Contents/Sommaire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Communism and Post-Communism in Romania : Challenges to Democratic Transition

TITLE : COMMUNISM AND POST-COMMUNISM IN ROMANIA : CHALLENGES TO DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION AUTHOR : VLADIMIR TISMANEANU, University of Marylan d THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FO R EURASIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE VIII PROGRA M 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D .C . 20036 LEGAL NOTICE The Government of the District of Columbia has certified an amendment of th e Articles of Incorporation of the National Council for Soviet and East European Research changing the name of the Corporation to THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR EURASIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH, effective on June 9, 1997. Grants, contracts and all other legal engagements of and with the Corporation made unde r its former name are unaffected and remain in force unless/until modified in writin g by the parties thereto . PROJECT INFORMATION : 1 CONTRACTOR : University of Marylan d PR1NCIPAL 1NVEST1GATOR : Vladimir Tismanean u COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 81 1-2 3 DATE : March 26, 1998 COPYRIGHT INFORMATIO N Individual researchers retain the copyright on their work products derived from research funded by contract with the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research . However, the Council and the United States Government have the right to duplicate an d disseminate, in written and electronic form, this Report submitted to the Council under thi s Contract, as follows : Such dissemination may be made by the Council solely (a) for its ow n internal use, and (b) to the United States Government (1) for its own internal use ; (2) for further dissemination to domestic, international and foreign governments, entities an d individuals to serve official United States Government purposes ; and (3) for dissemination i n accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of the United State s Government granting the public rights of access to documents held by the United State s Government. -

Between Denial and "Comparative Trivialization": Holocaust Negationism in Post-Communist East Central Europe

Between Denial and "Comparative Trivialization": Holocaust Negationism in Post-Communist East Central Europe Michael Shafir Motto: They used to pour millet on graves or poppy seeds To feed the dead who would come disguised as birds. I put this book here for you, who once lived So that you should visit us no more Czeslaw Milosz Introduction* Holocaust denial in post-Communist East Central Europe is a fact. And, like most facts, its shades are many. Sometimes, denial comes in explicit forms – visible and universally-aggressive. At other times, however, it is implicit rather than explicit, particularistic rather than universal, defensive rather than aggressive. And between these two poles, the spectrum is large enough to allow for a large variety of forms, some of which may escape the eye of all but the most versatile connoisseurs of country-specific history, culture, or immediate political environment. In other words, Holocaust denial in the region ranges from sheer emulation of negationism elsewhere in the world to regional-specific forms of collective defense of national "historic memory" and to merely banal, indeed sometime cynical, attempts at the utilitarian exploitation of an immediate political context.1 The paradox of Holocaust negation in East Central Europe is that, alas, this is neither "good" nor "bad" for the Jews.2 But it is an important part of the * I would like to acknowledge the support of the J. and O. Winter Fund of the Graduate Center of the City University of New York for research conducted in connection with this project. I am indebted to friends and colleagues who read manuscripts of earlier versions and provided comments and corrections. -

