Craniosynostosis HAIDAR KABBANI, M.D., and TALKAD S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Guidelines Review Evidence on PT, Helmets for Positional Plagiocephaly by Sandi K

Neurologic Disorders, Neurological Surgery, News Articles New guidelines review evidence on PT, helmets for positional plagiocephaly by Sandi K. Lam M.D., M.B.A., FACS; Thomas G. Luerssen M.D., FACS, FAAP Positional plagiocephaly is a common condition encountered by pediatricians and referred to pediatric subspecialty physicians such as neurosurgeons and plastic surgeons. About one in four U.S. infants has some degree of positional plagiocephaly. The incidence has increased since the Academy initiated the Back to Sleep campaign in 1994 to prevent sudden infant death syndrome. Due to practice variation in diagnosis and treatment paradigms for this common condition, the Joint Section on Pediatric Neurosurgery of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons (CNS) sought to develop evidence-based management guidelines. A multidisciplinary task force conducted a systematic review of the literature from 1966 to October 2014 on pediatric plagiocephaly. Nearly 400 abstracts were reviewed yielding 110 articles for full review; 60 were deemed relevant. The task force made 10 recommendations pertaining to imaging diagnosis, repositioning, physical therapy and helmet orthoses. The guidelines are published in CNS' journal Neurosurgery and have been endorsed by the Academy. They are available at http://bit.ly/2d7NzS1. Definition of positional plagiocephaly In the guidelines, the term positional plagiocephaly encompasses both positional occipital plagiocephaly (unilateral flattening of parieto-occipital region, compensatory anterior shift of the ipsilateral ear, bulging of the ipsilateral forehead) and positional brachycephaly (symmetric flattening of the occiput, foreshortened anterior- posterior dimension of the skull, compensatory biparietal widening) and the combination of both of these deformities. -

Pfeiffer Syndrome Type II Discovered Perinatally

Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging (2012) 93, 785—789 CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector LETTER / Musculoskeletal imaging Pfeiffer syndrome type II discovered perinatally: Report of an observation and review of the literature a,∗ a a a H. Ben Hamouda , Y. Tlili , S. Ghanmi , H. Soua , b c b a S. Jerbi , M.M. Souissi , H. Hamza , M.T. Sfar a Unité de néonatologie, service de pédiatrie, CHU Tahar Sfar, 5111 Mahdia, Tunisia b Service de radiologie, CHU Tahar Sfar, 5111 Mahdia, Tunisia c Service de gynéco-obstétrique, CHU Tahar Sfar, 5111 Mahdia, Tunisia Pfeiffer syndrome, described for the first time by Pfeiffer in 1964, is a rare hereditary KEYWORDS condition combining osteochondrodysplasia with craniosynostosis [1]. This syndrome is Pfeiffer syndrome; also called acrocephalosyndactyly type 5, which is divided into three sub-types. Type I Cloverleaf skull; is the classic Pfeiffer syndrome, with autosomal dominant transmission, often associated Craniosynostosis; with normal intelligence. Types II and III occur as sporadic cases in individuals who have Syndactyly; craniosynostosis with broad thumbs, broad big toes, ankylosis of the elbows and visceral Prenatal diagnosis abnormalities [2]. We report a case of Pfeiffer syndrome type II, discovered perinatally, which is distinguished from type III by the skull appearing like a cloverleaf, and we shall discuss the clinical, radiological and evolutive features and the advantage of prenatal diagnosis of this syndrome with a review of the literature. Observation The case involved a male premature baby born at 36 weeks of amenorrhoea with multiple deformities at birth. The parents were not blood-related and in good health who had two other boys and a girl with normal morphology. -

Coronal and Lambdoid Suture Evolution Following Total Vault Remodeling for Scaphocephaly

