A Review of the Management of Single-Suture Craniosynostosis, Past, Present, and Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Genetic Heterogeneity of Brachydactyly Type A1: Identifying the Molecular Pathways

The genetic heterogeneity of brachydactyly type A1: Identifying the molecular pathways Lemuel Jean Racacho Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctorate in Philosophy degree in Biochemistry Specialization in Human and Molecular Genetics Department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology Faculty of Medicine University of Ottawa © Lemuel Jean Racacho, Ottawa, Canada, 2015 Abstract Brachydactyly type A1 (BDA1) is a rare autosomal dominant trait characterized by the shortening of the middle phalanges of digits 2-5 and of the proximal phalange of digit 1 in both hands and feet. Many of the brachymesophalangies including BDA1 have been associated with genetic perturbations along the BMP-SMAD signaling pathway. The goal of this thesis is to identify the molecular pathways that are associated with the BDA1 phenotype through the genetic assessment of BDA1-affected families. We identified four missense mutations that are clustered with other reported BDA1 mutations in the central region of the N-terminal signaling peptide of IHH. We also identified a missense mutation in GDF5 cosegregating with a semi-dominant form of BDA1. In two families we reported two novel BDA1-associated sequence variants in BMPR1B, the gene which codes for the receptor of GDF5. In 2002, we reported a BDA1 trait linked to chromosome 5p13.3 in a Canadian kindred (BDA1B; MIM %607004) but we did not discover a BDA1-causal variant in any of the protein coding genes within the 2.8 Mb critical region. To provide a higher sensitivity of detection, we performed a targeted enrichment of the BDA1B locus followed by high-throughput sequencing. -

Genetics of Congenital Hand Anomalies

G. C. Schwabe1 S. Mundlos2 Genetics of Congenital Hand Anomalies Die Genetik angeborener Handfehlbildungen Original Article Abstract Zusammenfassung Congenital limb malformations exhibit a wide spectrum of phe- Angeborene Handfehlbildungen sind durch ein breites Spektrum notypic manifestations and may occur as an isolated malforma- an phänotypischen Manifestationen gekennzeichnet. Sie treten tion and as part of a syndrome. They are individually rare, but als isolierte Malformation oder als Teil verschiedener Syndrome due to their overall frequency and severity they are of clinical auf. Die einzelnen Formen kongenitaler Handfehlbildungen sind relevance. In recent years, increasing knowledge of the molecu- selten, besitzen aber aufgrund ihrer Häufigkeit insgesamt und lar basis of embryonic development has significantly enhanced der hohen Belastung für Betroffene erhebliche klinische Rele- our understanding of congenital limb malformations. In addi- vanz. Die fortschreitende Erkenntnis über die molekularen Me- tion, genetic studies have revealed the molecular basis of an in- chanismen der Embryonalentwicklung haben in den letzten Jah- creasing number of conditions with primary or secondary limb ren wesentlich dazu beigetragen, die genetischen Ursachen kon- involvement. The molecular findings have led to a regrouping of genitaler Malformationen besser zu verstehen. Der hohe Grad an malformations in genetic terms. However, the establishment of phänotypischer Variabilität kongenitaler Handfehlbildungen er- precise genotype-phenotype correlations for limb malforma- schwert jedoch eine Etablierung präziser Genotyp-Phänotyp- tions is difficult due to the high degree of phenotypic variability. Korrelationen. In diesem Übersichtsartikel präsentieren wir das We present an overview of congenital limb malformations based Spektrum kongenitaler Malformationen, basierend auf einer ent- 85 on an anatomic and genetic concept reflecting recent molecular wicklungsbiologischen, anatomischen und genetischen Klassifi- and developmental insights. -