Absurdistan Refacut Cu Headere Ultimul.P65

Dorin Tudoran (n. 30 iunie 1945, Timi[oara). Absolvent al Facult\]ii de Limb\ [i Literatur\ Român\ a Universit\]ii din Bucure[ti, pro- mo]ia 1968. Este Senior Director, pentru Comunicare [i Cercetare, membru al conducerii executive a Funda]iei Interna]ionale IFES, Washington D.C., Statele Unite, [i redactor-[ef al revistei democracy at large. C\r]i de poezie: Mic tratat de glorie (1973), C`ntec de trecut Akheronul (1975), O zi `n natur\ (1977), Uneori, plutirea (1977), Respira]ie artificial\ (1978), Pasaj de pietoni (1978), Semne particulare (antologie, 1979), De bun\ voie, autobiografia mea (1986), Ultimul turnir (antologie, 1992), Optional Future (1988), Viitorul Facultativ/Optional Future (1999), T`n\rul Ulise (antologie, 2000). C\r]i de publicistic\: Martori oculari (`n colaborare cu Eugen Seceleanu, 1976), Biografia debuturilor (1978), Nostalgii intacte (1982), Adaptarea la realitate (1982), Frost or Fear? On the Condition of the Romanian Intelectual (traducere [i prefa]\ de Vladimir Tism\neanu, 1988), Onoarea de a `n]elege (antologie, 1998), Kakistokra]ia (1998). Pentru unele dintre c\r]ile sale, autorul a primit Premiul Uniunii Scriitorilor (1973, 1977, 1998), Marele Premiu al Asocia]iilor Scriitorilor Profesioni[ti ASPRO (1998), Premiul Uniunii Scriitorilor din Republica Moldova (1998), Premiul revistei Cuv`ntul Superlativele anului (1998). I s-a decernat un Premiu Special al Uniunii Scriitorilor (1992) [i este laureatul Premiului ALA pe anul 2001. www.polirom.ro © 2006 by Editura POLIROM Editura POLIROM Ia[i, B-dul Carol I nr. 4, P.O. BOX 266, 700506 Bucure[ti, B-dul I.C. Br\tianu nr. 6, et. -

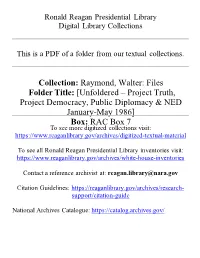

Unfoldered – Project Truth, Project Democracy, Public Diplomacy

Ronald Reagan Presidential Library Digital Library Collections This is a PDF of a folder from our textual collections. Collection: Raymond, Walter: Files Folder Title: [Unfoldered – Project Truth, Project Democracy, Public Diplomacy & NED January-May 1986] Box: RAC Box 7 To see more digitized collections visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/digitized-textual-material To see all Ronald Reagan Presidential Library inventories visit: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/white-house-inventories Contact a reference archivist at: [email protected] Citation Guidelines: https://reaganlibrary.gov/archives/research- support/citation-guide National Archives Catalogue: https://catalog.archives.gov/ WITHDRAWAL SHEET Ronald Reagan Library Collection Name RAYMOND, w ALTER: FILES Withdrawer SMF 7/14/2011 File Folder [PROJECT TRUTH, PROJECT DEMOCRACY, PUBLIC FOIA DIPLOMACY, AND NED JANUARY 1986-MAY 1986] M430 Box Number 7 LAMB, CHRISTOPHER 72 ID DocType Document Description Noof Doc Date Restrictions 115205 MEMO REICHLER TO ACTIVE MEASURES 5 2/25/1986 Bl B3 WORKING GROUP RE ACTIVE MEASURES MEMO #3 OF 1986 p 11/21/2002 F95-041/2 #78; PAR M430/1 #115205 3/31/2015 115206 MINUTES ACTIVE MEASURES WORKING GROUP 4 2/27/1986 Bl B3 2/27 /86 MEETING p 11/21/2002 F95-041/2 #78; PAR M430/1 B6 #115206 3/31/2015 115208 NOTE SITUATION ROOM RE SOVIET 1 2/25/1986 Bl PROPAGANDA EFFORTS D 7/19/2000 F95-041/2 #80; PAR M430/1 #115208 3/31/2015 115211 CABLE 150045Z FEB 86 3 2/15/1986 Bl B3 D 7/3/2000 F95-041/2 #81; UPHELD M430/2 #115211 3/31/2015 115213 MINUTES ACTIVE MEASURES WORKING GROUP 3 5/27/1986 Bl B3 5/22/86 MEETING p 11/21/2002 F95-041/2 #82; PAR M430/1 B6 #115213 3/31/2015 Freedom of Information Act - (5 U.S.C. -

