Oregon State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Little Applegate Hydrology Report

Little Applegate Watershed Hydrology Report Michael Zan * Hydrologist April 1995 Little Applegate Watershed Analysis Hydrology Report SECTION 1 LITTLE APPLEGATE RIVER HYDROLOGY Mean Monthly Flows: Except for some data collected from May through October 1913, and from June through October 1994. there is no known flow data for the Little Applegate River or its tributaries. With this in mind it was necessary to construct a hydrograph displaying mean monthly flows by utilizing records from nearby stations that have been published in USGS Surface Water Records and Open-File Reports. In constructing a hydrograph, a short discussion of low flows is first in order. Since low streamflows have been identified as a key question pertaining to the larger issues of water quantity/quality and fish populations, the greatest need is to gain a reasonable estimate of seasonal low flows to help quantify the impacts of water withdrawals on instream beneficial uses. With this in mind, extreme caution must be used when extrapolating data from gaged to ungaged watersheds. This is particularly important in determining low-flow characteristics (Riggs 1972, Gallino 1994 personal communications). The principle terrestrial influence on low flow is geology and the primary meteorological influence is precipitation. Neither have been adequately used to describe effects on low flow using an index so that estimation of low flow characteristics of sites without discharge measurements has met with limited success. Exceptions are on streams in a region with homogeneous geology, topography, and climate, in which it should be possible to define a range of flow per square mile for a given recurrence interval. -

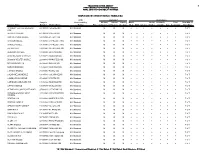

Campus Distinctions by Highest Number Met

TEXAS EDUCATION AGENCY 1 PERFORMANCE REPORTING DIVISION FINAL 2018 ACCOUNTABILITY RATINGS CAMPUS DISTINCTIONS BY HIGHEST NUMBER MET 2018 Domains* Distinctions Campus Accountability Student School Closing Read/ Social Academic Post Num Met of Campus Name Number District Name Rating Note Achievement Progress the Gaps ELA Math Science Studies Growth Gap Secondary Num Eval ACADEMY FOR TECHNOLOGY 221901010 ABILENE ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ENG ALICIA R CHACON 071905138 YSLETA ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ANN RICHARDS MIDDLE 108912045 LA JOYA ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ARAGON MIDDLE 101907051 CYPRESS-FAIRB Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 ARNOLD MIDDLE 101907041 CYPRESS-FAIRB Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 B L GRAY J H 108911041 SHARYLAND ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BENJAMIN SCHOOL 138904001 BENJAMIN ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BRIARMEADOW CHARTER 101912344 HOUSTON ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BROOKS WESTER MIDDLE 220908043 MANSFIELD ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BRYAN ADAMS H S 057905001 DALLAS ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 BURBANK MIDDLE 101912043 HOUSTON ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 C M RICE MIDDLE 043910053 PLANO ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 CALVIN NELMS MIDDLE 101837041 CALVIN NELMS Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 CAMINO REAL MIDDLE 071905051 YSLETA ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 7 of 7 CARNEGIE VANGUARD H S 101912322 HOUSTON ISD Met Standard M M M ● ● ● -

