THE TON-MILE: DOES IT PROPERLY MEASURE TRANSPORTATION OUTPUT? Allan C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standard Conversion Factors

Standard conversion factors 7 1 tonne of oil equivalent (toe) = 10 kilocalories = 396.83 therms = 41.868 GJ = 11,630 kWh 1 therm = 100,000 British thermal units (Btu) The following prefixes are used for multiples of joules, watts and watt hours: kilo (k) = 1,000 or 103 mega (M) = 1,000,000 or 106 giga (G) = 1,000,000,000 or 109 tera (T) = 1,000,000,000,000 or 1012 peta (P) = 1,000,000,000,000,000 or 1015 WEIGHT 1 kilogramme (kg) = 2.2046 pounds (lb) VOLUME 1 cubic metre (cu m) = 35.31 cu ft 1 pound (lb) = 0.4536 kg 1 cubic foot (cu ft) = 0.02832 cu m 1 tonne (t) = 1,000 kg 1 litre = 0.22 Imperial = 0.9842 long ton gallon (UK gal.) = 1.102 short ton (sh tn) 1 UK gallon = 8 UK pints 1 Statute or long ton = 2,240 lb = 1.201 U.S. gallons (US gal) = 1.016 t = 4.54609 litres = 1.120 sh tn 1 barrel = 159.0 litres = 34.97 UK gal = 42 US gal LENGTH 1 mile = 1.6093 kilometres 1 kilometre (km) = 0.62137 miles TEMPERATURE 1 scale degree Celsius (C) = 1.8 scale degrees Fahrenheit (F) For conversion of temperatures: °C = 5/9 (°F - 32); °F = 9/5 °C + 32 Average conversion factors for petroleum Imperial Litres Imperial Litres gallons per gallons per per tonne tonne per tonne tonne Crude oil: Gas/diesel oil: Indigenous Gas oil 257 1,167 Imported Marine diesel oil 253 1,150 Average of refining throughput Fuel oil: Ethane All grades 222 1,021 Propane Light fuel oil: Butane 1% or less sulphur 1,071 Naphtha (l.d.f.) >1% sulphur 232 1,071 Medium fuel oil: Aviation gasoline 1% or less sulphur 237 1,079 >1% sulphur 1,028 Motor -

Conversion Factors for SI and Non-SI Units

Conversion Factors for SI and non-SI Units To convert Column 1 To convert Column 2 into Column 2, into Column 1, multiply by Column 1 SI Unit Column 2 non-SI Units multiply by Length 0.621 kilometer, km (103 m) mile, mi 1.609 1.094 meter, m yard, yd 0.914 3.28 meter, m foot, ft 0.304 6 1.0 micrometer, mm (10- m) micron, m 1.0 3.94 × 10-2 millimeter, mm (10-3 m) inch, in 25.4 10 nanometer, nm (10-9 m) Angstrom, Å 0.1 Area 2.47 hectare, ha acre 0.405 247 square kilometer, km2 (103 m)2 acre 4.05 × 10-3 0.386 square kilometer, km2 (103 m)2 square mile, mi2 2.590 2.47 × 10-4 square meter, m2 acre 4.05 × 103 10.76 square meter, m2 square foot, ft2 9.29 × 10-2 1.55 × 10-3 square millimeter, mm2 (10-3 m)2 square inch, in2 645 Volume 9.73 × 10-3 cubic meter, m3 acre-inch 102.8 35.3 cubic meter, m3 cubic foot, ft3 2.83 × 10-2 6.10 × 104 cubic meter, m3 cubic inch, in3 1.64 × 10-5 2.84 × 10-2 liter, L (10-3 m3) bushel, bu 35.24 1.057 liter, L (10-3 m3) quart (liquid), qt 0.946 3.53 × 10-2 liter, L (10-3 m3) cubic foot, ft3 28.3 0.265 liter, L (10-3 m3) gallon 3.78 33.78 liter, L (10-3 m3) ounce (fluid), oz 2.96 × 10-2 2.11 liter, L (10-3 m3) pint (fluid), pt 0.473 Mass 2.20 × 10-3 gram, g (10-3 kg) pound, lb 454 3.52 × 10-2 gram, g (10-3 kg) ounce (avdp), oz 28.4 2.205 kilogram, kg pound, lb 0.454 0.01 kilogram, kg quintal (metric), q 100 1.10 × 10-3 kilogram, kg ton (2000 lb), ton 907 1.102 megagram, Mg (tonne) ton (U.S.), ton 0.907 1.102 tonne, t ton (U.S.), ton 0.907 Yield and Rate 0.893 kilogram per hectare, kg ha-1 pound per acre, lb acre-1 -