NEUROSURGICAL FOCUS Neurosurg Focus 50 (4):E4, 2021 Coronal and lambdoid suture evolution following total vault remodeling for scaphocephaly Pierre-Aurélien Beuriat, MD, PhD,1,2,4 Alexandru Szathmari, MD, PhD,1,2 Julie Chauvel-Picard, MD,1,3,4 Arnaud Gleizal, MD, PhD,1,3,4 Christian Paulus, MD,1,3 Carmine Mottolese, MD, PhD,1,2 and Federico Di Rocco, MD, PhD1,2,4 1French Referral Center for Craniosynostosis; Departments of 2Pediatric Neurosurgery and 3Pediatric Maxillo-Facial Surgery, Hôpital Femme Mère Enfant; and 4Université de Lyon, France OBJECTIVE Different types of surgical procedures are utilized to treat craniosynostosis. In most procedures, the fused suture is removed. There are only a few reports on the evolution of sutures after surgical correction of craniosynostosis. To date, no published study describes neosuture formation after total cranial vault remodeling. The objective of this study was to understand the evolution of the cranial bones in the area of coronal and lambdoid sutures that were removed for complete vault remodeling in patients with sagittal craniosynostosis. In particular, the investigation aimed to confirm the possibility of neosuture formation. METHODS CT images of the skulls of children who underwent operations for scaphocephaly at the Hôpital Femme Mère Enfant, Lyon University Hospital, Lyon, France, from 2004 to 2014 were retrospectively reviewed. Inclusion crite- ria were diagnosis of isolated sagittal synostosis, age between 4 and 18 months at surgery, and availability of reliable postoperative CT images obtained at a minimum of 1 year after surgical correction. Twenty-six boys and 11 girls were included, with a mean age at surgery of 231.6 days (range 126–449 days). -

Frontosphenoidal Synostosis: a Rare Cause of Unilateral Anterior Plagiocephaly

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Childs Nerv Syst (2007) 23:1431–1438 DOI 10.1007/s00381-007-0469-4 ORIGINAL PAPER Frontosphenoidal synostosis: a rare cause of unilateral anterior plagiocephaly Sandrine de Ribaupierre & Alain Czorny & Brigitte Pittet & Bertrand Jacques & Benedict Rilliet Received: 30 March 2007 /Published online: 22 September 2007 # Springer-Verlag 2007 Abstract Conclusion Frontosphenoidal synostosis must be searched Introduction When a child walks in the clinic with a in the absence of a coronal synostosis in a child with unilateral frontal flattening, it is usually associated in our anterior unilateral plagiocephaly, and treated surgically. minds with unilateral coronal synostosis. While the latter might be the most common cause of anterior plagiocephaly, Keywords Craniosynostosis . Pediatric neurosurgery. it is not the only one. A patent coronal suture will force us Anterior plagiocephaly to consider other etiologies, such as deformational plagio- cephaly, or synostosis of another suture. To understand the mechanisms underlying this malformation, the development Introduction and growth of the skull base must be considered. Materials and methods There have been few reports in the Harmonious cranial growth is dependent on patent sutures, literature of isolated frontosphenoidal suture fusion, and and any craniosynostosis might lead to an asymmetrical we would like to report a series of five cases, as the shape of the skull. The anterior skull base is formed of recognition of this entity is important for its treatment. different bones, connected by sutures, fusing at different ages. The frontosphenoidal suture extends from the end of Presented at the Consensus Conference on Pediatric Neurosurgery, the frontoparietal suture, anteriorly and inferiorly in the Rome, 1–2 December 2006. -