Christian Church8

www.ssoar.info From periphery to centre: the image of Europe at the Eastern Border of Europe Şipoş, Sorin (Ed.); Moisa, Gabriel (Ed.); Cepraga, Dan Octavian (Ed.); Brie, Mircea (Ed.); Mateoc, Teodor (Ed.) Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Konferenzband / collection Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Şipoş, S., Moisa, G., Cepraga, D. O., Brie, M., & Mateoc, T. (Eds.). (2014). From periphery to centre: the image of Europe at the Eastern Border of Europe. Cluj-Napoca: Ed. Acad. Română. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168- ssoar-400284 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY Lizenz (Namensnennung) zur This document is made available under a CC BY Licence Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden (Attribution). For more Information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de Edited by: Sorin §ipo§, Gabriel Moisa, Dan Octavian Cepraga, Mircea Brie, Teodor Mateoc From Periphery to Centre. The Image of Europe at the Eastern Border of Europe Editorial committee: Delia-Maria Radu Roxana Iva^ca Alexandra Bere IonuJ Ciorba Romanian Academy Center for Transylvanian Studies Cluj-Napoca 2014 Descrierea CIP a Bibliotecii Nationale a României From periphery to centre : the image of Europe at the Eastern border of Europe/ Sorin Çipoç, Gabriel Moisa, Dan Octavian Cepraga, Mircea Brie (ed.). - Cluj-Napoca : Editura Academia Românâ. Centrul de Studii Transilvane, 2014 ISBN 978-973-7784-97-1 I. Çipoç, Sorin (ed.) II. Moisa, Gabriel (ed.) III. Cepraga, Dan Octavian (ed.) IV. Brie, Mircea (ed.) 930 Volume published with the support of Bihor County Council The volume gathers the papers presented at the international symposium From Periphery to Centre. -

Lucian Pintilie and Censorship in a Post-Stalinist Authoritarian Context

Psychology, 2019, 10, 1159-1175 http://www.scirp.org/journal/psych ISSN Online: 2152-7199 ISSN Print: 2152-7180 Lucian Pintilie and Censorship in a Post-Stalinist Authoritarian Context Emanuel-Alexandru Vasiliu Apollonia TV, Iași, Romania How to cite this paper: Vasiliu, E.-A. Abstract (2019). Lucian Pintilie and Censorship in a Post-Stalinist Authoritarian Context. Psy- The objective of my work is to shed light on the way in which the post-1953 chology, 10, 1159-1175. ideology of the Romanian Communist Party influenced Romanian theatre https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2019.108075 and film director Lucian Pintilie’s career, resulting in a ban to work in Roma- Received: May 21, 2019 nia. Reacting to the imposition of the cultural revolution and against the laws Accepted: June 27, 2019 of coagulating the socialist realist work of art, Lucian Pintilie managed to Published: June 30, 2019 mark the Romanian theatrical and cinema landscape through the artistic quality of the productions and the directed films, replicated by the renown of Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and Scientific Research Publishing Inc. the imposed interdiction. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International Keywords License (CC BY 4.0). http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Lucian Pintilie, Censorship, Ideology, Theatre Open Access 1. General Presentation Ceauşescu’s Romania was a closed society, characterised by repression in all fields of human existence: limitations of ownerships rights, hard labour condi- tions and small wages, lacking freedom of movement, bureaucratic obstacles against emigration, violations of the rights of national minorities, contempt for religious faiths and the persecution of religious practices, drastic economic aus- terity, constant censorship in the field of culture, the repression of all dissident views and an omnipresent cult around the president and his family, which con- tributed to the demoralisation of the population. -