Useful Conversions

Useful Conversions Agronomic: · 1 acre-foot of soil = 2,000 tons (approximate @ 92 lbs/cu. ft.) · 1 lb per acre = 0.0104 grams per square foot · 100 lbs per acre = 0.2296 lbs per 100 square foot · 1 cubic feet per second = 448.8 gallons per minute · 1 lb = 16 ounces = 454 grams · 1 oz = 28.375 grams · 1 inch = 2.54 cm · 1 gallon = 3.78 liters · 1 ppm = 2 lbs/acre of soil 6" deep @ 92 lbs/cu. ft. · 1 ton per acre = 20.8 g per sq. ft. = 0.73 ounces/ sq. ft. · 1 ton per acre = 1 lb per 21.78 sq. ft. · 1 ton per acre = 4.59 lb per 100 sq. ft. · 1 gram per sq. ft. = 96 lbs per acre · 1 lb per acre = 1.12 kilograms per hectare · 1 lb per acre = 0.01042 grams per sq. ft. · 1 ton per acre = 1 kg per 48 sq. ft. · lbs per sq. ft. x 21.768 = tons per acre · lbs per sq. ft. x 43,560 = lbs per acre · 1 acre = 0.405 hectares · 1 mile = 1.61 km · parts per million (ppm) x 0.00136 = tons per acre-foot To convert a soil test from ppm to lbs per acre. 1. Determine the depth of soil in inches that the soil represents 2. Divide this depth by 3 3. Multiply the result by the soil test result Example: Soil test for nitrate is 9 ppm and sampled depth is 12” (12”/3 = 4, 4 x 9 = 36 lb/ac) Mathematics Chart: Multiply by To obtain Acres 43,560 Sq. -

The International System of Units (SI) - Conversion Factors For

NIST Special Publication 1038 The International System of Units (SI) – Conversion Factors for General Use Kenneth Butcher Linda Crown Elizabeth J. Gentry Weights and Measures Division Technology Services NIST Special Publication 1038 The International System of Units (SI) - Conversion Factors for General Use Editors: Kenneth S. Butcher Linda D. Crown Elizabeth J. Gentry Weights and Measures Division Carol Hockert, Chief Weights and Measures Division Technology Services National Institute of Standards and Technology May 2006 U.S. Department of Commerce Carlo M. Gutierrez, Secretary Technology Administration Robert Cresanti, Under Secretary of Commerce for Technology National Institute of Standards and Technology William Jeffrey, Director Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document in order to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by the National Institute of Standards and Technology, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose. National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publications 1038 Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Pub. 1038, 24 pages (May 2006) Available through NIST Weights and Measures Division STOP 2600 Gaithersburg, MD 20899-2600 Phone: (301) 975-4004 — Fax: (301) 926-0647 Internet: www.nist.gov/owm or www.nist.gov/metric TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD.................................................................................................................................................................v -