Workshop on Moon in Transition: Apollo 14, Kreep, and Evolved Lunar Rocks

WORKSHOP ON MOON IN TRANSITION: APOLLO 14, KREEP, AND EVOLVED LUNAR ROCKS (NASA-CR-I"'-- N90-I_02o rRAN31TION: APJLLN l_p KRFEP, ANu _VOLVFD LUNAR ROCKS (Lunar and Pl_net3ry !nst.) I_7 p C_CL O3B Unclas G3/91 0253133 LPI Technical Report Number 89-03 UNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE 3303 NASA ROAD 1 HOUSTON, TEXAS 77058-4399 7 WORKSHOP ON MOON IN TRANSITION: APOLLO 14, KREEP, AND EVOLVED LUNAR ROCKS Edited by G. J. Taylor and P. H. Warren Sponsored by Lunar and Planetary Institute NASA Johnson Space Center November 14-16, 1988 Houston, Texas Lunar and Planetary Institute 330 ?_NASA Road 1 Houston, Texas 77058-4399 LPI Technical Report Number 89-03 Compiled in 1989 by the LUNAR AND PLANETARY INSTITUTE The Institute is operated by Universities Space Research Association under Contract NASW-4066 with the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Material in this document may be copied without restraint for Library, abstract service, educational, or personal research purposes; however, republication of any portion requires the written permission of the authors as well as appropriate acknowledgment of this publication. This report may be cited as: Taylor G. J. and Warren PI H., eds. (1989) Workshop on Moon in Transition: Apo{l_ 14 KREEP, and Evolved Lunar Rocks. [PI Tech. Rpt. 89-03. Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. 156 pp. Papers in this report may be cited as: Author A. A. (1989) Title of paper. In W_nkshop on Moon in Transition: Ap_llo 14, KREEP, and Evolved Lunar Rocks (G. J. Taylor and P. H. Warren, eds.), pp. xx-yy. LPI Tech. Rpt. -

A Discussion of Co and 0 on Venus and Mars

, >::. X·620.,J2-209 PREPRINT ~ '. , A DISCUSSION OF CO AND 0 ON VENUS AND MARS - (NASA-T8-X-65950) A DISCUSSION OF CO AND 0 N72-28848 ON VENUS AND MARS M. Shimizu (NASA) Jun. 1972 24 p CSCL 03B Unclas G3/30 36042 MIKIO SHIMIZU JUNE 1972 -- GODDARD SPACE fLIGHT CENTER -- GREENBE~T, MARYLAND I Roproduced by NATIONAL TECHNICAL INFORMATION SERVICE us Dcparlmont 0/ Comm"rc" Springfield, VA. 22151 ~- --- -I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I A DISCUSSION OF CO AND 0 ON VENUS AND MARS by Mikio Shimizu* Laboratory for Planetary Atmospheres Goddard Space Flight Center Greenbelt, Maryland * NAS-NRC Senior Research Associate, on leave from ISAS, The University of Tokyo -I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I ABSTRACT The absorption of solar ultraviolet radiation in the wavelength o range 2000 - 2200 A by CO 2 strongly reduces the dissociation rate of HC1 on Venus. The C1 catalytic reaction for the rapid recombination of o and CO and the yellow coloration of the Venus haze by OC1 and C1 3 a~pears to be unlikely. At the time of the Martian dust storm, the dissociation of H20 in the vicinity of the surface may vanish. -

Fall 2014 New York City Campus Dean's List

DYSON COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES DEAN'S LIST NEW YORK CITY CAMPUS FALL 2014 First Honors Second Honors Third Honors Brandon Adam Cristian Abbrancati Elizabeth A. Abere Pamela Marianelli V. Agbulos Katrina Abreu Yasmine Achibat Nanichi Aguado Foy Mirandah E. Ackley Kayla R. Adens Fatima A. Ahmed Daria Afanaseva Raphael E. Ades-Aron Tiffany Amaro Salazar Yasamin Aftahi Diana D. Akelin Shabena N. Amzad Melissa Agosto Fathima Z. Alam Alexander R. Angelis Marine Alaberkian Ariana M. Alexander Shivani A. Annirood Alanoud A. Alammar Tania G. Ali Kseniya Arekhava Veronica R. Albarella Lucas M. Allen Shalynne A. Armstrong Shimma I. Almabruk Jennifer Almanzar Isabella M. Asali Rania I. Alrashoodi Michael B. Andersen Samuel W. Ashby Polina Altunina Ashley M. Aquilo Malek Assad Cody N. Alvord Alexis G. Argentine Sabeen Aziz Kerstin B. Anderson Abbey E. Ashley Stefanie C. Bacarella Alexandra L. Anschutz Marayah A. Ayoub-Schreifeldt Cara Badalamenti Savannah R. Apple Tiffany C. Babb Maria G. Baker Gabriel D. Armentano Kathryn M. Balitsos Ryan E. Barone Joshua L. Arnold Carlina S. Baptista Amani J. Basaeed Ami H. Asakawa Lucia A. Barneche Yousra Bashir Solmaz Azimi Michael A. Basil Allison E. Bass Antonina M. Bacchi Marie A. Basile Ryan C. Beaghler Michelle Back Garth O. Bates Katherine Becker Galia J. Backal Ayanna R. Bates Katherine D. Behm Connie Bahng Dahnay O. Bazunu Marilyn H. Beichner Adena E. Baichan Ashley A. Beadle Suzanne E. Beiter Matthew S. Bailey Latiana J. Blue Anastasia Beliakova Sylwia B. Baj Maria V. Borgo Adrienne R. Bengtsson Conor J. Baker Amber P. Brazil Thomas April S. Benshoshan Elisabeth Balachova Conor J. -