Cleidocranial Dysplasia- a Case Report

Case Report Cleidocranial Dysplasia- A Case Report Akhilanand Chaurasia Department of Oral Medicine & Radiology, Faculty of Dental Sciences, King George Medical University, Lucknow E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Cleidocranial dysplasia is a rare congenital disease. It is characterized by autosomal dominant inheritance pattern which is caused due to mutations in the Cbfa1 gene (Runx2) located on chromosome 6p21. It primarily affects bones which are formedby intra-membranous ossification and have equal sex distribution. It is also known as Marie and Sainton disease, Mutational dysostosis and cleidocranialdysostosis. The skeletal deformities of cleidocranial dysplasia are characterized by partial or complete absence of clavicles, late closure of the fontanels, presence of open skull sutures and multiple wormian bones. This rare syndrome is of utmost importance in dentistry due to presence of multiple supernumerary teeth, facial bones deformities and deranged eruption patterns. We are reporting a classical case of cleidocranial dysplasia in 20 year old patient. Keywords: Cleidocranial dysplasia, Marie and Sainton disease, Mutational dysostosis, Cleidocranialdysostosis, Autosomal dominant Access this article online mandibular symphysis are less common findings of Quick Response cleidocranial dysostosis1,10,11. Code: Website: Dental findings in cleidocranialdysostosis are www.innovativepublication.com characterized by a decreased eruptive force of both primary and permanent dentition, prolonged retention of primary teeth12 and an increase in odontogenesis DOI: 10.5958/2395-6194.2015.00009.0 leading to an excessive number of supernumerary teeth13. The clinical findings of cleidocranialdysostosis although present at birth are often either missed or INTRODUCTION diagnosed at a much later time. Cleidocranialdysostosis Cleidocranialdysostosis is a rare congenital defect may be identified by family history, excessive mobility primarily affecting bones which undergo intra- of shoulders and radiographic pathognomonic findings membranous ossification i.e. -

Comparison of the Newborn Skull to the Adult Human Skull

Comparison of the Newborn skull to the Adult Human Skull As a baby grows older their skull goes through a huge change. The neurocranium starts off not as hard as it will be, gaining the ability to shape in whatever way is needed. While their facial cranium, their face, begins to take on unique qualities and changes to look like a mature adult skull. This process takes time but all the changes are very visible. The neurocranium compared to an adult’s is more oval and is substantially bigger than the facial cranium. The newborn's skull has four “horns” two in the front on the frontal bone and two in the back on the parietal bone. These bumps are the thickness that the skull will eventually become. The edges are ridged in between the frontal and the parietal. On top of the skull is the anterior fontanel, which is an opening in the skull that is small and shaped like a diamond. This will close when the child is around two years old. Coming out of the points from the anterior fontanelle are lines or spaces in between the bones, some of these overlap. The advantage of both the spaces in between the bones and the anterior fontanel is room for growth and compression through the birth canal. As a newborn, their neurocranium is 60% of the circumference of an adult’s. At two to three it is 90% of an adult’s, so most of the growth of the neurocranium happens before the child is three. The adult’s skull is more circular and the nose, eyes, and mouth are father apart. -

Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly

277 Megalencephaly and Macrocephaly KellenD.Winden,MD,PhD1 Christopher J. Yuskaitis, MD, PhD1 Annapurna Poduri, MD, MPH2 1 Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, Address for correspondence Annapurna Poduri, Epilepsy Genetics Massachusetts Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Electrophysiology, 2 Epilepsy Genetics Program, Division of Epilepsy and Clinical Department of Neurology, Fegan 9, Boston Children’s Hospital, 300 Electrophysiology, Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115 Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts (e-mail: [email protected]). Semin Neurol 2015;35:277–287. Abstract Megalencephaly is a developmental disorder characterized by brain overgrowth secondary to increased size and/or numbers of neurons and glia. These disorders can be divided into metabolic and developmental categories based on their molecular etiologies. Metabolic megalencephalies are mostly caused by genetic defects in cellular metabolism, whereas developmental megalencephalies have recently been shown to be caused by alterations in signaling pathways that regulate neuronal replication, growth, and migration. These disorders often lead to epilepsy, developmental disabilities, and Keywords behavioral problems; specific disorders have associations with overgrowth or abnor- ► megalencephaly malities in other tissues. The molecular underpinnings of many of these disorders are ► hemimegalencephaly now understood, providing insight into how dysregulation of critical pathways leads to ► -

The Genetic Heterogeneity of Brachydactyly Type A1: Identifying the Molecular Pathways