Energy Basics Bioresources Biofuels Petroleum Biomass Energy

Energy Basics BioResources BioFuels Petroleum Biomass Energy Cord Wood: Stack of wood comprising 128 cubic feet (3.62 m3) Standard dimensions are 4 x 4 x 8 feet includes air space and bark One cord contains approx. 1.2 U.S. tons (oven-dry) = 2400 pounds = 1089 kg 1.0 metric tonne wood = 1.4 cubic meters (solid wood, not stacked) Energy content of wood fuel (HHV, bone dry) = 18-22 GJ/t (7,600-9,600 Btu/lb) Energy content of wood fuel (air dry, 20% moisture) ≅ 15 GJ/t (6,400 Btu/lb) Energy content of agricultural residues (varying moisture content) = 10-17 GJ/t (4,300-7,300 Btu/lb) Metric tonne charcoal = 30 GJ = 12,800 Btu/lb Ethanol – Biodiesel Energy Metric tonne ethanol = 7.94 petroleum barrels = 1262 liters LHV Ethanol energy content = 11,500 Btu/lb = 75,700 Btu/gallon = 26.7 GJ/t = 21.1 MJ/liter. HHV for ethanol = 84,000 Btu/gallon = 89 MJ/gallon = 23.4 MJ/liter Average ethanol density (average) = 0.79 g/ml Average metric tonne biodiesel = 37.8 GJ typically 33.3 - 35.7 MJ/liter Average biodiesel density = 0.88 g/ml Areas and Crop Yields 1.0 hectare = 10,000 m2 = 328 x 328 ft = 2.47 acres 1.0 km2 = 100 hectares = 247 acres 1.0 acre = 0.405 hectares 1.0 US ton/acre = 2.24 t/ha 1 metric tonne/hectare = 0.446 ton/acre 100 g/m2 = 1.0 tonne/hectare = 892 lb/acre Target bioenergy crop yield might be: 5.0 US tons/acre (10,000 lb/acre) = 11.2 tonnes/hectare (1120 g/m2) 1.0 US Bushel corn/sorgum = 56 lb, 25 kg 1.0 US Bushel wheat/soybeans= 60 lb, 27 kg (wheat or soybeans) 1.0 US Bushell barley = 40 lb, 18 kg (barley) Fossil Fuel Energy Barrel of oil equivalent (boe) ≅ 6.1 GJ (5.8 million Btu), equivalent to 1,700 kWh. -

Handout – Unit Conversions (Dimensional Analysis)

1 Handout – Unit Conversions (Dimensional Analysis) The Metric System had its beginnings back in 1670 by a mathematician called Gabriel Mouton. The modern version, (since 1960) is correctly called "International System of Units" or "SI" (from the French "Système International"). The metric system has been officially sanctioned for use in the United States since 1866, but it remains the only industrialized country that has not adopted the metric system as its official system of measurement. Many sources also cite Liberia and Burma as the only other countries not to have done so. This section will cover conversions (1) selected units Basic metric units in the metric and American systems, (2) compound or derived measures, and (3) between metric and length meter (m) American systems. Also, (4) applications using conversions will be presented. mass gram (g) The metric system is based on a set of basic units and volume liter (L) prefixes representing powers of 10. time second (s) temperature Celsius (°C) or Kelvin (°K) where C=K-273.15 Prefixes (The units that are in bold are the ones that are most commonly used.) prefix symbol value giga G 1,000,000,000 = 109 ( a billion) mega M 1,000,000 = 106 ( a million) kilo k 1,000 = 103 hecto h 100 = 102 deca da 10 1 1 -1 deci d = 0.1 = 10 10 1 -2 centi c = 0.01 = 10 100 1 -3 milli m = 0.001 = 10 (a thousandth) 1,000 1 -6 micro μ (the Greek letter mu) = 0.000001 = 10 (a millionth) 1,000,000 1 -9 nano n = 0.000000001 = 10 (a billionth) 1,000,000,000 2 To get a sense of the size of the basic units of meter, gram and liter consider the following examples. -

Units of Measure Used in International Trade Page 1/57 Annex II (Informative) Units of Measure: Code Elements Listed by Name

Annex II (Informative) Units of Measure: Code elements listed by name The table column titled “Level/Category” identifies the normative or informative relevance of the unit: level 1 – normative = SI normative units, standard and commonly used multiples level 2 – normative equivalent = SI normative equivalent units (UK, US, etc.) and commonly used multiples level 3 – informative = Units of count and other units of measure (invariably with no comprehensive conversion factor to SI) The code elements for units of packaging are specified in UN/ECE Recommendation No. 21 (Codes for types of cargo, packages and packaging materials). See note at the end of this Annex). ST Name Level/ Representation symbol Conversion factor to SI Common Description Category Code D 15 °C calorie 2 cal₁₅ 4,185 5 J A1 + 8-part cloud cover 3.9 A59 A unit of count defining the number of eighth-parts as a measure of the celestial dome cloud coverage. | access line 3.5 AL A unit of count defining the number of telephone access lines. acre 2 acre 4 046,856 m² ACR + active unit 3.9 E25 A unit of count defining the number of active units within a substance. + activity 3.2 ACT A unit of count defining the number of activities (activity: a unit of work or action). X actual ton 3.1 26 | additional minute 3.5 AH A unit of time defining the number of minutes in addition to the referenced minutes. | air dry metric ton 3.1 MD A unit of count defining the number of metric tons of a product, disregarding the water content of the product. -