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases Biomed Central

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases BioMed Central Review Open Access Brachydactyly Samia A Temtamy* and Mona S Aglan Address: Department of Clinical Genetics, Human Genetics and Genome Research Division, National Research Centre (NRC), El-Buhouth St., Dokki, 12311, Cairo, Egypt Email: Samia A Temtamy* - [email protected]; Mona S Aglan - [email protected] * Corresponding author Published: 13 June 2008 Received: 4 April 2008 Accepted: 13 June 2008 Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2008, 3:15 doi:10.1186/1750-1172-3-15 This article is available from: http://www.ojrd.com/content/3/1/15 © 2008 Temtamy and Aglan; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Abstract Brachydactyly ("short digits") is a general term that refers to disproportionately short fingers and toes, and forms part of the group of limb malformations characterized by bone dysostosis. The various types of isolated brachydactyly are rare, except for types A3 and D. Brachydactyly can occur either as an isolated malformation or as a part of a complex malformation syndrome. To date, many different forms of brachydactyly have been identified. Some forms also result in short stature. In isolated brachydactyly, subtle changes elsewhere may be present. Brachydactyly may also be accompanied by other hand malformations, such as syndactyly, polydactyly, reduction defects, or symphalangism. For the majority of isolated brachydactylies and some syndromic forms of brachydactyly, the causative gene defect has been identified. -

MR Imaging of Fetal Head and Neck Anomalies

Neuroimag Clin N Am 14 (2004) 273–291 MR imaging of fetal head and neck anomalies Caroline D. Robson, MB, ChBa,b,*, Carol E. Barnewolt, MDa,c aDepartment of Radiology, Children’s Hospital Boston, 300 Longwood Avenue, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115, USA bMagnetic Resonance Imaging, Advanced Fetal Care Center, Children’s Hospital Boston, Harvard Medical School, 300 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA cFetal Imaging, Advanced Fetal Care Center, Children’s Hospital Boston, Harvard Medical School, 300 Longwood Avenue, Boston, MA 02115, USA Fetal dysmorphism can occur as a result of var- primarily used for fetal MR imaging. When the fetal ious processes that include malformation (anoma- face is imaged, the sagittal view permits assessment lous formation of tissue), deformation (unusual of the frontal and nasal bones, hard palate, tongue, forces on normal tissue), disruption (breakdown of and mandible. Abnormalities include abnormal promi- normal tissue), and dysplasia (abnormal organiza- nence of the frontal bone (frontal bossing) and lack of tion of tissue). the usual frontal prominence. Abnormal nasal mor- An approach to fetal diagnosis and counseling of phology includes variations in the size and shape of the parents incorporates a detailed assessment of fam- the nose. Macroglossia and micrognathia are also best ily history, maternal health, and serum screening, re- diagnosed on sagittal images. sults of amniotic fluid analysis for karyotype and Coronal images are useful for evaluating the in- other parameters, and thorough imaging of the fetus tegrity of the fetal lips and palate and provide as- with sonography and sometimes fetal MR imaging. sessment of the eyes, nose, and ears. -

Flat Foot II

726 S.-A. MEDIESE TYDSKRIF 3 Julie 1971 ligament below with interrupted black silk sutures. The sutures located at the most medial part also passed through the outer edge of the rectus sheath. The internal ring was reconstituted so that it was situated lateral to the external ring to ensure that the obliquity of the inguinal canal was maintained (Fig. I). In 1890, Bassini reported his experience with 262 con secutive cases who had had a hernia repaired according to the new method he described. Out of 251 cases where strangulation had not occurred, all survived the operation. The recurrence rate was less than 3% of those cases who had been followed up for between one month and four years. The operation described by Bassini has made a great impact on the surgery of inguinal herniae, and although many different procedures have been described, none has had a similar world-wide acceptance. The Bassini opera tion has withstood the test of time, and proof of its value lies in the fact that it is still used today by many surgeons in different parts of the globe. Fig. 1: Bassini's original description of herniorrhaphy. I wish to thank Professor J. M. Mynors and Mrs P. Ferguson (A) subcutaneous tissue, (B) external oblique, (C) fascia for assistance in preparing this paper, and Mr G. Davie, for transversalis, (E) spermatic cord, (F) transversus, internal the photograph. oblique and fascia transversus, (G) hernia sac. (From Bassini's (j ber die Behandlung des Leisten-bruches, REFERENCES Langenbecks Arch. klin. Chir., Vo\. 40.) 1. Celsus, 1st Century, AD (1938): De Medicine. -