The genetic heterogeneity of brachydactyly type A1: Identifying the molecular pathways Lemuel Jean Racacho Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in Biochemistry Specialization in Human and Molecular Genetics Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology Faculty of Medicine University of Ottawa © Lemuel Jean Racacho, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 Abstract Brachydactyly type A1 (BDA1) is a rare autosomal dominant trait characterized by the shortening of the middle phalanges of digits 2-5 and of the proximal phalange of digit 1 in both hands and feet. Many of the brachymesophalangies including BDA1 have been associated with genetic perturbations along the BMP-SMAD signaling pathway. The goal of this thesis is to identify the molecular pathways that are associated with the BDA1 phenotype through the genetic assessment of BDA1-affected families. We identified four missense mutations that are clustered with other reported BDA1 mutations in the central region of the N-terminal signaling peptide of IHH. We also identified a missense mutation in GDF5 cosegregating with a semi-dominant form of BDA1. In two families we reported two novel BDA1-associated sequence variants in BMPR1B, the gene which codes for the receptor of GDF5. In 2002, we reported a BDA1 trait linked to chromosome 5p13.3 in a Canadian kindred (BDA1B; MIM %607004) but we did not discover a BDA1-causal variant in any of the protein coding genes within the 2.8 Mb critical region. To provide a higher sensitivity of detection, we performed a targeted enrichment of the BDA1B locus followed by high-throughput sequencing. -

Crouzon Syndrome with Ophthalmological Complications

Journal of Rawalpindi Medical College (JRMC); 2012;16(1):80-81 Case Report Crouzon Syndrome With Ophthalmological Complications Rahela Nasir Paediatric Department, Capital Hospital, CDA Islamabad. Crouzon Syndrome is characterized by premature bilateral optic atrophy. Other facial features included a craniosynostosis. It has an autosomal dominant inheritance prominent nose and deep and narrow palate. No but represents fresh mutation also. Other craniofacial digital abnormalities were seen. No dental aplasia was abnormalities include ocular proptosis caused by shallow present. Systemic examination revealed no orbits with or without divergent strabismus. There may be abnormality. increased intracranial pressure for which surgical morcellation procedures are indicated. A case of He was diagnosed as a case of Crouzon syndrome craniosynostosis is reported which is diagnosed as Crouzon with ocular complications on clinical basis. He was Syndrome with ocular complications on clinical grounds. investigated for microcephaly and suspected Split craniotomy was performed by a neurosurgeon to craniosynostosis. Radiographs of skull showed small relieve raised intracranial pressure and to enhance brain sized skull with early closure of sutures and fontanelle growth. Crouzon Syndrome was originally described in 1912 suggestive of craniosynstosis(Fig 2). A hammered- by Crouzon in a mother and her daughter. It is an autosomal silver (beaten metal/ copper beaten) appearance was dominant inherited disorder but represents fresh mutation also seen due to raised intracranial pressure and also. Crouzon syndrome is characterized by premature compression of the developing brain on the fused craniosynostosis which is quite variable but the coronal suture is nearly always bilaterally involved. Craniofacial bone. CT scan brain with contrast was done which abnormalities include brachycephaly, shallow orbits and confirmed the features suggestive of craniosynostosis maxillary hypoplasia. -

Genetics of Congenital Hand Anomalies

G. C. Schwabe1 S. Mundlos2 Genetics of Congenital Hand Anomalies Die Genetik angeborener Handfehlbildungen Original Article Abstract Zusammenfassung Congenital limb malformations exhibit a wide spectrum of phe- Angeborene Handfehlbildungen sind durch ein breites Spektrum notypic manifestations and may occur as an isolated malforma- an phänotypischen Manifestationen gekennzeichnet. Sie treten tion and as part of a syndrome. They are individually rare, but als isolierte Malformation oder als Teil verschiedener Syndrome due to their overall frequency and severity they are of clinical auf. Die einzelnen Formen kongenitaler Handfehlbildungen sind relevance. In recent years, increasing knowledge of the molecu- selten, besitzen aber aufgrund ihrer Häufigkeit insgesamt und lar basis of embryonic development has significantly enhanced der hohen Belastung für Betroffene erhebliche klinische Rele- our understanding of congenital limb malformations. In addi- vanz. Die fortschreitende Erkenntnis über die molekularen Me- tion, genetic studies have revealed the molecular basis of an in- chanismen der Embryonalentwicklung haben in den letzten Jah- creasing number of conditions with primary or secondary limb ren wesentlich dazu beigetragen, die genetischen Ursachen kon- involvement. The molecular findings have led to a regrouping of genitaler Malformationen besser zu verstehen. Der hohe Grad an malformations in genetic terms. However, the establishment of phänotypischer Variabilität kongenitaler Handfehlbildungen er- precise genotype-phenotype correlations for limb malforma- schwert jedoch eine Etablierung präziser Genotyp-Phänotyp- tions is difficult due to the high degree of phenotypic variability. Korrelationen. In diesem Übersichtsartikel präsentieren wir das We present an overview of congenital limb malformations based Spektrum kongenitaler Malformationen, basierend auf einer ent- 85 on an anatomic and genetic concept reflecting recent molecular wicklungsbiologischen, anatomischen und genetischen Klassifi- and developmental insights. -

