solar, Instituto de Astrof´ısica de Andaluc´ıa–Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cient´ıficas (CSIC), E-18008 Granada, SPAIN FRANCISCO GONZALEZ-GALINDO´ Laboratoire de Meteorologie Dynamique, Institut Pierre Simon Laplace, Paris, France PIERRE DROSSART LESIA, Observatoire de Paris-Meudon, UMR 8109 F-92190 Paris, France GIUSEPPE PICCIONI IASF-INAF, via del Fosso del Cavalliere 100, 00103 Rome, Italy AND THE VIRTIS/VENUS EXPRESS TEAM Abstract: The upper atmosphere of Venus is still nowadays a highly unknown region in the scientific context of the terrestrial planetary atmospheres. The Earth’s stratosphere and mesosphere continue being studied with increasingly sophisticated sounders and in-situ instrumentation [1, 2]. Also on Mars, its intensive on-going exploration is gathering a whole new set of data on its upper atmosphere [3, 4, 5]. On Venus, however, the only recent progress came from theoretical model developments, from ground observations and from revisits of past missions’ data, like Pioneer Venus. More and new data are needed [6, 7, 8]. The arrival of the European Venus Express (VEX) mission at Venus on April 2006 marked the start of an exciting period with new data from a systematic sounding of the Venus atmosphere from orbit [9, 10]. A suite of diverse instrumentation is obtaining new observations of the atmosphere of Venus. After one and a half years in orbit, and although the data are still under validation and extensive analysis, first results are starting to be published. In addition to those global descriptions of VEX and its first achievements, we present here a review on what VEX data are adding to the exploration of this upper region of the atmosphere of Venus. -

Layers of the Atmosphere

Name ________________________ Layers of the Atmosphere By Jack Fearing, Lincoln Junior High School, Hibbing, Minnesota OBJECTIVE: To discover how the atmosphere can be divided into layers based on temperature changes at different heights, by making a graph. BACKGROUND: The atmosphere can be divided into four layers based on temperature variations. The layer closest to the Earth is called the troposphere. Above this layer is the stratosphere, followed by the mesosphere, then the thermosphere. The upper boundaries between these layers are known as the tropopause, the stratopause, and the mesopause, respectively. Temperature variations in the four layers are due to the way solar energy is absorbed as it moves downward through the atmosphere. The Earth’s surface is the primary absorber of solar energy. Some of this energy is reradiated by the Earth as heat, which warms the overlying troposphere. The global average temperature in the troposphere rapidly decreases with altitude until the tropopause, the boundary between the troposphere and the stratosphere. The temperature begins to increase with altitude in the stratosphere. This warming is caused by a form of oxygen called ozone (O3) absorbing ultraviolet radiation from the sun. Ozone protects us from most of the sun’s ultraviolet radiation, which can cause cancer, genetic mutations, and sunburn. Scientists are concerned that human activity is contributing to a decrease in stratospheric ozone. Nitric oxide, which is the exhaust of high-flying jets, and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs), which are used as refrigerants, may contribute to ozone depletion. At the stratopause, the temperature stops increasing with altitude. The overlying mesosphere does not absorb solar radiation, so the temperature decreases with altitude. -

Venus Voyage 2050 White Paper Wilson, Widemann Et Al

Venus Voyage 2050 White Paper Wilson, Widemann et al. August 2019 Venus: Key to understanding the evolution of terrestrial planets A response to ESA’s Call for White Papers for the Voyage 2050 long- term plan in the ESA Science Programme. ? Contact Scientist: Colin Wilson Atmospheric, Oceanic and Planetary Physics, Clarendon Laboratory, University of Oxford, UK. E-mail: [email protected] Venus Voyage 2050 White Paper Wilson, Widemann et al. August 2019 Executive summary In this Voyage 2050 White Paper, we emphasize the importance of a Venus exploration programme for the wider goal of understanding the diversity and evolution of habitable planets. Why are the terrestrial planets so different from each other? Venus, our nearest neighbour, should be the most Earth-like of all our planetary siblings. Its size, bulk composition and solar energy input are very similar to those of the Earth. Its original atmosphere was probably similar to that of early Earth, with large atmospheric abundances of carbon dioxide and water. Furthermore, the young sun’s fainter output may have permitted a liquid water ocean on the surface. While on Earth a moderate climate ensued, Venus experienced runaway greenhouse warming, which led to its current hostile climate. How and why did it all go wrong for Venus? What lessons can we learn about the life story of terrestrial planets/exoplanets in general, whether in our solar system or in others? Comparing the interior, surface and atmosphere evolution of Earth, Mars and Venus is essential to understanding what processes determined habitability of our own planet and Earth-like planets everywhere. -