Four Unusual Cases of Congenital Forelimb Malformations in Dogs

animals Article Four Unusual Cases of Congenital Forelimb Malformations in Dogs Simona Di Pietro 1 , Giuseppe Santi Rapisarda 2, Luca Cicero 3,* , Vito Angileri 4, Simona Morabito 5, Giovanni Cassata 3 and Francesco Macrì 1 1 Department of Veterinary Sciences, University of Messina, Viale Palatucci, 98168 Messina, Italy; [email protected] (S.D.P.); [email protected] (F.M.) 2 Department of Veterinary Prevention, Provincial Health Authority of Catania, 95030 Gravina di Catania, Italy; [email protected] 3 Institute Zooprofilattico Sperimentale of Sicily, Via G. Marinuzzi, 3, 90129 Palermo, Italy; [email protected] 4 Veterinary Practitioner, 91025 Marsala, Italy; [email protected] 5 Ospedale Veterinario I Portoni Rossi, Via Roma, 57/a, 40069 Zola Predosa (BO), Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Simple Summary: Congenital limb defects are sporadically encountered in dogs during normal clinical practice. Literature concerning their diagnosis and management in canine species is poor. Sometimes, the diagnosis and description of congenital limb abnormalities are complicated by the concurrent presence of different malformations in the same limb and the lack of widely accepted classification schemes. In order to improve the knowledge about congenital limb anomalies in dogs, this report describes the clinical and radiographic findings in four dogs affected by unusual congenital forelimb defects, underlying also the importance of reviewing current terminology. Citation: Di Pietro, S.; Rapisarda, G.S.; Cicero, L.; Angileri, V.; Morabito, Abstract: Four dogs were presented with thoracic limb deformity. After clinical and radiographic S.; Cassata, G.; Macrì, F. Four Unusual examinations, a diagnosis of congenital malformations was performed for each of them. -

Identifying the Misshapen Head: Craniosynostosis and Related Disorders Mark S

CLINICAL REPORT Guidance for the Clinician in Rendering Pediatric Care Identifying the Misshapen Head: Craniosynostosis and Related Disorders Mark S. Dias, MD, FAAP, FAANS,a Thomas Samson, MD, FAAP,b Elias B. Rizk, MD, FAAP, FAANS,a Lance S. Governale, MD, FAAP, FAANS,c Joan T. Richtsmeier, PhD,d SECTION ON NEUROLOGIC SURGERY, SECTION ON PLASTIC AND RECONSTRUCTIVE SURGERY Pediatric care providers, pediatricians, pediatric subspecialty physicians, and abstract other health care providers should be able to recognize children with abnormal head shapes that occur as a result of both synostotic and aSection of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Department of Neurosurgery and deformational processes. The purpose of this clinical report is to review the bDivision of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, College of characteristic head shape changes, as well as secondary craniofacial Medicine and dDepartment of Anthropology, College of the Liberal Arts characteristics, that occur in the setting of the various primary and Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, Pennsylvania State University, State College, Pennsylvania; and cLillian S. Wells Department of craniosynostoses and deformations. As an introduction, the physiology and Neurosurgery, College of Medicine, University of Florida, Gainesville, genetics of skull growth as well as the pathophysiology underlying Florida craniosynostosis are reviewed. This is followed by a description of each type of Clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefit from primary craniosynostosis (metopic, unicoronal, bicoronal, sagittal, lambdoid, expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external reviewers. However, clinical reports from the American Academy of and frontosphenoidal) and their resultant head shape changes, with an Pediatrics may not reflect the views of the liaisons or the emphasis on differentiating conditions that require surgical correction from organizations or government agencies that they represent. -