Craniosynostosis and Related Disorders Mark S

CLINICAL REPORT Guidance for the Clinician in Rendering Pediatric Care Identifying the Misshapen Head: Craniosynostosis and Related Disorders Mark S. Dias, MD, FAAP, FAANS,a Thomas Samson, MD, FAAP,b Elias B. Rizk, MD, FAAP, FAANS,a Lance S. Governale, MD, FAAP, FAANS,c Joan T. Richtsmeier, PhD,d SECTION ON NEUROLOGIC SURGERY, SECTION ON PLASTIC AND RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY Pediatric care providers, pediatricians, pediatric subspecialty physicians, and abstract other health care providers should be able to recognize children with abnormal head shapes that occur as a result of both synostotic and aSection of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Department of Neurosurgery and deformational processes. The purpose of this clinical report is to review the bDivision of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, College of characteristic head shape changes, as well as secondary craniofacial Medicine and dDepartment of Anthropology, College of the Liberal Arts characteristics, that occur in the setting of the various primary and Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, Pennsylvania State University, State College, Pennsylvania; and cLillian S. Wells Department of craniosynostoses and deformations. As an introduction, the physiology and Neurosurgery, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, genetics of skull growth as well as the pathophysiology underlying Florida craniosynostosis are reviewed. This is followed by a description of each type of Clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefit from primary craniosynostosis (metopic, unicoronal, bicoronal, sagittal, lambdoid, expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external reviewers. However, clinical reports from the American Academy of and frontosphenoidal) and their resultant head shape changes, with an Pediatrics may not reflect the views of the liaisons or the emphasis on differentiating conditions that require surgical correction from organizations or government agencies that they represent. -

Morfofunctional Structure of the Skull

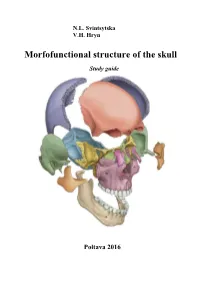

N.L. Svintsytska V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine Public Institution «Central Methodological Office for Higher Medical Education of MPH of Ukraine» Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukranian Medical Stomatological Academy» N.L. Svintsytska, V.H. Hryn Morfofunctional structure of the skull Study guide Poltava 2016 2 LBC 28.706 UDC 611.714/716 S 24 «Recommended by the Ministry of Health of Ukraine as textbook for English- speaking students of higher educational institutions of the MPH of Ukraine» (minutes of the meeting of the Commission for the organization of training and methodical literature for the persons enrolled in higher medical (pharmaceutical) educational establishments of postgraduate education MPH of Ukraine, from 02.06.2016 №2). Letter of the MPH of Ukraine of 11.07.2016 № 08.01-30/17321 Composed by: N.L. Svintsytska, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor V.H. Hryn, Associate Professor at the Department of Human Anatomy of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Ukrainian Medical Stomatological Academy», PhD in Medicine, Associate Professor This textbook is intended for undergraduate, postgraduate students and continuing education of health care professionals in a variety of clinical disciplines (medicine, pediatrics, dentistry) as it includes the basic concepts of human anatomy of the skull in adults and newborns. Rewiewed by: O.M. Slobodian, Head of the Department of Anatomy, Topographic Anatomy and Operative Surgery of Higher State Educational Establishment of Ukraine «Bukovinian State Medical University», Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor M.V.