Potential Temperature Manuel Baumgartner1,2, Ralf Weigel2, Ulrich Achatz4, Allan H

https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-2020-361 Preprint. Discussion started: 4 May 2020 c Author(s) 2020. CC BY 4.0 License. Reappraising the appropriate calculation of a common meteorological quantity: Potential Temperature Manuel Baumgartner1,2, Ralf Weigel2, Ulrich Achatz4, Allan H. Harvey3, and Peter Spichtinger2 1Zentrum für Datenverarbeitung, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Germany 2Institute for Atmospheric Physics, Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, Germany 3Applied Chemicals and Materials Division, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Boulder, CO, USA 4Institut für Atmosphäre und Umwelt, Goethe-Universität Frankfurt, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Correspondence: Manuel Baumgartner ([email protected]) Abstract. The potential temperature is a widely used quantity in atmospheric science since it is conserved for air’s adiabatic changes of state. Its definition involves the specific heat capacity of dry air, which is traditionally assumed as constant. However, the literature provides different values of this allegedly constant parameter, which are reviewed and discussed in this study. Furthermore, we derive the potential temperature for a temperature-dependent parameterization of the specific heat capacity of 5 dry air, thus providing a new reference potential temperature with a more rigorous basis. This new reference shows different values and vertical gradients in the upper troposphere and the stratosphere compared to the potential temperature that assumes constant heat capacity. The application of the new reference potential temperature to the prediction of gravity wave breaking altitudes reveals that the predicted wave breaking height may depend on the definition of the potential temperature used. 1 Introduction 10 According to the book Thermodynamics of the Atmosphere by Alfred Wegener (1911), the first published use of the expression potential temperature in meteorology is credited to Wladimir Köppen (1888)1 and Wilhelm von Bezold (1888), both following the conclusions of Hermann von Helmholtz (1888) (Kutzbach, 2016). -

The Earth's Atmosphere

The Earth’s Atmosphere Earth's atmosphere is about 300 miles (480 kilometers) thick, but most of it is within 10 miles (16 km) the surface. Air pressure decreases with altitude. At sea level, air pressure is about 14.7 pounds per square inch (1 kilogram per square centimeter). At 10,000 feet (3 km), the air pressure is 10 pounds per square inch (0.7 kg per square cm). There is also less oxygen to breathe. Composition of air The gases in Earth's atmosphere include: Nitrogen – 78 percent Oxygen – 21 percent Argon – 0.93 percent Carbon dioxide – 0.038 percent Water vapor and other gases exist in small amounts as well. Atmosphere layers Earth's atmosphere is divided into five main layers, the exosphere, the thermosphere, the mesosphere, the stratosphere and the troposphere. The atmosphere thins out in each higher layer until the gases dissipate in space. There is no distinct boundary between the atmosphere and space, but an imaginary line about 68 miles (110 kilometers) from the surface, called the Karman line, is usually where scientists say atmosphere meets outer space. • The troposphere is the layer closest to Earth's surface. It is 4 to 12 miles (7 to 20 km) thick and contains half of Earth's atmosphere. Air is warmer near the ground and gets colder higher up. Nearly all of the water vapor and dust in the atmosphere are in this layer and that is why clouds are found here. • The stratosphere is the second layer. It starts above the troposphere and ends about 31 miles (50 km) above ground.