A Heads up on Craniosynostosis

Volume 1, Issue 1 A HEADS UP ON CRANIOSYNOSTOSIS Andrew Reisner, M.D., William R. Boydston, M.D., Ph.D., Barun Brahma, M.D., Joshua Chern, M.D., Ph.D., David Wrubel, M.D. Craniosynostosis, an early closure of the growth plates of the skull, results in a skull deformity and may result in neurologic compromise. Craniosynostosis is surprisingly common, occurring in one in 2,100 children. It may occur as an isolated abnormality, as a part of a syndrome or secondary to a systemic disorder. Typically, premature closure of a suture results in a characteristic cranial deformity easily recognized by a trained observer. it is usually the misshapen head that brings the child to receive medical attention and mandates treatment. This issue of Neuro Update will present the diagnostic features of the common types of craniosynostosis to facilitate recognition by the primary care provider. The distinguishing features of other conditions commonly confused with craniosynostosis, such as plagiocephaly, benign subdural hygromas of infancy and microcephaly, will be discussed. Treatment options for craniosynostosis will be reserved for a later issue of Neuro Update. Types of Craniosynostosis Sagittal synostosis The sagittal suture runs from the anterior to the posterior fontanella (Figure 1). Like the other sutures, it allows the cranial bones to overlap during birth, facilitating delivery. Subsequently, this suture is the separation between the parietal bones, allowing lateral growth of the midportion of the skull. Early closure of the sagittal suture restricts lateral growth and creates a head that is narrow from ear to ear. However, a single suture synostosis causes deformity of the entire calvarium. -

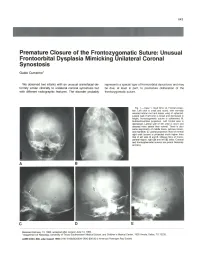

Premature Closure of the Frontozygomatic Suture: Unusual Frontoorbital Dysplasia Mimicking Unilateral Coronal Synostosis

643 Premature Closure of the Frontozygomatic Suture: Unusual Frontoorbital Dysplasia Mimicking Unilateral Coronal Synostosis Guido Currarino 1 We observed two infants with an unusual craniofacial de represents a special type of frontoorbital dysostosis and may formity similar clinically to unilateral coronal synostosis but be due, at least in part, to premature obliteration of the with different radiographic features. The disorder probably frontozygomatic suture. Fig. 1.-Case 1. Skull film s. A, Frontal projec tion. Left orbit is small and round , with normally oriented orbital roof and lesser wing of sphenoid . Lateral wall of left orbit is broad and decreased in height; frontozygomatic suture is obliterated. B, Submentovertical projection. Left frontal area is depressed. Lateral wall of left orbit is short and directed more lateral than normal. There is also some asymmetry of middle fos sa, petrous bones, and mandible. C, Lateral projection. Roof of normal right orbit (arrow) is projected much higher than that of left side. 0 and E, Oblique films of fronto parietal region, right (0) and left (E) sides. Coronal and frontosphenoidal sutures are patent bilaterally (arrows). A B c D E Received February 13, 1984; accepted after revision June 13, 1984. 1 Department of Radiology, University of Texas Southwestern Medical School, and Children's Medical Center, 1935 Amelia, Dallas, TX 75235. AJNR 6:643-646, July/August 1985 0195-6108/85/0604-0643 $00.00 © American Roentgen Ray Society 644 CURRARINO AJNR :6, July/August 1985 A B c Fig . 2.-Case 2. Skull film s. A, Frontal projection. Left orbit is small and pressed. Lateral wall of left orbit is short and directed more laterad than right. -