Unit Conversions

Unit Conversions EQUIVALENCY UNIT CONVERSION FACTOR Length 1 foot = 12 inches ____1 ft or ____12 in 12 in 1 ft 1 yd ____3 ft 1 yard = 3 feet ____ or 3 ft 1 yd 1 mile = 5280 feet ______1 mile or ______5280 ft 5280 ft 1 mile Time 1 min 60 sec 1 minute = 60 seconds ______ or ______ 60 sec 1 min 1 hr 60 min 1 hour = 60 minutes ______ or ______ 60 min 1 hr 1 day 24 hr 1 day = 24 hours ______ or ______ 24 hr 1 day ______1 week ______7 days 1 week = 7 days or 7 days 1 week Volume (Capacity) 1 cup = 8 fluid ounces ______1 cup or ______8 fl oz 8 fl oz 1 cup 1 pt 2 cups 1 pint = 2 cups ______ or ______ 2 cups 1 pt ______1 qt 1 quart = 2 pints or ______2 pts 2 pts 1 qt ______1 gal ______4 qts 1 gallon = 4 quarts or 4 qts 1 gal Weight 1 pound = 16 ounces ______1 lb or ______16 oz 16 oz 1 lb 1 ton 2000 lbs 1 ton = 2000 pounds _______ or _______ 2000 lbs 1 ton How to Make a Unit Conversion STEP1: Select a unit conversion factor. Which unit conversion factor we use depends on the units we start with and the units we want to end up with. units we want Numerator Unit conversion factor: units to eliminate Denominator For example, if we want to convert minutes into seconds, we want to eliminate minutes and end up with seconds. Therefore, we would use 60 sec . -

9Th Grade | Unit 10

SCIENCE STUDENT BOOK 9th Grade | Unit 10 804 N. 2nd Ave. E. Rock Rapids, IA 51246-1759 800-622-3070 www.aop.com Unit 10 | Science Review SCIENCE 910 Science Review INTRODUCTION |3 1. PRACTICAL USES OF MEASUREMENT 5 THE METRIC SYSTEM |5 WEIGHT VERSUS MASS |7 SELF TEST 1 |11 2. PRACTICAL HEALTH 13 TRAVELING ABROAD |14 CAMPING AND HIKING |19 KEEPING PERSONAL HEALTH RECORDS |21 SELF TEST 2 |25 3. PRACTICAL GEOLOGY AND ASTRONOMY 27 UPBUILDING VERSUS EROSION |27 THE OCEANS |30 THE CONTINENTS |32 PLATE TECTONICS |35 SELF TEST 3 |38 4. PRACTICAL SOLUTIONS TO PROBLEMS 41 NUCLEAR POWER |41 POPULATION |46 ENVIRONMENT |47 SELF TEST 4 |50 LIFEPAC Test is located in the center of the booklet. Please remove before starting the unit. Section 1 |1 Science Review | Unit 10 Author: Darnelle Dunn, M.S. Editor-In-Chief: Richard W. Wheeler, M.A.Ed. Editor: Mary L. Meyer Consulting Editor: Harold Wengert, Ed.D. Revision Editor: Alan Christopherson, M.S. Westover Studios Design Team: Phillip Pettet, Creative Lead Teresa Davis, DTP Lead Nick Castro Andi Graham Jerry Wingo Don Lechner 804 N. 2nd Ave. E. Rock Rapids, IA 51246-1759 © MCMXCVI by Alpha Omega Publications, Inc. All rights reserved. LIFEPAC is a registered trademark of Alpha Omega Publications, Inc. All trademarks and/or service marks referenced in this material are the property of their respective owners. Alpha Omega Publications, Inc. makes no claim of ownership to any trademarks and/ or service marks other than their own and their affiliates, and makes no claim of affiliation to any companies whose trademarks may be listed in this material, other than their own. -