Florida Atlantic University

FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY Commencement Classes d196S -1969 Sunday, June 8, 1969 Two o'Clock THE CAMPUS Boca Raton, Florida !fJrogram Prelude Prelude and Fugue in C. Major- ]. S. Bach Processional Pomp and Circumstance- Edward Elgar B. Graham Ellerbee, Organist Introductions Dr. Clyde R. Burnett University Marshal Invocation The Rev. Donald Barrus United Campus Ministries National Anthem - Key- Sousa Richard Wright Instructor in Music Presiding Dr. Kenneth R. Williams President Florida Atlantic University Address "The Generation of City Builders" Dr. Robert C. Wood Director Joint Center for Urban Studies Massachusetts Institute of Technology Presentation of Baccalaureate Degrees Dr. S. E. Wimberly Vice President for Academic Affairs For the College of Business and Public Administration Dean Robert L. Froemke For the College of Education Dean Robert R. Wiegman For the College of Humanities Dean Jack Suberman For the Department of Ocean Engineering Professor Charles R. Stephan For the College of Science Dean Kenneth M. Michels For the College of Social Science Dean John M. DeGrove Presentation of the Master of Education, Master of Public Administration, Master of Science and Master of Arts Degrees Deans of the Respective Colleges Benediction The Reverend Barrus Recessional Recessional - Martin Shaw The Audience will please remain in their places until the Faculty and Graduates have left the area. 1 THE ORDER OF THE PROCE SS IO N The Marshal of the Colleges The Marshals and Candidates of the College of Business and Public Administration -

Aquatic, Wildlife, and Special Plant Habitat

I 53.2: 53A2s U.S. Department of the Interior June 1995 AQ 3/c 4 Bureau of Land Management Medford District Office 3040 Biddle 9oad Medford, Oregon 97504 I U.S. Department of Agriculture U.S. Forest Service Rogue River National Forest P.O. Box 520 _________ 333 West 8th Street Sft>TRV&> Medford, Oregon 97501 iu~s• Siskiyou National Forest ~~' ~~P.O. Box 440 Rd 200 N.E. Greenfield Rd. Grants Pass, Oregon 97526 Applegate River Watershed Assessment Aquatic, Wildlife, and Special Plant Habitat 41- As the Nation's principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interest of all our people. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in Island Territories under U.S. administration. BLWOR/WAIPL-95/031+1792 Applegate River Watershed Assessment: Aquatic, Wildlife, and Special Plant Habitat Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................... i TABLE OF FIGURES .............................................................. ii TABLE OF TABLES ............................................................. -