EUROCAT Syndrome Guide

JRC - Central Registry european surveillance of congenital anomalies EUROCAT Syndrome Guide Definition and Coding of Syndromes Version July 2017 Revised in 2016 by Ingeborg Barisic, approved by the Coding & Classification Committee in 2017: Ester Garne, Diana Wellesley, David Tucker, Jorieke Bergman and Ingeborg Barisic Revised 2008 by Ingeborg Barisic, Helen Dolk and Ester Garne and discussed and approved by the Coding & Classification Committee 2008: Elisa Calzolari, Diana Wellesley, David Tucker, Ingeborg Barisic, Ester Garne The list of syndromes contained in the previous EUROCAT “Guide to the Coding of Eponyms and Syndromes” (Josephine Weatherall, 1979) was revised by Ingeborg Barisic, Helen Dolk, Ester Garne, Claude Stoll and Diana Wellesley at a meeting in London in November 2003. Approved by the members EUROCAT Coding & Classification Committee 2004: Ingeborg Barisic, Elisa Calzolari, Ester Garne, Annukka Ritvanen, Claude Stoll, Diana Wellesley 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction and Definitions 6 Coding Notes and Explanation of Guide 10 List of conditions to be coded in the syndrome field 13 List of conditions which should not be coded as syndromes 14 Syndromes – monogenic or unknown etiology Aarskog syndrome 18 Acrocephalopolysyndactyly (all types) 19 Alagille syndrome 20 Alport syndrome 21 Angelman syndrome 22 Aniridia-Wilms tumor syndrome, WAGR 23 Apert syndrome 24 Bardet-Biedl syndrome 25 Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (EMG syndrome) 26 Blepharophimosis-ptosis syndrome 28 Branchiootorenal syndrome (Melnick-Fraser syndrome) 29 CHARGE -

Craniosynostosis (Sometimes Called Craniostenosis) Is a Disorder in Which There Is Early Fusion of the Sutures of the Skull in Childhood

Craniosynostosis (sometimes called craniostenosis) is a disorder in which there is early fusion of the sutures of the skull in childhood. It produces an abnormally shaped head and, at times, appearance of the face. The deformity varies significantly depending on the suture or sutures involved. Surgical correction may be necessary to improve appearance and provide space for the growing brain. Anatomy • The bones of the skull are the frontal, parietal, temporal, occipital, and sphenoid bones (Figure 1) • The place where two bones come together is called a suture • At birth the adjacent bones override each other to allow the infant to pass through the birth canal. hinges called sutures, which allow the head to pass through the birth canal As the child grows the sutures allow for skull expansion to accommodate the growing brain. • The brain doubles in size by age 6 months and again at age 2 years. These sutures normally begin to fuse around 2 years of age along with the closure of the fontanel (soft spot) • The seam where two skull bones fuse together is called a suture. The major sutures are called sagittal, coronal, metopic and lambdoid (Figure 2) • The sutures are completely fused by 6-8 yrs of age • Within the skull lie: 1. Brain 2. Meninges o The dura is a membrane that lines the inside of the skull o The pia-arachnoid is a filmy membrane that covers the brain 3. Blood vessels of the brain 4. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), a watery fluid that is produced by and bathes the brain Figure 1 - Anatomy of the skull in an infant Figure 2 - Infant skull showing the position showing the various bones that fuse of the major sutures. -

Craniosynostosis

European Journal of Human Genetics (2011) 19, 369–376 & 2011 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1018-4813/11 www.nature.com/ejhg PRACTICAL GENETICS In association with Craniosynostosis Craniosynostosis, defined as the premature fusion of the cranial sutures, presents many challenges in classification and treatment. At least 20% of cases are caused by specific single gene mutations or chromosome abnormalities. This article maps out approaches to clinical assessment of a child presenting with an unusual head shape, and illustrates how genetic analysis can contribute to diagnosis and management. In brief Apart from the genetic implications, it is important to recog- nise cases with a genetic cause because they are more likely to Craniosynostosis is best managed in a multispecialty tertiary be associated with multiple suture synostosis and extracranial referral unit. complications. Single suture synostosis affects the sagittal suture most com- Genes most commonly mutated in craniosynostosis are monly, followed by the coronal, metopic and lambdoid sutures. FGFR2, FGFR3, TWIST1 and EFNB1. Both environmental factors (especially intrauterine fetal head As well as being associated with syndromes, some clinically constraint) and genes (single gene mutations, chromosome non-syndromic synostosis (usually affecting the coronal abnormalities and polygenic background) predispose to cra- suture) can be caused by single gene mutations, particularly niosynostosis. the Pro250Arg mutation in FGFR3. Most genetically determined craniosynostosis is characterised In severe cases, initial care should be directed towards main- by autosomal dominant inheritance, but around half of cases tenance of the airway, support of feeding, eye protection and are accounted for by new mutations. treatment of raised intracranial pressure.