Conversion Chart Revised

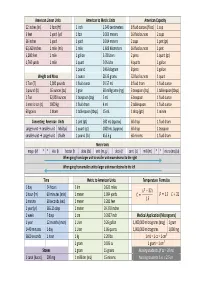

American Linear Units American to Metric Units American Capacity 12 inches (in) 1 foot (ft) 1 inch 2.540 centimeters 8 fluid ounces (fl oz) 1 cup 3 feet 1 yard (yd) 1 foot 0.305 meters 16 fluid ounces 2 cups 36 inches 1 yard 1 yard 0.914 meters 2 cups 1 pint (pt) 63,360 inches 1 mile (mi) 1 mile 1.609 kilometers 16 fluid ounces 1 pint 5,280 feet 1 mile 1 gallon 3.78 Liters 2 pints 1 quart (qt) 1,760 yards 1 mile 1 quart 0.95 Liter 4 quarts 1 gallon 1 pound 0.45 kilogram 8 pints 1 gallon Weight and Mass 1 ounce 28.35 grams 32 fluid ounces 1 quart 1 T on (T) 2,000 pounds 1 fluid ounce 29.57 mL 8 fluid dram 1 fluid ounce 1 pound (lb) 16 ounces (oz) 1 grain 60 milligrams (mg) 3 teaspoon (tsp) 1 tablespoon (tbsp) 1 Ton 32,000 ounces 1 teaspoon (tsp) 5 mL 6 teaspoon 1 fluid ounce 1 metric ton (t) 1000 kg 1 fluid dram 4 mL 2 tablespoon 1 fluid ounce 60 grains 1 dram 1 tablespoon (tbsp) 15 mL 1 drop (gtt) 1 minim Converting American Units 1 pint (pt) 500 mL (approx) 60 drop 1 fluid dram Larger unit → smaller unit Multiply 1 quart (qt) 1000 mL (approx) 60 drop 1 teaspoon smaller unit → Larger unit Divide 1 pound (lb) 453.6 g 60 minims 1 fluid dram Metric Units mega (M) * * kilo (k) hector (h) deka (da) unit (m, g, L) deci (d) centi (c) milli (m) * * micro (mc) (u) When going from larger unit to smaller unit move decimal to the right cimal to the left When going from smaller unit to larger unit move de Time Metric to American Units Temperature Formulas 1 day 24 hours 1 km 0.621 miles ʚ̀ Ǝ 32 ʛ 1 hour (hr) 60 minutes (min) 1 meter 1.094 yards ̽ -

Telegram Open Network (TON)

Telegram Open Network Dr. Nikolai Durov March 2, 2019 Abstract The aim of this text is to provide a first description of the Tele- gram Open Network (TON) and related blockchain, peer-to-peer, dis- tributed storage and service hosting technologies. To reduce the size of this document to reasonable proportions, we focus mainly on the unique and defining features of the TON platform that are important for it to achieve its stated goals. Introduction The Telegram Open Network (TON) is a fast, secure and scalable blockchain and network project, capable of handling millions of transactions per second if necessary, and both user-friendly and service provider-friendly. We aim for it to be able to host all reasonable applications currently proposed and conceived. One might think about TON as a huge distributed supercom- puter, or rather a huge “superserver”, intended to host and provide a variety of services. This text is not intended to be the ultimate reference with respect to all implementation details. Some particulars are likely to change during the development and testing phases. 1 Introduction Contents 1 Brief Description of TON Components 3 2 TON Blockchain 5 2.1 TON Blockchain as a Collection of 2-Blockchains . 5 2.2 Generalities on Blockchains . 15 2.3 Blockchain State, Accounts and Hashmaps . 19 2.4 Messages Between Shardchains . 29 2.5 Global Shardchain State. “Bag of Cells” Philosophy. 38 2.6 Creating and Validating New Blocks . 44 2.7 Splitting and Merging Shardchains . 57 2.8 Classification of Blockchain Projects . 61 2.9 Comparison to Other Blockchain Projects . -

Appendix B – Units and Systems of Measurement

Handbook 44 – 2011 Appendix B – Units and Systems of Measurement Table of Contents Appendix B. Units and Systems of Measurement Their Origin, Development, and Present Status .................................................................................................... B3 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... B3 2. Units and Systems of Measurement ............................................................................................................. B3 2.1. Origin and Early History of Units and Standards. ............................................................................... B3 2.1.1. General Survey of Early History of Measurement Systems. ................................................. B3 2.1.2. Origin and Development of Some Common Customary Units. ............................................ B4 2.2. The Metric System. .............................................................................................................................. B5 2.2.1. Definition, Origin, and Development. ................................................................................... B5 2.2.2. International System of Units. ............................................................................................... B6 2.2.3. Units and Standards of the Metric System. ........................................................................... B6 2.3. British and United States Systems of Measurement.