Snake Surveys in Jackson, Josephine and Southern Douglas Counties, Oregon

Snake Surveys in Jackson, Josephine and Southern Douglas Counties, Oregon JASON REILLY ED MEYERS DAVE CLAYTON RICHARD S. NAUMAN May 5, 2011 For more information contact: Jason Reilly Medford District Bureau of Land Management [email protected] Introduction Southwestern Oregon is recognized for its high levels of biological diversity and endemism (Whittaker 1961, Kaye et al. 1997). The warm climate and broad diversity of habitat types found in Jackson and Josephine counties result in the highest snake diversity across all of Oregon. Of the 15 snake species native to Oregon, 13 occur in the southwestern portion of the state and one species, the night snake, is potentially found here. Three of the species that occur in Oregon: the common kingsnake, the California mountain kingsnake, and the Pacific Coast aquatic garter snake are only found in southwestern Oregon (Table 1, St. John 2002). Table 1. Snakes known from or potentially found in Southwestern Oregon and conservation status. Scientific Name Common Name Special Status Category1 Notes Charina bottae Rubber Boa None Common Sharp-tailed See Feldman and Contia tenuis None Snake Hoyer 2010 Recently described Forest Sharp-tailed Contia longicaudae None species see Feldman Snake and Hoyer 2010 Diadophis Ring-necked Snake None punctatus Coluber constrictor Racer None Masticophis Appears to be very Stripped Whipsnake None taeniatus rare in SW Oregon Pituophis catenifer Gopher Snake None Heritage Rank G5/S3 Lampropeltis Federal SOC Appears to be rare in Common Kingsnake getula ODFW SV SW Oregon ORBIC 4 Heritage Rank G4G5/S3S4 Lampropeltis California Mountain Federal SOC zonata Kingsnake ODFW SV ORBIC 4 Thamnophis sirtalis Common Garter Snake None Thamnophis Northwestern Garter None ordinoides Snake Thamnophis Western Terrestrial None elegans Garter Snake Thamnophis Pacific Coast Aquatic None atratus Garter Snake No records from SW Hypsiglena Oregon. -

Rogue River Date: March 11, 1938 Work Plan Nth Period Camp Applgbate F-41 Name and Number /S/ Karl L

ccc SUMMARY COPY Camp Program Forest: Rogue River Date: March 11, 1938 Work Plan nth Period Camp ApplgBate F-41 Name and Number /s/ Karl L. Janouch forest Supervisor Total Man Months Work From: Material Little Apple. Costs Main Camp Side CamD Side Camo Side Camp Truck Trail Construction & Maintenance 340 185 6.150 Hor3<j Trail Construction 6 Maintenance 60 800 Administrative Improvements 48 450 Protective Improvements 132 975 Fire Prevention, Pre.Sup.5 Fire Suppression Hazard- Reduction Projects Range Management Projects 143 670 '<,'ild Life Projects Erosion Control Projects Recreation Projects 106 370 Insect Control & Timber Management Projects Experimental Forest Projects TOTALS 829 185 $9,514 Total amount of material costs as shown on work Dlans that cannot be financed from camo allotments Name Location No. Men Durat ion (. Months) Littlfi ApplPgatff S.rr.?fi,T39S. R2W .35. 4/1-9/30. JL. Side Camps ccc Plans Camp Programs Forest: Rogue River Work Plan 11th Period Camp Applegate F-41 Name and Number Date: March 11, 1933 Sheet 1 of 2 sheets Karl L. Janowch Forest Supervisor Star (*) material items that cannot be financed from current camp allotments. : Map : : Material : Start : Coi:io"leTe rSurober: lion Months l*ork : No. : Units : Costs : Date : Date : of Men: t'ain "C'-ciipfSi'de ~Cp. Truck Trail Construction Star Gulch 192 3 2,000 4/1 9/30 40 240 Tallowbox L.O. 399 200 5/1 6/30 20 40 Little Applegate 395 i& 2,000 Vi 9/30- 30 180 Goat Cabin Ridge 389 w, 200 5/1 5/31 5 5 Truck Trail Maintenance 165 1,650 4/20 6/20 20 40 Bridge Maintenance 1 1 100 20 Trnil Maintenance 400 800 4/1 6/30 20 60 Telephone Line Betterment 2 25 5/1 5/31 7 7 Water Development (Springs) 1-3 3 95 8/1 8/31 5 3 Silver Fork Soil Erosion contours 20 50 Mi. -