GEO) Conference

Global Electoral Organization (GEO) Conference March 27-29, 2007 FINAL REPORT Global Electoral Organization (GEO) Conference Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Executive Summary…………………………………………………………….….2 II. Objectives and Outcomes………………………………………………..……...3 III. Conclusions……………………………………………………………………….….11 IV. Annexes a. Presentations…………….…………………………………………………....12 b. List of Participants ……………………………………………….………….16 c. Meeting Minutes………..……………………………………………..……..24 d. Conference Program.………………………………………………………..40 e. Photographs…………….……………………………………………………...42 1 Global Electoral Organization (GEO) Conference March 27-29, 2007 – Washington, DC EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Among the many challenges confronting democratic nations, ensuring citizens’ right to free, fair and transparent elections ranks especially high. In election commissions around the world, talented and committed professionals often find themselves with limited access to a network of peers they can consult for professional advice. The conferences of the Global Electoral Organization (GEO) regularly provide senior election officials and democracy practitioners a much needed opportunity to gather together in person and share common experiences and find solutions to issues in election management. IFES, an international nonprofit organization that supports the building of democratic societies, hosted the fourth gathering of the GEO network at the Westin Grand in Washington, D.C., from March 27–29, 2007. This year’s GEO conference also received support from 11 other leading international and government organizations and the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA). Attendees at this year’s GEO conference included more than 250 international electoral systems experts, representatives from national and regional electoral management bodies, universities, and the diplomatic and donor communities from over 50 countries. This final report highlights the extent to which the 2007 GEO Conference met various conference objectives set by the host, IFES. -

Resistance Through Literature in Romania (1945-1989)

DePaul University Via Sapientiae College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences 11-2015 Resistance through literature in Romania (1945-1989) Olimpia I. Tudor Depaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd Recommended Citation Tudor, Olimpia I., "Resistance through literature in Romania (1945-1989)" (2015). College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations. 199. https://via.library.depaul.edu/etd/199 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Liberal Arts & Social Sciences Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Resistance through Literature in Romania (1945-1989) A Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts October, 2015 BY Olimpia I. Tudor Department of International Studies College of Liberal Arts and Social Sciences DePaul University Chicago, Illinois Acknowledgements I am sincerely grateful to my thesis adviser, Dr. Shailja Sharma, PhD, for her endless patience and support during the development of this research. I wish to thank her for kindness and generosity in sharing her immense knowledge with me. Without her unconditional support, this thesis would not have been completed. Besides my adviser, I would like to extend my gratitude to Dr. Nila Ginger Hofman, PhD, and Professor Ted Anton who kindly agreed to be part of this project, encouraged and offered me different perspectives that helped me find my own way. -

LITERATURE Iulian Boldea, Dumitru-Mircea Buda, Cornel Sigmirean

Iulian Boldea, Dumitru-Mircea Buda, Cornel Sigmirean (Editors) MEDIATING GLOBALIZATION: Identities in Dialogue Arhipelag XXI Press, 2018 THE FORCEFUL CONVERSION OF THE THEATRE PEOPLE DURING THE COMMUNISM Centa-Mariana Artagea (Solomon) PhD Student, ”Dun ărea de Jos” University of Gala ți Abstract: The post revolutionary literary histories talk about the radicalism of communism, about the various answers of the Romanian intellectuals, from the outrageous faction to the optimistic collaboration. However, it is fascinating to analyze authentic documents in which to discover the relations between the people of the regime and literati, especially on limited temporal units and specific events. The press after 1947 has monitored and influenced cultural life, as did the Theater magazine, whose articles from the first years of founding (1956-1960) offer us the opportunity to discover the insoluble dialogue between the two worlds, political and literary. The dramaturgy at that time appears to us, subjected to the drama of forcing itself into the only artistic pattern validated by the political authority that had to echo like an ovation. Keywords: dramaturgy, communism, conversion, press, monitoring In 1956, June 18-23, the Communists besieged the Romanian literature, wishing to boldly condemn the official passage from the rules formulated in the press after "liberation" to the new “list of laws” announced at the first Congress of Writers of the Romanian People's Republic, in Bucharest, as we learn from the Theater magazine, the June issue of the same year. Because "the literary press is the first and most faithful mirror of the degradation of literary life" 1, the analysis of this journal, insisting on the year of the first Congress of Writers and its echoes in the sixth decade, will give us data on customized conversion to the new ideological directions of thespians, with aesthetic implications. -