Klamath Mountains Ecoregion

Ecoregions: Klamath Mountains Ecoregion Photo © Bruce Newhouse Klamath Mountains Ecoregion Getting to Know the Klamath Mountains Ecoregion example, there are more kinds of cone-bearing trees found in the Klam- ath Mountains ecoregion than anywhere else in North America. In all, The Oregon portion of the Klamath Mountains ecoregion covers much there are about 4000 native plants in Oregon, and about half of these of southwestern Oregon, including the Umpqua Mountains, Siskiyou are found in the Klamath Mountains ecoregion. The ecoregion is noted Mountains and interior valleys and foothills between these and the as an Area of Global Botanical Significance (one of only seven in North Cascade Range. Several popular and scenic rivers run through the America) and world “Centre of Plant Diversity” by the World Conserva- ecoregion, including: the Umpqua, Rogue, Illinois, and Applegate. tion Union. The ecoregion boasts many unique invertebrates, although Within the ecoregion, there are wide ranges in elevation, topography, many of these are not as well studied as their plant counterparts. geology, and climate. The elevation ranges from about 600 to more than 7400 feet, from steep mountains and canyons to gentle foothills and flat valley bottoms. This variation along with the varied marine influence support a climate that ranges from the lush, rainy western portion of the ecoregion to the dry, warmer interior valleys and cold snowy mountains. Unlike other parts of Oregon, the landscape of the Klamath Mountains ecoregion has not been significantly shaped by volcanism. The geology of the Klamath Mountains can better be described as a mosaic rather than the layer-cake geology of most of the rest of the state. -

Evaluation of Streamflow Records in Rogue River Basin, Oregon

GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 187 \ EVALUATION OF STREAMFLOW RECORDS IN ROGUE RIVER BASIN, OREGON B!y Donald Rkhaideon UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Oscar L. Chapman, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CIRCULAR 187 EVALUATION OF STREAMFLOW RECORDS IN ROGUE RIVER BASIN, OREGON By Donald Richardson Washington, D. C., 1952 Free on application to the Geological Surrey, Washington 25, D. C. ' CONTENTS Page Page Abstract................................. 1 Syllabus of gaging-stations records--Con. Introduction............................. 1 Gaging-station records-Continued Purpose and Scope...................... 1 Rogue River Continued Acknowledgments........................ 1 Little Butte Creek at Lake Creek... 25 Physical features- of the basin........... 2 Little Butte Creek above Eagle Utilization of water in the basin........ 2 Point............................ 25 Water resources data for Rogue River basin 5 Little Butte Creek near Eagle Streamflow records ..................... 5 Point............................ 25 Storage reservoirs..................... 6 Little Butte Creek below Eagle Adequacy of data....................... 6 Point............................ 26 Syllabus of gaging-station records....... 13 Emigrant Creek (head of Bear Creek) Explanation of data .................... 13 near Ashland..................... 27 Gaging-station records................. 13 Emigrant Creek below Walker Creek, Rogue River above Bybee Creek........ 13 near Ashland..................... 28 Rogue River above -

Venus Mesosphere and Thermosphere II. Global Circulation

ICARUS 68, 284--312 (1986) Venus Mesosphere and Thermosphere II. Global Circulation, Temperature, and Density Variations S. W. BOUGHER,*'t R. E. DICKINSON,$ E. C. RIDLEY,§ R. G. ROBLE,* A. F. NAGY, II AND T. E. CRAVENS II *High Altitude Observatory, ~fAdvanced Study Program, $Atmospheric Analysis and Prediction, and §Scientific Computing Division, National Center for Atmospheric Research, I P.O. Box 3000, Boulder, Colorado 80307; and IISpace Physics Research Laboratory, 2455 Hayward, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109 Received February 13, 1986; revised July 11, 1986 Recent Pioneer Venus observations have prompted a return to comprehensive hydrodynamical modeling of the thermosphere of Venus. Our approach has been to reexamine the circulation and structure of the thermosphere using the framework of the R. E. Dickinson and E. C. Ridley (1977, Icarus 30, 163-178), symmetric two-dimensional model. Sensitivity tests were conducted to see how large-scale winds, eddy diffusion and conduction, and strong 15-/xm cooling affect day-night contrasts of densities and temperatures. The calculated densities and temperatures are compared to symmetric empirical model fields constructed from the Pioneer Venus data base. We find that the observed day-to-night variation of composition and temperatures can be derived largely by a wave- drag parameterization that gives a circulation system weaker than predicted prior to Pioneer Venus. The calculated mesospheric winds are consistent with Earth-based observations near 115 km. Our studies also suggest that eddy diffusion is only a minor contributor to the maintenance of observed day and nightside densities, and that eddy coefficients are smaller than values used by previous one-dimensional composition models.