FINAL REPORT International Commission on the Holocaust In

FINAL REPORT of the International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania Presented to Romanian President Ion Iliescu November 11, 2004 Bucharest, Romania NOTE: The English text of this Report is currently in preparation for publication. © International Commission on the Holocaust in Romania. All rights reserved. DISTORTION, NEGATIONISM, AND MINIMALIZATION OF THE HOLOCAUST IN POSTWAR ROMANIA Introduction This chapter reviews and analyzes the different forms of Holocaust distortion, denial, and minimalization in post-World War II Romania. It must be emphasized from the start that the analysis is based on the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s definition of the Holocaust, which Commission members accepted as authoritative soon after the Commission was established. This definition1 does not leave room for doubt about the state-organized participation of Romania in the genocide against the Jews, since during the Second World War, Romania was among those allies and a collaborators of Nazi Germany that had a systematic plan for the persecution and annihilation of the Jewish population living on territories under their unmitigated control. In Romania’s specific case, an additional “target-population” subjected to or destined for genocide was the Romany minority. This chapter will employ an adequate conceptualization, using both updated recent studies on the Holocaust in general and new interpretations concerning this genocide in particular. Insofar as the employed conceptualization is concerned, two terminological clarifications are in order. First, “distortion” refers to attempts to use historical research on the dimensions and significance of the Holocaust either to diminish its significance or to serve political and propagandistic purposes. Although its use is not strictly confined to the Communist era, the term “distortion” is generally employed in reference to that period, during which historical research was completely subjected to controls by the Communist Party’s political censorship. -

Intellectuals and Public Discourse

Intellectuals and Public Discourse: Talking about Literature in Socialist Romania By Mihai-Dan Cîrjan Submitted to Central European University History Department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Constantin Iordachi Second Reader: Professor Balázs Trencsényi CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2011 Copyright in the text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies by any process, either in full or part, may be made only in accordance with the instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European Library. Details may be obtained from the librarian. This page must form a part of any such copies made. Further copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the written permission of the Author. CEU eTD Collection i Abstract This thesis is a contribution to the study of intellectuals under state socialism. It aims to analyse the structure of the Romanian literary field during and after the liberalisation period of the 1960s. It does this by following the trajectory of two Romanian writers inside the institutional and discursive structures of the literary field. The two case studies provide the opportunity to discuss the effects of the state’s institutionalisation of culture. The thesis claims that the co-option of the intelligentsia in the administrative system and the structure of informal networks developed within the state’s institutions made the literary field a complex site where members of the intelligentsia and of the bureaucratic elite engaged in multiple negotiations for state resources. In this scenario the boundaries between the two elites, far from being clear cut, constantly shifted within the confines of state administration. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES-Thursday, January 25, 1990 the House Met at 11 A.M

January 25, 1990 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 495 HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES-Thursday, January 25, 1990 The House met at 11 a.m. Scenic Rivers System, and for other pur DO NOT FORGET COAL MINERS The Chaplain, Rev. James David poses; and IN CLEAN AIR DEBATE S. 1594. An act to revise the boundary of Ford, D.D., offered the following <Mr. POSHARD asked and was given prayer: Gettysburg National Military Park in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and for permission to address the House for 1 Teach us, 0 God, a unity of purpose other purposes. minute and to revise and extend his that brings us together to do the good remarks and include extraneous work that we have been called to do. matter.) We admit our differences, our preju DENVER BRONCOS ARE GOING Mr. POSHARD. Mr. Speaker, this dices, and we pray for the gifts of the TO WIN THE SUPER BOWL year starts on a very down note for me spirit that free us to live lives that are and my district in southern Illinois. worthy of our responsibility. Bless the <Mrs. SCHROEDER asked and was given permission to address the House Here is the headline in the Southern men and women here and the people Illinoisan newspaper: "Old Ben 21 of our land, unite the nations of the for 1 minute and to revise and extend world and every person of good will in her remarks.) Closes; 337 Left Jobless," 337 hard an attitude of common respect. May Mrs. SCHROEDER. Mr. Speaker, working men and women whose lives we be faithful to do Your good will the Denver Broncos are going to win are being turned upside-down.